Kyiv

Kyiv [Київ; Kyjiv; Russian: Киев; Kiev]. See Google Map; see EU map: III-11. The historic and current political, religious, scientific, and cultural capital of Ukraine. It is also the capital of Kyiv oblast, the largest city (2020 pop 2,963,199) in Ukraine (with a metropolitan area of 847.66 sq km), one of the largest industrial centers, financial center, and an important transport and communications hub.

Location. Kyiv is situated on the banks of the main river of Ukraine—the Dnipro River. For over a millennium it has been the primary marketplace for the agricultural and forest products of the Dnipro Upland, Polisia, and the Dnipro Lowland. In the Middle Ages, however, far more significant was Kyiv’s location at the intersection of international trade routes: the Varangian route down the Dnipro and its tributaries to Constantinople; the overland Zaloznyi route to the Sea of Azov and Caucasia; the overland Solianyi route to the Crimea; and the overland route to Galicia, Volhynia, Transcarpathia, and the rest of Europe. Consequently, by the 11th century, Kyiv was the largest economic and political center in eastern Europe. Its proximity to the Eurasian steppe, however, also rendered it vulnerable to the invasions of Asiatic hordes, which brought about its decline.

The oldest part of Kyiv lies along the high right bank of the Dnipro River and its adjacent lower terrace among the picturesque hills between the Dnipro and the valley of its right-bank tributary, the Lybid River. The highest points in the city are 200 m above sea level, 110 m above the Dnipro’s surface; many of them rise steeply from the river, which is contained now by an embankment. The upper city was divided by the Khreshchatyi ravine; to the northwest was Old Kyiv (Starokyivska Hora) and the newer city to its west; to the southeast was the settlement of Pechersk. The main street of Kyiv—Khreshchatyk—runs along this ravine. The plateau on which the old city stands gradually drops towards the west and southwest into the wide Lybid River Valley, which was built up only in the second half of the 19th century. On the other side of the valley, hills (up to 100 m high) again rise; there the settlements of Batyiova Hora, Solomianka, Chokolivka, Sovky, and Holosiieve arose. In the southwest periphery of the city the hills give way to relatively flat rolling land.

The most western and northwestern parts of Kyiv (Sviatoshyno, Pushcha-Vodytsia) lie on a sandy plain amid pine forests. Northeastern Kyiv is situated on a plain of the Dnipro Lowland and consists of a lower floodplain-meadow terrace and an upper wooded terrace with sandy soil and remnants of pine forests. On the Dnipro’s right bank this plain covers only a small area; on its southern part lies Podil, the old lower district closest to the river, while farther north lie Kurenivka and Priorka. On the left bank, both terraces cover a larger area; there, at some distance from the water, lies the new Darnytskyi city raion. The Dnipro River, along with its eastern channel, the Desenka or Chortoryi, serves as the city’s main water source and focus for recreation. The natural flora in Kyiv’s 66 parks is both coniferous (pine) and deciduous (oak and hornbeam).

History. The oldest human traces on the territory of Kyiv date from the late Paleolithic Period (see Kyrylivska archeological site). Traces of Eneolithic Trypillia culture settlements are numerous, as are those of the Bronze Age and Iron Age. Excavated hoards of Roman coins and of burial grounds of the 2nd–4th centuries AD show that Kyiv was already a large settlement and an important trading locus at that time (see Kyiv hoards).

According to the Rus’ Primary Chronicle, the founders of Kyiv were the brothers Kyi, Shchek, and Khoryv, leaders of the Slavic tribe of Polianians, and the city was named after the eldest, Kyi. According to Soviet historiography, Kyiv was founded in the latter half of the 5th, or the early 6th century, and in 1982 its 1,500th anniversary was officially celebrated.

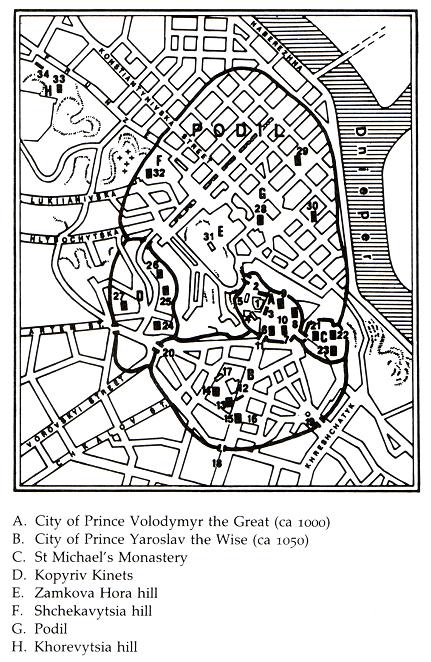

The rise of Kyiv. Kyiv was the capital city of the Polianians from the 8th century. At that time there were three distinct fortified settlements—one on Saint Andrew’s Hill, one on Kyselivka Hill, and one in the vicinity of present-day Kyrylivska Street—which were amalgamated in the 10th century. The court of the princes was located in one of these settlements. The trading district was Podil, at the mouth of the now non-existent Pochaina River, where there was a landing.

With the founding of Kyivan Rus’ in the second half of the 9th century, Kyiv became its capital.

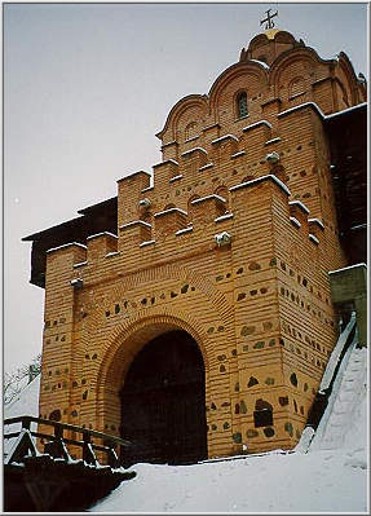

Grand Prince Volodymyr the Great (980–1015) extended the city’s boundaries, and constructed the Church of the Tithes and new, finely ornamented stone palace buildings. The houses of boyars and the royal retinue stood nearby, as did the tradesmen’s quarters and the market square (Babyn Torzhok), which was decorated with trophies. Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise (1019–54) extended the upper city onto a neighboring plateau and fortified it with a 14-m-high rampart with gates and palisades and a moat. In 1037 he built the Saint Sophia Cathedral and many other churches and secular buildings. Under Yaroslav, Kyiv became a trade and political center of international stature. The opulence of his court, the beauty and luxury of Kyiv’s buildings, and the city’s populousness (50,000–100,000 by the 12th century) are documented in contemporary foreign travelers’ accounts.

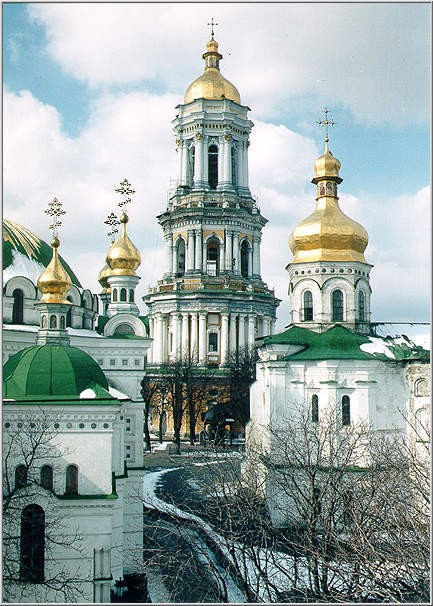

At that time Kyiv was the religious center of Eastern Europe. A metropolitan’s see (see Kyiv metropoly), it had numerous churches and monasteries (the most famous being the Kyivan Cave Monastery). It was also a center of learning, writing, book transcribing, and painting. The first Rus’ chronicles were written there (particularly at the Kyivan Cave Monastery and Vydubychi Monastery). The Saint Sophia Cathedral housed the prince’s library—the first library in Ukraine.

For centuries, the upper city (see Starokyivska Hora) was primarily the administrative, military, and cultural center, while the more populous lower city (Podil) was mainly the commercial and manufacturing district, with many shops, merchants’ quarters, and foreign enclaves. The city’s viche (popular assembly) took place in Podil. The prince’s village of Berestove, the Kyivan Cave Monastery, and, farther south, the Vydubychi Monastery stood outside the walls of the original city.

The richness and fame of Kyiv attracted many plunderers, and it sustained numerous attacks and ruin by the Pechenegs and the Cumans. With the partition of Rus’ among the various princes, Kyiv was assigned to the eldest son of the grand prince. Incessant internecine battles for the throne of Kyiv ensued. The sack of the city by Prince Andrei Bogoliubskii of Suzdal in 1169 and by Prince Riuryk (Vasylii) Rostyslavych and his allies (the princes from the Olhovych house of Chernihiv and the Cumans) in 1203 were particularly destructive.

Kyiv in decline, 13th–16th centuries. As a result of the unceasing wars and plunderings, Kyiv’s importance dwindled. In December 1240, it was sacked by the Mongol-Tatar army of Batu Khan, which decimated its population. In the second half of the 13th century, the city underwent a revival under the rule of the vassal princes of the Golden Horde. In 1362–3 Grand Duke Algirdas of Lithuania annexed the Kyiv land to his realm as an appanage principality; it was governed by Volodymyr, son of Algirdas, who built a castle above Podil, on a steep hill called Zamkova hora (Castle mountain), aka Tyselivka, Khorevytsia or Frolivska hora. Volodymyr’s descendants governed Kyiv until 1470. From 1471 to 1569 Kyiv was governed by Lithuanian viceroys. In 1471 it became the capital of Kyiv voivodeship. In the early 15th century, Kyiv’s trade and crafts revived to the extent that the burghers of Podil were granted self-government by Grand Duke Vytautas the Great, and between 1494 and 1497 the entire city received the rights of Magdeburg law.

Kyiv suffered greatly from Tatar depredations in the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1482, the Crimean khan Mengli-Girei, an ally of the Muscovite grand prince Ivan III, plundered Kyiv and sent a golden chalice and dyskos taken from the Saint Sophia Cathedral to Moscow. The upper city lay in ruin for over a hundred years, during which time Podil was the center of activity. Above Podil, the castle of the Lithuanian voivode was re-built in 1510. In 1569, in keeping with the provisions of the Union of Lublin, Kyiv and Kyiv voivodeship came under Polish rule and cultural influence as part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

17th and 18th centuries. In the early 17th century, Kyiv underwent a renaissance, becoming the political, religious, and cultural center of Ukraine. The Cossack hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny (ca 1610–22) resided there and belonged to the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood. In 1615 the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School was founded in Podil and the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press was established. In 1620 Patriarch Theophanes III of Jerusalem restored the Ukrainian Orthodox church hierarchy and Kyiv metropoly (after the 1596 Church Union of Berestia, Kyiv had been the see of only the Uniate metropolitan). As the archimandrite of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1627–32) and the metropolitan of Kyiv (1632–47), Petro Mohyla did much to make Kyiv an important cultural center. The school he founded at the monastery in 1631 was amalgamated with the brotherhood school in 1633 to form the famous Kyivan Mohyla College (renamed the Kyivan Mohyla Academy in 1701). He initiated and funded the restoration of many of Kyiv’s old churches (particularly the Saint Sophia Cathedral) and the erection of many new ones.

During the Cossack-Polish War, Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and his army triumphantly entered Kyiv in December 1648 to the joyful welcome of the populace. His army cleared the city of Polish forces in 1648, and Kyiv became the capital of Kyiv regiment. In 1651, however, Kyiv was ravaged by the Polish-Lithuanian army. After the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654, a Muscovite garrison was stationed in Kyiv, and a Muscovite fortress was built in the upper city. The Muscovite-Polish Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) granted Kyiv to Muscovy for two years, but the Muscovites managed to retain it permanently and had their control formalized in the Eternal Peace of 1686. Thenceforth until 1793, Kyiv was an autonomous border town linked to the Muscovite-Russian state, the rest of Right-Bank Ukraine remaining under Poland.

Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687–1709) contributed much to Kyiv’s cultural and architectural development. After his defeat by Peter I at the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Kyiv’s economic and religious importance was severely undermined by tsarist policies. The Russian monarchs, particularly Peter, Anna Ivanovna (1730–40), and Catherine II (1762–96), progressively eliminated Kyiv’s municipal autonomy, appointing their own functionaries to traditionally elective posts such as that of mayor (viit). Trading restrictions were imposed on Ukrainian merchants, while Russian merchants and artisans received preferential treatment and began settling in the city in increasing numbers. City-owned taverns (an important source of municipal revenue) were replaced by state-run ones. Outsiders and foreigners were allowed to reside in the city, changing its composition. In 1786 monastic properties were secularized.

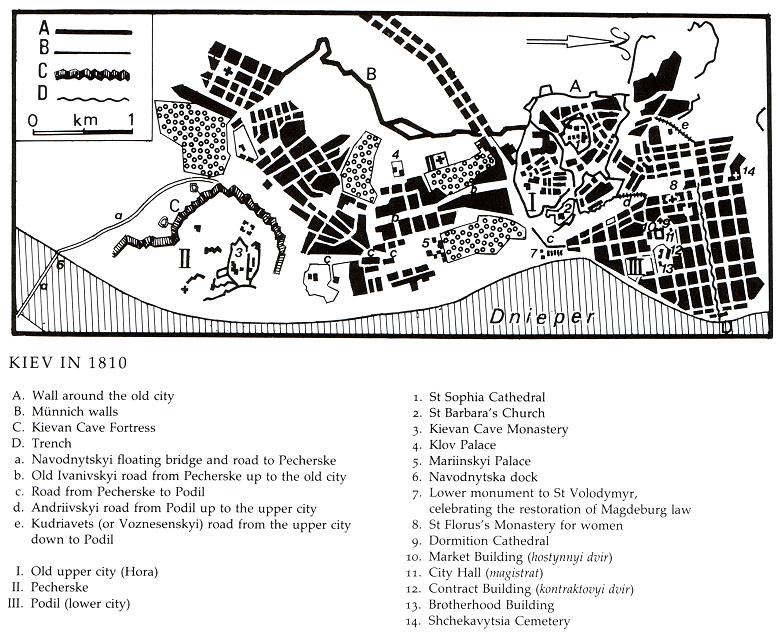

In the late 18th century, Kyiv still consisted of three separate, fortified, and built-up settlements: Podil, which had its own town council (magistrat); the fortified upper (old) city, where the metropolitan resided; and Pechersk, around the Kyivan Cave Monastery and the Kyivan Cave Fortress (completed in 1723), where the Russian military and civil authorities were based from 1711. In 1782 Catherine II abolished the regimental system of the Cossack Hetman state, and Kyiv became the capital of Kyiv vicegerency encompassing Left-Bank Ukraine lands of Kyiv regiment, Pereiaslav regiment, Lubny regiment, and Myrhorod regiment. After the second partition of Poland in 1793, Russia annexed much of Right-Bank Ukraine. In 1796 Kyiv vicegerency was abolished, and Kyiv became the capital of Kyiv gubernia in 1797.

The 19th and early 20th centuries. As the capital of Kyiv gubernia, Kyiv became the capital of Right-Bank Ukraine (the ‘Southwest Region’). It attracted new residents, many of them Poles from the Right Bank, and its population rose steadily, from 30,000 in the late 18th century to 45,000 in 1840, despite cholera epidemics and a high mortality rate. Urban reconstruction, planning, and development began in earnest, particularly in Podil, after the great fire of 1811. The Kyivan Cave Fortress was renovated and much enlarged in 1831–61. Residents displaced by this construction moved to the newly developed districts in the Lybid River Valley and Khreschatyi ravine—upper-class Lypky, lower-class Shuliavka, and others. Old roads were repaired and new ones were built (eg, Khreshchatyk, Volodymyrska Street, and Bibikov [now Taras Shevchenko] Boulevard) in the 1830s and 1840s. The government and private individuals constructed new stone residences, churches (eg, one at Askoldova Mohyla, 1810; the Church of the Nativity in Podil, 1812), and public buildings (eg, the Kyiv Contract Fair Building in Podil [1801] and Kyiv University [1837–43]) in the classicist style. The slopes of the hills along the Dnipro River were reinforced, and the first suspension bridge spanning the river was built in 1848–53 (destroyed in 1920). As a result of all this development, the once separate districts began merging, and the suburbs began growing.

In the 1830s and 1840s, after the suppression of the Polish Insurrection of 1830–1, intensive government-directed Russification of the city and of Right-Bank Ukraine occurred in an attempt to destroy the power of the Poles there; Ukrainians and their traditions were greatly affected by this process. In 1835 Kyiv’s rights of Magdeburg law was officially rescinded. The city duma (a council based on the Russian model), which replaced the magistrat in administrative matters in 1785 and in judicial matters in 1835, became dominated by Russian merchants. Russians were encouraged to settle in Kyiv by the imperial government, which offered them tax exemptions and other economic incentives to do so, and their weight in the city’s population rose swiftly. To promote Russification, the tsarist regime concentrated on education. It brought in Russian teachers and opened Saint Vladimir University (now Kyiv National University) and a second gymnasium (the first was opened in 1809) in 1834, an institute for daughters of the nobility in 1838, and a military cadet school in 1852. Russification of religion was fostered at the Kyiv Theological Academy, which replaced the Kyivan Mohyla Academy in 1819. In 1838, the regime began publishing the Russian newspaper Kievskie gubernskie vedomosti (three issues per week).

Despite Russification and repression, a Ukrainian national movement arose in Kyiv. The secret Society of United Slavs (1823–5) and the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood (1845–7) were based there, and the Ukrainian scholar Mykhailo Maksymovych was the first rector of Kyiv University. In the late 1850s and 1860s, the khlopoman movement had a number of adherents among the Kyiv University students and other members of the intelligentsia, as did the Kharkiv-Kyiv Secret Society. The Ukrainophile student society, which later became the famous Hromada of Kyiv in 1859, had among its members many figures who came to play leading roles in Ukrainian life. In the years 1859–62, Kyiv’s Ukrainian intelligentsia organized the first Sunday schools in the Russian Empire. In 1870, Galagan College was founded; many of its teachers were Ukrainophiles. Kyiv became the center of revolutionary populism in Russian-ruled Ukraine; active there were such revolutionary groups as the Kyiv Commune (1873–4), the South Russian Workers' Union (1880–1), and Narodnaia Volia (1884).

Kyiv grew rapidly in the second half of the 19th century as a result of the general economic development of Russian-ruled Ukraine and the building of the first railway line, which connected it with Odesa and Moscow in 1869–70. The most important economic sector in Kyiv continued to be trade, 50 percent of which was in beet sugar; Kyiv was the main market of the sugar industry in the Russian Empire. The other 50 percent of Kyiv’s trade was in grain, machinery, and manufactured goods, which were sold at the Kyiv Contract Fair, at five smaller annual fairs, and at 1,060 (in the 1860s) trading houses. Kyiv’s commercial-financial center shifted from Podil to Khreshchatyk. Industry was of secondary importance in Kyiv’s economy: it consisted mainly of food processing (62 percent of all production), distilling, tanning, metalworking, machine building (for the food-processing industry and water and railway transport), brickmaking, printing, and footwear and clothing manufacturing. Kyiv’s factories were relatively primitive and small; in 1900 there were 121, employing a total of 11,230 workers. In 1912, there were 14,600 industrial workers and 30,000 artisans and cottage-industry workers. As an industrial center, Kyiv lagged behind such cities as Kharkiv, Katerynoslav, and Odesa, mainly because of its distance from the nearest sources of fuel (coal) and raw materials (iron ore).

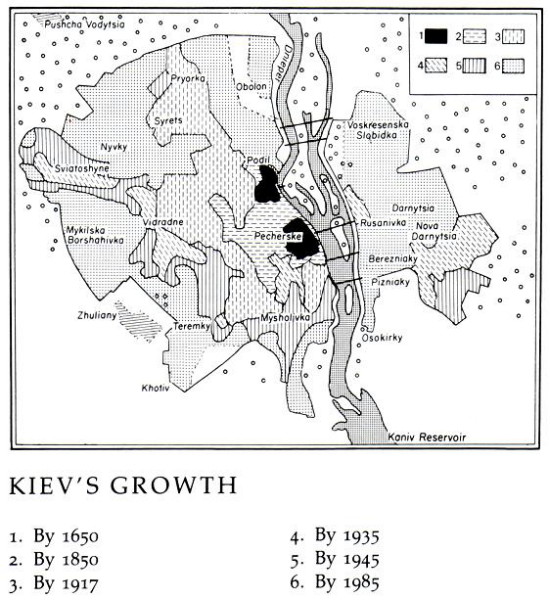

Because it was an important administrative center, however, Kyiv’s population multiplied: from 65,000 in 1861 to over 127,000 in 1874 and 248,000 in 1897. Its various districts and main streets were increasingly built up. The city expanded mainly westward, absorbing adjacent villages and locales (Lukianivka, Shuliavka, Protasiv Ravine); at the turn of the 20th century it had an area of 18,000 ha. Limited public utilities were established in the central part of the city: a telegraph (1854), street gaslights (1872), a river water-supply system (1872), city hospital (1874), telephone system (ca 1886), electricity (1890), horse-drawn streetcars (1891), an electric tramway (1892, the first in the Russian Empire and the second in Europe), sewage system (1894), artesian water-supply system (1896), and new river port (1900). Poor sanitation, water shortages, cholera, urban poverty, and substandard housing, however, remained major problems, and labor conflict (over low wages, long hours, and unsafe conditions) was a common occurrence from the mid-1890s.

Many new buildings were erected in the 1890s and 1900s: banks, schools, libraries, a city museum (1899) (now National Museum of the History of Ukraine), theaters, an opera house, two People's homes (1897, 1902), a public auditorium (1895), hospitals, hotels, and a covered market. Their architecture was, in most cases, an eclectic combination of styles, ranging from Renaissance to Art Nouveau and Modern. At the turn of the century, Kyiv was considered to be in the vanguard of the Russian Empire’s cities in terms of communal planning. Only its core districts, however, were well planned: in 1912, there were still more wooden (11,500) than stone (5,500) buildings; two-thirds of all homes were one- or two-story; and electric power, water supply, sewers, and paved roads existed only in the city’s central area.

Russification did not diminish in the latter half of the 19th century. It was even intensified after the Polish Insurrection of 1863–4. The use of Polish was forbidden, and the government established a network of elementary schools, many secondary chools for boys and girls, and several Russian libraries and professional cultural-educational societies; it also subsidized a new newspaper, Kievlianin (1864–1919). In an attempt to counteract official Russification, in 1873 members of the Hromada of Kyiv created the Southwestern Branch of the Imperial Russian Geographic Society, and in 1874 the Hromada turned the newspaper Kievskii telegraf into its semiofficial organ.

In 1875–6, the imperial government forbade all Ukrainophile activities and outlawed the Ukrainian language (see Ems Ukase), forcing the Ukrainian movement underground. Thenceforth until the 1900s, a number of illegal, mostly student, political and educational organizations existed in Kyiv; influenced mainly by the writings of Mykhailo Drahomanov, an entire generation of Ukrainian activists matured within their ranks. The only legal Ukrainian-content periodical in Kyiv in this period was the Russian-language Kievskaia starina (1882–1906), which was founded by the Hromada of Kyiv. From 1893 to 1898 Kyiv was the center of the Brotherhood of Taras, cofounded by Borys Hrinchenko. In 1897, members of the Hromada of Kyiv founded the clandestine General Ukrainian Non-Party Democratic Organization. The first Ukrainian revolutionary parties were established in Kyiv: the Revolutionary Ukrainian party (1900), the Ukrainian Socialist party (Kyiv) (1900), the Ukrainian People's party (1902), the Ukrainian Democratic party (1904), the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers' party (1905), the Ukrainian Democratic Radical party (1905), the Ukrainian Social Democratic Spilka (1905), and the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (1905).

During the liberal period after the Revolution of 1905, Kyiv was the focal point of Ukrainian cultural, scholarly, publishing, and political activity. Various periodicals were published: the daily Hromads’ka dumka (1906) and Rada (Kyiv) (1906–14); the weekly Slovo (Kyiv) (1907–9), Ridnyi krai (1908–14), Selo (1909–11), Zasiv (1911–12), Muraveinyk-Komashnia (1912–19), and Maiak (Kyiv) (1912–14); the semimonthlies Rillia (1911–18) and Nasha kooperatsiia (1913–14); and the monthlies Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk (1907–14, 1917–19), Ukraïns’ka khata (1909–14), Svitlo (Kyiv) (1910–14), Dzvin (Kyiv) (1913–14), and Siaivo (1913–14). In 1906, a Prosvita society was founded; in 1907 the Ukrainian Scientific Society and the first permanent Ukrainian professional theater, Sadovsky's Theater; and in 1908, the clandestine Society of Ukrainian Progressives. Over 10 Ukrainian publishing houses were founded, numerous Ukrainian art exhibits were held, the literary-cultural Ukrainian Club was opened in 1908, and a committee to erect a monument to Taras Shevchenko was struck. The Lysenko Music and Drama School (est 1904) became the main center of music education.

The forces of Russian reaction (eg, the Black Hundreds and the Kyiv Club of Russian Nationalists) tried to undermine and suppress this multifarious activity (a notable example was the official banning of celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s birth), but only after the outbreak of the First World War were most Ukrainian organizations and institutions closed down by the authorities. On the eve of the war, Kyiv’s population was 626,000, almost 10 times greater than it was in 1861 (65,000). In area it was the third-largest city in the Russian Empire.

Kyiv as the capital of the independent Ukrainian state, 1917–20. After the February Revolution of 1917, Kyiv became the center of the Ukrainian national revival, led by the Ukrainian Central Rada. The newspaper Rada (Kyiv) was revived as Nova rada (Kyiv). A Provisional Ukrainian Military Council and various clubs (eg, Soldiers’, Railway Workers’) were established. On 1 April 1917, a massive Ukrainian national demonstration (estimated at 100,000 participants) took place. Several All-Ukrainian congresses followed; the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Church Council was established; and education, art education, and theater arts education in Ukrainian and the Ukrainian co-operative movement flourished. The General Secretariat of the Central Rada was based in Kyiv, and the formation of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) (20 November 1917) and its independence (25 January 1918 [predated to 22 January]) were both proclaimed there.

From 29 January to 8 February 1918, a Bolshevik Arsenal uprising took place in Kyiv; Soviet rule and terror lasted there until 2 March, when the UNR Army and German troops regained the city. On 29 April a military coup took place in Kyiv, and until 14 December 1918 Kyiv was the capital of the conservative Hetman government of Pavlo Skoropadsky, which founded the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, the National Library (now the National Library of Ukraine), the State Drama Theater, the State People's Theater, and other institutions there. On 14 December the anti-Hetman forces of the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic took Kyiv, and on 22 January 1919 the union of the Ukrainian National Republic and the Western Ukrainian National Republic was proclaimed there. On 5 February 1919, Bolshevik forces once again seized Kyiv, and a Cheka reign of terror ensued. On 30 August, combined forces of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic and Ukrainian Galician Army forced the Bosheviks to abandon Kyiv, but they were themselves forced to withdraw by the advancing Russian Volunteer Army of General Anton Denikin. On 16 December, the Bolsheviks again took Kyiv. They were expelled on 6 May 1920 by a joint UNR-Polish offensive, but on 12 June they reoccupied the city.

The years of Ukrainian struggle for independence (1917–20), the Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917–21, and the frequent battles for control of Kyiv caused much destruction and suffering to the city’s residents, and many of them fled from the hunger and terror. As a result of wartime deaths and this exodus, Kyiv’s population fell from 544,000 (1919) to 366,000 (1920).

The interwar years. Although Kyiv was rebuilt, its importance was diminished after Kharkiv became the capital of Soviet Ukraine in 1920. Kyiv was neglected, and its economy and population (which reached 513,600 in 1926) grew at a slower pace than in the new capital and the cities of the industrial regions. Kyiv remained, however, the focal point of Ukrainian scholarly life because the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences (VUAN) and numerous institutions of higher education were established there. It also remained the main center of Ukrainian religious life, particularly of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church, which was established there in 1920. Kyiv was also an important center of the literary and cultural renaissance that accompanied the policy of Ukrainization in the 1920s. The Neoclassicists and the writers' group Lanka-MARS were based there, and the important cultural journal Zhyttia i revoliutsiia (1925–34) was published there. The famous Berezil theater was founded in Kyiv in 1922 and remained there until 1926, and the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration was relocated to Kyiv in 1928.

By the late 1920s, however, Kyiv’s intelligentsia was subjected to the first onslaught of Stalinist repressions and terror: the arrests and show trials of the alleged members of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU) (1929–30). Ukrainization was abandoned in the early 1930s, and Russification of the Party and government apparats and of all educational institutions intensified. In most post-secondary schools and professional schools, instruction in Ukrainian virtually disappeared, and by the mid-1930s Ukrainian was rarely spoken in public.

In 1934, the Soviet regime decided to move the capital back to Kyiv, ‘the natural geographic center’ of Ukraine, and began a program of intensive industrialization of the city. Consequently Kyiv boomed, and its population grew from 578,000 in 1930 to 930,000 in 1940, much of it fed by peasants fleeing from the impoverished countryside. This transformation and growth necessitated the construction of new public and residential buildings. Much of Kyiv’s formerly undeveloped land was used for this purpose, and the city expanded east across the Dnipro River, incorporating Darnytsia. In 1934–6, while the buildings and squares of the new government center were being designed, over two-dozen churches and other landmarks were senselessly destroyed in the old city, including Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, the Church of the Tithes, and the Church of the Three Saints. Iconostases were removed from many churches, including the churches of Saint George and Saint Michael at the Vydubychi Monastery. Landmarks were also destroyed in Podil (the Pyrohoshcha Church of the Mother of God, Saint Flor's Monastery, and the Epiphany Church of the former Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood Monastery), in Pechersk (Saint Nicholas's Military Cathedral), and in other parts of Kyiv (Saint Cyril's Monastery); singled out for destruction were the churches whose construction had been funded by Hetman Ivan Mazepa. Several historic cemeteries, where many eminent Kyivans were buried, were desecrated and paved or turned into parkland. Nevertheless, public utilities and the railway and public-transit networks in and around Kyiv were improved; a second railway bridge (1929) and a new suspension bridge spanning the Dnipro (1925), a large new train station in the constructivist style (1932), a second airport (1933, in Brovary), a 150-kW radio station (1936), an automatic telephone exchange (1935), and a new thermal-power station (1936) were built.

The Second World War. After Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941, most of Kyiv’s intelligentsia and over 300,000 of its inhabitants were evacuated and 197 factories were dismantled and shipped to Soviet Asia. Before their final withdrawal, the Bolsheviks mined many public and residential buildings and destroyed the three bridges spanning the Dnipro River, the railway station, and all railway shops, power stations, waterworks, and food and fuel depots. The Germans occupied Kyiv on 19 September. Soviet mines began detonating on the 20th, and a huge fire raged for 10 days, destroying the buildings on Khreshchatyk and many adjacent streets. On 3 November a Soviet mine destroyed the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery.

Under the Germans, limited Ukrainian nationalist activity was briefly tolerated. A writers’ and artists’ associations were organized, and some publishing was allowed (eg, the dailies Ukraïns’ke slovo (1941) and Nove ukraïns’ke slovo [1941–3]). The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church, Ukrainian Red Cross, and Ukrainian co-operative movement were revived and a military club was founded by the new German-approved municipal administration headed by Oleksander Ohloblyn and then V. Bahazii and L. Forostivsky. In October 1941 the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists—OUN (Melnyk faction)—created a Ukrainian National Council (Kyiv), headed by Mykola Velychkivsky, but it was soon outlawed by the Germans, who began a campaign of forced labor, terror, and suppression throughout the country. Many OUN activists were arrested, tortured, and shot. All schools were closed down, and no organized activity was allowed.

During the German occupation of Kyiv, at least 200,000 of Kyiv’s residents, mostly Jews but also Ukrainians and Russians, were murdered (see Babyn Yar). About 100,000 Ukrainians were forcibly sent as Ostarbeiter to Germany. About 100,000 Soviet soldiers died in German prisoner of war camps in Darnytsia and Syrets. During the winter of 1941–2, the Germans forbade the importation of food to Kyiv and caused a famine there. By the summer of 1943, Kyiv’s population was only 305,000. Before the Germans withdrew from Kyiv in November 1943, they looted its museums, libraries, factories, and homes, razed the settlements on the Dnipro River’s left bank, burned Kyiv University and many other buildings, and destroyed the bridges they had rebuilt. Over 800 of Kyiv’s 1,176 enterprises, 42 percent of its living space, 940 government and public buildings, and most of its central streets lay in ruins. When the Red Army entered Kyiv on 6 November, 80 percent of its residents were homeless.

The postwar period. After the Second World War, Kyiv’s buildings, streets, public utilities, and industries were rebuilt and modernized. Kyiv’s population grew from 180,000 in 1943 to 472,000 in 1945 and 1,174,000 in 1961. New residential districts were created in the suburbs, and new industries were established. By 1949 industrial production attained the prewar level and it increased thereafter. The city’s area increased from 680 sq km in 1940 to 769 sq km in 1960. In 1946–60, 5.2 million sq m of housing was built. By 1948 the city was served by the Dashava-Kyiv gas pipeline. In 1949 construction of the Kyiv metro began; it was opened in 1960. In 1951–8 the pavilions of the permanent Exhibition of Economic Achievements of the Ukrainian SSR were built.

Since the war Kyiv has steadily expanded, annexing villages to its west, east, and north. Since 1957, and particularly in the 1970s, many large apartment complexes have been constructed in these new suburbs. Kyiv’s total housing fund rose from 6.74 million sq m in 1950 to 33.6 million sq m in 1981, 43.6 million sq m in 1990 and 54.0 million sq m in 2004. Kyiv is one of the most verdant cities in Ukraine and Europe. Its ‘green zone’ of 60 parks, suburban forested areas, and chestnut-, poplar-, and linden-lined boulevards and squares had a total area of 383,000 ha, 18,300 ha (1980) of it in the city proper. As a result of recent annexations, the forested area in the city proper has increased to 36,100 ha (2006).

Kyiv is the center of political activity in Ukraine. In the 1960s most of the writers and artists who protested Russification and Communist dictatorship lived in Kyiv. The Ukrainian Helsinki Group also was established in Kyiv in 1976.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of restructuring and democratization (perestroika) in the late 1980s allowed for the ferment in Ukraine to come into the open, manifesting itself in political changes that played out in Kyiv. These included the first ecological demonstration on the second anniversary of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster (26 April 1988); the establishment of the Society for the Ukrainian Language (Tovarystvo ukrains’koi movy, 13 June 1988); the meeting of writers that initiated the formation of Rukh or the Popular Movement of Ukraine for Restructuring (Narodnyi Rukh Ukrainy za perebudovu, 28 November 1988); the change in the leadership of the Communist Party of Ukraine in Kyiv at various levels (1989); the formation of the Taras Shevchenko Republic Association of Ukrainian Language (Respublikans’ke tovarystvo ukrains’koi movy im. Tarasa Shevchenka, February, 1989), which pressured the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR to give the Ukrainian language the status of the state language (December, 1989); the establishment of the Memorial Historical-Educational Association (Istoryko-prosvitnyts’ke tovarystvo ‘Memorial’, March 1989), which pressured the authorities to change toponyms named after leaders, who carried out massive repressions, to open the archives of the organs of repression, to return the confiscated property to the repressed or their relatives, to hallow the memory of the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3 (Holodomor), and to memorialize the executed, buried in unmarked mass graves, at the Bykivnia Forest; the organization of a conference by the Rukh council, together with the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, on the 71th anniversary of the Act of the Unification of the Ukrainian National Republic and the Western Ukrainian National Republic, and their decision to organize the so-called ‘Live Chain’—‘The Ukrainian Wave’, where residents all along the highway from Lviv to Kyiv held hands to symbolize the unity of the Ukrainian nation (21 January 1990); the victory of the democratic block in the election to the Kyiv city council followed by the symbolic raising of the until then forbidden blue-and-yellow flag over the Kyiv city hall (24 July 1990); the election of democratic candidates, including dissidents, to the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (March, 1990) and their ability to form a democratic block and influence politics and legislation after the Supreme Soviet, for the first time, began to function as a real parliament (15 May 1990).

Although the Supreme Soviet passed the Declaration on the State Sovereignty of Ukraine on 16 July 1990, the Communist majority stalled on specific measures. This prompted students to stage a hunger strike (at what is now known as the Independence Square) in support of the democratic block (October, 1990), a move that garnered public sympathy for the cause of national sovereignty. These developments prompted the re-naming of the Russian Orthodox church in Ukraine the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate and allowed for the re-emergence of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church and the Ukrainian Catholic church. The latter two churches then laid claims to church property, notably in Kyiv. Other religious groups also became more active and numerous new political organizations emerged in Kyiv.

Since 1991. Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, Kyiv expanded its role from that of an administrative center of a republic within the USSR to that of a political center of an independent country. In developing that function in the context of political-administrative reforms, it expanded the facilities for the growing responsibilities of the Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council of Ukraine or Parliament), the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the Prosecutor General and the Supreme Court of Ukraine, and acquired three new government institutions: the President of Ukraine, the National Bank of Ukraine, and the Constitutional Court of Ukraine. Moreover, it became the location of the head offices of numerous non-governmental organizations as well as many embassies and offices of international organizations, foreign-based commercial firms, and multinational corporations. This administrative and institutional growth resulted in an influx of new residents and encouraged domestic and foreign investment, which in turn spurred a building boom involving the renovation of old and the construction of new apartment and office buildings. The rebirth of independence also enabled the return to Kyiv of some émigré institutions, such as the Ukrainian nationalist organizations of both OUN (Bandera faction) and OUN (Melnyk faction), the former of which formed a political party: the Congress of the Ukrainian Nationalists.

The official status of the Ukrainian language prompted changes of street names and signs in Kyiv. Also many Soviet-era names of streets and squares were replaced with their historical counterparts (eg, the name Contract Square was again assigned to the Red Square and the name St. Michael’s Square replaced the Soviet Square) or names of important Ukrainian historical figures (eg, Andrei Zhdanov Street was renamed Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny Street, Vladimir Lenin Street became Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, and Aleksandr Kirov Street was renamed Mykhailo Hrushevsky Street), while the October Revolution Square became the Independence Square. The historical Kyivan Mohyla Academy was restored as the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in place of the Soviet Naval Academy that occupied some of its old buildings. Several of Kyiv’s major architectural landmarks, destroyed in the 20th century, were rebuilt: the Pyrohoshcha Church of the Mother of God in Podil, the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery and the cathedral of the Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery.

The collapse of Soviet command economy at the end of the 1980s depressed Kyiv’s industrial sector, but the revival of market relations stimulated the development of its commercial profile. As a result, the gross value added (GVA) of the city continued to grow, expanding from 7.4 percent of the GVA of Ukraine in 1996 to an astounding 18.0 percent in 2003. This meant that, on a per capita basis, the GVA of Kyivans in 2003 was 3.3 times higher than the average for Ukraine as a whole.

Economy. Kyiv has a diversified, dynamic and growing economy, including a variety of industries and various forms of services, from administration and finances to sales, personal services, education, entertainment and transportation.

As the capital of Ukraine, Kyiv derives its funding from both its city tax base and from the state budget; its functions as a capital are funded directly by the government of Ukraine. Given the limitations of the budgets, no effort is spared to attract foreign direct investment to the city. The attraction of the city as a capital as well as the efforts of its promoters have resulted in a high concentration of foreign direct investments in Kyiv. In 1998, 30 percent of the FDR into Ukraine went to Kyiv, 9.8 percent to Kyiv oblast, 7.7 percent to Dnipropetrovsk oblast, 6.5 percent to Cherkasy oblast, and 45 percent to the remaining 22 oblasts of Ukraine. Much of this investment has been directed at improving Kyiv’s infrastructure and in the construction of hotels, office buildings and residences.

The revival of the economy in 1997 stimulated the city’s construction industry. Residential blocks continued to be built in keeping with the plans created by the leading design institution of Ukraine, Kyivproekt (formerly a government agency, now a joint-stock company). Although in 1998 organizations and enterprises subordinated to the city council completed the construction of apartment buildings with 350,300 sq m of living space, and other enterprises, subordinated to other government ministries, contributed another 207,000 sq m, the private sector contributed even more. The Kyivmiskbud holding company built 44 buildings with 383,500 sq m, while other private efforts resulted in another 34 buildings with 295,100 sq m.

Kyiv is the financial center of Ukraine. It houses the national financial policy making bodies of the government, including the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, the National Bank of Ukraine, and the State Treasury of Ukraine. It was here that, following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, decisions were made to exit from the ‘ruble zone’ (1991), introduce the temporary ‘coupon-karbovanets’ during hyper-inflation (1992), create the Ukrainian Inter-Bank Currency Exchange (1993), and the new currency hryvnia when inflation was brought under control (1996). It was here that legislation was passed (1993) and confirmed in the Constitution of Ukraine (1996) regarding the functions of the National Bank of Ukraine and its relations to the commercial banks that emerged in Ukraine in place of state banking institutions. In 1996 there were more than 200 commercial banks, of which 93 joined the Association of Ukrainian Banks (1997). Most of them established either their head offices or branches in Kyiv. By 1998 80 banks were represented in Kyiv, of which 6 were foreign-based. In addition, there were 200 companies in Kyiv involved in the privatization of state assets, and 80 insurance companies. The National Association of Exchanges was established in Kyiv in 1996 to facilitate the functioning of trade in agricultural, industrial and other traded commodities and to oversee the legality of trading at various exchanges. Kyiv has gained the offices of a number of international financial organizations, including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank.

Since the 1930s the main economic sector in Kyiv has been industry. After the consolidation of Soviet rule, it reached its pre-First World War level in 1925–6 and was significantly strengthened and modernized during the first two Five-year plans in the 1930s and again after the Second World War, particularly in the areas of machine building and light industry. Kyiv’s industry has grown thirtyfold in the period from the Second World War to the late 1980s. The main changes in output are shown in table 1. The importance of Kyiv's machine building and metal working industries grew even more between 1978 and 1983 (see table 2). Since the economic decline at the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s, industry in Kyiv also declined, bottoming out in 1996 at 52 percent of its output in 1990, but recovering to 97 percent of the 1990 output in 2000 and attaining 168 percent of the 1990 output (by value) in 2004. In 2000 Kyiv had more than 400 large industrial enterprises and several thousand medium and small enterprises. These industrial enterprises employed 15.3 percent of the work force of Kyiv.

The percentage composition of the industries in Kyiv, by value of production in 2000, is shown in table 3, and can be compared to previous years in table 1 and table 2. Besides the main industrial branches listed in tables 1 and 2, and the longer list in table 3, other industries that are important in Kyiv’s economy include the medical-technology, pharmaceutical, and printing industries.

During the decline (1989 to 1996), the machine building and metalworking sector, which was to a large extent connected to the industrial-military complex and depended on state orders in the former command economy, was most negatively affected. The consumer goods and food processing industries, being more closely related to the consumer demand, fared less badly during the decline. In fact, the food industry, in particular, gained in share. Even so, the internationalization of the consumer goods market had a powerful impact on the consumer goods industries of Ukraine, particularly the light industry, which was undercut by cheap imports from Asia.

Electric power is an essential attribute of the urban economy. The city is powered by two central thermoelectric stations (one of them, the TETs-5 [completed in 1971], was one of the largest in the USSR), the Kyiv Hydroelectric Accumulation Station (HAES, completed in 1970, 37,500 kW), the Kyiv Hydroelectric Station (completed in 1968, 361,200 kW), and the thermal Trypillia Regional Electric Station (completed in 1972, 1.8 million kW). Since 1991, most of the thermal power stations have been privatized (Ukr-Can Power, Kyivenerho, Akademteploenerho), while the hydroelectric power stations on the Dnipro River remain as part of the state joint-stock hydro power engineering generating company, ‘Dniprohydroenergo’, headquartered in Vyshhorod, on the northern perimeter of Kyiv. Privatization helped in funding the renovation of the outdated power-generating technologies and worn out facilities.

A large part of Ukraine’s industrial output is produced by Kyiv’s enterprises. In 1994, for example, Kyiv had 5.1 percent of Ukraine’s population, but produced 6.6 percent of all the consumers goods produced in Ukraine (by value), including 3.6 percent of all the processed food and 11.5 percent of the non-edible consumer goods, including 12.2 percent of the textiles, clothing, and footwear. The production of some goods was significantly more concentrated in Kyiv. For example, in 1983, 100 percent of all motorcycles, 40 percent of all tape recorders, 26.2 percent of all chemical fertilizers, 10.9 percent of all excavators, and 16.7 percent of all chemical fibers were produced there.

Kyiv’s industries are greatly dependent on the intellectual and technological base provided by the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and various research institutes housed in Kyiv for the research and development of new technologies. Hence, Kyiv’s industries also account for the building of a significant portion of Ukraine’s advanced industrial machines, precision tools and instruments, armatures, food-processing and chemical-processing equipment, aircraft, watercraft, hydraulic elevators, electrical equipment and electronic instruments, computers, audio and video equipment, cameras, optics, printing and sowing machinery, and road-construction machinery. Kyiv also has enterprises in chemical processing and pharmaceuticals, metal working, and the making of wood products and furniture, building materials, printing, textiles, clothing, foodstuffs, leather goods and consumer products.

The decline of state orders, particularly in the Military-Industrial Complex, required manufacturers to seek restructuring and adjustment to civilian markets. Many sought this transition through privatization and partnership with foreign firms. For example, the Antonov Aeronautical Scientific Technical Complex, which has been designing and building various kinds of aircraft in Kyiv since 1952, became known for its short take-off and heavy-lift aircraft, capable of passenger or cargo service, suitable for both civilian and military needs. In order to maintain leadership in its niche and try to penetrate the global market, it has become a state-controlled corporation seeking partnership with other aircraft builders, such as Boeing. Its planes and spare parts, and now trolley buses, are built at Aviant, a separate state enterprise in Kyiv; spare parts for planes as well as medical and household equipment (vacuum cleaners, fans) are now built at the Artem enterprises, a state holding company that passed from the Military-Industrial Complex to the City of Kyiv. The Kyiv Motorcycle Factory, by contrast, became a joint-stock company, and has adopted stringent quality control to supply its vehicles and spare parts to Belgium, Italy, Spain and the United States. Similarly, the shipbuilding firm ‘Leninska kuznia’ (Lenin’s smithy) became a joint-stock company, has built a number of sea-faring trawlers, specialty vessels for the Russian corporation, Gazprom, and has been noticed by commercial interests in the Netherlands and the UK.

Kyiv is the major transportation hub of Ukraine. Kyiv has a central railway station (built in 1870, re-built in 1932, 1945, 1980, 1997, a new southern addition in 2001) that provides inter-city passenger service to all parts of Ukraine and abroad and serves as a hub of the suburban commuter service; the central bus depot Avtovokzal (from 1961) that services 50 intercity routes; four airports: the Zhuliany airport (from 1924, mostly domestic flights, in need of renovation), the Boryspil international airport (near Boryspil, from 1959, re-built since 1998), the small Sviatoshyn airport serving the Aviant aircraft factory (in the western part of the city), and the Hostomel Cargo Airport (northwest of Hostomel, northwest of Kyiv), with its large modern landing strip, used by the Antonov company for flight training on the largest cargo planes in the world. Kyiv also has an important river port, from which at its peak years in the late 1970s and early 1980s some 22 to 30 million tons of cargo and 4 to 5 million passengers were transported per year. Seven major bridges join Left- and Right-Bank Kyiv: Paton (completed in 1953) and Moscow (1976) automobile bridges, the Podil (Petrivskyi) (1929) and Darnytsia (1949) railway bridges, the Metro Bridge (1965) and its extension the Rusanivka Bridge (1957), the pedestrian Park Bridge (1957) from the center to Trukhaniv Island (and the Central Park of Culture and Recreation) in the Dnipro River, and the Pivdennyi (Southern) Bridge (1990), which has a separate Metro section and three lanes of automobile traffic in each direction. Two additional automobile bridges, one of which would also accommodate a Metro line, have been started with the view to alleviate heavy traffic. Six major highways guide auto traffic in and out of Kyiv. Within the city transportation is provided by streetcars (since 1891, first in the Russian Empire), trolley buses (since 1935; in 1998 had 35 routes served by 640 vehicles that carried 448 million passengers), and a subway system, called Metropoliten. Construction of the Kyiv metro, undertaken by the state enterprise ‘Kyivmetrobud,’ began in 1949, with the first line of 5 stations opened in 1960. Presently it has three intersecting lines of nearly 60 km service and 44 stations; 434 million passengers were transported in 1998. Plans for expansion to 2020 include the extension of several lines and the addition of two more intersecting lines. City buses (over 2000 in service, on 164 bus routes, transported 323 million passengers in 1998) and taxis are also used. Since 1991 private taxis and micro-buses have gained usage, as have privately-owned vehicles, placing a heavy traffic load on city streets. This burden has not been alleviated even with the reconstruction of the Khreshchatyk (1998) and the completion of the Great Circular Road north of Kyiv (2001).

Water supply is an essential attribute of urban development. Kyiv obtained its drinking water from wells and from the Dnipro River (piped since 1872). As the city grew, its central water supply from the river expanded, and by 1961 it also tapped the Desna River. By 1981 over 1.3 million cubic meters of water were supplied by the utility, or 370 liters per resident of Kyiv. Since the Chornobyl nuclear disaster (1986) and the fear of radionuclides in the Dnipro water, the supply has been expanded to a greater use of artesian groundwater (160 sources, 20 percent of the city’s water) and reliance on the Desna River (1999).

In public health, Kyiv is also a leader. Public medical practices have a long history in Kyiv, reaching back to the 11th century Kyivan Cave Monastery. In 1715 the first government drugstore and in 1728 the first private drugstore was established in Kyiv. In 1755 a hospital was established in Kyiv. The first faculty of medicine was established at Kyiv University in 1841. Various prominent medical practitioners worked in Kyiv, such as the surgeons Nikolai Pirogov and Mykola Volkovych, the pathologists Volodymyr Pidvysotsky, Volodymyr Vysokovych and Danylo Zabolotny, the pathophysiologist Oleksander Bohomolets, and the therapeutists Vasilii Obraztsov, Mykola Strazhesko and Feofil Yanovsky. Presently Kyiv, as the capital, houses the Ministry of Health. Supporting the policy and administration of the ministry is the Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, also located in Kyiv. Functioning within the system of public health protection in Kyiv in 1998 there were 97 hospitals (including 19 for children), 269 ambulatory and polyclinic institutions, with a total of 32,000 hospital beds. The main constraints on the system were limited financing, shortage of modern equipment and drugs, and slow reorganization of the system. The strength of the system are its leading medical practitioners (surgeons Nikolai Amosov and O. Shalimov, neuro-surgeon A. Romodanov, cardiologist Oleksander Hrytsiuk, endocrinologist Vasyl Komisarenko, gerontologist Dmytro Chebotarov and V. Frolkis, opthalmologist M. Serhiienko), and the advanced medical research conducted in Kyiv.

Ethnic composition. The first ethnic census of Kyiv was conducted as part of the 1874 census by members of the Hromada of Kyiv. At that time, there were three major nationalities: Ukrainians, Russians, and Jews. Up to the Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent formation of the Polish Republic, Kyiv was also inhabited by many Poles, who played an important cultural and economic role there. The number of Jews rose steadily after they were allowed to leave the Pale of Settlement and settle there in 1856 and dropped drastically after many of them were murdered by the Nazis in the Holocaust. Table 4 shows the change in Kyiv’s ethnic composition; the figures for the Russians include a sizable proportion of Russified Ukrainians (‘Little Russians’), particularly in 1874, 1917, and 1920, which accounts for the significant drop in the percentage of Ukrainians between 1874 and 1917. Subsequent rapid growth of Kyiv’s population resulting largely from an influx of Ukrainians from the countryside and other cities and towns slowly changed the ethnic balance in their favor. Even so, the Russian language retained its dominant status among the Kyivans. In 1979, 52.8 percent of Kyivans claimed Ukrainian as their native language; 44.8 percent claimed Russian. After independence, by 2001, the claim to the Ukrainian language as the native language rose to 72.1 percent while that for the Russian language declined to 25.3 percent. As a result of the influx of some non-traditional immigrants into Kyiv (from East and South Asia), the claim to other native languages increased slightly (from 2.4 to 2.6 percent). The use of Russian is no longer dominant in the city, but given the force of habit, it is still prevalent; while in 1989 87.3 percent of the population spoke Russian, and only 76.3 percent spoke Ukrainian, by 2001 this ratio has reversed, so that 93.7 percent of the Kyivans claimed ability to speak Ukrainian but only 74.7 percent claimed ability to speak Russian.

Education, science, and culture. Kyiv is the cultural and academic center of Ukraine. It houses the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine along with more than 130 of its 160 research institutes in Kyiv. Moreover, its publishing house, Naukova Dumka (Scientific Thought), the National Library of Ukraine, the National Botanical Garden, and the Main Astronomical Observatory are located in Kyiv. Established in 1918 by the Hetman government of Ukraine as the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, it was developed in the Soviet period as the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. With Ukraine’s independence and political changes, research has been re-oriented among the existing institutes. Over 40 new institutes were created to take on neglected tasks, such as the Institute of the Ukrainian Language of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the Institute of Ukrainian Archeography and Source Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. With a shortage of government funding, alternate sources were sought and secured.

In 2000 in Kyiv there were over 360 scientific institutes, or 22 percent of all in Ukraine. Their affiliation represented: government economic sector (57 percent), academic sector (36 percent) higher education (5 percent) and scientific research and development of industrial enterprises (2 percent). Thus over 200 research and development, planning and design institutes were not part of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Probing fields such as economics, politics, pure and applied sciences, technology, and medicine, these institutes are associated with various government ministries of Ukraine, universities, or other non-governmental organizations or enterprises in Kyiv. Among state institutions created in 1991 or later are the Academy of Agrarian Sciences, the Academy of Medical Sciences (with its 13 medical institutes), the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences, the Academy of Engineering Sciences, the Academy of Light Industry, and the Ukrainian Juridical Academy. Among public (non-governmental) institutions are the Academy of Technological Sciences of Ukraine, the Academy of Sciences of Higher Education of Ukraine, the International Slavonic Academy, the Academy of Non-Standard Ideas, and the Academy of Computer Sciences and Systems of Ukraine. Commercial institutes tend to be in applied technology, such as the Institute of Applied Informatics, the scientific-research institutes ‘Buran,’ ‘Kvant,’ and ‘Kvant-navihatsiia’ for various electronic navigation and avionics instruments, and for research and development for various other industries, that formerly belonged to Soviet government ministries of related industries.

Higher education at the post-graduate level is offered at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and some of the research institutes and academies mentioned above. Postsecondary education is offered at 24 universities (15 state and 9 private) and other postsecondary schools in Kyiv. In 2004–5 there were 65 institutions with III-IV accreditation levels in Kyiv (out of a total of 347, or 18.7 percent, in Ukraine as a whole) with 431,400 students enrolled (out of a total of 2,026,700 students, or 21.3 percent, in similar institutions in Ukraine). Enrolment has increased both at the academic and the applied-business teaching institutions since the 1980s. Indicative of the earlier distribution are data for 1983. Then, only 150,800 students were enrolled in Kyiv’s postsecondary schools. However, another 61,900 attended 40 secondary specialized schools; 29,500, in 41 vocational-technical schools; and 313,000, in 308 elementary schools.

Presently, the largest postsecondary institutions in Kyiv are: Kyiv National University (named in honor of Taras Shevchenko; established as the Saint Vladimir University in 1834), Kyiv Polytechnical Institute National Technical University of Ukraine (established in 1898), the National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine (founded in 1954 as the Ukrainian Agricultural Academy), Kyiv National Pedagogical University (established as Kyiv Institute of People's Education in 1920, re-organized and re-named in 1930, 1933, 1936, and re-named again in 1991, and designated a university in 1993, and national university in 1997), Kyiv National Economic University (established as Kyiv Commercial Institute in 1908, changed to Kyiv Institute of the National Economy in 1920), Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture (est 1930 as Kyiv Construction Institute, re-named in 1939 the Kyiv Civil-Engineering Institute), the National Medical University, Kyiv National University of Culture and Arts, and the National University of Physical Education and Sport of Ukraine. Other state universities in Kyiv are Kyiv National Linguistics University (founded in 1948), the National Aviation University (founded in 1933; instructions in Ukrainian, Russian and English), Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design, Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics (founded in 1966), the National Transport University, and the National University of Food Technologies. Other postsecondary schools include Kyiv Higher Bank School, Kyiv Institute of Communication, the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture, the National Music Academy of Ukraine, the National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, Kyiv State Maritime Academy, the Ukrainian Academy of Foreign Trade, and the Ukrainian Academy of Public Administration under the President of Ukraine.

Among the non-state universities, the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (established as the Kyivan Mohyla College in 1615, designated academy since 1701, reduced to a seminary in the late 18th century, closed down in 1817, reopened in 1819 as Kyiv Theological Academy, closed in 1918 and converted to the Dnipro Naval Academy in 1920) was re-established as a university in 1991, with instruction in Ukrainian and English, to educate the Ukrainian elite. Other private institutions include the International Solomon University (founded in 1991, has a branch in Kharkiv), Kyiv International University (founded in 1994 as the International Institute of Linguistics and Law and renamed in 2002), the European University of Finance, Information Systems, Management and Business (founded in 1992), Kyiv Economic Institute of Management (founded in 1992, instruction in Russian and English) and Kyiv Institute Slavonic University (founded in 1993, instruction in Ukrainian, Russian, English, German, French).

In the Soviet period Kyiv hosted the executives of the Writers' Union of Ukraine, Union of Artists of Ukraine, Union of Composers of Ukraine, Union of Cinematographers of Ukraine, Union of Journalists of the Ukrainian SSR, and Union of Architects of Ukraine. Although in the post-Soviet period such unions no longer have the official privileges and duties to the state they had then, their executives remain in Kyiv, since most of the prominent intellectuals and artists of Ukraine continue to work and live here.

There are over 1,000 libraries in Kyiv, including Ukraine’s largest, the National Library of Ukraine (over 14 million volumes), the National Parliamentary Library of Ukraine (formerly the Republican Library, over 4 million volumes), the Library of the Supreme Council of Ukraine (Verkhovna Rada) (mostly legislation documents, electronic resources), the Kyiv National University Library (over 3 million volumes), the Kyiv Polytechnical Institute National Technical University of Ukraine Library (over 2.5 million volumes), libraries of 22 other universities, the National History Library of Ukraine (over 800,000 volumes), specialized Medical, Agricultural, and Technical libraries, libraries at the other 41 postsecondary schools, and about 150 city central libraries for adults, youths, and children.

There are about 30 government-funded museums in Kyiv: the Natural History Museum; the National Museum of the History of Ukraine; the National Art Museum of Ukraine, the National Museum of Ukrainian Decorative Folk Art, the Kyiv Picture Gallery National Museum, the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, and the Museum of Theater, Music, and Cinema Arts of Ukraine; the National Kyivan Cave Historical-Cultural Preserve (established in 1926, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990, with several museums on its territory); Saint Sophia Museum (a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990); the Museum of Kyiv’s History (opened in 1982 at the Klovsky Palace, 1753–5); the National Museum of Literature of Ukraine (opened 1986); the Kyiv Shevchenko Museum; the Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine, the Museum of Sports Fame of Ukraine, Kyiv Museum of Pedagogy, the Museum of the Book and Printing of Ukraine, and the Kyiv Museum of Folk Architecture and Folkways; literary memorial museums dedicated to Lesia Ukrainka, Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Lysenko, Maksym Rylsky, Oleksander Korniichuk, Hryhorii Svitlytsky, Pavlo Tychyna, Viktor Kosenko and Ivan Honchar; the Museum of Chornobyl; the Museum of the Ukrainian Hetmans; the Aleksandr Pushkin Museum; the State Aviation Museum and the Memorial Complex of the Great Patriotic War. There are also over 40 smaller museums organized and run by private individuals, three observatories (the Main Astronomical Observatory [est 1944], the Kyiv Astronomical Observatory [1845], and the Ukrainian Meteorological Observatory [1855]), a planetarium (1952), two botanical gardens (1839 and 1936), and a zoo (1908).

In 1987 there were 12 professional theaters in Kyiv: the Kyiv Theater of Opera and Ballet, Kyiv Ukrainian Drama Theater, Kyiv Russian Drama Theater, Kyiv Operetta Theater, Kyiv Young Spectator's Theater, Kyiv Puppet Theater, Kyiv Druzhba Theater, Kyiv Theater of Comedy and Drama, Kyiv Variety Theater, Kyiv Theater of Historical Portrayal, Kyiv Music Hall, and Kyiv Young People's Theater. By 2001 Kyiv had 22 theaters, that also included the Actor Theater, the Podil Drama Theater, the Koleso (Circle) Theater, the Small Drama Theater, and the Plastic Drama on Pechersk Theater. Altogether they presented about 3,000 performances that were visited by nearly 500,000 spectators. Professional musical ensembles include the National Philharmonic of Ukraine, the DUMKA Chorus, the State Banduryst Kapelle of Ukraine, the Kyiv Kamerata Chamber Orchestra, the Kyiv Chamber Choir, the Verovka State Chorus, the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, Revutsky Men’s Chorus, the State Dance Ensemble of Ukraine, Dance and Song Ensemble of the Kyiv Military District, Kyiv Folk Instrument Orchestra, and Lysenko String Quartet. The Kyiv Circus has existed since the 1860s.

Kyiv has been the center of Ukrainian film and mass media. In 1928 the Kyiv Artistic Film Studio was founded there. Also located in Kyiv are the Kyiv Studio of Chronicle and Documentary Films, the Kyiv Studio of Popular Science Films, and the Ukrtelefilm studio (est 1966). In 1981 there were 136 cinemas in Kyiv. Kyiv has had radio stations since 1927. Presently they include not only AM, short wave and FM broadcasts (19 stations), but also internet radio (5 stations). Before independence, republican TV programs were broadcast daily in Ukrainian and Russian on three television channels from a telecenter established in Kyiv in 1951 and enhanced with a 380 m transmission tower (the highest of that type of free-standing structure in the world at the time) in 1973. Since independence the number of television channels has increased to 8, and the number of companies with studios and programming to 19.

Publishing. Kyiv has always been an important publishing center in Ukraine; since the 1930s it has been the pre-eminent one. In 1917–18, there were 20 publishing houses, over 40 newspapers and journals, and 15 bookstores in Kyiv. In the Soviet period, only government publishers were allowed. By 1987 there were 16 publishing houses: Politvydav Ukrainy, Molod, Radianskyi Pysmennyk, Radianska Ukraina, Derzhavne Vydavnytstvo Ukrainy, Naukova Dumka, Vyshcha Shkola, Radianska Shkola, Mystetstvo, Tekhnika, Budivelnyk, Znannia, Muzychna Ukraina, Urozhai, the Dnipro publishing house, and the publishing house of the Ukrainska Radianska Entsyklopediia. Since independence, while the number of government book publishers increased to 22 (and some of the names of publishers have been changed or modified), nearly a thousand publishers of other forms of ownership have emerged in Ukraine. Nearly half of them are located in Kyiv. Among them are the publishers from Russia, who now prepare and print ‘Ukrainian’ editions in the Russian language of the former Soviet flagship newspapers, such as the daily Izvestiia, and Komsomol’skaia pravda, and the weekly Argumenty i fakty; the formerly Ukrainian diaspora publishers, such as Smoloskyp (Baltimore, 1967–92, Kyiv, 1992–), Shliakh Peremohy (Munich, 1954–92, then Lviv, 1992–6, and Kyiv, 1996–) and the publishers of Suchasnist’ (Munich, 1961–90, Newark, N.J., 1990–8, Kyiv, 1998–); and foreign-owned western publishers, such as Jed Sunden (a US citizen), who started KP Publications in Kyiv and publishes the weekly Kyiv Post (1995–), the IntelNews, Inc. (Baltimore, office in Kyiv), which publishes the IntelNews Business Journal (1996–), the Matlid Publications (Chicago), which publishes the weekly Eastern Economist (1994–) and the EE Daily, the Blitz-Inform Press (Kyiv) which, affiliated with Paul Winner Consultants Ltd. (London) and Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga (Moscow), publishes the monthly Ukrainian Business Journal (1994–), Evolution Media (Kyiv), owned by Media Consulting (Leipzig, Germany), which publishes the Kyiv Weekly (2002–), and the Willard Group (United Kingdom), which publishes The Ukrainian Observer (2001–). Non-government institutions also publish in English: the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development publishes Welcome to Ukraine (1994–), the RFE/RL Research Institute and the Ukrainian Independent Information Agency jointly publish Ukraine Today (1994–), the Ukrainian-European Policy and legal Advice Centre publishes Ukrainian Economic Trends: Monthly Update (1998–) and Ukrainian Economic Trends: Quarterly Issue (1999–) and the Center for Peace, Conversion and Foreign Policy of Ukraine publishes the Ukrainian Monitor (Kyiv, 2001–). In the period of seven years from 1991 to 1998 about 21 thousand titles of books were released in Kyiv with a total run of nearly 300 million copies.

Kyiv is the major printing center in Ukraine. In 1987, the association Polihrafknyha, consisting of six printing enterprises in Kyiv and six elsewhere, printed and bound 95 percent of all the books published in Ukraine. Such concentration is no longer the case, as an increased number of titles are published and printed in the cities of other parts of Ukraine.

In 1987 many newspapers and periodicals were printed in Kyiv: 14 republican newspapers (including the daily Radians’ka Ukraïna, Pravda Ukrainy, Robitnycha hazeta (Kyiv), Sil’s’ki visti, Molod’ Ukraïny, and Komsomol’skoe znamia, the semiweekly Radians’ka osvita (Kyiv), and the weeklies Kul’tura i zhyttia, Literaturna Ukraïna, and Druh chytacha), a weekly aimed at the Ukrainian diaspora Visti z Ukraïny (and its English-language edition, News from Ukraine), the city daily Vechirnii Kyïv, the oblast dailies Kyïvs’ka pravda and Moloda hvardiia, 55 republican periodicals (including the popular weekly Ukraïna, the biweeklies Perets’ and Pid praporom leninizmu, and the monthlies Komunist Ukraïny, Vitchyzna, Prapor, Dnipro, Vsesvit, Kyïv, Barvinok, Raduga, Nauka i suspil’stvo, Novyny kinoekranu, and Radians’ka zhinka), and 40 periodicals of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

With Ukraine’s independence in 1991, more new official government publications appeared: Holos Ukraïny: hazeta Verkhovnoï Rady Ukraïny (Voice of Ukraine: Newspaper of the Supreme Council of Ukraine; daily, since 1 January 1991), Uriadovyi kurier: hazeta Kabinetu ministriv Ukraïny (Official Courier: Newspaper of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine; irregular, 24 issues in 1991, 3 issues a week in 1992-), Vidomosti Verkhovnoï Rady Ukraïny (News of the Supreme Council of Ukraine; weekly, 1991–), Viche (monthly, 1992–), and Zibrannia postanov uriadu Ukraïny (the monthly collection of decisions of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, 1992–). The city council also added two official periodicals: the new city daily Khreshchatyk (since 1990, now 3 times per week), and the city’s analytical weekly, Ukrains’ka stolytsia (a continuation of Stolytsia [3 times per week, 2001–6]). Of the pre-1991 periodicals, some changed their titles: the daily Radians’ka Ukraïna to Demokratychna Ukraïna (3 times/week), Radians’ka osvita (Kyiv) to Osvita, Radians’ka shkola to Ridna shkola, Radians’ka zhinka to Zhinka, the monthly Radians’ke literaturoznavstvo to Slovo i chas, the monthly Sotsialistychna kul’tura to Ukrains’ka kul’tura; most continued to publish, but with greater market segmentation, many lost readership, including Pravda Ukrainy, Robitnycha hazeta, Sil’s’ki visti (now 3 times per week), Molod’ Ukrainy (3 times per week), Kul’tura i zhyttia, Literaturna Ukraïna, Druh chytacha, Visti z Ukraïny, Vechirnii Kyïv, Kyïvs’ka pravda (3 times per week), Perets’, Moloda hvardiia, Vitchyzna, Dnipro, Vsesvit, Kyïv, Nauka i suspil’stvo, Ukraïns’kyi teatr, and Novyny kinoekranu); still others ceased publication, like Komsomol’skoe znamia (–1991), Komunist Ukraïny (–1991), and Ukraïna (–2005). Meanwhile, with the desire to express different views and needs, the number of newspapers mushroomed throughout the cities of Ukraine, including Kyiv. New periodicals in Kyiv reflect a proliferation of public and political opinion and an expansion of business and tabloid publications. The former include the dailies Den’ (5 times per week, 1996–), Fakty i kommentari (6 times per week, 1999–), Kyïvs’kyi visnyk (5 times per week, 1992–2002), Ukraïna moloda (5 times per week, 1991–), Kievskie vedomosti (5 times per week, 1992–), Vechernie vesti (in Russian, 5 times per week, 2000–); among the weeklies, the Rukh weekly, Narodna hazeta (Kyiv) (1990–), the Ukrainian Republican Party weekly, Samostiina Ukraïna (1991–), the news analysis of Zerkalo tyzhnia (in Russian as Zerkalo nedeli, or Mirror-Weekly, 1994–),the monthlies Rozbudova derzhavy (1994–), Ukraïns’kyi svit (1992–), Trybuna: Hromads’ko-politychnyi i naukovo-metodychnyi zhurnal Tovarystva ‘Znannia’ Ukraïny (1992–), Suchasnist’ (Munich, 1961–90, Newark, N.J., 1990–8, Kyiv, 1998–), Kino (1998–), the bi-monthlies Viis’ko Ukraïny (1992–), Studii Politolohichnoho tsentru "Heneza" (1993–) Vidrodzhennia (1998–2000), the quarterlies Pamiatky Ukraïny (1989–), Ukraïna s’ohodni: polityka, ekonomika, kul’tura (irregular, 1999–), Relihiina panorama (2000–), Moloda Ukraïna (2003–), and the annual Moloda natsiia (Young Nation, 1996–, published by the Smoloskyp publishers of the Ukrainian Helsinki Association); business-oriented publications include the trade weekly Posrednik (Mediator, in Russian, 1991–), the business weeklies for Ukraine, Dilova Ukraïna (1992–) and Dilovyi visnyk (1992–), the business weekly and website, Halytski kontrakty (Lviv and Kyiv, 1992–), the weekly Delovaia Ukraina (Business Ukraine, in Russian, 1992–, twice a week since 1994), the monthly Ukraïna-Business (1990–), the semi-annual Zolota Fortuna (2000–), the annual Ukrainian market review (in Russian) Obzor ukrainskogo rynka (1999–), the Ukrainian investment weekly InvestHazeta (1995-), the banking, customs and taxation weekly, Konsul’tant (1998–), and directories, such as the Yellow Pages of the Kyiv Business Directory (in English and Ukrainian, 1996–), Khto ie khto v Ukraïni (Who is Who in Ukraine, 1997–) and Khto ie khto v ukraïnskii politytsi (Who is Who in Ukrainian Politics, 1993–).

Most periodicals published by the various institutes of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and other learned institutions of Kyiv (and their numbers have increased since independence) are printed in the city. Religious institutions based in Kyiv also print their publications in Kyiv. Internet has also become an important component of information services. In the reporting and analysis of news, the internet-based daily Ukraïns’ka pravda (April, 2000–) became an important source of news, and particularly of stories and analyses critical of the Ukrainian government and the wealthy ‘oligarchs.’ For that courage, its cofounder and journalist-editor, Heorhii Gongadze, was kidnapped and murdered (September, 2000).

The Radio and Telegraph Agency of Ukraine, established in Kharkiv (the capital of Soviet Ukraine at that time) in 1921, has been based in Kyiv since 1934, serving the Ukrainian SSR as part of the USSR network of information agencies. Since independence (1991), the agency was re-named the Ukrainian National Information Agency (Ukrinform), aka the National News Agency of Ukraine. With its headquarters in Kyiv, it has branch offices in Crimea, Donetsk, Lviv and Kharkiv, and correspondents throughout Ukraine and in many countries abroad. Other news agencies in Kyiv include the offices of Associated Press, Bridge News, Express Inform, Hungarian News Agency, Intelnews (Ukraine’s English-language news), Interfax-Ukraine (with its website), IREX ProMedia (based in Washington, DC), Reuters (London, UK), Ukrainian News, the Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (UNIAN), and the Russian-language UNIAR. Ukraine’s internet provider is also based in Kyiv.