President of Ukraine

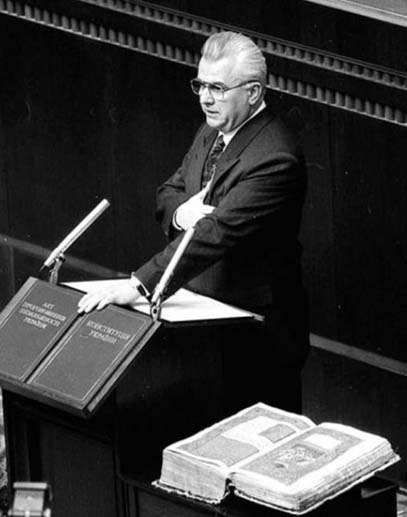

President of Ukraine (Президент України). Since the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, the highest political office in the land as head of state. Following precedents set by both the USSR (Mikhail Gorbachev, 1990) and RSFSR (Boris Yeltsin, 1991), the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR in May 1991 decided to create a presidency and in December along with the referendum on independence Leonid Kravchuk was elected as Ukraine’s first president. As with its exemplars there were difficulties of adjustment to accommodate the office of president into the preexisting Soviet Communist Party system of government. Throughout Ukraine’s era of independence the institution of president has not yet been consolidated into a stable role.

The relationship between legislative and executive branches of government in democratic polities can be conceived as being arranged on a spectrum with pure presidentialism at one end and pure parliamentarism on the other. Presidentialism entails a full separation of powers with executive and legislative branches independent of one another in terms of election and survival—neither can dismiss the other. Parliamentarism features a fusion of the two branches with the lives of both being interdependent—and, obviously, with no president. In between these two models is semi-presidentialism, where a prime minister and cabinet are situated between the president and the parliament. If the prime minister and cabinet are more dependent on the president than on the assembly, this sub-type is called presidential-parliamentary; if on the assembly, then parliamentary-presidential. Initially, Ukrainian lawmakers showed a preference for presidentialism, but eventually chose semi-presidentialism. Ukraine has in practice vacillated between the two sub-types.

Politicians in newly-independent Ukraine had no experience with Western systems of government. They were habituated to the authoritarianism of the Communist Party under one-man leadership with the window-dressing of a Supreme Soviet national assembly where there was no separation of powers. What has ensued after the introduction of a head of state is a prolonged period of constant readjustment in the relative powers of the president and the Supreme Council of Ukraine. This has manifested itself in an ongoing struggle for power among the occupants of the branches of government, an overstepping of constitutional limits, and often the personalization of the power of the president.

The statutory basis for the office of president in Ukraine begins with legislation adopted in 1991, where the office is described as ‘the highest official person in the Ukrainian state and head of the executive branch of government.’ Elected for a five-year term, the president’s powers were to be specified in the Constitution of Ukraine. The president’s status was refined by a law of 14 February 1992, where beyond being head of state the president was designated as ‘guarantor of civil rights and freedoms, of Ukraine’s state sovereignty, and upholder of the Constitution and laws of Ukraine.’ It placed the Council of Ministers of Ukraine under the president but also made it accountable to the Supreme Council of Ukraine. The latter could express a lack of confidence in the Cabinet, but the consequences of such action were unspecified. Pending adoption of the Constitution of Ukraine the early 1990s were characterized by continual but gradual efforts to change the structure of government away from Soviet practices to the principles of constitutionalism, taking into account the interests of the participants involved.

In preparing the new Constitution of Ukraine, many variants were presented and debated. Ultimately, the outline of a compromise characterization of the presidency emerged. Adopted in 1996, the Constitution of Ukraine stipulated (art 106) that the president: may dissolve the Supreme Council of Ukraine in case it fails to meet within a specific period of time; appoints and dismisses the prime minister; confirms and terminates the appointments of ministers and other officials on the prime minister’s recommendation; signs laws passed by the Supreme Council of Ukraine; and issues decrees within his competence. The president may be impeached (art 111) by the Supreme Council of Ukraine. The cabinet of ministers (art 113) remains responsible to the president and accountable to the Supreme Council. A vote of non-confidence in the Cabinet by the Supreme Council of Ukraine results in the Cabinet’s resignation (art 115).

Through coercion—by his Law on Power and the threat of a referendum—rather than through persuasion President Leonid Kuchma thus achieved the replacement of Ukraine’s 1978 Soviet Constitution of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as well as a presidential-parliamentary arrangement of institutions at the apex of power in Ukraine. In his second term beginning with his unconstitutional constitutional referendum in 2000 he embarked on the task of converting the executive-legislative arena into a parliamentary-presidential one in anticipation of either Viktor Yanukovych or Viktor Yushchenko’s winning the presidency. At the end of the Orange Revolution in December 2004, the Constitution of Ukraine was duly changed by agreement among all concerned such that the president would: propose a candidate for prime minister for the assembly’s approval having consulted with it beforehand; appoint ministers of defense and foreign affairs as well as heads of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine (RNBOU), and National Bank of Ukraine; and not appoint or dismiss other cabinet ministers. The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine would instead be fully answerable to the Supreme Council of Ukraine, which alone could dismiss the Cabinet after a vote of non-confidence. It could also dismiss individual ministers without consequences for the Cabinet as a whole.

These constitutional changes went into effect on 1 January 2006, seriously reducing President Viktor Yushchenko’s political authority during the second half of his troubled term in office. Among his troubles were that he had a falling-out with his Orange Revolution ally, Yuliia Tymoshenko, and was forced to bring Viktor Yanukovych, his competitor for the presidency, back as prime minister. He took the unconstitutional step of calling early parliamentary elections in 2007 which produced results identical to those of 2006. On the eve of the 2010 presidential election his popularity was in the single digits.

On winning the presidential election in 2010 against his main rival Yuliia Tymoshenko, Viktor Yanukovych proceeded to jail her and prevailed on the Constitutional Court of Ukraine to annul the 2004 amendments, returning Ukraine to the presidential-parliamentary model. This restored to the president the level of powers that had been in the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine and had allowed Leonid Kuchma to wield the ‘administrative resources’ of his office effectively, particularly in the 1999 elections. It meant Yanukovych could install his loyalists in law enforcement and security posts to harass political opponents, repress public demonstrations, and reward supporters.

Having triggered the Euromaidan Revolution in November 2013 and then fleeing the country in February 2014, Viktor Yanukovych was replaced by speaker of the Supreme Council of Ukraine Oleksandr Turchynov as acting president. This was in accordance with constitutional provisions in the case of a president being incapacitated. At the same time the Supreme Council of Ukraine restored the 2004 amendments, although the constitutionality of this action in respect of the powers of the president was debatable.

In May 2014, Petro Poroshenko was elected president on the first ballot among 23 contenders. His term of office was marked by a reluctance to reduce political corruption while pretending to do so, although he showed no tendency to abuse his own powers as president in the manner of Leonid Kuchma or Viktor Yanukovych. Poroshenko did, however, press for the appointment of Yurii Lutsenko as prosecutor-general despite the latter’s lack of legal training. Poroshenko lost his bid for re-election in 2019 to the novice politician Volodymyr Zelensky. Despite being a lawyer by training, Zelensky was not above breaking constitutional rules by calling for early elections to the Supreme Council of Ukraine as well as by making or interfering with appointments beyond his official remit. Like Poroshenko, Zelensky intervened boldly and regularly in the spheres of law enforcement and the judiciary for political purposes without ever being called to account. Ukraine’s first two post-Euromaidan Revolution presidents thus demonstrated the country’s political system’s lack of habituation to the requirements of rule of law and separation of powers as they are meant to operate at the highest level.

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation in February 2022, President Volodymyr Zelensky proved himself an outstanding wartime leader. He introduced martial law, relied predominantly on the RNBOU instead of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine or the Supreme Council of Ukraine for decision-making, and deferred presidential elections that were due in 2024. These were necessary decisions, but they also betrayed his impatience with operating within the institutional framework. Some of his other actions, such as the suspension of certain political parties’ activities of or the dismissal of the commander-in-chief, General Valerii Zaluzhny, whose growing popularity with the public suggested political ambitions, were seen as a continuation of Zelensky’s ongoing engagement in the informal back-room politics so characteristic of independent Ukraine in peacetime.

Presidents of Ukraine have made contributions, both good and ill, to the formation of the state and nation. Only one (as of 2024) has been re-elected to a second term, indicative of consistent public dissatisfaction with incumbents’ performance as well as of the health of electoral democracy in a relatively young post-Soviet country. Every president has also struggled to discard informal political maneuvering in favor of open democratic politics with the rule of law and limitations on their powers of office.

President Leonid Kravchuk is renowned for signing the Belavezha Agreement together with Boris Yeltsin of the RSFSR and Stanislau Shushkevich of the Belorussian SSR. The historic agreement terminated the USSR as a legal entity, created the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as its weak replacement, and affirmed Ukraine’s independent statehood. Kravchuk consistently defended that statehood and independence. But concentrating on his own conception of state-building, he neglected nation-building, launching a market economy, reforming the judicial system, and dealing with emerging business and regional elites. He set an important precedent by accepting defeat gracefully.

President Leonid Kuchma distinguished himself by navigating successfully among conflicting domestic interests as well as between the Russian Federation and the West in the foreign policy realm. He introduced independent Ukraine’s first Constitution, but undermined the rule of law by interfering with legal procedures when attempting to balance business interests, and setting in place a system of political corruption. While he embraced the idea of Ukrainian sovereignty, Kuchma was indifferent to, or at least inconsistent in, nation-building policy. He pursued a multi-vector foreign policy, which entailed maintaining good relations with Moscow and the West, but at the same time encouraged cooperation with NATO and the Euro-Atlantic community, which would not be favored by the Russian Federation. Embroiled by scandal over the Heorhii Gongadze affair, Kuchma left his successor in a weaker constitutional position than he had fought for and achieved for himself in the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine. His preferred successor, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted by the Orange Revolution, a revolt against his authoritarian manner of rule.

President Viktor Yushchenko, weakened by the poisoning attempt on him during the presidential campaign of 2004, saw his popularity drop to single digits by the end of his term. He appeared short-tempered, indecisive, unable to lead, and embroiled in needless personal battles with those around him. He nevertheless oversaw Ukraine’s entry into the World Trade Organization and pursued NATO membership. His economic achievements were undone by the global financial crisis of 2008. Yushchenko paid particular attention to the development of Ukrainian identity, arts, and culture. He memorialized the Holodomor, opened the KGB archives, and had the Baturyn Cossack settlement rebuilt. His failure to attack political corruption and the country’s economic problems contributed to his defeat in 2010.

Succeeding Viktor Yushchenko, President Viktor Yanukovych devoted himself to accumulating power and wealth. In the process he alienated not only the Ukrainian electorate, but also the Ukrainian and Russian oligarchic business elites, the West, and even his patron, Russian President Vladimir Putin. He dealt with political opponents (like Yuliia Tymoshenko and Yurii Lutsenko) by imprisoning them. His rule having been a blend of political power, greed, and criminality was symbolized by the legendary amount of money taken with him when he fled to the Russian Federation as well as by the ostentatious palace he left behind.

President Petro Poroshenko, faced with the annexation of the Crimea by the Russian Federation and military incursion into the Donets Basin, is credited with strengthening the Armed Forces of Ukraine and Ukraine’s defense industrial complex. He also reoriented Ukraine’s export trade away from the Russian Federation to the European Union and implemented an unprecedented number of reforms. He signed with the European Union the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement, Viktor Yanukovych’s deferral of which had sparked the Euromaidan Revolution. At the same time, despite having introduced the new anti-corruption agencies, he undermined their work. He did everything in his power to keep the business-and-politics nexus alive as well as controlling the legal system so as to dispense one law for friends and another for political opponents. He secured the tomos authorizing creation of a single Orthodox Church of Ukraine, but this did not save him from defeat in the 2019 election.

President Volodymyr Zelensky’s peacetime record was ambiguous. It was almost directionless. He led the nation to see itself as a unified civic political identity and brought a single-party majority into the Supreme Council of Ukraine. He fired his reformist prime minister after six months in office, replacing the entire Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine with seasoned technocrats. He threatened to put Petro Poroshenko, his predecessor, on trial and send him to prison, until dissuaded by foreign leaders. He believed he could negotiate settlement of the Donbas conflict with Vladimir Putin. He disbelieved the United States’s warnings of a Russian invasion and failed to prepare his people for war. Like Poroshenko, Zelensky attempted by all means to secure control of the legal apparatus of the state for political ends.

The Russo-Ukrainian war transformed Zelensky into an inspiring leader, reassuring the population, praising the Armed Forces of Ukraine, cultivating alliances, and garnering moral support from allies abroad. He sensibly replaced his favorites in his entourage with more competent professionals. His leadership transcended ethnic boundaries and his popularity soared. At the same time, the war offered Zelensky an excuse to short-circuit democratic procedures such as relying on the RNBOU instead of the Supreme Council of Ukraine to make decisions. The war did not dissuade him from pursuing petty political vendettas such as dismissing the chief of the defense staff, Valerii Zaluzhny, who appeared to be gaining too much appeal with the electorate and sending him to London as Ukraine’s ambassador. Presidential elections scheduled for 2024 did not take place and were deferred until after the war.

In Ukrainian politics a balance between institutions has never been achieved, nor do political actors have incentives to play by the rules, but by informal means (bribery and political corruption, patron-clientelism, informal understandings), hence the chronic stalemates which lead to further conflict and instability. Throughout the country’s independent history, public opinion has consistently been less favorable towards all political institutions, indicating a problem of legitimacy. Over time, the level of trust in every president erodes, even in emergencies. Volodymyr Zelensky, who began with 80 percent of the public’s trust in September 2019 was down to 37 per cent by February 2022, the eve of the invasion; in May 2022, he was at 90 per cent, which nevertheless shrank to 82 per cent by December 2024.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shugart, M.; Carey, J. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics (Cambridge 1992)

Todyka, Iu.; Yavorskii, V. Prezident Ukrainy: Konstitutsionno-pravovoi status (Kharkiv 1999)

D’Anieri, P. ‘Leonid Kuchma and the Personalization of the Ukrainian Presidency,’ Problems of Post-Communism 50, no. 5 (September–October 2003)

Matsuzato, K. ‘Semipresidentialism in Ukraine: Institutional Centrism in Rampant Clan Politics,’ Demokratizatsiya 13, no. 1 (Winter 2005)

Christensen, R.; Rakhimkulov, E.; Wise, C. ‘The Ukrainian Orange Revolution Brought More than a New President; What Kind of Democracy Will the Institutional Changes Bring?’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38 (2005)

Protsyk, O. ‘Constitutional Politics and Presidential Power in Kuchma’s Ukraine,’ Problems of Post-Communism 52, no. 5 (September–October 2005)

D’Anieri, P. ‘What Has Changed in Ukrainian Politics? Assessing the Implications of the Orange Revolution,’ Problems of Post-Communism 52, no. 5 (September–October 2005)

‘Povnyi tekst rishennia KS pro skasuvannia politreformy 2004 roku,’ Ukraïns'ka Pravda (1 October 2010)

D’Anieri, P. Understanding Ukrainian Politics: Power, Politics, and Institutional Design (Armonk, N.Y., and London 2007)

Shapoval, V. ‘Vykonavcha vlada v Ukraïni v konteksti formy derzhavnoho pravlinnia (dosvid do pryiniattia Konstytutsii Ukraïny 1996 r.),’ Pravo Ukraïny, no. 3 (2016) and no. 4 (2016)

Aslund, A. ‘Demise of Governance in Ukraine under President Zelensky,’ The Ukrainian Quarterly, no. 4 (2021)

Pisano, J. ‘How Zelensky Has Changed Ukraine,’ Journal of Democracy 33, no. 3 (July 2022)

D’Anieri, P. ‘Elections, Succession, and Legitimacy in Ukraine,’ Communist and Post-Communist Studies 57, no. 4 (2023)

Lebediuk, V. ‘Political Dynamics in Ukraine After Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion,’ Studia Europejskie—Studies in European Affairs, no. 4 (2023)

Karatnycky, A. Battleground Ukraine: From Independence to the War with Russia (New Haven and London 2024)

Bohdan Harasymiw

[This article was written in 2025.]