Marxism

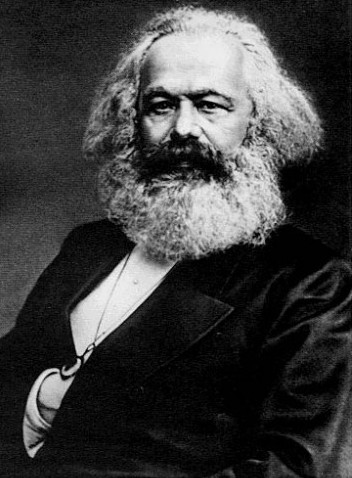

Marxism. The set of political, economic, philosophical, and social doctrines developed by Karl Marx (1818–83) and Friedrich Engels (1820–95). In Ukraine interest in Marxian ideas appeared as early as the 1870s. The economist Mykola Ziber was one of the first interpreters of Marx in the Russian Empire. Serhii Podolynsky corresponded with Marx and Engels and attempted to show that the laws of thermodynamics confirmed Marx's theory of surplus labor. In the late 1870s and early 1880s Ivan Franko wrote popularizations of Marxist theory and translated portions of Das Kapital and Engels's Anti-Dühring. In 1875 the first Marxist organization on Ukrainian territory, the South Russian Union of Workers, was formed in Odesa. Some tendencies in Ukrainian socialism at that time, however, were strongly critical of Marxism. Mykhailo Drahomanov and his disciple Mykhailo Pavlyk criticized Marxism on various grounds. As members of a stateless nation and as anarchists, they opposed the Marxian preference for centralism and the idea of state control of the economy; in particular, they objected to Marx and Engels's call for the restoration of a Polish state within historical boundaries that would include Ukrainian territory. They also felt that Marxism, which identified the urban proletariat as the only revolutionary class in capitalist society, had little to offer a nation whose masses were largely peasant; moreover, Marx and Engels's views of the peasantry as politically and economically backward and on the verge of extinction found few adherents among Ukrainians. Drahomanov, Pavlyk, and, later, Franko developed radicalism as an alternative to Marxian socialism.

Marx and Engels's views on Ukraine were shaped in relation to their views on Russia and particularly Poland. Both placed great hopes in a Polish revolution against Russia, which they considered the greatest menace to European democracy and the future of socialism. Because of their pro-Polish attitudes they often ignored the fact that the Polish revolutionaries were landowning gentry, and denied the existence of a separate Ukrainian nation. Engels in particular, during the Revolution of 1848–9 in the Habsburg monarchy, classified Ukrainians among the ‘nonhistoric’ peoples of East Central Europe who were counterrevolutionary by nature and doomed to extinction. By the 1870s, however, Marx and Engels began to hope for a revolution within Russia itself and consequently became more critical of Polish aspirations to Ukrainian territory.

By the beginning of the 20th century Marxism and Marxist political parties had become a serious force throughout the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary, including their Ukrainian-inhabited territories. In Galicia in the 1890s the dissident radicals Viacheslav Budzynovsky and Yuliian Bachynsky used a Marxist framework to argue that Ukraine was essentially a colony under imperialist rule and needed to become an independent state. Bachynsky and other dissidents left the Ukrainian Radical party in 1899 to form the avowedly Marxist Ukrainian Social Democratic party. The latter party's leading theoretician, Volodymyr Levynsky, devoted several works to the Marxist interpretation of the nationality question. In the Russian Empire the Revolutionary Ukrainian party also split in 1904–5 and gave birth to the Marxist Ukrainian Social Democratic Spilka and Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers' party. A leader of the latter party, Lev Yurkevych, wrote an important critique of Vladimir Lenin's position on the nationality policy with particular reference to the Ukrainian question. The economist Mykhailo Tuhan-Baranovsky was a leading exponent of legal Marxism in the 1890s and wrote a series of revisionist interpretations of Marxist economic theory. In general, prior to the Revolution of 1917, Ukrainian Marxists and Marxist parties inclined to the reformist rather than to the revolutionary wing of Marxism, although Yurkevych took a highly radical stand against participation in the First World War.

In Soviet Ukraine the Marxist Communist Party (Bolshevik ) of Ukraine established its monopoly in political life, and Marxism-Leninism became the official ideology. Marxist studies were concentrated at the Ukrainian Institute of Marxism-Leninism (UIML). Some intellectual independence and debate were tolerated until the end of the 1920s, and then a rigid vulgarized version of Marxism-Leninism was imposed by Joseph Stalin. Most Ukrainian Marxists who had been active in the 1920s were repressed. In 1931 the UIML was accused of harboring national deviationists and was broken up into an association of autonomous institutions, the All-Ukrainian Association of Marxist-Leninist Scientific Research Institutes (VUAMLIN), which was dissolved in 1937–8 and replaced in 1939 by the Ukrainian branch of the Institute of Marx-Engels-Lenin of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik).

In Western Ukraine Marxism enjoyed some prestige in the 1920s thanks to its association with Sovietophilism and the nationally conscious Communist Party of Western Ukraine (KPZU). In the 1930s the expulsion of the KPZU's leaders for nationalism, the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3, and the Stalinist terror in Soviet Ukraine ruled out any attraction Marxism might have had for most Western Ukrainians.

In Soviet Ukraine since the Second World War, Marxism has remained largely an instrument of Party policy. Members of the dissident movement, such as Ivan Dziuba and Leonid Pliushch, used Marxism as a tool of critical analysis. Mykola Rudenko wrote a critique of Marx' s economic theory from a physiocratic standpoint. Some Ukrainian scholars outside Ukraine have contributed to our understanding of Marxism. Roman Rozdolsky, a founder of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, achieved international recognition for his interpretation of Marx's economic thought. Vsevolod Holubnychy, Borys Levytsky, and Ivan Maistrenko [all associated with the left wing of the Ukrainian Revolutionary Democratic party and its newspaper Vpered (Munich), 1945–59] as well as John-Paul Himka and Bohdan Krawchenko have been influenced by Marxism or have studied it sympathetically.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hrushevs’kyi, M. Z pochyniv ukraïns’koho sotsiialistychnoho rukhu. Mykh. Drahomanov i zhenevs’kyi sotsiialistychnyi hurtok (Vienna 1922)

Iurynets’, V. Filosofs'ka geneza Marksa (Kharkiv 1933)

Doroshenko, D. Z istoriï ukraïns’koï politychnoï dumky za chasiv svitovoï viiny (Prague 1936)

Holubnychy, V. Soviet Regional Economics: Selected Works (Edmonton 1982)

Mace, J.E. Communism and the Dilemmas of National Liberation: National Communism in Soviet Ukraine, 1918–1933 (Cambridge, Mass 1983)

Rosdolsky, R. Engels and the ‘Nonhistoric’ Peoples: The National Question in the Revolution of 1848 (Glasgow 1986)

John-Paul Himka

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]