IEU'S FEATURED TOPICS IN UKRAINIAN HISTORY

I. The Trypilian Culture and the Neolithic Period and Copper Age in Ukraine

II. The Iron Age in Ukraine: The Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians

III. Ancient City-States on the Northern Black Sea Coast

IV. The Kyivan Rus' State and its Ukrainian Principalities

V. Volodymyr the Great and the Christianization of Rus'-Ukraine

VI. Kyivan Rus' 1015-1132: From Yaroslav the Wise to Mstyslav the Great

VII. The Medieval Principality of Galicia-Volhynia

VIII. Ukraine in 14th-16th Centuries: The Lithuanian-Ruthenian State

IX. Ukraine under Polish Control in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th and 17th Centuries

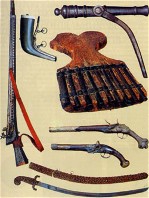

X. The Origins and Early History of the Ukrainian Cossacks

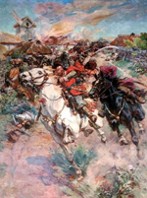

XI. Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Ukrainian-Polish War, and the Pereislav Treaty of 1654

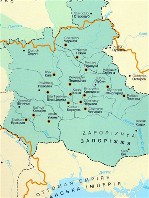

XII. The Cossack Hetman State (1648-1782)

XIII. The Period of "the Ruin" and the Partition of Ukraine in the late 17th Century

XIV. Hetman Ivan Mazepa, Tsar Peter I, and the Battle of Poltava (1709)

XV. The Haidamaka Uprisings of the 18th Century

XVI. The Last Rulers of the Hetmanate and the Dissolution of Ukrainian Autonomy

XVII. The Revolution of 1848-9 and the Emergence of the Ukrainian Political Movement in Western Ukraine

XVIII. Ukrainian Populism and Its Grass-Roots "Organic Work" in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century

XIX. Women's Education and Women's Movement in Ukraine

XX. The Ukrainian Co-operative Movement

XXI. The Revolution of 1905 and the Ukrainian Political Life in Russian-Ruled Ukraine

XXII. The The Struggle for Independence, 1917-20 (1): The Central Rada Period

XXIII. The Struggle for Independence, 1917-20 (2): The Ukrainian Armed Forces Battling for Ukraine's Independence

XXIV. The Struggle for Independence, 1917-20 (3): The Hetman Government and Ukrainian State

XXV. A Battle for Ukraine: The Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917-21

XXVI. The Western Ukrainian National Republic and the War in Galicia, 1918-19

XXVII. The Ukrainian Galician Army: The Regular Army of the Western Ukrainian National Republic

XXVIII. The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and the Revival of Ukrainian Orthodoxy

XXIX. National Communists and the Ukrainization Policies in the 1920s

XXX. The Stalinist Collectivization Campaign and the Famine-Genocide of 1932-3

XXXI. Second World War in Ukraine: Phase 1, 1939-1941

XXXII. Second World War in Ukraine: Phase 2, 1941-1944

XXXIII. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army: The Second World War Combatants in Ukraine

XXXIV. Ukrainians during the First Postwar Years: 1945-47

XXXV. Ukraine under Nikita Khrushchev and Petro Shelest

XXXVI. Ukraine under Leonid Brezhnev and Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

XXXVII. The Perestroika Period and Ukraine's Declaration of Sovereignty

XXXVIII. The Re-establishment of Ukrainian Independent Statehood in 1991

I. THE TRYPILIAN CULTURE AND THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD AND COPPER AGE IN UKRAINE

I. THE TRYPILIAN CULTURE AND THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD AND COPPER AGE IN UKRAINE

Perhaps the most sophisticated culture of the early Neolithic Period in Europe, the Tripilian culture existed on Ukrainian territories for over three millennia. During the 6th millennium BC, Trypilian tribes began settling in low-lying riverbank areas and on plateaus in the Dnieper River and Boh River basins. They were, most probably, primitive agricultural and cattle-raising tribes that migrated to Ukraine from the Near East and from the Balkans and Danubian regions. Scholars have identified three periods in the development of this culture--early (5400-3500 BC), middle (3500-2750 BC), and late (2750-2250 BC). The differentiation of periods is characterized by an increase in population and the geographic spread of the culture as well as by changes in settlement patterns, the economy, and the spiritual life of the people. (A detailed discussion of the Tripilian culture can be found, among others, in volume 1 of Mykhailo Hrushevsky's fundamental History of Ukraine-Rus'.) As a result of incursions by other cultures (particularly the Pit-Grave culture) into Ukrainian territory during the Copper Age in the mid-3rd to early 2nd millennium BC, many characteristic Trypilian traits changed, were absorbed by other tribes, or disappeared... Learn more about the Trypilian culture and the Neolithic Period and Copper Age in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

|

NEOLITHIC PERIOD. The closing phase of the Stone Age, lasting in Ukraine from ca 5000 to 2500 BC. The Neolithic Period was characterized by the development of agriculture and pottery manufacturing, the establishment of sedentary agriculturally based settlements, the use of polishing techniques for stone tools, the emergence of increasingly complex systems of religious belief, and the growth of tribal social orders. This epoch was also marked by the existence of a greater diversity of cultures than in either the Paleolithic Period or Mesolithic Period. By far the most developed culture was the agrarian Trypilian culture, which existed throughout most of Right-Bank Ukraine until the Bronze Age. Other groups that existed during this period include the Pitted-Comb Pottery culture, the Serednii Stih culture, and the Boh-Dniester culture. The Neolithic Period ended with the introduction of metal technology during the Copper Age... |

| Neolithic Period |

|

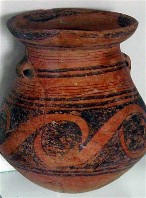

TRYPILIAN CULTURE. A Neolithic-Bronze Age culture that existed in Right-Bank Ukraine ca 5400 to 2000 BC. It is named after a site near Trypilia in the Kyiv region uncovered by Vikentii Khvoika in 1898. The major economic activities of the early Trypilians were agriculture and animal husbandry, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and food gathering. The basic tools of the Trypilian culture were made of stone, bone, and flint. Some bronze items, especially fishhooks, bracelets, and rings, have been found at Trypilian excavations. The Trypilian culture is especially known for its ceramic pottery. In the early period, handbuilt large vessels for storing grains, pots, plates, colanders, and the like were all common. Earthenware was also used to make figurines of women, scale models of homes, jewelry, and amulets. The exterior of the pottery was decorated with inscribed ornamentation in the form of spiralling bands of parallel double lines... |

| Trypilian culture |

|

KHVOIKA, VIKENTII (Czech: Chvojka), b 1850 in Semin, near Prelouc, Bohemia, d 2 November 1914 in Kyiv. A pioneering Ukrainian archeologist of Czech origin. As an active member of the Kyiv Society of Antiquities and Art, he helped found the Kyiv City Museum of Antiquities and Art in 1899; he became the director of its archeological department in 1904. From 1893 to 1903 Khvoika discovered, excavated, and studied the Kyrylivska settlement in Kyiv and other Paleolithic sites, sites of the Neolithic Trypilian culture, Bronze Age and Iron Age tumuli and fortified settlements in Ukraine's forest-steppe, and the 'burial fields' of cremation urns and settlements of the Zarubyntsi culture and the Cherniakhiv culture. He was a leading proponent of the theory that the Slavic inhabitants of the middle Dnieper Basin were autochthonous. He also excavated and studied medieval palaces, fortifications, and churches in Chyhyryn (1903), Kyiv, and Bilhorod... |

| Vikentii Khvoika |

|

PIT-GRAVE CULTURE (or Yamna culture from yama [pit]). A Copper Age-Bronze Age culture of the late 3rd to early 2nd millennium BC that existed along the Dnieper River, in the steppe region, in the Crimea, near the Danube estuary, and in locations east of Ukraine (up to the Urals). This culture took its name from pit graves used for burials in family or clan kurhans. Corpses were covered with red ocher and laid either in a supine position or on their sides with flexed legs. Grave goods included egg-shaped pottery containing food, stone, bone, and copper implements, weapons, and adornments. The culture's major economic occupation was animal husbandry, with agriculture, hunting, and fishing of secondary importance. The people of this culture usually lived in surface dwellings in fortified settlements. They had contacts with tribes in northern Caucasia and with Trypilian culture tribes in Ukraine... |

| Pit-Grave culture |

|

KURHAN. A term from the Turkic word for mound or stronghold, used in Eastern Europe for a tumulus or barrow, that is, an earthen or stone mound built over a grave. Kurhans first appeared in the steppes north of the Caspian Sea and Black Sea and in Subcaucasia and Transcaucasia during the upper Neolithic Period and the Copper Age (3rd century BC). They vary in height from 3 to over 20 m, and in diameter from 3 to over 100 m. The oldest kurhans in present-day Ukraine date from the early period of the Pit-Grave culture. Sometimes the mound was encircled by a cromlech and topped by a stone baba, an anthropomorphic statue. The dead were interred or cremated and deposited together with their worldly goods and valuables in timber graves, vaults, catacombs, or pits. Kurhans were then thrown up over them. They usually occur in groups, indicating that clans and tribes had designated burial grounds... |

| Kurhan |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries dealing with the Trypilian culture and the Neolithic Period and Copper Age in Ukraine were made possible by a generous donation from BOHDAN AND ALEXANDRA BULCHAK of Toronto, ON, Canada.

II. THE IRON AGE IN UKRAINE: THE CIMMERIANS, SCYTHIANS, AND SARMATIANS

II. THE IRON AGE IN UKRAINE: THE CIMMERIANS, SCYTHIANS, AND SARMATIANS

The oldest known Iron-Age settlers in the Ukrainian territories were the nomadic Cimmerians who settled there around 10th century BC. In the 8th century BC, the territories of today's Ukraine came under the control of the Scythians, tribes of nomadic horsemen who founded an empire that stretched from the Danube River in the west to the Ural Mountains in the east. The Scythians were divided into several major tribal groups. Agrarian Scythian groups lived in what is now Poltava region and between the Boh River and the Dnieper River. The lower Boh River region near Olbia was inhabited by Hellenized Scythians, known as Callipidae; the central Dniester River region was home to the Alazones; and north of them were the Aroteres. The kingdom was dominated by the Royal Scythians, a small but bellicose minority in the lower Dnieper River region and the Crimea that had established a system of dynastic succession. The Scythians reached their apex in the 4th century BC under King Ateas, who united all the tribal factions under his rule. Subsequently they began a period of decline brought about by constant attacks by the Sarmatians. The Scythians were forced to abandon the steppe to their rivals and re-established themselves in the 2nd century BC in Scythia Minor, with their capital in Neapolis in the Crimea. The onslaught of the Ostrogoths in the 3rd century AD and the Huns in the 4th century broke the power of the Scythians and Sarmatians, who subsequently disappeared as ethnic entities and assimilated into other cultures. They were largely forgotten, but interest in them was revived as a result of some spectacular finds of Scythian gold treasures in the burial mounds in Ukraine and the Kuban, starting from 1763... Learn more about the times of the Scythians and Sarmatians on the Ukrainian territory by visiting the following entries:

|

CIMMERIANS. Oldest settlers of southern Ukraine, mentioned by Homer (ca 8th century BC) and by Herodotus in his History (5th century BC). Their origin is unknown, but the majority of scholars consider them to be Indo-Europeans. In linguistic terms, on the evidence of the recorded names of their leaders--Tygdamme (in Herodotus, Lygdamis) and his son Sandakhsatra--they are considered members of Iranian tribes. According to Herodotus, the Cimmerians were driven from the steppes by the Scythians in the 7th century BC: some of them settled on the southern shore of the Black Sea (in the Crimea they were known as Taurians), while others waged a campaign in Asia Minor, taking Sardis, the capital of Lydia, in 652 BC. This marked the Cimmerians' apex of power: subsequently they declined and became extinct. Although their culture has been little studied as yet, some scholars believe that the numerous settlements and burial mounds in southern Ukraine dating from the late second and early first milleniums BC are archeological remains of the Cimmerian age... |

| Cimmerians |

|

SCYTHIANS. A group of Indo-European tribes that controlled the steppe of Southern Ukraine in the 7th to 3rd centuries BC. According to the most predominant theories, they first appeared there in the late 8th century BC after having been forced out of Central Asia. The Scythians were related to the Sarmatians and spoke an Iranian dialect. After quickly conquering the lands of the Cimmerians they pursued them into Asia Minor and established themselves as a power in the region. In the 670s BC they launched a successful campaign to expand into Media, Syria, and Palestine. They were forced out of Asia Minor early in the 6th century BC by the Persians, and retreated to their lands between the lower Danube River and the Don River, known as Scythia. The bellicose Scythians were often in conflict with their neighbors. They faced a great military challenge around 513-512 BC, when the Persian king Darius I led an expeditionary force against them. The Scythians forced the Persians to retreat and confirmed their position as masters of the steppes... |

| Scythians |

|

SCYTHIA. The domain of the Scythians. According to Herodotus Greater Scythia occupied a large rectangle of land extending nearly 700 km (20 days travel) from the Danube River in the west across the Black Sea coast and steppe region of what is today Ukraine to the lower Don Basin in the east. Individual Scythian settlements also existed in what is today the Hungarian-Romanian borderland, probably as outposts. It is not known how far north Scythia reached into the forest-steppe zone. By the end of the 5th century BC the Kamianka fortified settlement, near present-day Nikopol, had been established as the capital of Scythia. The Scythians were forced out of the steppe into Scythia Minor--the Crimea (where they established their new capital of Neapolis) and the Dobrudja region south of the Danube Delta--in the 3rd century BC by the Sarmatians. The steppe of Southern Ukraine was occasionally referred to as Scythia (Skufia and Great Skuf in the Primary Chronicle) and Sarmatia until the 19th century... |

| Scythia |

|

SCYTHIAN ART. The art of the Scythians combined Eastern elements with influences from the Hellenic ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. The combination gave the art an exquisite and unique quality. The center of Scythian art can be considered Panticapaeum, the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom. The many Scythian artifacts found in burial mounds in Southern Ukraine and the Kuban were either imported from Greece or made by indigenous Hellenic and Scythian artisans. Scythian jewelery in particular attained a high level of intricacy and magnificence. The principal feature of Scythian art is its use of a zoomorphic symbology. Objects found in Ukraine are distinguishable from their Caucasian counterparts, which reflect more the influence of Iranian and other eastern traditions. The Scythians fashioned gold objects depicting semirecumbent stags, deer, lions, horses, and other animals, as well as human faces and figures. Numerous vases and other objects portray scenes from everyday life as well as motifs from Greek mythology and history... |

| Scythian art |

|

NEAPOLIS. A Scythian city located on the Salhyr River southeast of Symferopol, Crimea. Founded in the 3rd century BC, Neapolis quickly grew into a substantial trade and crafts center. The Scythians established their capital there in the 3rd century BC after being forced south from the Black Sea steppe by the Sarmatians. Neapolis reached the zenith of its influence in the 2nd century BC under kings Skhilouros and Palakhos. The Scythians' power was checked in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD by the Bosporan Kingdom and during the 3rd and 4th centuries Neapolis fell under attacks by Goths and Huns, and the city was abandoned. The city covered an area of approximately 20 hectares. It was surrounded by thick walls with towers. Inside the walls were stone buildings, warehouses, and private homes. Scythians formed a majority of the city's population, but there were also numerous Sarmatians, Taurians, and Greeks. The most striking remains of Neapolis are the mausoleums of the Scythian rulers and burial chambers dug into rock formations... |

| Neapolis |

|

SARMATIANS. A confederation of nomadic Iranian tribes (Aorsians, Alans, Roxolani, Siraces, and Iazyges) related culturally to the Scythians. Originally, in the 7th to 4th centuries BC, they were known as Sauromatians. In the 3rd century BC the Sarmatians conquered the Scythians in the Crimea and thenceforth dominated the steppe between the Tobol River in Siberia and the Danube River. After the 1st century BC the northern coast of the Black Sea was called Sarmatia. The Sarmatians gradually became sedentary after penetrating the Hellenic colonies on the Black Sea coast and settling in the Bosporan Kingdom. They took up agriculture and assimilated into local cultures there and in the forest-steppe region of Right-Bank Ukraine. Their political might was broken by the Ostrogoths in the 3rd century AD and the Huns in the 4th century. Some of the Sarmatians migrated west with the Huns and even reached as far as Spain and northern Africa. Those who remained behind intermingled with the indigenous Slavs and other peoples... |

| Sarmatians |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the times of the Scythians and Sarmatians on the Ukrainian territory were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

III. ANCIENT CITY-STATES ON THE NORTHERN BLACK SEA COAST

III. ANCIENT CITY-STATES ON THE NORTHERN BLACK SEA COAST

From the middle of the 1st millennium BC to the 3rd-4th century AD ancient city-states existed on the northern coast of the Black Sea in today's southern Ukraine. They were founded as colonies of Greek city-states, mainly Miletus and other Ionian states (in today's western Turkey), on sites that had fertile land, were close to good fishing grounds, and facilitated trade with such tribes as the Scythians, Sindians, Sarmatians, and Maeotians. The oldest Greek colony in Ukraine was founded on Berezan Island in the second half of the 7th century BC. The other colonies were founded mostly in the 6th century BC: Tyras (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi), Olbia (on the Dnieper-Boh Estuary), and, in the Crimea, Panticapaeum (now Kerch), Theodosia (now Teodosiia), Tiritaka, Nymphaeum, and Kerkinitis (now Yevpatoriia). Chersonese Taurica, the only Dorian colony, was built at the end of the 5th century BC in southwestern Crimea. In a short time these colonies all became independent, slave-owning poleis. By the late 2nd century BC the states on the northern pontic littoral went into decline, mostly because of expansion by the Scythians and Taurians. In the 330s AD most of these states were economically ruined by the invasions of the Ostrogoths; they were finally destroyed by the Huns in the fourth century... Learn more about the ancient states on the northern Pontic littoral by visiting the following entries:

|

ANCIENT STATES ON THE NORTHERN BLACK SEA COAST. The economy of the ancient city-states in the northern Black Sea coast was based on agriculture (particularly viticulture), manufacturing (stonecutting, construction, metal-working, pottery-making, and jewelry-making), and trade with the neighboring tribes and the cities of Greece and Asia Minor. The colonies sold their own products and acted as intermediaries between Greece and the Black Sea tribes. Most of the states produced their own coins. They sold the local tribes wine, weapons, and such luxury items as sculptures, vases, and precious textiles, and exported grain, dried fish, other agricultural products, and slaves. In political structure most of these states were, like their mother states, slave-owning republics. The Bosporan Kingdom, established ca 480 BC, had a monarchical structure. In the middle of the 1st century BC they came under the protection of King Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus and joined him in his wars with Rome. After Mithradates' defeat Roman garrisons were stationed in many of the states and remained there until the 3rd-4th century AD... |

| Ancient Black Sea colonies |

|

TYRAS. An ancient Greek city-state on the right bank of the Dniester Estuary at the site of present-day Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi. It was established in the 6th century BC by colonists from Miletus. By the 4th century BC it was a prosperous trading center, which even minted its own coinage. Its government was in the hands of five archons, a senate, a popular assembly and a registrar. The types of its coins suggest a trade in wheat, wine and fish. Tyras was sacked in the mid-1st century BC by the Getae, but it revived. It was rebuilt by the Romans and by the early 2nd century AD and it was an important outpost on the frontier of the Roman Empire. In the late 3rd century it was destroyed by the Goths. The site was repopulated much later by the Tivertsians and Ulychians and named Bilhorod. Some preliminary archeological work was done at the site in 1927-32. Systematic excavations under the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR commenced in 1945... |

| Tyras |

|

OLBIA. A major ancient Greek settlement located on the Boh River Estuary in Mykolaiv oblast. Founded in the early 6th century BC by Greek settlers from Miletus and other Ionian cities, Olbia soon became a prominent trading center on the northern Black Sea coast. Its inhabitants engaged in agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, viticulture, various trades, and trade with the Greek metropolis. Olbia imported wine, olive oil, fine dishes, cloth, art objects, and glassware both for itself and for trade with Scythians, Sarmatians, and other tribes on the Pontic steppe in exchange for grain, cattle, wool, fish, and slaves. Olbia reached the height of its prosperity and importance in the 5th-3rd centuries BC as a city-state covering an area of approximately 50 ha. It was strong enough to withstand a major siege by one of Alexander the Great's armies in 331 BC. Subsequent attacks in the 2nd-1st centuries BC by hostile tribesmen weakened the city, and it was forced to accept the suzerainty of Scythian chieftains and then of Mithridates VI Eupator, ruler of the Pontic Kingdom... |

| Olbia |

|

PANTICAPAEUM. An ancient Greek colony founded in the early 6th century BC at the site of present-day Kerch, in the Crimea. Strategically located on the western shore of Kerch Strait, the city grew quickly and before the end of the century it was minting its own coins. As the leading trade, manufacturing, and cultural center on the northern coast of the Black Sea it became the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom, which arose in the 5th century. It was heavily damaged in Saumacus' revolt and Diophantus' capture of the city at the end of the 2nd century BC and by an earthquake ca 70 BC. Panticapaeum was rebuilt under Roman rule, and by the 1st century AD had regained its commercial importance. It began to decline in the 3rd century as tribal raids disrupted the trade in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Basin. Panticapaeum was destroyed by the Huns ca 370. Later a small town arose at the site, which in the Middle Ages became known as Bosphorus. The city was dominated by Mount Mithridates, on which the temples and civic buildings were placed... |

| Panticapaeum |

|

BOSPORAN KINGDOM. An ancient state on the northern coast of the Black Sea, founded ca 480 BC through an alliance of existing Greek city-states. The kingdom's capital was Panticapaeum. It was ruled by the Archaeanactid and then by the Spartocid dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. In the 4th-3rd century BC the Bosporan Kingdom was at the height of its economic and cultural development. It controlled the Taurian Peninsula, the lower Kuban region, and the eastern Azov steppes, which were settled by Maeotian tribes. Apart from the capital of Panticapaeum, other major cities belonging to the kingdom included Tiritaka, Nymphaeum, and Theodosia on the Taurian Peninsula, Phanagoria and Hermonassa in the lower reaches of the Kuban River, and Tanais at the Tanais River estuary (near today's Oziv). The king's power was almost unlimited. Grain growing, orcharding, viticulture, fishing, the skilled trades (particularly artistic metalworking), and trade were highly developed. Its manufactured goods were sold to the neighboring Scythians and Sarmatians... |

| Bosporan Kingdom |

|

CHERSONESE TAURICA or Chersonesus. Ancient Greek city-state in the southwestern part of the Crimea, near present-day Sevastopol. The city was established in 422-21 BC by Megarian Greek colonists. In ancient times Chersonese was an important manufacturing and trade center as well as the political center of a city-state that encompassed the southwestern coast of the Crimea. The city flourished in the 4th-2nd century BC. It had a democratic system of government and coined its own money. Its economy was based on viticulture, fishing, manufacturing, and trade (grain, cattle, fish) with other Greek cities, the Scythians, and the Taurians. In the 1st century BC Chersonese recognized the sovereignty of Prince Mithradates VI of the Bosporan Kingdom and, later, of Rome. At the end of the 4th century AD the city became part of the Byzantine Empire. In the 5th-11th century it was the largest city on the northern coast of the Black Sea and an important center of Byzantine culture. At the end of the 10th century Chersonese was captured and held briefly by Prince Volodymyr the Great. From that point on Byzantine cultural influences often entered Kyivan Rus' through Chersonese... |

| Chersonese Taurica |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

IV. THE KYIVAN RUS' STATE AND ITS UKRAINIAN PRINCIPALITIES

IV. THE KYIVAN RUS' STATE AND ITS UKRAINIAN PRINCIPALITIES

In the 9th century the Varangians from Scandinavia conquered the proto-Slavic tribes on the territory of today's Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia and laid the groundwork for the Kyivan Rus? state. Kyiv became the centre and capital of the new realm. The first period of Kyivan Rus? history can be characterized as the era of expansion, which saw Kyiv extend its authority over all of the east-Slavic tribes. The second period, associated primarily with the reigns of Volodymyr the Great and Yaroslav the Wise, was the era of internal consolidation as a result of which Kyivan Rus? became one of the pre-eminent states of Europe. The internecine wars between Rus' princes, which began after the death of Yaroslav the Wise, led to the political fragmentation of the state into a number of principalities. In the Ukrainian lands, the Kyiv principality, Turiv-Pynsk principality, Volodymyr-Volynskyi principality, Halych principality, Chernihiv principality, and Pereiaslav principality emerged as independent and separate entities, with their own political and economic peculiarities. The quarreling between the princes left Rus? vulnerable to foreign attacks, and the invasion of the Mongols in 1236?40 finally destroyed the state... Learn more about the Kyivan Rus' state and its Ukrainian principalities by visiting the following entries:

|

KYIVAN RUS'. The first state to arise among the Eastern Slavs. It took its name from the city of Kyiv, the seat of the grand prince from about 880 until the beginning of the 13th century. At its zenith, it covered a territory stretching from the Carpathian Mountains to the Volga River, and from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea. The state's rapid rise and development was based on its advantageous location at the intersection of major north-south and east-west land and water trade routes with access to two major seas, and favorable local conditions for the development of agriculture. In the end, however, the state's great size led to the development of centrifugal tendencies and local interests that limited its political and social cohesion. This, and its proximity to the Asian steppes, which left it vulnerable to invasions of nomadic hordes, eventually contributed to the decline of Kyivan Rus'... |

| Kyivan Rus' |

|

KYIV PRINCIPALITY. The central principality in Kyivan Rus?. It was formed in the mid-9th century and existed as an independent entity until the mid-12th century, when it became an appanage principality. Its basic territory consisted of the area of Right-Bank Ukraine inhabited by the tribes of Polianians and Derevlianians. The Prypiat River usually formed the northern boundary, the Dnieper River the eastern, and the Sluch River and Horyn River the western. The southern boundary was the most dynamic; at times it was as far south as the southern Boh River and Ros River, while at other times (end of the 11th century) it stopped at the Stuhna River. Kyiv, the capital of the principality, lay on the crossroads of the trade routes from north to south and east to west that joined Asia to Europe. This favorable location fostered the development of trade and the principality's prosperity. The oldest cities were Kyiv, Vyshhorod, Ovruch, and Bilhorod... |

| Kyiv principality |

|

CHERNIHIV PRINCIPALITY. One of the largest and mightiest political entities of Kyivan Rus? in the 11th-13th century. The principality was formed in the 10th century and retained some of its distinctiveness until the 16th century. Its basic territory consisted of the basins of the Desna River and Seim River in Left-Bank Ukraine, which were settled by the Siverianians and partly by the Polianians in the south. Eventually the principality expanded to encompass the territory of the Radimichians and some of the lands settled by the Viatichians and Drehovichians. Chernihiv was the capital of the principality, which included a number of towns and cities, such as Novhorod-Siverskyi, Starodub, Briansk, Putyvl, Kursk, Liubech, Hlukhiv, Chechersk, Kozelsk, Homel, and Vyr. Until the 12th century the domain and influence of the principality expanded far into the northeast (the Murom-Riazan land) and into the southeast (Tmutorokan principality)... |

| Chernihiv principality |

|

PEREIASLAV PRINCIPALITY. In his will Prince Yaroslav the Wise designated an appanage principality with its capital in Pereiaslav and bequeathed it to his son, Vsevolod Yaroslavych, who ruled it from 1054. When Vsevolod ascended the Kyivan throne in 1078, he continued ruling Pereiaslav principality as well. While it was independent, the principality bordered on Kyiv principality along the Dnieper River and the Desna River to the west, and was separated from Chernihiv principality to the north and northeast by the Oster River, the inaccessible marshes of the Smolynka River, and the Romen River and the Sula River. Until the first half of the 12th century the principality also controlled the Seim region as far east as Kursk. Its southern and eastern borders reached at times as far as the Sosna River, a right tributary of the Don River, but fluctuated because of constant incursions of the Pechenegs, Torks, and Cumans... |

| Pereiaslav principality |

|

VOLODYMYR-VOLYNSKYI PRINCIPALITY. A principality of medieval Kyivan Rus?, covering the upper and middle reaches of the Buh River and the tributaries of the Prypiat River. It was formed in the 10th century out of territories inhabited by the Volhynians. Vsevolod, the son of Volodymyr the Great, was its first ruler. The Liubech congress of princes in 1097 awarded the principality to Davyd Ihorovych, and the Vytychiv congress of princes in 1100 overturned that decision in favor of Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych. Volodymyr Monomakh seized the territory and placed it under his son, Andrii. Then it was ruled by Iziaslav Mstyslavych for two decades. After his death the principality was divided among his sons, and became independent of Kyiv. Volodymyr-Volynskyi principality reached its apex under Roman Mstyslavych (1170-1205), who merged the principality with Halych principality in 1199, thereby creating the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia... |

| Volodymyr-Volynskyi principality |

|

HALYCH PRINCIPALITY. A principality of medieval Kyivan Rus? that emerged in the mid 12th century. Prince Volodymyrko Volodarovych, who inherited the Zvenyhorod principality in 1124, the Peremyshl principality in 1129, and the Terebovlia principality and Halych land in 1141, established his capital in princely Halych in 1144. Volodymyrko's son, Yaroslav Osmomysl, the pre-eminent prince of the Rostyslavych house, enlarged Halych principality during his reign (1153-87) to encompass all the lands between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dniester River as far south as the lower Danube River. Trade and salt mining stimulated the rise of a powerful boyar estate in Galicia. When Volodymyr Yaroslavych, the last prince of the Rostyslavych house, died in 1199, the boyars invited Prince Roman Mstyslavych of Volhynia to take the throne. Roman Mstyslavych united Galicia with Volhynia and thus created the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia... |

| Halych principality |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with the history of Kyivan Rus' and its Ukrainian principalities were made possible by a generous donation from BOHDAN AND ALEXANDRA BULCHAK of Toronto, ON, Canada.

V. VOLODYMYR THE GREAT AND THE CHRISTIANIZATION OF RUS'-UKRAINE

V. VOLODYMYR THE GREAT AND THE CHRISTIANIZATION OF RUS'-UKRAINE

Over the 35 years of his rule, Grand Prince Volodymyr of Kyiv expanded the borders of Kyivan Rus' and turned it into one of the most powerful states in Eastern Europe. He conquered and united the East Slavic tribes, divided his realm into lands, and installed his sons or viceroys to govern them. Initially he attributed his victories to the support he received from pagan deities. Later he became convinced that a monotheistic religion would consolidate his power, as Christianity and Islam had done for neighboring rulers. His choice was determined after the Byzantine emperor Basil II turned to him for help in defeating his rival. Volodymyr offered military aid only if he was allowed to marry Basil's sister, and Basil agreed to the marriage only after Volodymyr promised to convert himself and his subjects to Christianity. Volodymyr and his family were baptized in December 987. The mass baptism of the citizens of Kyiv took place on 1 August 988, and the remaining population of Rus' was slowly converted, sometimes by force. The adoption of Christianity as the official religion facilitated the unification of the Rus' tribes and the establishment of foreign dynastic, political, cultural, religious, and commercial relations, particularly with the Byzantine Empire, Bulgaria, and Germany... Learn more about Volodymyr the Great and the Christianization of Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

|

VOLODYMYR THE GREAT (Valdamar, Volodimer, Vladimir), b ca 956, d 15 July 1015 in Vyshhorod, near Kyiv. Grand prince of Kyiv from 980; son of Sviatoslav I Ihorovych and Malusha; half-brother of Yaropolk I Sviatoslavych and Oleh Sviatoslavych; and father of 11 princes by five wives, including Sviatopolk I, Yaroslav the Wise, Mstyslav Volodymyrovych, and Saints Borys and Hlib. In 969 Grand Prince Sviatoslav I named Volodymyr the prince of Novgorod, where the latter ruled under the guidance of his uncle, Dobrynia. In 977 a struggle for power broke out among Sviatoslav's sons. Yaropolk seized the Derevlianian land and Novgorod, thereby forcing Volodymyr to flee to Scandinavia. In 980 Volodymyr returned to Rus' with a Varangian force, expelled Yaropolk's governors from Novgorod and took Polatsk. Later that year he captured Kyiv and had Yaropolk murdered, thereby becoming the grand prince... |

| Volodymyr the Great |

|

CHRISTIANIZATION OF UKRAINE. Christianity was known on the present territory of Ukraine as early as the first century AD. At first Christianity won converts among the Greek colonists who settled the northern coasts of the Black Sea. The Primary Chronicle mentions Saint Andrew's mission on the Black Sea coast at Synope and his blessing of present-day Kyiv. According to traditional belief the popes Saint Clement I (90-100) and Saint Martin (649-55) were exiled to the Crimea. The proximity of the Slav-settled lands to the Greek colonies on the Black Sea must have been an important factor in the spread of Christianity among the Slavic tribes. More concrete data on the presence of Christianity on Ukrainian territories extend back to the 3rd century, when the Goths invaded these territories from the north. At first the Goths destroyed the Christian colonies and then conducted forays into Asia Minor, bringing back slaves from as far away as Cappadocia. These slaves acquainted the Goths with Christianity... |

| Christianization of Ukraine |

|

PRINCESS OLHA (Olga), b ca 890, d 11 July 969 in Kyiv. Kyivan Rus' princess and Orthodox saint; wife of Prince Ihor and mother of Sviatoslav I Ihorovych. Olha was Sviatoslav's regent during his minority (945-57) and his later military campaigns. After Ihor's death she subdued the rebellious Derevlianians and avenged his slaying. She expanded and strengthened the central power of Kyiv. In foreign affairs she was mainly concerned with political relations with Constantinople. Olha was the first Kyivan Rus' ruler to become a Christian. Olha urged Sviatoslav to become a Christian, but he remained a pagan. He allowed a Christian community to develop in Kyiv, however, thereby paving the way for the Christianization of Ukraine by his son and Olha's grandson, Volodymyr the Great.... |

| Princess Olha |

|

BYZANTINE EMPIRE. Byzantium was originally a Greek colony, founded ca 660 BC on the European side of the Bosporus. In 326 Constantinople was built on the site of Byzantium, and in 330 the city became the capital of the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire, which endured until 1453 and played an important role in the history of Eastern Europe and the Near East. Byzantine chronicles mention Rus' attacks in about 842 and a Rus' siege of Constantinople in 860. In the 10th century relations between Rus' and Byzantium intensified. The Christianization of Ukraine was facilitated by the trade between Rus' and Byzantium, conducted along the Varangian route, and by the Byzantine colonies on the northern coast of the Black Sea. With Volodymyr the Great's adoption of Christianity in 988-9 Ukraine came under Byzantine religious influence. Like other southeastern European nations it inherited from Byzantium not only the Christian faith but also its culture... |

| Byzantine Empire |

|

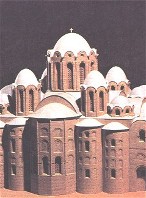

CHURCH OF THE TITHES (Desiatynna tserkva). The first and largest stone church in Kyiv and the burial place of the Kyivan princes. Dedicated to the Dormition, it was built by Byzantine and Rus' artisans between 989 and 996 amid the palaces of Grand Prince Volodymyr the Great, who set aside a tithe of his income for its construction and maintenance (hence the name). The church was besieged and ruined in 1240 by Batu Khan's Mongol horde. Excavations of the foundations indicate that it was a three-nave structure with six pillars and wide, covered galleries on the sides. It occupied an area of approx 1,700 sq m. Its numerous cupolas in cruciform arrangement distinguished it from Byzantine prototypes and made it a model in the further development of Ukrainian architecture... |

| Church of the Tithes |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with Volodymyr the Great and the Chtistianization of Rus'-Ukraine were made possible by a generous donation from ARKADI MULAK-YATSKIVSKY of Los Angeles, CA, USA.

VI. KYIVAN RUS' 1015-1132: FROM YAROSLAV THE WISE TO MSTYSLAV THE GREAT

VI. KYIVAN RUS' 1015-1132: FROM YAROSLAV THE WISE TO MSTYSLAV THE GREAT

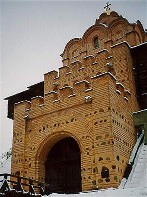

After Volodymyr the Great's death in 1015, his son Sviatopolk I seized power, but he was opposed in a bitter internecine war and was eventually defeated by Yaroslav the Wise. Yaroslav shared power with his half-brother Mstyslav until Mstyslav died in 1036. Yaroslav's reign as unchallenged grand prince (1036-54) was one of the highest points in the history of Kyivan Rus'. The process of internal consolidation begun earlier was greatly furthered by Yaroslav's codification of the law in Ruskaia Pravda. Culture flourished: the magnificent Saint Sophia Cathedral was built in Kyiv, the Kyivan Cave Monastery was founded, a library was established, and learning and education were encouraged. Yaroslav also appointed the first local hierarch as Kyivan metropolitan (Metropolitan Ilarion), thus asserting Kyiv's independence of Constantinople. Yaroslav's death initiated another round of civil war and internecine struggle, although he had tried to prevent this effect by preparing a plan for dividing up political power between his sons. The situation was further complicated by the presence of the Cumans who for the next century and a half waged continuous war against Rus' and became involved in the internecine wars, serving as allies of one branch of the dynasty or another. A brief respite occurred during the reign of Volodymyr Monomakh (1113-25). Under him Kyiv once again flourished and the internecine wars abated. Ruskaia Pravda was amended and several valuable works of literature, hagiography, and historiography were composed, including the important Kyivan Cave Patericon. Volodymyr's son Mstyslav I Volodymyrovych (1125-32) was the last grand prince of Kyiv who controlled almost the entire territory of the Rus' state. After his death, the Kyivan Rus' federation continued to disintegrate and Kyiv itself gradually lost its primacy... Learn more about Kyivan Rus' state from Yaroslav the Wise to Mstyslav the Great by visiting the following entries:

|

YAROSLAV THE WISE, b 978, d 20 February 1054 in Kyiv. Grand prince of Kyiv from 1019; son of Volodymyr the Great; father of seven princes, including Iziaslav Yaroslavych, Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych, and Vsevolod Yaroslavych. After the death of Volodymyr, Yaroslav waged war against his brother Sviatopolk I for the Kyivan throne which he eventually assumed in 1019. His half-brother Mstyslav Volodymyrovych of Tmutorokan and Chernihiv, who was vying for control of southern Rus', proved to be a more stubborn opponent, and Yaroslav was forced to cede to Mstyslav all of Left-Bank Ukraine except Pereiaslav principality. After Mstyslav's death in 1036, Yaroslav annexed his lands and became the unchallenged ruler of Kyivan Rus'. During his reign, Kyiv and other Rus' cities were considerably transformed. Over 400 churches were built in Kyiv alone, which was turned into an architectural rival of Constantinople. To strengthen his power and provide order in social and legal relations in his realm, Yaroslav arranged for the compilation of a book of laws called 'Pravda Iaroslava' (Yaroslav's Justice), the oldest part of the Ruskaia Pravda... |

| Yaroslav the Wise |

|

IZIASLAV YAROSLAVYCH, b 1024, d 3 October 1078. Grand prince of Kyiv intermittently from 1054 to 1078; the eldest son of Yaroslav the Wise. Before inheriting the throne of Kyiv from his father, Iziaslav ruled Turiv. In the 1060s he brought most of the Rus' territories west of the Dnieper River under his control. For refusing them arms to fight invading Cumans, the inhabitants of Kyiv revolted in 1068. He fled to Poland and with the aid of his brother-in-law and cousin, Boleslaw II the Bold, took Kyiv a year later from Vseslav Briachislavich of Polatsk. When his brothers Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych and Vsevolod Yaroslavych of Chernihiv marched on Kyiv in 1073, its inhabitants refused to support Iziaslav Yaroslavych and he was forced to flee abroad. He sought help in 1075 from Emperor Henry IV of Germany and Pope Gregory VII, but his efforts were in vain. In 1077, after Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych, who ruled Kyiv, died and was succeeded by Vsevolod Yaroslavych, Iziaslav Yaroslavych marched on Kyiv with Polish troops. Vsevolod renounced his throne and retired to Chernihiv. Iziaslav died in battle helping Vsevolod recapture Chernihiv from Oleh Sviatoslavych and his Cuman allies... |

| Iziaslav Yaroslavych |

|

SVIATOSLAV II YAROSLAVYCH, b 1027, d 27 December 1076 in Kyiv. Kyivan Rus' prince; son of Yaroslav the Wise. Sviatoslav ruled in Volodymyr-Volynskyi while his father was alive and then became prince of Chernihiv (from 1054). At first the three oldest sons of Yaroslav ruled in harmony; together with Vsevolod Yaroslavych, the prince of Pereiaslav, and Iziaslav Yaroslavych, the grand prince of Kyiv, Sviatoslav defeated the Torks in 1060 and Vseslav Briachislavych, the prince of Polatsk, in 1067. In 1068 he and his brothers took some losses from the Cumans on the Alta River near Pereiaslav, but later that year he himself won a significant victory over the Cuman forces on the Snov River in Chernihiv principality. With Vsevolod's help Sviatoslav deposed Iziaslav on 22 March 1073 and took over as grand prince of Kyiv. During his rule the territory of Kyivan Rus' was greatly increased. He was a patron of education, and he sponsored the compilation of Izbornik of Sviatoslav (1073) and Izbornik of Sviatoslav (1076), which had a great influence on the further development of educational literature in Kyivan Rus'... |

| Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych |

|

VSEVOLOD YAROSLAVYCH, b 1030, d 13 April 1093. Kyivan Rus' prince; fifth (and favorite) son of Yaroslav the Wise and father of Volodymyr Monomakh. After his father's death in 1054, Vsevolod received Pereiaslav and other principalities and for nearly two decades maintained the peace of the realm through close co-operation with his elder brothers, Iziaslav and Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych. One of the crowning achievements of that period was the confirmation in 1072 of the so-called 'Pravda Iaroslavychiv', an extensive revision of their father's law codes. Fighting between the princes started in 1073, when Vsevolod rose up against Iziaslav at Sviatoslav's bidding. Iziaslav then fled abroad, Sviatoslav emerged as the grand prince of Kyiv, and Vsevolod took the throne of Chernihiv. Upon Sviatoslav's death in 1077, Iziaslav returned to Kyiv, but he died the following year and Vsevolod ascended the Kyivan throne in 1078. The remainder of his reign saw continued fighting among the Kyivan Rus' princes, but also considerable artistic and cultural development, including the building of the Vydubychi Monastery near Kyiv... |

| Vsevolod Yaroslavych |

|

VOLODYMYR MONOMAKH, b 1053, d 19 May 1125 in Kyiv. Grand prince of Kyiv (1113-25); son of Vsevolod Yaroslavych. He was named Monomakh after his mother, who was the daughter of the Byzantine emperor Constantine Monomachos. While his father was alive, Volodymyr ruled the Smolensk principality (from 1067) and Chernihiv principality (1078-94), and led 13 successful military campaigns in his father's name. He became prince of Pereiaslav in 1094. After the death of Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, he ascended to the Kyivan throne. Volodymyr was one of the outstanding statesmen of the medieval period in Ukraine. He sought to strengthen the unity of Rus' and the central authority of the Kyivan prince. He struggled against the deterioration of dynastic solidarity in Kyiv and attempted to unite the princes against the Cuman threat. During his tenure in Kyiv, he introduced a number of legal and economic reform, issued Volodymyr Monomakh's Statute (which was added to Ruskaia Pravda), and was the author of Poucheniie ditiam (Instruction for [My] Children, ca 1117), which was entered into the Laurentian Chronicle... |

| Volodymyr Monomakh |

|

MSTYSLAV VOLODYMYROVYCH THE GREAT, b 5 June 1076 in Turiv, d 20 April 1132 in Kyiv. Grand prince of Kyiv from 1125; eldest son of Volodymyr Monomakh and Gytha, daughter of Harold II of England; brother of Yaropolk II Volodymyrovych, Viacheslav Volodymyrovych, and Yurii Dolgorukii. As prince of Novgorod (1088-93, 1095-1117) and Rostov and Smolensk (1093-5) Mstyslav took part in the 1093, 1107, and 1111 Rus' campaigns against the Cumans. From 1117 to 1125 Mstyslav was prince of Bilhorod, near Kyiv, and co-ruled his father's realm. After Volodymyr Monomakh's death in May 1125, he ascended the Kyivan throne. With the help of his six sons, his brothers, and his cousins he controlled virtually all of Kyivan Rus'. Continuing the Riurykide dynasty's tradition of dynastic ties he married as his first wife Kristina, the daughter of King Ingi of Sweden. He gave his daughter Malfrid in marriage to King Sigurd I of Norway, his daughter Ingeborg to the Danish duke Knud Lavard, and his daughter Iryna Dobrodeia to the Byzantine prince (later emperor) Andronicus I Comnenus... |

| Mstyslav Volodymyrovych the Great |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with Kyivan Rus' from Yaroslav the Wise to Mstyslav the Great were made possible by a generous donation from ARKADI MULAK-YATSKIVSKY of Los Angeles, CA, USA.

VII. THE MEDIEVAL PRINCIPALITY OF GALICIA-VOLHYNIA

VII. THE MEDIEVAL PRINCIPALITY OF GALICIA-VOLHYNIA

After the death of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kyiv in 1054, the polity of Kyivan Rus' that he ruled came to be divided into 5 and then into 13 separate principalities. With time, the internecine wars over Kyiv that continued between the Rus' princes throughout most of the 12th century greatly undermined Kyiv's importance and its primacy in Rus'. At the same time, western-Ukrainian principalities of Halych (Galicia) and Volodymyr (Volhynia) gained prominence. Galicia assumed the leading role among the Ukrainian principalities during the reigns of Prince Volodymyrko Volodarovych (1124-53) and his son Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153-87) who extended the territory of Halych principality to the Danube River Delta. Volhynia gained high stature in the 1120s, but became even more important at the end of the 12th century after all of its minor principalities were reunited under the rule of Prince Roman Mstyslavych (1173-1205). In 1199 Roman was invited by the Halych boyars to become the ruler of Halych principality and as a result, a powerful state was created in western Rus': the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Following a period of boyar rebellions in the first decades of the 13th century, Roman's son, Danylo, consolidated his control of Galicia and Volhynia in the 1240s. He also took the Rus' territories occupied by Lithuania in the north and extended his rule beyond Kyiv in the east. However, after the enormous destruction wreaked by the Mongol invasion of Rus' in 1239-41, Danylo Romanovych was forced to pledge allegiance to Batu Khan of the Golden Horde. Nonetheless, his Principality of Galicia-Volhynia retained a considerable degree of independence even after the destruction of other Rus' principalities on Ukrainian territories. His policies were continued by his son Lev Danylovych and other members of the Romanovych dynasty. The death of the last Ukrainian prince of Galicia-Volhynia, Yurii II Boleslav, in 1340 marks the end of the Princely era in the history of Ukraine... Learn more about the history of medieval Principality of Galicia-Volhynia by visiting the following entries:

|

ROMAN MSTYSLAVYCH, b ca 1160, d 14 October 1205 in Zawichost, Poland. Rus' prince, founder of the Romanovych dynasty; son of Mstyslav Iziaslavych and Agnesa (daughter of Prince Boles?aw Krzywousty of Poland). When his father died Roman was bequeathed the Volodymyr principality (1170). He soon managed to consolidate his power in Volhynia by taking control of appanage principalities of Lutsk and Berestia. After the death in 1199 of the last prince of the Rostyslavych house of Halych, Roman ascended to the Halych throne and united Galicia and Volhynia into the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. An able political and military leader, he brought the restive boyars to heel and cultivated the support of the burghers. He waged two successful campaigns against the Cumans, in 1201-2 and 1203-4, from which he returned with rescued captives. In 1204 he captured Kyiv and thus became the most powerful of all the Rus' princes of that time. He played an active role in the political affairs of foreign states: Poland, Hungary, Byzantium, Lithuania, and Germany. Roman died at the height of his political influence at the Battle of Zawichost, after he was ambushed by the Poles. He was described by a contemporary chronicler as a 'grand prince, the sole ruler of all Rus', who conquered the pagans and wisely adhered to the commandments of God...'

|

| Roman Mstyslavych |

|

PRINCIPALITY OF GALICIA-VOLHYNIA. A state founded in 1199 by Prince Roman Mstyslavych of Volhynia who assumed the throne of princely Halych and united Galicia and Volhynia under his rule. In 1202 Roman captured Kyiv with its domains up to the Dnipro River, thereby creating a powerful state in western Rus'. But after Roman's death in 1205 interminable boyar rebellions arose, which were exploited by Poland and Hungary; these rebellions and wars lasted until 1238, when Roman's son, Danylo, having consolidated his rule in Volhynia, finally seized Galicia. After subduing the boyars in 1241-2 and defeating the Chernihiv princes and their Polish and Hungarian allies at the Battle of Yaroslav in 1245, Danylo gained full control of Galicia-Volhynia. He also conquered lands in the north from Lithuania and extended his rule beyond Kyiv in the east. Because of Danylo's close alliance with his brother Vasylko Romanovych, who ruled Volodymyr-Volynskyi from 1241 to 1269, the Galician-Volhynian state attained the apex of its power during his reign. But after the destructive Mongol invasion in 1239-41, Danylo was forced to pledge allegiance to Batu Khan of the Golden Horde in 1246. He strove, however, to rid his realm of the Mongol yoke by attempting, unsuccessfully, to establish military alliances with other European rulers. During Danylo's reign the cities of Lviv and Kholm were founded... |

| Principality of Galicia-Volhynia |

_s.jpg)

|

DANYLO ROMANOVYCH, b 1201, d 1264 in Kholm. Prince of Galicia-Volhynia, king of Rus' (from 1253). After the death of his father, Roman Mstyslavych, in 1205, unrest among the Halych boyars forced Danylo to take refuge at the Hungarian court, and later, with his mother and brother, Vasylko Romanovych, in small principalities in Volhynia. Following a long struggle with neighboring princes and Galician boyars (1219-27) Danylo finally united Volhynia under his rule. In 1238 he gained control of Halych, and in 1239 he took Kyiv. However, the Mongol invasion of 1240-1, during which Kyiv, Volodymyr, and Halych were destroyed, interfered with Danylo's plans for the unification of Ukrainian territories. He was nevertheless able, to defeat a coalition of the Chernihiv princes, disaffected boyars, and their Hungarian and Polish allies in 1245 and establish full control over Galicia. In order to save his state, Danylo was compelled to recognize the khan's suzerainty, but he prepared to overthrow his Mongol overlords. To get the support of the pope, Danylo agreed to acknowledge him as head of the church in his principalities and accepted a crown from him in 1253. Under his reign Western European cultural influences were strong in Ukraine, and Western European political and administrative forms took hold, particularly in the towns. After the Mongols razed Halych in 1241, Danylo established Kholm as the new capital of his state... |

| Danylo Romanovych |

|

KHOLM (Polish: Chelm). The principal city of the Kholm region, situated on the steep bank of the Uherka River, a tributary of the Buh River; from 1975 to 1999 the capital of Che?m voivodeship in Poland, currently a city in Lublin voivodeship. The date of its origin is unknown. In 1237 Prince Danylo Romanovych of Volhynia built a castle there and reinforced the town with stone walls and with defensive towers in the neighboring villages of Bilavyne and Stolpie. As a result Kholm withstood the Mongol invasion of 1240. At that time the trade route linking Kyivan Rus' via Galicia with the Mediterranean lost its importance because of Constantinople's decline and the Mongols' control of the steppes and was supplanted by the route linking western Rus' via the Buh River and the Vistula River with the Baltic Sea ports and the realm of the Teutonic Knights. Because Kholm was located on the latter route, after becoming the ruler of the Galicia, Danylo made it his capital and the see of Kholm eparchy. Starting in the 1250s he constructed a formidable fortress in Kholm and transformed the city into a vital commercial and cultural center. As the capital of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (until 1272) and then of an appanage Kholm principality, the town withstood another Mongol siege (1261) but suffered greatly during the Lithuanian-Polish-Hungarian wars for control of Galicia-Volhynia in the 14th century before being annexed by Poland in 1387... |

| Kholm |

|

LEV DANYLOVYCH, b ca 1228, d ca 1301. Prince of Peremyshl (1240-69), Belz (1245-69), and Galicia (1264-1301); son of King Danylo Romanovych. He had dynastic ties with Hungary through his marriage to Konstancia, the daughter of King Bela IV. Lev inherited the Halych pincipality as well as the Peremyshl and Belz lands from his father in 1264 and became the most powerful ruler of the Romanovych dynasty in western Rus'. In 1268 he murdered the Lithuanian prince Vaisvilkas after Vaisvilkas abdicated and gave Lithuania to his son-in-law, Shvarno Danylovych, instead of to Lev. As a result Lev spoiled the plans for the unification of Galicia-Volhynia and Lithuania under the rule of a prince from a Rus' dynasty. Lev inherited the Kholm land and Dorohychyn land after Shvarno's death ca 1269. He made Lviv (which was named after Lev) his capital in 1272. A vassal of the Tatars from the early 1270s, he had their support during his campaigns against Lithuania (1275, 1277), Poland (1280, 1283, 1286-8), and Hungary (1285). He made a pact with Wenceslas II of Bohemia in 1279 and, as his ally, tried unsuccessfully to seize Cracow in 1280. Lev's long war with Poland brought little gain. He annexed to his realm part of Transcarpathia (including Mukachevo) ca 1280 and part of the Lublin land ca 1292. Lev Danylovych gained a general reputation as a brave military commander, but a rather short-sighted and impulsive politician... |

| Lev Danylovych |

|

YURII II BOLESLAV, b ca 1306, d 7 April 1340 in Volodymyr-Volynskyi. Last ruler of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (1323-40); son of Prince Trojden II of Mazovia and grandson of Prince Yurii Lvovych, thus a member of both the Polish Piast dynasty and the Rus' Romanovych dynasty. He was initially known as Boles?aw and raised as a Catholic. He converted to Orthodoxy, evidently in connection to his candidacy for the throne of Galicia-Volhynia, assumed the name Iurii, and ascended to the princely seat of Volodymyr-Volynskyi principality. He maintained friendly relations with Lithuania (he married Yevfymiia-Ofka, daughter of the grand duke of Lithuania, Gediminas) and the Teutonic Knights, with whom he signed treaties in 1325, 1327, 1334, 1335, and 1337. He was met with hostility by Poland and Hungary, however. Yurii sought to strengthen his rule by supporting towns and burghers, protecting German colonists, and encouraging the influx of foreigners. Under his rule Sianik was granted rights under Magdeburg law. The Galician and Volhynian boyars rebelled against him, and he was poisoned in suspicious circumstances. His death marked the end of the Romanovych dynasty of Galician-Volhynian princes as well as the end of the Princely era of Ukraine... |

| Yurii II Boleslav |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the history of medieval Principality of Galicia-Volhynia were made possible by the financial support of the SENIOR CITIZENS HOME OF TARAS H. SHEVCHENKO (WINDSOR) INC. FUND at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

VIII. UKRAINE IN 14th-16th CENTURIES: THE LITHUANIAN-RUTHENIAN STATE

VIII. UKRAINE IN 14th-16th CENTURIES: THE LITHUANIAN-RUTHENIAN STATE

Following the destruction of the Kyivan Rus' state by the Mongol invasion in the 13th century and the subsequent demise of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia which was conquered by Poland in the mid 14th century, the majority of Ukrainian lands progressively came under the control of the grand dukes of Lithuania. Weakened by Tatar attacks and internal strife, the Ukrainian princes offered little resistance to Lithuanian hegemony and joined its administrative system. Lithuanian southward expansion reached its peak during the reign of Grand Duke Algirdas (ruled 1345-77) who succeeded in unifying all of the Belarusian and most of the Ukrainian territories in what many scholars have referred to as the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state. During the height of its expansion this state included nearly half of the former territory of Kyivan Rus'. Since only 10 percent of the realm was inhabited by Lithuanians, the official culture, language, law code, and religion of the new state became Ruthenian (ie, Ukrainian-Belarusian). As members of the grand duke's privy council, high-ranking military commanders, and administrators, Ruthenian nobles (such as the Olelkovych family) became part of the ruling elite. Ruthenian became the official state language and Orthodoxy the prevailing religion (10 of Algirdas's 12 sons were Orthodox). Under Algirdas's son and successor Jogaila, the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state was threatened by the Teutonic Knights, Tatars, and Muscovy. To gain support Jogaila agreed to marry the Polish queen Jadwiga, share her throne, and unite Lithuania with Poland. Opposition to this union was led by Vytautas the Great, whose popularity forced Jagiello to recognize him as grand duke of all Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands. Under his rule (1392-1430) the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state incorporated all the lands between the Dnister River and Dnieper River as far south as the Black Sea and reached the summit of its greatness. However, after his defeat by the Tatars in battle at the Vorskla River in 1399, Vytautas was forced to abandon his expansionist plans in the east and seek union with Poland. The Lithuanian-Polish Union of Horodlo of 1413 curtailed the participation of the Orthodox (and thus the Ruthenians) in governing the state and allowed only Catholics to remain in the Lithuanian state council. These processes were concluded in 1569 by the Union of Lublin after which almost all Ukrainian territories came under Polish control and the Lithuanian-Ruthenian period came to an end... Learn more about the history of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state of the 13th to 16th centuries by visiting the following entries:

|

LITHUANIAN-RUTHENIAN STATE. A feudal state of the 13th to 16th centuries that included Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian lands. Each of its constituent principalities enjoyed a wide-ranging autonomy. The ruler was the grand duke, who was assisted by a boyars' council. From 1323 the capital was Vilnius. Lithuania began to encroach on Ukrainian and Belarusian territories during the reign of its founder, Mindaugas (1236-63). Gediminas (1316-41) and his son, Algirdas (1345-77), annexed the Pynsk region, Berestia land and the lans of the Chernihiv principality, Siversk principality, Podilia, Pereiaslav principality, and Kyiv principality. Political and cultural life in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state was based on the traditions of the Kyivan Rus' and Galician-Volhynian states. An official Ruthenian language evolved from the language used in Rus'. The legal system was based on the legal traditions of Kyivan Rus' (Ruskaia pravda and later the Lithuanian Statute). Dynastic ties between the princes of Rus' and Lithuania helped to maintain the Ruthenian influence. The Ruthenian princes belonged to the duke's councils and were part of the ruling class. The Orthodox church was allowed to develop freely, and it played an important role in the country's cultural and educational life. Manufacturing and trade developed rapidly in the cities and towns. The situation changed abruptly after 1385, when Jagiello (1377-92) concluded the Union of Krevo and assumed the Polish crown... |

| Lithuanian-Ruthenian state |

|

ALGIRDAS or Olgierd, b ca 1296, d May 1377. Prince of Krevo and Vitsebsk (1341-5) and grand duke of Lithuania (1345-77). With the assistance of his brother Kestutis, the prince of Samogitia, Algirdas unified the Lithuanian territories and waged war to enlarge his realm, making it one of the largest European states of his day. In 1345, after capturing Vilnius, Algirdas became the grand duke of Lithuania. Thereafter, he gradually annexed the larger part of the Ukrainian territories. At first, in about 1355, Algirdas won the Chernihiv land and Novhorod-Siverskyi land from the Golden Horde. In 1363 he defeated the Tatar army at a crucial battle at Syni Vody which, in practice, freed Ukraine from Tatar hegemony. He then annexed the Kyiv land and soon after he added Podilia and the Pereiaslav land to his domain. Algirdas waged a successful war over Volhynia against the Polish king Casimir III the Great and left him with only the Belz land and the Kholm region in Ukraine. Algirdas succeeded in unifying all of the Belarusian and most of the Ukrainian territories under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. His respect for Ukrainian culture and the Ukrainian church won him the loyalty of the Ukrainian people as well as of the Ukrainian princes and magnates, who helped to administer the state. Algirdas left some of the Ukrainian territories he annexed under the care of the Ukrainian princes of the Riurykide dynasty; others he granted to his relatives. During his reign the Ukrainian (Ruthenian) language became an official language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania...

|

| Algirdas |

|

LITHUANIAN-RUTHENIAN LAW. The system of law of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state or, more precisely, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which from the 14th to the 18th century included Lithuania, Belarus, and most of Ukraine (to the Union of Lublin in 1569). The Lithuanian-Ruthenian law was initially based on Ruskaia Pravda of the Kyivan Rus' state and later on the Lithuanian Statute as well as Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian customary law. The Lithuanian Statute, prepared on the basis of Ruskaia Pravda, was one of the most advanced legal codes of its time. It was published in the 16th century in three basic editions. The First or Old Lithuanian Statute, ratified by the diet in Vilnius in 1529, consisted of 243 articles (272 in the Slutsk redaction). The overriding concern of this code was to protect the interests of the state and nobility, especially the magnates. The Second Lithuanian Statute (367 articles in 14 sections), often called the Volhynian version because of the influence of the Volhynian nobility in its preparation, was ratified in 1566. It brought about major administrative-political reforms, such as the division of the country into counties, and especially expanded the privileges of the lower gentry by admitting it to the diet. The Third Lithuanian Statute, consisting of 488 articles in 14 sections, was compiled after the union of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with Poland in 1569 (Union of Lublin) and was ratified in 1588. In this edition many Polish concepts were introduced into the criminal and civil law... |

| Lithuanian-Ruthenian law |

|

LITHUANIAN METROPOLY. An Orthodox church province that existed in the 14th and 15th centuries within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was founded following the occupation of much of western Ukraine by Lithuania. When Metropolitan Maximos of Kyiv transferred his see to Vladimir-on-the-Kliazma, the Lithuanian princes Gediminas and, later, Algirdas demanded a separate metropoly, free of Suzdal-Muscovite control. The Patriarch of Constantinople agreed and consecrated Roman 'metropolitan of Lithuania and Volhynia' in 1355, with his see in Navahrudak (Belarus) and jurisdiction over the eprchies of Polatsk, Turiv, Volodymyr, Lutsk, Kholm, Halych, and Peremyshl. In 1371 the western eparchies of the metropoly were transferred to the renewed Halych metropoly. After Metropolitan Roman's death in 1361, the Patriarch of Constantinople failed to appoint his successor, but in 1376 Grand Duke Vytautas the Great succeeded in having Cyprian consecrated as metropolitan, who in 1389 assumed control over all eparchies of the Halych metropoly and Kyiv metropoly. He resided in Moscow, and had the title 'Metropolitan of all Rus'.' Metropolitan Cyprian's successor, however, was not accepted in the Lithuanian-controlled territories of Ukraine, and a synod of the bishops of Polatsk, Smolensk, Lutsk, Chernihiv, Volodymyr, Turiv, Peremyshl, and Kholm elected Gregory Tsamblak as metropolitan of Lithuania in 1415. After Tsamblak died in 1419, the Lithuanian eparchies once again came under the authority of Moscow... |

| Lithuanian metropoly |

|

OLELKOVYCH FAMILY. A family of Orthodox appanage princes in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state. They were descended from Volodymyr, the son of Grand Duke Algirdas of Lithuania. His son, Olelko Volodymyrovych, from whom the family name is derived, and grandson, Semen Olelkovych, were the last Ruthenian princes of Kyiv. Olelko Volodymyrovych sought to develop Kyiv principality into an autonomous entity. He fostered the development of the Ukrainian church and culture, and he strengthened the southern frontiers of his lands against Tatar attacks. His son, Semen Olelkovych, served as the representative of the Rus' population in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state and also sought to expand the autonomy of the Kyiv principality. He supported the Lithuanian opposition to the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiellonczyk. He was backed by Lithuanian and Ruthenian boyars in an unsuccessful bid for the Lithuanian throne. Olelko's other son, Mykhailo Olelkovych, became the prince of Slutsk principality in Belarus. When he did not succeed his late brother, Semen, as appanage prince and voivode of Kyiv, Mykhailo organized a conspiracy to assassinate Casimir IV, but the conspiracy was uncovered and he was executed for treason. Mykhailo's son, Semen (d 14 November 1505), was an unsuccessful candidate for the Lithuanian throne after the death of Casimir IV in 1492... |

| Olelkovych family |

|

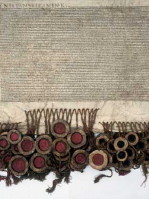

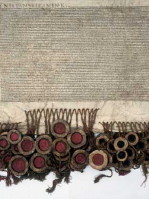

UNION OF LUBLIN. A union agreement between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, signed on 1 July 1569 at a joint assembly of Lithuanian and Polish deputies in Lublin. The treaty gave birth to a single state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with a common elected monarch combining the offices of the Polish king and the Lithuanian grand duke, a common diet and senate, a joint foreign policy, and one monetary system. The Grand Duchy preserved its autonomy with its own laws, government, administration, courts, army, and finances. The treaty was signed by Lithuania at a time when it needed Polish help in its war against Muscovy. For Poland the treaty provided a means of acquiring some Lithuanian territory. Under the treaty Poland (the Polish crown) obtained the Ukrainian territories of Podlachia, Volhynia, Podilia, the Bratslav region, and the Kyiv region. The nobility of those territories were given the same rights and privileges as the Polish nobility. The Grand Duchy retained, apart from Lithuanian territory, Belarus and the Berestia land and Pynsk region. Thus the union gave Poland control over a large part of Ukrainian territory, where it proceeded to subjugate and exploit the indigenous population. As a result of the Union of Lublin, the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state of the 13th to 16th centuries ceased to exist... |

| Union of Lublin |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the history of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state of the 13th to 16th centuries were made possible by the financial support of the TORONTO UKRAINIAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION of Toronto, ON, Canada.

IX. UKRAINE UNDER POLISH CONTROL IN THE POLISH-LITHUANIAN COMMONWEALTH IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

IX. UKRAINE UNDER POLISH CONTROL IN THE POLISH-LITHUANIAN COMMONWEALTH IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

With the Union of Lublin, signed on 1 July 1569, the Lithuanian-Ruthenian period in Ukrainian history came to an end. This treaty united Poland and Lithuania into a single Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita). In practical terms the union was dominated by the Poles, who now took direct control over most of Ukraine. The Polish influence on Ukraine was profound. Most of the Ukrainian nobles, granted equal rights with their Polish counterparts, were quickly Polonized, and Ukraine was thus bereft of its own social elite. The last vestiges of the Kyivan Rus' state disappeared as the Ukrainian lands were divided into six voivodeships, or provinces. Large tracts of land were granted to Polish nobles, who established sizable manorial estates (filvarky) that could produce effectively for the booming European grain trade. Some of the largest estates (latifundia) in the Commonwealth were situated in Ukraine. Greater demands were placed on the Ukrainian peasantry, which was being reduced to serfdom. The religious tolerance in the Commonwealth, phenomenal for its times, also had an impact in Ukraine, as the Reformation period saw the influence of Protestant groups, such as the Socinians and Lutherans, spread into Ukraine through Poland. Nevertheless pressure was put on the predominantly Orthodox population of Ukraine to convert to Catholicism, and it resulted indirectly in the establishment of the Ukrainian Catholic church by the Union of Berestia (1596). At the same time Ukraine experienced a tremendous revival. Theological and secular education, literature, and the fine arts all began to flourish, and printing was introduced. The ideas of the Renaissance began to work their way into Ukraine through Poland as the 'Golden Age' of 16th-century Polish culture left its mark. The situation in Ukraine under Polish rule became increasingly more volatile in the first half of the 17th century as socioeconomic, religious, and national tensions grew. These tensions peaked in 1648, when a full-scale uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky erupted in Ukraine and engulfed the Commonwealth in the Cossack-Polish War... Learn more about Ukraine under Polish control in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by visiting the following entries:

|

POLISH-LITHUANIAN COMMONWEALTH. Following the Union of Lublin in 1569, Poland and Lithuania constituted a single, federated state--the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth--ruled by a jointly elected monarch; the state was to have a common Diet, foreign policy, currency, and property law. Both partners were to retain separate administrations, law courts, treasuries, armies, and laws, however. Because Poland now possessed the larger territory, it had greater representation in the Diet and thus became the dominant partner. The only Ukrainian lands left in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were parts of the Berestia land and Pynsk region. Other Ukrainian lands constituted part of the Polish crown. There the Lithuanian Statute--the legal code of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state--remained in effect, but Ukrainian as the official language was supplanted by Polish and Latin. The integration of the Ukrainian lands into Poland resulted in significant national and religious transformations. Part of the Ukrainian elite became Polonized as a result of the influence of Polish education and in-migrating Polish nobles and Catholic clergy. Even many prominent Ukrainian families, including that of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, a leading defender of Orthodoxy, converted to Roman Catholicism and adopted Polish language and culture. Under the new regime, the noble-dominated cities and towns grew in size and number and experienced an economic boom. It was, however, almost exclusively the Catholic German and Polish burghers who benefited from self-government by Magdeburg law. The Orthodox Ukrainian burghers were the victims of persecution and segregation...

|

| Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth |

|

UNION OF LUBLIN. A union agreement between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, signed on 1 July 1569 at a joint assembly of Lithuanian and Polish deputies in Lublin. The treaty gave birth to a single state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with a common elected monarch combining the offices of the Polish king and the Lithuanian grand duke, a common diet and senate, a joint foreign policy, and one monetary system. Before the unon, during the height of its expansion, Lithuania's possessions included nearly half of the former territory of Kyivan Rus'. But the Union of Lublin was signed by Lithuania at a time when it needed Polish help in its war against Muscovy, and under the treaty, Lithuania ceded most of its Ukrainian lands to Poland. The Grand Duchy preserved its limited autonomy within the Commonwealth with its own laws, government, administration, courts, army, and finances. For Poland the treaty provided a means of acquiring much of Lithuanian territory. Under the treaty the Polish crown obtained the Ukrainian territories of Podlachia, Volhynia, Podilia, the Bratslav region, and the Kyiv region. The nobility of those territories were given the same rights and privileges as the Polish nobility. The Grand Duchy retained, apart from Lithuanian territory, Belarus and the Berestia land and Pynsk region. Thus the union gave Poland control over a large part of Ukrainian territory, where it proceeded to subjugate and exploit the indigenous population... |

| Union of Lublin |

_s.jpg)

|