Memoir literature

Memoir literature (from French mémoire ‘memory’). A body of recollections written, in a literary, publicistic, or chronicle style, simultaneously with the occurrence of events (as in diaries and notebooks) or subsequently in recollection (as in autobiographies and travelogues). Among the oldest examples of the former group is the passage in Povist’ vremennykh lit (The Tale of Bygone Years) by Nestor the Chronicler which concerns the transferral of the sacred remains of the founder of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, Saint Theodosius of the Caves, entered into the chronicle in 1091. Early examples of the latter group are the autobiography of Prince Volodymyr Monomakh and a fragment of his Poucheniie ditiam (A Teaching for [My] Children), and a Chernihiv memoir by Hegumen Danylo, Zhytiie i khodzheniie Danyla, rus'koï zemli ihumena (The Life and Pilgrimage of Danylo, Hegumen of the Rus' Land, ca 1100), of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Ukrainian memoir literature can also be divided into two other categories: works written in Ukrainian or other languages by Ukrainians, and works written by foreigners about Ukraine.

Memoir literature is particularly rich from the 16th and early 17th centuries. Among the most notable works to have been preserved are the autobiography of the Kyivan hierodeacon Yoakym-Isaia, who sojourned in Muscovy in 1560–90; the notes of an unknown Galician of the late 16th or early 17th century concerning a pilgrimage to Jerusalem; the notes of Bozhko (Bohdan) Balyka of Kyiv about his adventures during the 1612 campaign on Moscow and other events; the notes of Metropolitan Petro Mohyla concerning events and meetings with various persons in the 1620s and 1630s; the memoirs of Hieromonk Ihnatii of Liubariv concerning the religious and cultural life of Galicia (Zhytiie i zhizn' prepodobnoho ottsa nasheho Iova [The Life and Times of Our Worthy Father Yov, 1621]); and the Diiariiush (Diary) of Hegumen Atanasii Fylypovych of Brest concerning the struggle with the Poles over the Orthodox faith, written in 1637–48.

The Bohdan Khmelnytsky era had a series of chroniclers, both Ukrainian and Polish. The most renowned among them was Samiilo Zorka, whose Diiariiush Samiilo Velychko purportedly draws on in his Skazanie o voini kozatskoi z poliakamy (Account of the Cossack War with the Poles), but which historians consider to be suspect. The memoirs of the Ukrainian nobleman Joachim Jerlicz about the events of 1620–73 mention the lost memoirs of the Jerlicz family and the Butovych family. Hegumen Teodosii Vaskovsky wrote about current events in Kyiv of the same period. Other accounts of the late 17th century include the notes of the Lviv merchant P. Kunashchak (or Kunashovych) about the life of a burgher in 1663–96; the Diiariiush and Keliini zapysky (Notes from a Monastic Cell) of Metropolitan Dymytrii Tuptalo (Rostovsky); the travelogues (journeys to Italy) of Hiermonk Tarasii Kaplonsky from the year 1697; and those of Hryhorii Skybynsky, who explored many Western European countries between 1686 and 1696.

Of the memoirs of the 18th century the more historically important are those of Cossack starshyna officers, such as the Dnevniki (Diaries) of Gen Mykola Khanenko, which covers the years 1719–21 and 1727–54; the Diiariiush: Dnevnyia zapiski (Diary: Daily Notes) of Yakiv A. Markovych, covering the years 1717–67; the Diiariiush of Hetman Pylyp Orlyk of the years 1720–32, which was written in Polish; and the Dnevnik (Diary) of Hetman Petro Apostol, written in French, covering the period May 1725 to May 1727. The regimental osaul of Pryluky, M. Movchan, provides valuable descriptions of daily life and includes the register of 1727. Movchan’s grandson, A. Mazaraki, continued the family chronicle for the period 1732 to 1787. Valuable information is found in the journal of the Pohar chamberlain S. Lashkevych, which covers the years 1768–82. More intimate is the autobiography of the colonel of Pryluky, Hnat Galagan. Also useful are the memoirs of church leaders, including the biographical notes of Bishop Yoasaf Horlenko (1740–4); the autobiography of Arsenii Matsiievych; the six-volume Diarium Quotidianum of Maksymiliian Ryllo, the bishop of Kholm and Peremyshl, which deals with religious events of 1759–1804; and the memoirs of the traveling priest Illia Turchynovsky. Of the travelogues of the 18th century those of Vasyl Hryhorovych-Barsky, of his travels through Europe, Asia, and Africa from 1723 to 1747, are among the most interesting. Daily and cultural life of the last quarter of the 18th century is described in Hryhorii Vynsky’s Moë vremia (My Time) and in the memoirs of M. Hornovsky, V. Hettun, Illia Tymkovsky, and others. Slobidska Ukraine is described by the architect V. Yaroslavsky, and Southern Ukraine appears in the memoirs of S. and O. Pyshchevych. The 19th-century memoirs of the former Zaporozhian M. Korzh (Ustnoe skazanie [Oral Account]) describe the last days of the Zaporozhian Sich. Right-Bank Ukraine at that time is described in Polish memoirs, particularly those concerning the Koliivshchyna rebellion. The memoirs of the Ukrainian Freemasons Mykhailo Antonovsky and Vasyl Lomykovsky are engaging and occasionally fantastic.

Among the many but as yet scantily published memoirs of the 19th century the Zhurnal (Journal) and autobiography of Taras Shevchenko are particularly important. Also notable are those of Mykola Markevych (an unpublished diary kept in the Markevych archive in the Saint Petersburg Pushkin Museum), Oleksii Martos (published in Russkii arkhiv, 1893, nos 7, 8), Apolon Skalkovsky (unpublished), Oleksander Kistiakovsky (unpublished), Hryhorii Galagan, and Vasyl Hnylosyrov. The autobiographies of Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Drahomanov, Volodymyr Antonovych, Mykhailo Hrushevsky (two), Dmytro Bahalii, and other leading figures are noteworthy and interesting. Other sources include the notes of O. Mykhailovsky-Danylevsky (military historian), the memoirs of S. Skalon (daughter of Vasyl Kapnist), the family chronicle of A. Kochubei, the notes of Andrii V. Storozhenko, M. Lazarevsky’s Pamiati moi (My Memories), and the memoirs of Yakiv Holovatsky, Lev Zhemchuzhnikov, I. Sbytnev, Mykhailo Chaly, Volodymyr Debohorii-Mokriievych, Borys Poznansky, Kostiantyn Mykhalchuk, Oleksander Lazarevsky, Oleksander Barvinsky (Spohady z moho zhyttia [Memories of My Life, 2 vols, 1912–13], about community and literary life in Galicia, 1860–88), Yevhen Chykalenko (Spohady, 1861–1907 [Memoirs, 1861–1907, 1955]), Sofiia Rusova, Oleksander Lototsky (Storinky mynuloho [Pages from the Past, 4 vols, 1932–4]), Maksym Slavinsky, Volodymyr Shcherbyna, Mykola Vasylenko (serialized in Ukraïns’kyi istoryk), and Mykola V. Storozhenko (unpublished). An impressive number of memoirs were published in Kievskaia starina, in Ukraïna (1914–30), in the collection Za sto lit, and elsewhere. Volodymyr M. Leontovych’s Khronika rodyny Hrechok (Chronicle of the Hrechka Family, 1932) and Dytiachi i iunats'ki roky Volodi Hankevycha (The Childhood and Youthful Years of Volodia Hankevych) are memoiristic. The memoir literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on Right-Bank Ukraine.

The early 20th century and the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917–20 are reflected in the memoirs of Dmytro Doroshenko (Moï spomyny pro davnie-mynule, 1901–1914 roky [My Memories of the Distant Past, 1901–14, 1949] and Moï spomyny pro nedavnie mynule, 1914–20 [My Memories of the Recent Past, 1914–20, 1923–4, 1969]), Yurii Kollard, Mykola Halahan, Oleksander Shulhyn, Volodymyr Doroshenko, Vadym Shcherbakivsky, Mykola V. Kovalevsky, Andrii Zhuk, Ivan Makukh, Olena Stepaniv, Antin Chernetsky, Mykhailo Tyshkevych, Vasyl Ivanys, Oleksander Skoropys-Yoltukhovsky, Fedir Dudko, Petro Bilon, Pavlo Zaitsev (fragments), and others. For a knowledge of the community and cultural life of that time Yevhen Chykalenko’s Shchodennyk (Diary, covering 1901–17) and the diary of Vadym Modzalevsky (particularly of 1915–17, unpublished) are particularly important. The fate of the notes of Heorhii Narbut’s circle in Kyiv (1918–20) and Serhii Yefremov’s diary is unknown.

The memoirs of the days of the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917–20 form a separate group. Notable political accounts include Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s Vidrodzhennia natsiï (Rebirth of a Nation, 3 vols, 1920) and Shchodennyk (Diary, of which five volumes, covering the years 1911 to 1936, have been published to date), Isaak Mazepa’s Ukraïna v ohni i v buri revoliutsiï (Ukraine in the Flames and Storm of Revolution), Osyp Nazaruk’s Rik na Velykii Ukraïni (A Year in Central Ukraine, 1920), Lonhyn Tsehelsky’s Vid legendy do pravdy (From Legend to Truth, 1960), Viktor Andriievsky’s Z mynuloho (From the Past, 2 vols, 1921, 1923), Mykola M. Kovalevsky’s Pry dzherelakh borot'by (At the Source of Struggle, 1961), Dmytro Dontsov’s Rik 1918, Kyïv (Year 1918, Kyiv), and the memoirs of Pavlo Skoropadsky (fragments published in Khliborobs’ka Ukraïna), Yevhen Konovalets, Oleksander Dotsenko, Mykyta Shapoval, and Arnold Margolin. Military accounts of the period have been published in Litopys Chervonoï kalyny, Kalendar Chervonoï kalyny, Za derzhavnist’, and other anthologies and periodicals. The more notable ones are those of Vsevolod Petriv, Viktor Zelinsky, Stepan Shukhevych, Antin Krezub (Osyp Dumin), Yurii Tiutiunnyk (H. Yurtyk), Volodymyr Kedrovsky, Oleksii Kobets (O. Varavva), Osyp Levytsky, and Nestor Makhno. Of the Soviet memoirs of the early 1920s those of Volodymyr Zatonsky and Oleksander Shlikhter are worthy of mention.

The events of the interwar period have not been well represented in memoir literature. Conditions in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, particularly in the 1930s, were not conducive to the keeping of such records, and those that have been published have largely been the recollections of émigrés. Soviet realities, such as the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3 and the Stalinist terror, were depicted by Semen Pidhainy in Nedostriliani (Those [Left] Unshot, 2 vols, 1949) and Ukraïns'ka inteligentsiia na Solovkakh (The Ukrainian Intelligentsia on the Solovets Islands, 1947), V. Yurchenko, Kost Turkalo in Tortury (Tortures, 1963), Ivan Nimchuk in 595 dniv soviets'kym v’iaznem (595 Days as a Soviet Prisoner, 1959), I. Shkvarko in Proklynaiu (I Curse), Vasyl Dubrovsky (fragments), and others. Ukrainian life in Galicia and in the emigration were the subject of the writings of Ivan Herasymovych, Ivan Kedryn, Ivan Makukh, Mykhailo Ostroverkha, Yevhen Onatsky, and Stepan Shakh. Since the Second World War the Shevchenko Scientific Society has produced a series of Western Ukrainian regional histories that contain much memoiristic material. The experiences of Ukrainians in the Bereza Kartuzka concentration camp were outlined in the memoirs of Volodymyr Makar and Isydor Nahaievsky, among others. Zynovii Knysh described the activities of the Ukrainian Military Organization and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in Western Ukraine.

Kost K. Pankivsky provides an account of the political situation in Ukraine during the Second World War in Vid derzhavy do komitetu (From a State to a Committee, 1957), as do the memoirs of Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Volodymyr Martynets, Vasyl Dubrovsky, Zynovii Knysh, and many others. The life of Ukrainians in the Soviet Army is described by D. Chub and M. Serhiienko. The struggle of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) is depicted in the accounts of Zynovii Matla, Lev Shankovsky, S. Khrin (Stepan Stebelsky), and many others, most of which were published in periodicals, such as Do zbroï. The history of the Division Galizien of the Ukrainian National Army is the subject of the memoirs of Pavlo Shandruk, Ye. Zahachevsky, and Yu. Krokhmaliuk (Yurii Tys), most of which were published in Visti kombatanta. The role of North American Ukrainians in helping the displaced persons is presented in the memoirs of Bohdan Gordon Panchuk and Stanley Frolick. The experiences of concentration camp survivors have been described by Mykhailo Bazhansky (Mozaïka kvadriv v’iaznychnykh [A Mosaic of Prison Quarters, 1946], O. Dansky (Khochu zhyty [I Want to Live]), Petro Mirchuk (V nimets'kykh mlynakh smerty [In the German Mills of Death, 1957; published in English translation, 1976]), and others. Memoirs of life in Soviet prisons and labor camps include Antin Kniazhynsky’s Na dni SSSR (At the Bottom of the USSR, 1959), U. Liubovych’s (Uliana Starosolska) Rozkazhu Vam pro Kazakhstan (Let Me Tell You about Kazakhstan, 1969), and Danylo Shumuk’s reminiscences. Numerous memoirs of Soviet partisan warfare have been published, such as those of Petr Vershigora and Sydir Kovpak.

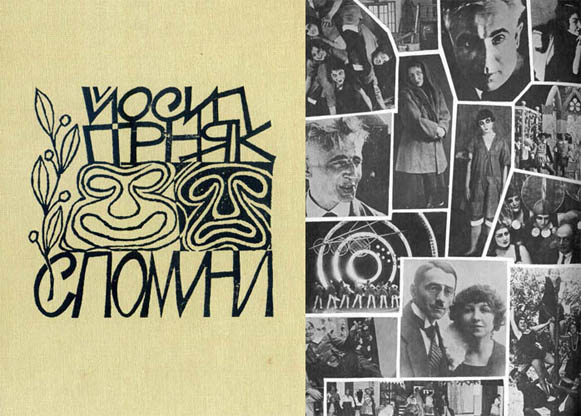

Accounts depicting the 1920s and 1930s include Ivan Maistrenko’s memoirs (1985), Oleksander Semenenko’s Kharkiv, Kharkiv (1976), Yosyp Hirniak’s Spohady (Memoirs, 1982), Ivan Koshelivets’s Rozmovy v dorozi do sebe (Conversations on the Way to Myself, 1985), Hryhorii Kostiuk’s Zustrichi i proshchannia (Meetings and Partings, 1987), Dokiia Humenna’s Dar Evtodeï (Eudora’s Gift, 2 vols, 1990), Valeriian Revutsky’s Po obriiu zhyttia (Along the Horizon of Life, 1998), and George Yurii Shevelov’s Ia-mene-meni i navkolo (I-Me-Mine and Around Me, 2 vols, 2001). Descriptions of the interwar years include Ulas Samchuk’s Na bilomu koni (On a White Horse, 1972) and Danylo Shumuk’s Perezhyte i peredumane (My Life and Thoughts in Retrospect, 1983; English trans: Life Sentence, 1984). The postwar years are described in Leonid Pliushch’s V karnavali istoriï (At the Carnival of History, 1977; published in English translation as History’s Carnival).

For Ukrainian cultural history the memoirs of and about writers and artists serve as important documents. Some have been collected in anthologies, such as Spohady pro Shevchenka (Memories of Taras Shevchenko, 1958), Ivan Franko v spohadakh suchasnykiv (Ivan Franko in the Memoirs of His Contemporaries, 1956), and Spohady pro Lesiu Ukraïnku (Memories of Lesia Ukrainka, 1963). Ivan Franko is discussed in individual accounts by Stepan Baran, Taras Franko, and others. The more important literary memoirs include Uliana Kravchenko’s Spohady uchytel’ky (Memoirs of a Teacher, 1935); Petro Karmansky’s Ukraïns'ka bohema (Ukrainian Bohemians, 1935); Bohdan Lepky’s Kazka moho zhyttia (The Tale of My Life, 1936–41); Yurii Klen’s Spohady pro neokliasykiv (Memoirs about the Neoclassicists, 1947); Mykhailo Drai-Khmara’s Bezsmertni (The Immortals, 1963); the memoirs of Ostap Vyshnia (fragments published); the diaries, notebooks, and autobiographical fiction (Zacharovana Desna [The Enchanted Desna) of Oleksander Dovzhenko; Arkadii Liubchenko’s diary; Ulas Samchuk’s Plianeta Di-Pi (D-P Planet, 1979) and Na koni voronomu (On a Black Horse, 1975); the memoirs of Halyna Zhurba about literary life in Kyiv during the civil war and the revolution; and Vasyl Sokil’s Zdaleka do blyz’koho (From Far Away to Close at Hand, 1987). Other works of autobiographical fiction include Maksym Rylsky’s poem Mandrivka v molodist' (A Journey into Youth, 1943) and Zhurba’s novellette Dalekyi svit (A Distant World, 1955). After a long interval caused by Soviet repressions the following memoirs were published in Soviet Ukraine: Mykhailo Rudnytsky’s Pys'mennyky zblyz'ka (Writers at Close Range, 3 vols, 1958–64), Yukhym Martych’s Iskry zhyvoho vohniu (Sparks of Living Fire, 1959), H. Hryhoriev’s U staromu Kyievi (In Old Kyiv, 1961), Yevhen Krotevych’s Kyïvs'ki zustrichi (Kyivan Encounters, 1965), and those of Rylsky, Vasyl Mynko, Prokhor Kovalenko, and L. Bilotserkivsky. Particularly valuable are Yurii Smolych’s accounts of the 1920s and 1930s, Rozpovid' pro nespokii (A Tale of Unrest, 1968), Rozpovid' pro nespokii tryvaie (The Tale of Unrest Continues, 1969), and Rozpovidi pro nespokii nemaie kintsia (The Tale of Unrest Has No End, 1970).

Toward the end of the 1980s, memoirs of the years of Stalinist terror began to be published in Kyiv. They include Volodymyr Sosiura’s Tretia rota (The Third Platoon, 1988) and I. Ivanov’s Kolyma 1937–1939 (1988).

Among artists’ and musical memoirs of the 19th and 20th centuries are Mariia Bashkirtseva’s Journal de Marie Bashkirtseff (1887), Oleksa Hryshchenko’s L’Ukraine de mes jours bleus (1957; translated into Ukrainian in 1959), Spohadamy (Recalled by Memories, 2 vols, 1947–8, about Heorhii Narbut), Oleksander Koshyts’s Spohady (2 vols, 1947–8) and Z pisneiu cherez svit (Across the World with a Song, 1952), and Ostap Lysenko’s Pro bat'ka Mykolu Lysenka (About My Father, Mykola Lysenko, 1957).

Ukrainian theater memoirs include those of Marko Kropyvnytsky, Mykola Sadovsky (Moï teatral'ni zhadky [My Theatrical Memories, 1930; 2nd edn 1956), Panas Saksahansky (Po shliakhu zhyttia [On the Path of Life, 1935]), Sofiia Tobilevych (Moï stezhky i zustrichi [My Paths and Encounters, 1957]), Ivan Marianenko (Mynule ukraïns'koho teatru [The Past of the Ukrainian Theater, 1953]), Mykhailo Donets (Teatral'ni spohady [Theatrical Memoirs]), and the many accounts about Les Kurbas written by Yosyp Hirniak, Valeriian Revutsky, and others.

Memoir literature on émigré life includes the works of Petro Karmansky (Mizh ridnymy v Pivdennii Amerytsi [Among Relatives in South America, 1923]), Oleksa Prystai (Z Truskavtsia u svit khmaroderiv [From Truskavets to the World of Skyscrapers, 4 vols, 1933–5]), Anatol Hak (Vid Hulai-polia do N’iu Iorku [From Huliaipole to New York, 1973]), P. Stasiuk, A. Romaniuk, O. Bryk, I. Humeniuk, and Sofiia Parfanovych. Memoirs about Ukrainian community life in North America have been written by numerous people, including Vasyl Chumer, Anthony Hlynka, Michael Luchkovich, Myron Surmach, and Petro Zvarych.

A large section of important memoir literature consists of foreign impressions of Ukraine. The more important ones, dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, were described by Volodymyr Antonovych in Memuary, otnosiashchiesia k istorii Iuzhnoi Rusi (Memoirs Pertaining to the History of Southern Rus') and in the surveys of F. Adelung, S.R. Mintslov, Veniiamyn Kordt, Dmytro Doroshenko, Elie Borschak, and Volodymyr Sichynsky.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Krevets'kyi, I. Ukraïns'ka memuarystyka (Kamianets-Podilskyi 1919)

Chaikovs'kyi, I. ‘Nasha memuarystyka,' Naukovi zapysky UTHI, 11 (1966)

Ivan Koshelivets, Bohdan Kravtsiv, Oleksander Ohloblyn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]