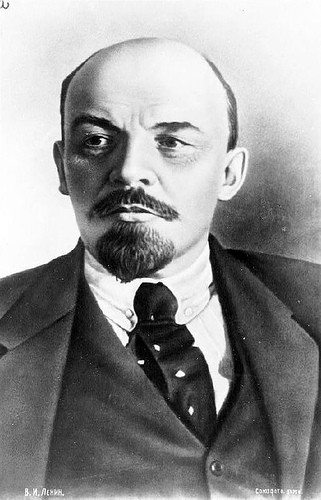

Lenin, Vladimir

Lenin, Vladimir (pseud of V. Ulianov), b 22 April 1870 in Simbirsk (now Ulianovsk), Russia, d 21 January 1924 in Gorkii, near Moscow. (Photo: Vladimir Lenin.) Russian revolutionary, founder of the Bolshevik party, leader of the Communist revolution (see October Revolutuion of 1917), and head of the Soviet state. After being expelled from Kazan University he studied Karl Marx and adopted his ideas. Lenin made important additions to Marxist doctrine in response to the demands of revolutionary practice. These additions form Leninism which reveals Lenin's skill as a tactician and his political flexibility. A key contribution was the concept of the revolutionary party, developed first in his What Is to Be Done? (1902) and One Step Forward, Two Steps Back (1904). Another was the concept of ‘democratic centralism.’ In The State and Revolution (1917) he justified his decision to seize power and to establish the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat.’ Lenin often reversed himself; he used the State Duma, for example, as a propaganda forum, recognized briefly the Ukrainian National Republic, established the Far Eastern Republic (1920–2) to further Bolshevik foreign policy, and introduced the New Economic Policy (1921) to restore the economy.

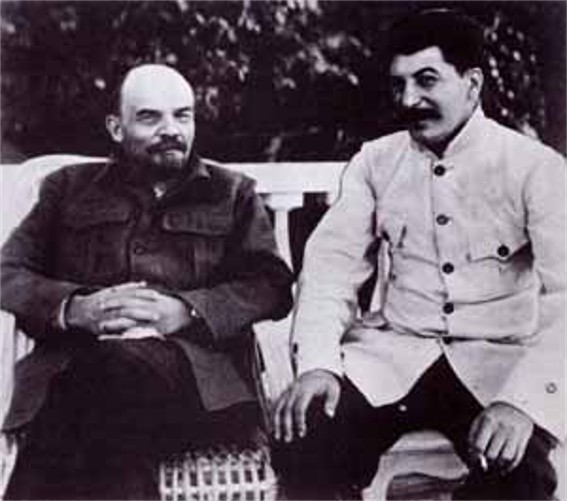

Lenin accepted violence and terror as legitimate tools of class war. He created the Soviet security police, the Cheka. He established the prototype of the totalitarian dictatorship, which tried to remake society and human nature and claimed the right to control all aspects of life. Lenin's ideological teachings and organizational methods paved the way for Joseph Stalin's brutal dictatorship.

His initial indifference and even hostility to the nationality issue expressed itself in his rejection of the ethnic criterion in party organization, his opposition to the Jewish Bund, and his commitment to centralism. The class struggle ruled out any national loyalties. He perceived ‘national culture’ as an instrument of the national bourgeoisie (landowners, priests, and the bourgeoisie). Lenin never visited Ukraine and only slowly acquired some understanding of its peculiar position. By 1912 he had associated Ukraine with Poland and Finland in his criticism of tsarist policies. Although he condemned nationalism, he paid lip service to the right of national self-determination, including independence, assuming all the time that it would not be exercised. He saw ethnic assimilation as ‘progressive,’ although he acknowledged the right of each people to use its own language and advocated language tolerance. Lenin believed that the right of national self-determination would be transformed dialectically into its opposite, and that ‘sometimes greater bonds obtain after free separation.’ He denounced Ukrainian socialists, such as Dmytro Dontsov and Lev Yurkevych (L. Rybalka), for advocating a separate Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers' party. He replied with abuse when Rybalka pointed out the inconsistency between Lenin's acceptance of national self-determination and his belief in the progressiveness of large states and in their continued existence. Rybalka had argued that the professed internationalism of the Bolsheviks was a veiled form of traditional Russian imperialism: Lenin's talk of the ‘fusion of nations’ and his desire to prevent the breakup of Russia were incompatible with his promise of national self-determination. Russia's collapse in 1917 compelled Lenin to confront the nationalities question on the practical level. He criticized the Provisional Government for refusing to grant Ukraine autonomy and used Ukrainian grievances to weaken the central government. But upon coming to power he adopted a hostile attitude to Ukrainian independence: he launched an invasion of Ukraine in January 1918. Although he was forced to recognize Ukraine's independence in the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, he sent the Red Army into Ukraine again in January 1919 and again in late 1919. To win Ukrainian support for the Bolshevik regime he set up a nominally autonomous Ukrainian Soviet government and promised to promote the Ukrainian language and culture. After consolidating his control over the peoples of the former Russian Empire, Lenin adopted, out of regard for their national feelings, a federated instead of a unitary form of state, in 1922. He pointed to Russian great-power chauvinism as the cause of nationalism in the smaller nations of the USSR. Some of his tactical opinions on the nationality problem provided the basis for the Soviet policy of Ukrainization that was introduced in 1923. After 72 years of near idolatry, Lenin is finally being seen for the imperialist and dictator that he really was. Since the end of 1990 open criticism of Lenin and what he stood for has spread through Ukraine and resulted in the dismantling of Lenin monuments in most cities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fischer, L. The Life of Lenin (New York 1964)

Possony, S. Lenin: The Compulsive Revolutionary (Chicago 1964)

Dziuba, I. Internationalism or Russification? (London 1968)

Rybalka, L. Rosiis’ki sotsial-demokraty i natsional’ne pytannia (Munich 1969)

V.I. Lenin pro Ukraïnu (Kyiv 1969)

Bakalo, I. Natsional’na politika Lenina (Munich 1974)

John Reshetar

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)