Yiddish

Yiddish. A language based primarily on several Middle High German dialects with significant influences from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Romance and Slavic languages. It is written using a slightly modified Hebrew alphabet. The Yiddish spoken by Jews living in Ukrainian ethnolinguistic territory is clearly distinguished from the northeastern dialect (characteristic of Belarus, Lithuania, and Latvia) and the central dialect (characteristic of Poland and west Galicia).

Often referred to as the southeast dialect, Ukrainian Yiddish is profoundly marked by the influence of the Ukrainian language. In terms of grammar, for example, Yiddish shows evidence of a form of the Ukrainian aspect, which is absent from Middle High German (ikh hob geshribn ‘I have written’ versus ikh hob ongeshribn ‘I have completed writing’). Yiddish also has absorbed a multitude of Ukrainian conjunctions, prepositions, and adverbs, such as i ... i, take, nu ‘both ... and, indeed, well’. The rich variety of Ukrainian diminutives was adapted to Jewish names (eg, Moyshenyu, Khayimke, diminutive of Moyshe and Khayim), and Ukrainian names were sometimes given to Jewish children, particularly girls (eg, Badane, from Bohdana). The Yiddish vocabulary has also been enriched by countless Ukrainian words, such as khrayn (from Xrin, ‘horseradish’), zayde (from did, ‘grandfather’), and nudnik (from nudnyj, ‘boring’). Although several attempts have been made to classify the areas of human activity in which Ukrainian words penetrated Yiddish, the influence extended perhaps too widely to allow such classification, from the profane (paskudne, from paskudnyj ‘loathsome’) to the sacred (praven, from pravyty ‘to perform [a religious ceremony]’).

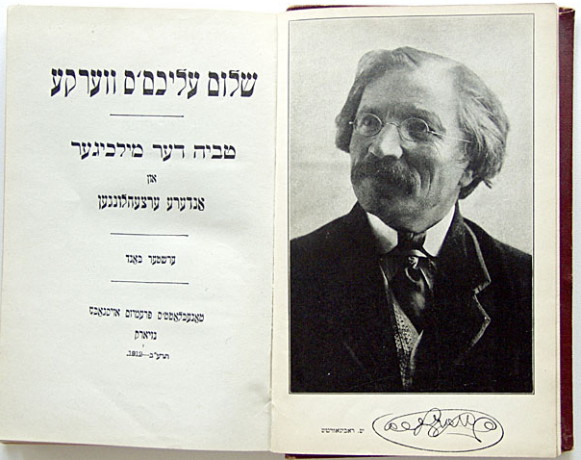

The flowering of Yiddish literature in Ukraine is exemplified by one of the greatest writers in this language, Sholom Aleichem (1859–1916). He legitimized the Ukrainian dialect by writing almost exclusively in that medium. The years he spent in the townlet of Voronkiv have been immortalized in his characters of the fictional Kasrilevke in Fiddler on the Roof.

With the establishment of Soviet Ukraine, Yiddish was made the official language of the Jewish proletariat to the exclusion of the classical Jewish language, Hebrew. A Yiddish press and theater briefly flourished in the 1920s, but the alphabet was ‘modernized’ by the removal of terminal forms of five letters, and great effort was expended to remove all Hebrew and Aramaic ‘bourgeois’ influences from Yiddish. Beginning in the 1930s, Yiddish was increasingly proscribed by Soviet authorities. With the loss of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Jews in the Holocaust, and the postwar harassment of Yiddish writers, Ukrainian Jewry turned increasingly to Ukrainian and Russian as vernacular languages. As a direct result of the most recent changes, a handbook of Yiddish (including rudiments of morphology, an anthology of literary work, short biographies of famous authors, and a brief history of Jews in Ukraine) was published in Kyiv in 1991.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Swoboda, V. ‘Ukrainian in the Slavic Element of Yiddish Vocabulary,’ HUS, 3–4 (1979–80)

Weinreich, M. History of the Yiddish Language, trans S. Noble (Chicago 1980)

Liptzin, S. A History of Yiddish Literature (New York 1985)

Henry Abramson

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993).]