Wedding

Wedding [весілля; vesillia]. The marriage ceremony with its accompanying festivities. In Ukraine the traditional wedding was a well-planned ritual drama, in which the leading roles were played by the bride and bridegroom, called princess and prince, and the other clearly defined roles (matchmaker, groomsman, bridesmaids) by the couple's parents, relatives, and friends. The wedding combined the basic forms of folk art—the spoken word, song, dance, music, and visual art—into a harmonious whole. It was reminiscent of an ancient theatrical drama with chorus, whose spectators were also actors. The rituals date back to pre-Christian times (traces of matriarchy, the abduction of the bride) and were influenced extensively by medieval practices (ransoming the bride, simulating a military campaign, the fighting between two camps, addressing the guests as princes and boyars, and the church ceremony). The ceremony included traces of ancient customs, which had lost their original, mainly magical, significance and had become mere play. Gradually the church ceremony assumed the central role in the wedding.

The traditional Ukrainian wedding usually took place in the early spring or the autumn and lasted several days. It was divided into many acts or episodes: (1) the matchmaking (svatannia)—discussions about the marriage between the bridegroom's representatives (starosty or svaty) and the bride's parents or relatives; (2) the inspection (ohliadyny, obzoryny, rozhliadyny)—a visit by the bride's relatives to the bridegrooms's house for the purpose of assessing his wealth; (3) the betrothal (zaruchyny, rukovyny, khustky)—the marriage agreement between the young couple, symbolized by the joining of hands; (4) the branch (hiltse viltse)—a ceremonious dressing of a green tree with flowers, ribbons, and ears of wheat; (5) the wreaths (vinky)—a ritual making of wreaths using periwinkle, the symbol of virginity; (6) the invitation (zaproshuvannia) of guests to the wedding; (7) the seating (posad) of the betrothed couple in the place of honor at the table; (8) the unbraiding (rozpleteny)—the ritual combing of the bride; (9) the wedding bread (korovai)—the baking and decorating of the ritual bread from flour donated by all the wedding participants; (10) the blessing (blahoslovlennia) of the couple by the bride's parents before the couple's departure for church; (11) the marriage ceremony (vinchannia) in church, usually on a Sunday; (12) the return (povernennia) to the bride's house; (13) the fetching (poïzd)—the arrival of the bridegroom's relatives at the bride's house to claim her, and their cold reception; (14) the introduction (predstavliuvannia)—an attempt by the bride's relatives to substitute other girls for the bride; (15) the reconciliation (pomyrennia)—the presentation of gifts to the bride's parents and the establishment of peace between the two families; (16) the division (rozpodil)—the cutting and distributing of the wedding bread among the wedding guests; (17) the departure (vid'ïzd) of the bride with her belongings to her husband's house; (18) the interception (pereima)—the capture of the bride by a group of young people, and her ransoming; (19) the reception (zustrich)—the welcoming of the bride in her new home by her mother-in-law; (20) the chamber (komora)—the defloration of the bride in the bridal chamber; (21) the invitation (perezva)—the public announcement of the bride's virginity and invitation of her parents to the bridegroom's house; (22) the supplements (prydatky)—a visit of the bride's relatives to the bridegroom's house, marking the climax of the wedding; (23) the toasting (perepii)—the postwedding feast at the house of the bride's parents; and (24) the gypsying (tsyhanshchyna)—the collecting of means for further merrymaking by the wedding guests throughout the village. This wedding ‘scenario’ became well established in the 16th to 19th centuries and had many regional variations. Each act in the drama involved magic ceremonies, wedding songs, and rituals.

After the October Revolution of 1917 the Soviet regime treated the traditional wedding, with its church ceremony, as a bourgeois vestige and launched a campaign against it. The concept of ‘free love,’ which was widely promoted in its place, proved to contribute to the dissolution of family life; hence, in the early 1920s marriage registration was made compulsory, and to give the event some solemnity, people were urged to combine the registration with a ‘red wedding.’ This ceremony, it was hoped, would supplant the traditional wedding. In essence the ‘red wedding’ was another public meeting, featuring a presidium, speeches, and a march with red banners and slogans. The ceremony did not catch on and by the late 1920s had been forgotten. In the countryside young people continued to hold the traditional wedding, and members of the intelligentsia and most urban residents simply registered marriages without any ceremony.

Forced collectivization, the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3, and terror, followed by the Second World War, led to the disappearance of the traditional wedding in Soviet Ukraine. It was revived after the war and provoked a reaction from the regime. The authorities encouraged ‘red weddings,’ ‘Komsomol weddings,’ ‘collective-farm weddings,’ and other forms of wedding, incorporating in them certain old traditions that appeared ‘progressive.’ But these new weddings failed to catch on. To divert young people from church marriages, the Communist party and the government decided to build ‘marriage palaces,’ later renamed ‘happiness palaces.’ The first marriage palace was opened in Kyiv in July 1960, and by 1963 there were a hundred of them in Ukraine. Five thousand palaces and houses of culture, also, were adapted for marriage registration ceremonies. Folklore specialists at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, the universities, and other institutions were instructed to design a ‘contemporary Soviet wedding,’ composers, to write new wedding songs, and poets, to write special wedding verses. On 15 July 1972 the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR adopted a law on the official marriage ritual: the marriage registration ceremony would be conducted by the ‘ritual matchmaker’—a member of the Soviet of Workers' Deputies—assisted by the staff of the civil registry office. The law specified how the officials were to be dressed, how the hall was to be decorated, and what the speeches were to contain. Couples who agreed to a Komsomol wedding were rewarded handsomely: often the entire cost of the wedding was covered by the couple's collective farm, plant, or institution, and the couple was given access to a special store stocked with generally unavailable goods. Despite these incentives the imposed wedding ceremony was not accepted widely in Ukraine. The 1986–8 campaign for an ‘alcohol-free wedding’ was also a failure. Most young people, especially in the villages, preferred the traditional wedding with a church ceremony and a good number of those who went through a Komsomol wedding also married secretly in a church. All of these Soviet-era wedding customs have been abandoned in independent Ukraine and many traditional elements have been restored. However, many of the traditional wedding rituals are no longer practiced, and those that have been preserved (the blessing, the wedding bread) are considerably simplified.

In Ukrainian communities abroad the traditional wedding has retained some archaic elements; in the 1950s, for example, Ukrainians in Romania still practiced the ritual of abduction of the future bride. Guests at a Ruthenian wedding in the former Yugoslavia, where weddings of 500 guests are not uncommon, are still decorated with rushnyky. Ukrainians in Canada and the United States hold on to some elements of the traditional wedding as an expression of national identity.

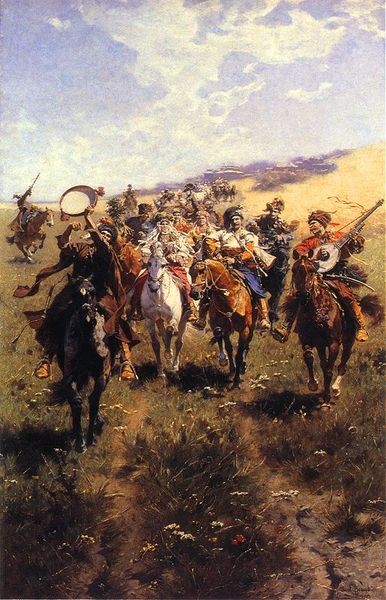

The earliest references to Ukrainian folk weddings can be found in medieval chronicles, church sermons, and religious works of the 11th to 15th centuries. There are descriptions of weddings from the 16th to 18th centuries, written mostly by foreign visitors to Ukraine (J. Łasicki, Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan, Hryhorii Kalynovsky). In the 19th and early 20th century, detailed descriptions of weddings in various regions of Ukraine were published. Fedir Vovk's historical study of the Ukrainian wedding, however, remains unsurpassed. Among recent books published in Ukraine on the traditional and contemporary wedding M. Shubravska's work is noteworthy. The traditional wedding is described frequently in Ukrainian literature—in Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko's Marusia and Svatannia na Honcharivtsi (Matchmaking at Honcharivka), for example; Taras Shevchenko's Nazar Stodolia and Naimychka (The Hired Girl); Yurii Fedkovych's Liuba-zhuba (Love Is Fatal), Sertse ne povchyty (You Can't Teach the Heart), and Beztalanne zakokhannia (Hapless Love); Ivan Franko's Velykyi shum (The Great Noise) and Ukradene shchastia (Stolen Happiness); Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's Tini zabutykh predkiv (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors); and in the works of Ukrainian Soviet writers, such as Mykhailo Stelmakh, Lina Kostenko, and Ivan Chendei. It has been depicted since the 18th century by Ukrainian painters, such as Kostiantyn Trutovsky, Mykola Pymonenko (Wedding [The Kyiv Gubernia], 1891), Ivan Izhakevych, Amvrosii Zhdakha, Anatolii Bazylevych, Valentyn Zadorozhny, Tetiana Yablonska, Heorhii Yakutovych, Feodosii Humeniuk, and Ivan Marchuk, and by non-Ukrainian painters, such as M. Shibanov, Vasilii Tropinin, Ivan Sokolov, and Józef Brandt.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kalinovskii, G. Opisanie svadebnykh ukrainskikh prostonarodnykh obriadov v Maloi Rossii i Slobodskoi ukrainskoi gubernii (Saint Petersburg 1776)

Volkov, T. [Vovk, Fedir.]. ‘Rites et usages nuptiaux en Ukraine,’ L'Anthropologie, 2–3 (1891, 1892); Ukrainian trans: ‘Shliubnyi rytual ta obriady na Ukraïni,’ in his Studiï z ukraïns’koï etnohrafiï ta antropolohiï (Prague 1928; repr, New York 1976)

Chubinskii, P. Trudy Etnografichesko-statisticheskoi ekspeditsii v Zapadno-russkii krai, vol 4 (Saint Petersburg 1877)

Grinchenko, B. Etnograficheskie materialy, sobrannye v Chernigovskoi i sosednikh s nei guberniiakh, 3 vols (Chernihiv 1895–9)

Iashchurzhinskii, Kh. ‘Svad’ba malorusskaia, kak religiozno-bytovaia drama,’ KS, 1896, no. 11

Hnatiuk, Volodymyr. ‘Ukraïns’ki vesil’ni obriady i zvychaï,’ Materiialy do ukraïns’koï etnolohiï, 19–20 (Lviv 1919)

Bielichko, Iu.; V’iunyk, A. Ukraïns’ke narodne vesillia v tvorakh ukraïns’koho, rosiis’koho ta pol’s’koho obrazotvorchoho mystetstva XVIII–XX stolit’ (Kyiv 1970)

Shubravs’ka, M. Vesillia, 2 vols (Kyiv 1970)

Zdoroveha, N. Narysy narodnoï vesil’noï obriadovosti na Ukraïni (Kyiv 1974)

Borysenko, V. Nova vesil’na obriadovist’ v suchasnomu seli (Kyiv 1979)

———.Vesil’ni zvychaï ta obriady na Ukraïni (Istoryko-etnohrafichne doslidzhennia) (Kyiv 1988)

Mykola Mushynka

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993).]

.jpg)