Music

Music [музика; muzyka]. Ukrainians are known popularly as a musical people with a remarkable legacy of folk songs and talented performers.

Medieval Ukraine. During the Middle Ages in Ukraine, three kinds of music developed. The first was music-making at the courts of the princes and boyars. Groups of musicians, local and foreign, resided at the princely courts and performed during festivals and banquets, praising the prince and entertaining the guests. Wandering musicians and actors, the skomorokhy, entertained their listeners with songs and acrobatic tricks. Many musical instruments were in use at that time in Ukraine, including stringed harps, metal and wooden trumpets and horns, wooden pipes, drums, and kettledrums.

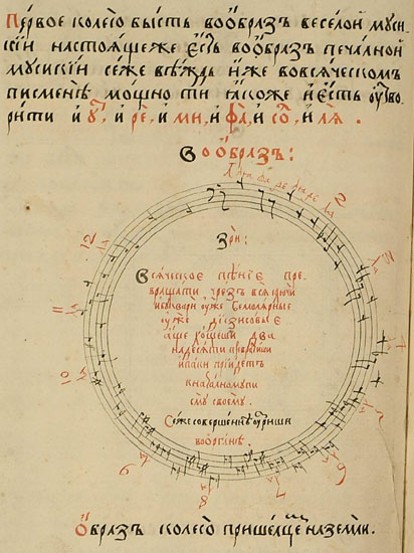

The first church music and its performers came from Byzantium and Bulgaria. These foreign musicians were the earliest conductors of local choirs and the first music teachers. Local influences began to be felt, however, with the increasing numbers of local musicians and performers of religious music. In the second half of the 11th century, the Kyivan Cave Monastery became the center for the development of religious music in Ukraine. The chief characteristics of religious music at that time were a cappella singing and monophony. The melodies were recorded in a nonlinear notation, called znamenna, written in above the words of the liturgical services. Another type of nonlinear notation was the kondakarna notation, which was used to note down liturgical singing, specifically the kontakia.

The third major type of music consisted of folk songs. These accompanied all significant events in a person's life and reflected the spiritual characteristics and the worldview of the Ukrainian people. Songs which were connected with ritual calendar changes figured prominently: the New Year carols (koliadky and shchedrivky), the rich cycle of spring rusalka songs, songs of the midsummer Kupalo festival, and so on. A large part of the repertoire was made up of songs associated with family and everyday life, as well as love songs and historical songs.

14th to 17th centuries. Church brotherhoods had an influential role in the development of music in Ukraine during this period. The brotherhoods in Lviv, Peremyshl, Ostroh, Lutsk, and Kyiv were particularly active in their religious educational work and founded brotherhood schools in which prime importance was given to the study of church music and music theory. A significant innovation was the introduction of polyphonic singing, leading to the development of the five-line notation called kyïvske znamia that replaced the non-linear notation. The ‘musical grammar,’ written by the musicologist and composer Mykola Dyletsky in 1675, was a complete description of the theory of polyphonic music. This work was rewritten and republished many times and in the 17th and 18th centuries became one of the basic texts of music theory throughout Eastern Europe. A favorite musical form of the time was the partesnyi concert, an a cappella composition for choir, consisting of one movement written to a religious text. Two music registers belonging to the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood in 1697 record 398 works by Ukrainian composers for 3 to 12 voices. Most of the works (120) are for 8 voices.

18th and 19th centuries. The 18th century witnessed a paradoxical situation in which Ukrainian music started to reach a higher level of maturity and sophistication that was ultimately absorbed by Russian musical development. The bases for developing a well-educated core of Ukrainian musical talent were expanding at this time. The Kyivan Mohyla Academy had an orchestra and choir comprising up to 100 musicians and 300 singers. The Hlukhiv Singing School, founded in 1738, provided thorough education for future musicians. Cossack starshyna families supported musical ensembles, if not whole orchestras, the most notable of which was found at the court of Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky (see Kyrylo Rozumovsky’s kapelle and orchestra, led by Andrii Rachynsky).

But the musical talents of Ukraine usually did not remain in Ukraine; they were being drawn into the developing Russian musical life on an ever-increasing scale. The start of this trend could be seen already in the late 17th century, when Mykola Dyletsky was summoned to Moscow by the tsar to teach the rudiments of polyphonic singing, and in the early 18th century with the appointment of Ivan Popovsky as the precentor of the imperial court choir (and his subsequent recruitment of singers from Ukraine). This tendency became particularly pronounced after the Rozumovsky family had established itself at the Saint Petersburg court in the 1740s and began seeking out talented musicians from Ukraine, such as Marko Poltoratsky, for service in the imperial capital. Likewise, the most talented graduates of the Hlukhiv Singing School were routinely brought to Saint Petersburg to further their music education.

The outcome of these practices can be seen by the late 18th century, when a trio of the most talented Ukrainian musicians of the age—Maksym Berezovsky, Dmytro Bortniansky, and Artem Vedel—composed exceptional works that became commonly regarded as ‘Russian’ music in the West. By the 19th century, Ukrainians, while still providing a source of recruits for musicians in Russia, had lost the dominant position (outside the Italian opera) they had earlier held in the Russian musical life of the Saint Petersburg court. In Ukraine itself, apart from a few notable exceptions (such as the compositions of Illia Lyzohub and Oleksander Lyzohub), musical life failed to develop much further than the level of traveling theater companies performing operettas or operas with broad thematic appeals (most notably Semen Hulak-Artemovsky's Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube and Mykola Arkas's Kateryna). Another area of indistinction between the two musical cultures was evident in folk music. The first compilations of Russian folk music, undertaken in the later 18th century by Vasyl Trutovsky and Ivan Prach, include Ukrainian folk songs. Over time these ‘Little Russian’ numbers were increasingly accepted as an integral part of the Russian musical heritage and employed by Russian composers (notably Modest Mussorgsky and Petr Tchaikovsky) in their works.

The provincial state of Ukrainian musical life began to change only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ironically one of the main instruments of this renewed development of Ukrainian musical life was the Russian Music Society, which established music schools (that later became conservatories) in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa (see Kyiv Music School, Kharkiv Conservatory, and Odesa Conservatory). The society restored a certain level of music training in Ukraine and cultivated a taste for refined music at least among certain segment of the population, providing the rudiments of an institutional and social base for later Ukrainian musical development.

Western Ukraine to the mid-19th century. Ukrainian musical life in Galicia saw some significant developments in the early 19th century. The main focus of Ukrainian musical life was in Peremyshl, where a distinctive ‘Peremyshl school’ of choral music was initiated by Mykhailo Verbytsky and Ivan A. Lavrivsky. The group had close connections with the Peremyshl Choir (est 1829) and the Peremyshl Music School, and influenced the work of subsequent composers, such as Viktor Matiuk, Sydir Vorobkevych, and Anatol Vakhnianyn. A second trend in Ukrainian musical life of this period was the development of an interest in Ukrainian folk music. In part this came about under the rubric of a general interest in the music of the peoples of the former Polish Commonwealth, which was studied by musicologists such as Wacław Zaleski and Karol Lipiński. Folk music was also studied by Ukrainians (eg, the members of the Ruthenian Triad). The general level of musical life in Western Ukraine was raised by the establishment of a singing school in Lviv, initially through the Saint Cecilia Society begun in 1826 through the efforts of Franz Xaver Mozart, and then with the founding of the Lviv Conservatory in 1830. The latter school, however, functioned largely as a Polish institution and did not actively foster Ukrainian musical development.

Late 19th and early 20th centuries. Considerable efforts were made in this period to develop a Ukrainian national school of music comparable to those established among the Poles, Czechs, Russians, and Norwegians. The key figure in this process was Mykola Lysenko, who collected and arranged a large number of Ukrainian folk songs and studied them in order to establish their cultural specificity. By 1904 Lysenko was able to found a school of music in Kyiv (see Lysenko Music and Drama School) that served as a major center for the fostering of Ukrainian music and musicians. He also toured through Ukraine with choruses under his baton in order to spread the sound of Ukrainian music.

Lysenko's work had a marked influence in Western Ukraine, where Ukrainians had not been subject to the same sort of state strictures as those under Russian rule. The study of Ukrainian folk music there had been able to develop at a considerable pace, Ukrainian music activists had been able to establish printing houses for the publication of music, and the Boian music society had built an effective network throughout Galicia. In this milieu composers such as Filaret Kolessa, Ostap Nyzhankivsky, Denys Sichynsky, Henryk Topolnytsky, and (later) Stanyslav Liudkevych and Vasyl Barvinsky were able to come to the fore and establish a degree of professionalism in all aspects of musical culture. As well, the Lysenko Higher Institute of Music was established in Lviv in 1903 to foster further Ukrainian musical development.

A high-water mark for the development of a Ukrainian national school of music was reached in 1917–22, when the Lysenko Music and Drama School in Kyiv was expanded into an institute (see Lysenko Music and Drama Institute), a state Ukrainian Republican Kapelle was formed, and a group of composers (including Mykola Leontovych, Kyrylo Stetsenko, and Yakiv Stepovy) was recruited to come to Kyiv to work for the new state institutions of Ukrainian musical life. These advances were short-lived, however. Leontovych, Stetsenko, and Stepovy all met early deaths (by 1922), the Republican Kapelle fled to the West, and the institutional base for Ukrainian musical development was unable to develop fully. The situation in Western Ukraine remained somewhat more promising, as musical life was allowed to develop without overt state interference, and the Lysenko Higher Institute of Music was able to establish a full network throughout Galicia before it was dismantled with the Soviet invasion of 1939.

Soviet Ukraine. The establishment of Soviet power in Ukraine has proved to be a mixed blessing for musical development. State support for the art has strengthened the music education system, underwritten the printing of music journals and scores, and provided steady employment for musicians, composers, and music critics. The state, however, has often fostered mediocre work in its demand for ideological conformity and in its effort to maintain socialist realism as a cultural policy. Consequently, a large repertoire of lackluster works dedicated to Vladimir Lenin, the glory of the Communist Party, the memory of the Second World War, heroic women workers, and like themes were commissioned over the years. In spite of these constrictions, composers such as Lev Revutsky, Borys Liatoshynsky, Pavlo Senytsia, Vasyl Barvinsky, Stanyslav Liudkevych, Viktor Kosenko, Valentyn Kostenko, Borys Yanovsky, Vsevolod Zaderatsky, Andrii Shtoharenko, Kostiantyn Dankevych, Yulii Meitus, Heorhii Maiboroda, Roman Simovych, Mykola Kolessa, and Anatol Kos-Anatolsky produced interesting and challenging works.

The most open period for musical composition in Soviet Ukraine was the 1920s, before the onset of Stalinism. A major body for the promotion of Ukrainian musical development at that time was the Leontovych Music Society, which was formed in 1922 and sponsored the flagship music journal Muzyka. The Leontovych society was dissolved in 1928 as a result of government pressure and restructured as a more pliable bodies, such as the All-Ukrainian Society of Revolutionary Musicians (Ukrainian acronym: VUTORM), which was renamed Proletmuz in 1931, and Association of Proletarian Musicians of Ukraine. In 1932 all music associations were dissolved and replaced by the Union of Composers of Ukraine. In the 1930s the Soviet regime established the concept of socialist realism as a norm for artistic activity, and the result was a wholesale retreat from the sort of composing done in the 1920s.

The ideological pressure eased somewhat only in the 1960s. The relaxation allowed for a whole group of young composers to use the newest means of musical expression. The members of this group, who went by the name ‘Kyiv Avant-Garde’, were Leonid Hrabovsky, Valentyn Sylvestrov, Vitalii Hodziatsky, Volodymyr Zahortsev, and Volodymyr Huba. The appearance of this group created much interest abroad, especially in the United States, although in Kyiv their achievements did not reach beyond a narrow circle of listeners. The composers Myroslav Skoryk, Lesia Dychko, and, among the younger generation, Yevhen Stankovych, Ivan Karabyts, and others have created original syntheses of the traditional with the modern.

A lighter musical form that developed in 20th-century Ukraine was stage music (estradna muzyka) or, in a more general sense, popular music. The art songs written by composers such as Platon Maiboroda constituted an early form of this genre. Popular stage music, however, came into its own in Ukraine only in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the development of a musical style based largely on North American rock and Europop models mixed with folk themes. The estradna style was emulated by many Ukrainian youth bands outside Ukraine.

Outside Ukraine. A small number of Ukrainian composers have worked outside Ukraine, although financial constraints have usually rendered it impossible to develop a full career from the writing of Ukrainian scores. The most notable of these figures have worked in France, Great Britain, Canada, and the United States of America; they include Fedir Yakymenko, Mykhailo Haivoronsky, Roman Prydatkevych, Oleksander Koshyts, and Pavlo Pecheniha-Uhlytsky before the Second World War and Antin Rudnytsky, Stefaniia Turkevych-Lukiianovych, Marian Kouzan, Volodymyr Hrudyn, Mykola Fomenko, George Fiala, and Ihor Sonevytsky after it. A number of Ukrainians within the general realm of the North American musical world, most notably Lubomyr Melnyk and Virko Baley, have also composed works with Ukrainian themes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hrinchenko, M. Istoriia ukraïns'koï muzyky (Kyiv 1922)

Barvins'kyi, V. ‘Ohliad istoriï ukraïns'koï muzyky,’ Istoriia ukraïns'koï kul'tury, ed I. Kryp’iakevych (Lviv 1937)

Kudryk, B. Ohliad istoriï ukraïns'koï tserkovnoï muzyky (Lviv 1937)

Wytwycky, W. ‘Music,’ Ukrainian Arts, ed O. Dmytriv (New York 1952)

Dovzhenko, V. Narysy z istoriï ukraïns'koï radians'koï muzyky, 2 vols (Kyiv 1957, 1967)

Rudnyts’kyi, A. Ukraïns'ka muzyka: Istorychno-krytychnyi ohliad (Munich 1963)

Arkhimovych, L.; Karysheva, T.; Sheffer, T.; Shreier-Tkachenko, O. Narysy z istoriï ukraïns'koï muzyky, 2 vols (Kyiv 1964)

Shreier-Tkachenko, O. (ed). Istoriia ukraïns'koï dozhovtnevoï muzyky (Kyiv 1969)

———. Istoriia ukraïns'koï muzyky (Kyiv 1980)

Hordiichuk, M.; et al (eds). Istoriia ukraïns'koï muzyky, 6 vols (Kyiv 1989–)

Wasyl Wytwycky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)