Humoristic and satiric press

Humoristic and satiric press. The humoristic press in Ukraine emerged almost at the same time as the general press. The first Ukrainian newspapers contained—in addition to chronicles of events—scholarly, literary, and satirical material. Khar’kovskii Demokrit (1816) had a humor section, while Dnewnyk Ruskij (1848) and the women’s journal Lada (1853) of Lviv published humorous short stories. However, political censorship by the Russian and Austrian regimes and restrictions placed on the use of the Ukrainian language in the Russian Empire severely limited the early development of the humoristic press.

The first expressly humorous and satirical magazines appeared during the 1860s; these circulated only in manuscript form in very limited circles. Pomyinytsia (1863–4) was compiled by members of the Hromada of Kyiv to poke fun at the opponents of the Hromada. At the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary in Lviv, Anatol Vakhnianyn’s Klepalo circulated from 1860 to 1863; it was populist in orientation. More biting, and well illustrated by Yu. Dutkevych, was Omelian Partytsky’s Homin. Issues of these magazines were frequently confiscated by the seminary’s administration. Besides satirizing life in the seminary, they commented on community affairs and political events in contemporary Galicia. The first printed humor magazine was Dulia, one issue of which appeared in 1864, probably under the editorship of Antin Kobyliansky. It was followed by Yu. Moroz’s Kropylo in Kolomyia (1869) and the Russophile Strakhopud, first published in Vienna (1863–8) under the editorship of Osyp Livchak, but subsequently revived in Lviv by I. Arsenych and Volodymyr Stebelsky (1872–3), S. Labash (1880–2), and O. Monchalovsky (1886–93). Andrii Ripai, V. Kimak, and Kyrylo Sabov’s Sova was published in Uzhhorod and Budapest (1871), and I. Semaka’s semimonthly Lopata, in Chernivtsi (1876).

The political differentiation of 1880–1905 and the debates between Ukrainophiles and Russophiles in Galicia provided great impetus to the development of the humoristic press. In Lviv Zerkalo (1882–3) and Nove zerkalo (1883–5) were edited by Kornylo Ustyianovych. Journals called Zerkalo appeared again in Lviv in 1889–93 (published by Vasyl Lukych, Kost Pankivsky, and I. Krylovsky) and in 1898–1909 (published by O. Dembytsky). The weekly Antsykhryst (1902) was published by S. Terletsky and Osyp Shpytko in Chernivtsi, and I. Kuntsevych’s Komar (1900–6) appeared in Lviv.

The Revolution of 1905 brought some relaxation of controls in Russian-ruled Ukraine and, along with a revival in political and cultural life, a strong interest in humor magazines. Humorous feuilletons began to appear in general newspapers. In Kyiv, Volodymyr Lozynsky published Shershen’ (1906) and Pavlo Bohatsky published Khrin (1908), but these were suppressed by new restrictions and censorship. The comparatively more liberal political climate in this period in Galicia gave rise to Osa (1912), published by P. Odynak and with caricatures by Yaroslav Pstrak, and S. Terletsky’s Zhalo (1913–14).

The First World War brought new proscriptions on publishing in Ukrainian. At the same time, a new kind of press emerged under the auspices of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen on the fronts, in prisoner of war camps, and later in internment camps in Poland and Czechoslovakia. These journals came out irregularly and were printed on very primitive hectographs or circulated in manuscript form. The Ukrainian Sich Riflemen’s humor magazines included Samokhotnyk (1915–19), published by the Press Office of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen and edited by Myroslav Irchan, K. Kuzmovych, Antin Lototsky, and others, and well illustrated by Osyp Kurylas and Lev Gets; Samopal (1916); USUSU (1916–17), edited by Yu. Kalamar; Smittia; and Tyfusna odnodnivka. Magazines published in prisoner of war camps and internment camps included Kharakternyk (1920–1), edited by Hryts Hladky; Promin’ (1921); Okrip (1921); Polyn; Grymasa (1921); Komar (1920); Zhalo and Avans published in Wadowice; Oko and Sych in Kalisz; Lystok Ob’iav in Pykulychi; Blokha and Budiak in Strzałków; and Vzad (1919–21), illustrated by Edvard Kozak. Other magazines included Lezhukh, published in Tuchola (1921); Koliuchky in Częstochowa and Warsaw (1926–9); and Kamedula, which appeared in Liberec, Czechoslovakia (1919–20).

Under the Ukrainian National Republic and Hetman government independent humor magazines enjoyed a brief renaissance. Gedz (1917–18), the weekly Budiak, well edited by S. Panochini (1917), and Rep’iakhy (1918) all appeared in Kyiv. Numerous provincial newspapers also contained much humorous content. After 1920 these journals inspired similar magazines in cities with large communities of Ukrainian émigrés: in Vienna, Ieretyk and Smikh, edited by Oleksander Oles; in Prague, Vikhot', Gedz, Liushnia, Oko, Rep’iakh, Satyrykon, and Ukraïns'kyi kapitalist; and in Poděbrady, Absurd, Enei, Kropyva, Metelyk, Podiebradka, Podiebrads'ka hlidka, and others.

The partition of Ukraine among four states dictated the character of the humoristic press in the interwar period. In Soviet Ukraine during the early 1920s, humor was placed at the service of propaganda. During the New Economic Policy, when censorship was eased somewhat, some satirization of everyday and literary-artistic themes was permitted, including even sharp criticism of opposition to Ukrainization by Russified city dwellers and the Soviet bureaucracy. In the 1920s and early 1930s, popular humor magazines included Chervonyi perets’ (1922), Zhuk (1923–4), Havrylo (1925–6), the Russian-language V chasy dosuga, Novyi bich, Struzhki (1922), Krasnaia osa, Krasnoe zhalo (1924), and Uzh (1928–9) in Kharkiv; Bumerang (1927) and the Russian Tiski (1923) in Kyiv; the Russian Bomba, Burzhui, Shpil'ka (1918), Krasnyi smekh (1919), Oblava (1920), and Komsomol'skii Krokodilenok (1923) in Odesa; Ternytsia in Bila Tserkva; and Zhyttia i humor (1928) in Zhytomyr. In addition, most general literary magazines and newspapers contained satire of political and everyday life—the magazine Znannia (1923–35), Sil's'kohospodars’kyi proletar (1921–7), Selianka Ukraïny (1924–31), Vsesvit (1925–34), Uzh (1928–9), and especially Bezvirnyk (1925–35), in which satirists turned their attention to the war on religion. The satirical semimonthly Chervonyi perets’ resumed publication in Kyiv in 1927. In 1933, however, many of its collaborators were persecuted, and humor magazines in general fell victim to Stalinist repression. Perets’, which succeeded Chervonyi perets’, benefited from a temporary relaxation of censorship in 1944–5 (in the 1940s a special edition of the magazine was published for Western Ukraine), only to be severely criticized in the following year. It was even the subject of special criticism by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. After 1953, official directives decreed that a ‘critical’ course be strengthened in the entire USSR. As a result the humorous sections of newspapers and some journals (eg, the illustrated Ukraïna) were expanded. Most of this humor was intended to encourage labor discipline and to combat the adoption of Western styles and habits. Many caricatures and satirical feuilletons were published in factory newspapers, and placards and posters were displayed in special cases in city streets. The most noteworthy caricaturists of that time included Valentyn Lytvynenko, Oleksander Koziurenko, V. Hlyvenko, Oleksander Dovhal, Oleksander Dovzhenko, L. Kaplan, and A. Vasylenko. The style of their caricatures is so similar that it is often difficult to distinguish between these artists. By official decree, satire was directed against the forces of reaction, manifestations of bourgeois and nationalist ideology, and all things that hindered the construction of communism.

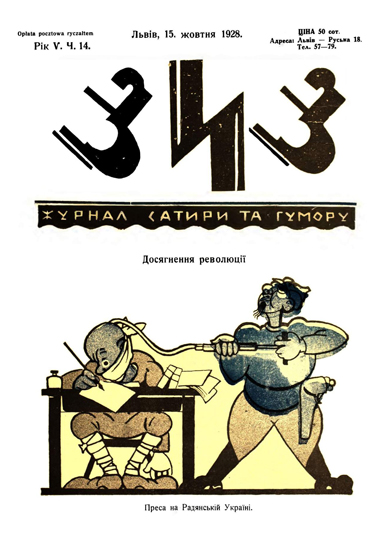

In interwar Galicia, humor magazines contended with prohibitions, confiscations, and financial difficulties; only by frequently changing publishers and names of publications were they able to maintain a continuity in publication before 1924. Early humor magazines of this period were Budiak, edited by Stepan Charnetsky (1921–2); Gudz, edited by D. Krenzhalovsky (1922); Zhalo, edited by P. Buniak; and Masky (1923), edited by Mykola Holubets. These were succeeded by Zyz (1924–33), edited by Lev Lepky. The co-operation of Edvard Kozak ensured the high level of quality of this publication. Roman Pashkivsky’s Zhorna (1933–4) was displaced by Kozak’s Komar (1933–39), which became the training ground for the humorists and caricaturists who worked with him in the emigration. Notable illustrators in the humoristic press of the period were Pavlo Kovzhun (Izhak), Osyp Sorokhtei, Petro P. Kholodny, Robert Lisovsky, and R. Chornii. After the Second World War caricaturists such as Lev Senyshyn, Viktor Tsymbal, Myron Levytsky, Borys Kriukov, Oleksander Klymko, Mykola Butovych, Mykhailo Dmytrenko, and Liuboslav Hutsaliuk also deserve mention. The satire in Galician humor magazines was directed mostly at Bolshevik policies in Soviet Ukraine, although they also satirized Ukrainian cultural and political life under Poland. Humorous material naturally was also published in the general press. The contributors included Tyberii Horobets (Stepan Charnetsky), Halaktion Chipka (Roman Kupchynsky), Lele (Lev Lepky), Fed Tryndyk (Vasyl Hirny), Iker (Ivan S. Kernytsky), Babai (Bohdan Nyzhankivsky), Teok (Teodor Kurpita), Andronik (Lev Senyshyn), I. Chornobryvy, Vasyl Levytsky-Sofroniv, and Ivan Sorokaty (Yurii Shkrumeliak).

In Transcarpathia and Bukovyna, the following humor magazines were published: Sova (1922–3), edited by L. Shutka, in Uzhhorod; Ku-Ku (1931–3) in Mukachevo; and Shchypavka, Zhalo (1926), Budiak (1930–1), and Chortopolokh (1936–7) in Chernivtsi.

The displaced persons camps of the post–Second World War period were fertile grounds for the development of the humoristic press. Dozens of journals and magazines appeared, although most were short-lived, irregular, and printed on primitive presses. The more important of these émigré publications were Teodor Kurpita’s Ïzhak, which changed to Ïzhak-Komar and then Komar (Munich, 1946–8), and Edvard Kozak’s Lys Mykyta, later published in the United States of America.

In North America, the humoristic press consisted mostly of short-lived and irregular magazines that were often more popular than the daily political press. In the United States, these included Osa (1902–3) in Olyphant, Pennsylvania; Molot (1908–12, 1919–23), Shershen’ (1908–11), Osa (1912–13), Iskra (1917–20), Lys Mykyta (1920–3), Perets’ (1923–5), Puhach (1925), Smikh i pravda (1926–8), Boievi zharty (1936), Kol’ka (1936–8), Oko (1939), Mykyta (1948–56), and E. Berezynsky’s Nove Tochylo, all in New York; Osa (1918–29, 1931), Batih (1921), Lys (1950), all in Chicago; and Edvard Kozak’s Lys Mykyta, published in Detroit from 1951. In Canada, Pavlo Krat published the anti-clerical Kropylo (1913) and Kadylo (1913–18), and in Winnipeg Yakiv Maidanyk published Vuiko (1918–27) and Stepan Doroshchuk published Tochylo (1930–47). Toma Tomashevsky’s Harapnyk (1921–35) appeared in Edmonton. Humorous almanacs such as Humorystychnyi Kaliendar Veselyi druh (1918–27) and Humorystychnyi Kaliendar Vuika (1925–32) also appeared.

In the 1930s in Buenos Aires Shershen’ and Batizhok were published, and Yu. Serediak’s Mitla appeared from 1949 to 1976. In Curitiba, Brazil, Batizhok was published as a supplement to the newspaper Khliborob (Curitiba) (1938–40). In Australia Perets’ (1950), Shmata (1970–1), and Osa (1972) were all published, and in London, England, Osa appeared from 1961 to 1974.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Babiuk, Andrii. ‘Strilets'ka presa,’ Visnyk SVU (1917)

Hnatiuk, Volodymyr. ‘Rukopysni humorystychni chasopysy,’ in ZNTSh, 130 (1920)

Chyzh, Iaroslav. ‘Pivstolittia ukraïns'koï presy v Amerytsi,’ in Kalendar Ukraïns'koho Robitnychoho Soiuzu (Scranton 1939)

Zhyvotko, Arkadii. Istoriia ukraïns'koï presy (Regensburg 1946)

Butnyk-Sivers'kyi, Borys. ‘Hazetna karykatura na Ukraïni v roky inozemnoï voiennoï interventsiï ta hromads’koï viiny,’ Ukraïns’ke mystetstvoznavstvo, 1967, no. 1

Demchenko, Evgeniia. Satiricheskaia pressa Ukrainy, 1905–1907 gg. (Kyiv 1980)

Sofiia Yaniv

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988).]