Kurbas, Les

Kurbas, Les (Oleksander) [Курбас, Лесь], b 25 February 1887 in Sambir, Galicia, d 3 November 1937 in Sandarmokh, Karelia region, RSFSR. Outstanding organizer and director of Ukrainian avant-garde theater, filmmaker, actor, and teacher; son of the Galician actor Stepan Yanovych (stage name: Kurbas) and actress Vanda Yanovycheva. In 1907–8 he studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and drama with the famous Viennese actor Josef Kainz. (Photo: Les Kurbas in 1908.) After graduating from Lviv University in 1910, he worked as an actor in the troupes of the Hutsul Theater (1911–12) and Lviv’s Ukrainska Besida Theater (1912–14), founded and directed the Ternopilski Teatralni Vechory theater in Ternopil (1915–16), and worked at Sadovsky's Theater in Kyiv (1916–17).

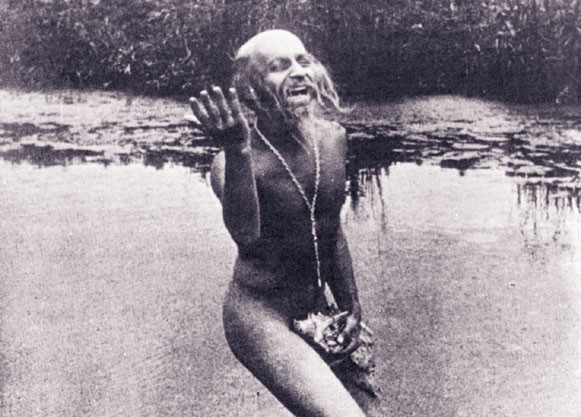

After the February Revolution of 1917 Kurbas reorganized an actors' studio he had founded in 1916 into the Molodyi Teatr theater (1917–19) in Kyiv and became the secretary of the journal Teatral’ni visty. (Photo: Les Kurbas in 1918). In Molodyi Teatr’s productions, which included the first performance in Ukrainian of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex (1918) (photo: scene from Oedipus Rex), Kurbas revolutionized Ukrainian theater, elevating it in style, esthetics, and repertoire from the provincial to the level of modern European theater. Influenced by Henri Bergson’s philosophy and the theatrical theories and experiments of Max Reinhardt, Georg Fuchs, and Edward Gordon Craig, Kurbas used Molodyi Teatr’s experimental productions to develop his own style of intellectual theater to replace the traditional Ukrainian ethnographic repertoire and traditional, realist psychological theater in general.

Kurbas’s idea of a new, philosophical theater (whose ultimate aim was to return to theater’s ritualistic roots and once again become a religious act) demanded a new type of actor. Rather than reliving the character’s emotions or identifying with him or her, Kurbas’s actor was supposed to objectify the character through the complete control of his or her body and voice and by means of several key techniques. The most important technique, transformation (peretvorennia), represented a theatrical symbol designed to reveal the spiritual and hidden elements by way of concrete images. Another crucial element of Kurbas’s approach was musical rhythm, which had to permeate and unify the entire production. To implement his principles, Kurbas placed much emphasis on his actors' intellectual and technical training, using in the latter the systems of gestures developed by François Delsarte and Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, as well as on architectural design, using the talents of Anatol Petrytsky and Mykhailo Boichuk.

In 1919 the Bolshevik authorities forced Molodyi Teatr to merge with the State Drama Theater, and Kurbas became the codirector, with Oleksander Zaharov, of the new Shevchenko First Theater of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. There, to great acclaim, he staged an interpretation of Taras Shevchenko's epic poem Haidamaky (The Haidamakas) (photo: scene from Haidamaky, 1920); this monumental production, with music by Reinhold Glière, became the standard by which all Ukrainian productions were measured in the 1920s. By 1920 the situation in Kyiv, devastated by continuous warfare, had become unbearable for actors, and Kurbas formed the Kyidramte touring theater troupe, which toured Bila Tserkva, Uman, and Kharkiv. Kyidramte’s repertoire included the first Ukrainian-language production of a play by William Shakespeare—Macbeth, which premiered in Bila Tserkva in August 1920. At this stage in his career, Kurbas gave up acting to concentrate solely on teaching and directing. Convinced that theater could be used as a powerful political instrument, in 1922 he renounced the estheticism of his earlier period and founded the Berezil artistic association in Kyiv as a left-leaning theater dedicated to the cause of the proletarian revolution.

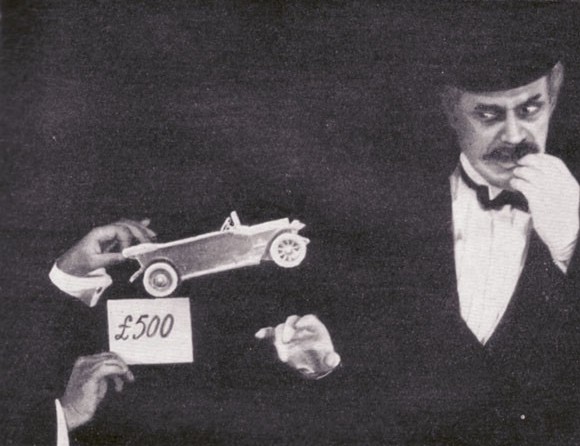

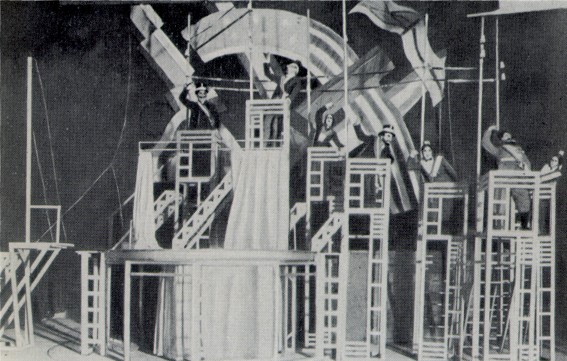

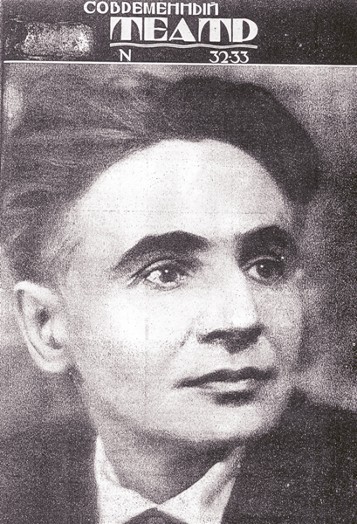

It was at Berezil in Kyiv (1922–6) and later Kharkiv (1926–33) that Kurbas's creative genius became most evident and transformed Berezil into the focal theater in Ukraine . (Photo: Les Kurbas in 1923.) At its height Berezil employed nearly four hundred actors and staff members and ran six actors' studios, a directors' lab, a design studio, a theater museum, and ten specialized committees. There Kurbas perfected his rigorous system for the intellectual and technical training of actors. It focused on ‘mime-dramas’, which shared many features of early avant-garde abstract dance and had to be fully mastered before actors were permitted to study the use of language. The main stylistic principle of Berezil's productions was the synthesis of speech, movement, gestures (which were supposed to be objectivized and remain separate from the actor's frame of mind and personal experiences), music, light, and decorative art into one rhythm or simple, dramatic language. Utilizing various elements of expressionism, constructivism, and other avant-garde styles, Kurbas’s innovative productions—eg, of Georg Kaiser’s Gas (1923) (photo: a scene from Gas), Upton Sinclair’s Jimmie Higgins (1923) (in which film was used for the first time on a Ukrainian stage) (photo: a scene from Jimmie Higgins), Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1924) (photo: a scene from Macbeth), and Fernand Crommelynck's Tripes d'or (1926) (photo: a scene from Tripes d'or)—challenged the traditional principles of realist psychological theater and often anticipated the later experiments of such directors as Bertolt Brecht and Antonin Artaud. Of particular importance for the development of Ukrainian drama and theater was Kurbas’s collaboration with the most important Ukrainian playwright of the 1920s, Mykola Kulish, three of whose plays became part of Berezil’s repertoire. (Photo: a scene from M. Kulish's People's Malakhii, 1927.)

In 1925 a lively public dispute about Kurbas and Berezil erupted. Soviet critics and Party officials denounced Berezil’s complex avant-garde style, inaccessibility to the masses, intellectual sophistication, and ‘antidemocratic stance.’ Nonetheless, Berezil was still recognized as Ukraine’s best theater, and in 1926 it moved to the then capital of Soviet Ukraine, Kharkiv. There Berezil became a focal point of a ‘theater dispute’ (part of the broader Soviet Ukrainian Literary Discussion), whose most important public forums in 1927 and 1929 represented confrontations between leading Soviet Ukrainian cultural figures (including Kurbas, Kulish, and Mykola Khvylovy) and theater traditionalists loyal to the Party (eg, Hnat Yura) as well as Soviet critics and officials (eg, Ivan Kulyk). Under mounting Party criticism, Berezil was forced to exclude from its repertoire most of Kulish’s plays and to stage second-rate dramas by Ivan Mykytenko, a Party favorite whose works adhered to the principles of socialist realism. Kurbas defiantly responded to this infringement on artistic freedom by completely rewriting Mykytenko’s Dyktatura (Dictatorship) and turning it into a musical that became one of his most notable directorial achievements. (Photo: a scene from Dictatorship, 1930.)

As the Party’s control over all spheres of cultural and political life in Ukraine tightened in the 1930s, Kurbas’s ideas and his dynamic, innovative, and often controversial productions were condemned as nationalist, rationalist, formalist, and counterrevolutionary. In October 1933 he was dismissed as the director of Berezil, and all of his productions were banned from the Soviet Ukrainian repertoire. To avoid further persecution, he moved to Moscow to join the GOSET (the State Jewish Theater) and work there on a production of King Lear starring Solomon Michoels. (Photo: Les Kurbas in 1933.) But soon after, in December 1933, he was arrested by the NKVD (photo: Les Kurbas, prison photo) and imprisoned on the Solovets Islands in the Soviet Arctic. There he became a victim of the mass executions of prisoners marking the twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917. Most of his archival materials, including all of his films, were destroyed.

Kurbas left his mark in the history of Ukrainian theater as an innovative organizer and teacher and daring experimental director. At Molodyi Teatr he introduced a modern European repertoire and style of acting. At Berezil he broke down the old forms of Ukrainian theater and, after a long period of searching and enthusiastic experimentation with German expressionist theater and the theories of constructivism, succeeded, in his productions of Kulish's plays, in creating a unique, Ukrainian expressionist theater. With his production of Kaiser's Gas in 1923, Kurbas broke completely with traditional Ukrainian realist, ethnographic theater to present spectacles that forced the audience to become active participants rather than passive observers. He combined his intellectualism and philosophical interpretation of plays with a brilliant synthesis of rhythm, movement, and avant-garde theatrical and visual devices, including the use of film, and managed to gather together the best actors, directors, set designers (eg, Vadym Meller), and playwrights in Ukraine. At the Berezil studios and Kyiv (1922–6) and Kharkiv (1926–33) music and drama institutes (see Lysenko Music and Drama Institute and Kharkiv Theater Institute), he trained an entire generation of Ukrainian actors and directors, including Danylo Antonovych, Borys Balaban, Yevhen Bondarenko, Amvrosii Buchma, Valentyna Chystiakova (Kurbas’s wife), Olimpiia Dobrovolska, Leontii Dubovyk, Sofiia Fedortseva, Liubov Hakkebush, Yosyp Hirniak, Domian Kozachkivsky, Marian Krushelnytsky, Lidiia Krynytska, Ivan Marianenko, Dmytro Miliutenko, Fedir Radchuk, Polina Samiilenko, Iryna Steshenko, Oleksander Serdiuk, Volodymyr Skliarenko, Borys Tiahno, Nadiia Tytarenko, Nataliia Uzhvii, and Vasyl Vasylko.

Kurbas’s theoretical and polemical articles appeared in journals such as Teatral’ni visty, Nove mystetstvo, Muzahet, Hlobus, Vaplite, Radians’kyi teatr, and Berezil's Barykady teatru (1923–4), which he edited. He was posthumously ‘rehabilitated’ after Stalin's death, but a serious study of his artistic legacy was not allowed to be published in Ukraine until the late 1980s. The first (very limited and heavily censored) edition of his writings appeared in Kyiv in 1988; the most complete edition to date, Filosofiia teatru (Philosophy of the Theater), appeared there in 2001. An extensive collection of documents and memoirs about him was published in Baltimore in 1989.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hirniak, Yosyp. ‘Birth and Death of the Modern Ukrainian Theater,’ in Soviet Theaters 1917–1941: A Collection of Articles, ed Martha Bradshaw (New York 1954)

Vasyl'ko, V. S. (ed). Les’ Kurbas: Spohady suchasnykiv (Kyiv 1969)

Smolych, Iurii. Pro teatr (Kyiv 1977)

Hirniak, Iosyp. Spomyny (New York 1982)

Boboshko, Iu. M. Rezhyser Les' Kurbas (Kyiv 1987)

Labinskii, M. G. ; Taniuk, L. S. (comps). Les' Kurbas: Stati i vospominaniia o L.Kurbase. Literaturnoe nasledie (Moscow 1987)

Revuts'kyi, Valeriian; Zinkevych, Osyp (eds). Les’ Kurbas: U teatral’nii diial’nosti, v otsinkakh suchasnykiv—dokumenty (Baltimore 1989)

Labins'kyi, M. H. (ed). Molodyi teatr: Heneza, zavdannia, shliakhy (Kyiv 1991)

Volyts'ka, I. V. Teatral'na iunist' Lesia Kurbasa (problema formuvannia tvorchoï osobystosti (Lviv 1995)

Korniienko, Nelli. Les’ Kurbas: Repetytsiia maibutn'oho (Kyiv 1998)

Makaryk, Irena R. Shakespeare in the Undiscovered Bourn: Les Kurbas, Ukrainian Modernism, and Early Soviet Cultural Politics (Toronto 2004)

Valentyn Haievsky, Marko Robert Stech

[This article was updated in 2006.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1923).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(1923).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)