Horlivka

Horlivka [Горлівка]. Map: V-19, DB Map: DB DBIII-4. City (2020 pop 242,000) formerly under oblast jurisdiction in Donetsk oblast 40 km northeast of Donetsk, one of the most important anthracite-mining and industrial centers in the Donets Basin, on the Donets-Donbas Canal, and a major railway and minor highway junction. The railways lead south to Makiivka and Donetsk (triple-track, electrified), southwest to Dnipro (double-track, electrified), northwest to Kostiantynivka (double-track, electrified), north to Bakhmut (double-track, electrified), northeast to Popasna (single-track, electrified) and east to Debaltseve (triple-track, electrified). Major highways (Donetsk–Debaltseve–Luhansk, Kharkiv–Debaltseve–Antratsyt) bypass Horlivka to the south and east, respectively, alleviating the city of through traffic.

History. Horlivka is located on a gullied plain, in the headwaters of the Bakhmutka River (flowing north, into the Donets River), the Luhan River (flowing north, then east, into the Donets River), the Korsun River (flowing south into the Miius River), and the Zalizna Balka (flowing west into the northward flowing Kazennyi Torets River). Founded among the mid-18th century villages of Hosudariv Bairak, Korsun, Mykytivka, Zaitseve, and Zalizna Balka, Horlivka is named after a Russian mining engineer, Petr Gorlov, who built the first coal mine there in 1867. By the early 20th century the mining settlement had developed into an important industrial center. From 10,000 inhabitants in 1898, its population grew to 30,000 in 1916, 23,100 in 1926, and after becoming raion center in 1925 gained city status in 1932, and attained the population of 181,500 in 1939. Soviet industrialization expanded coal mining and added a coke-chemical plant (1928), a nitrogen fertilizer plant (1933, now the Styrol plant) and an explosives plant (1939).

Horlivka was devastated during the Second World War, but re-built, its water supply enhanced by the Donets-Donbas Canal (1954–8). By 1959 its population had grown to 308,000 (46 percent of which consisted of Ukrainians and 48 percent of Russians). Since 1970 its coal industry has not expanded (until then over 10 million t of coal was produced annually); consequently its population, having reached 335,000 in 1970, stagnated at 336,000 by 1979, resumed growth to reach 345,000 in 1987, but with more challenging coal production and ageing population began to decline: 338,000 (1989), 336,000 (1992), 292,250 (2001), 292,000 (2002), 264,000 (2010), 259,000 (2012), and 254,400 (2014). Since Ukraine’s independence, the ethnic make-up of the city shifted in favor of Ukrainians. According to the 2001 census, the city’s population was comprised of 51.4 percent Ukrainians, 44.8 percent Russians, 1.3 percent Belarusians, 0.3 percent Tatars, 0.3 percent Armenians, 0.2 percent Moldovans, and 0.2 percent Azeris. Privatization and foreign direct investment revived the economy. But in 2014 the city was taken by the pro-Russian forces and became part of the so-called ‘Donetsk People’s Republic.’ This had a severely negative impact on the socio-political life and the economy of the city.

Economy. Horlivka’s economy was based on the extraction and the processing of its mineral resources. Of Horlivka’s nine anthracite mines, several were among the largest in the Donets Basin: the Lenin, Kindrativka-Nova, Kocheharka (after its expansion in 1933), Komsomolets, and Gagarin mines. Also located there were five mineral-enrichment factories, a coke-chemicals plant (est 1928, expanded 1932–3), the Styrol chemicals trust (the largest chemical enterprise in Ukraine, established in 1933 to make nitrogen fertilizer by way of ammonia from coke gas), the Horlivka state chemical plant (acids, explosives for the military), and a rubber component-making plant, the Horlivka Machine-Building Plant (one of the largest coal-mining-machine manufacturers in the former USSR), the New Horlivka Machine-Building Plant (mining equipment), four mechanical repair plants (for mining equipment and vehicles), the Mykytivka mercury deposit and processing plant, the Mykytivka (at Holmivskyi) and the Panteleimonivka dolomite and refractory-materials plants. Its food industry (meat-processing industry, dairy industry, wine-making industry, and confectionery), clothing industry, cloth furnishings industry, woodworking industry, and building-materials industry were all well developed to support the needs of the urban population.

In the 1970s coal mining reached its apex and then began to decline. The chemical industry picked up the slack. With Ukraine’s independence the most prospective industries were privatized; four coal mines were closed. The state-run Mykytivka mercury combine operations were liquidated, and the enterprise restructured to protect coal mines from flooding and the Donets-Donbas Canal from erosion. The Horlivka state chemical plant was scaled back to civilian production, was no longer state-owned (2002), and then closed (2006) and destroyed (2014). The Horlivka Coke Chemical Plant was privatized (1994), re-furbished (2005) and linked with a network of client firms in Ukraine; the links were broken with hostilities of 2014. The Styrol chemical trust was privatized in 1995, and diversified into the production of generic drugs and vitamins (1996, to western standards). By 2013 it had four divisions: fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, polyethylene packaging, and IT servicing (including printer cartridges). The hostilities of 2014 forced the management to close the Styrol operations, the most viable and award-winning enterprise in the city.

Culture. Horlivka developed a significant educational and cultural infrastructure. Of its 4 postsecondary institutions from the Soviet period, 3 emphasized technology: the Horlivka Automobile Road Institute of the Donetsk National Technical University (established in 1959), the Horlivka Technical College of the Donetsk National University, and the Horlivka Technical College of the Donetsk Technical University. The exception was the Horlivka Institute of Foreign Languages (English and French; transferred from Bila Tserkva to Horlivka in 1954; in 2012 it became a branch of the Donbas State Pedagogical University; in 2014 evacuated to Bakhmut, Donetsk oblast). In the post-Soviet period two institutions appeared in Horlivka: a branch of the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management (established in Kyiv in 1989, its branch in Horlivka in 1998), and a branch of the Open International University of Human Development «Ukraine» (established in Kyiv in 1998, the Horlivka branch in 2004). There were 6 special secondary schools (see secondary special education), and 8 vocational-technical schools, some becoming colleges, like the Horlivka Building Trades Technical College, the Horlivka Food Industry Technical College, the Horlivka Machine-building College, and the Horlivka Medical College. The Ukrainian dissident poet, Vasyl Stus, taught here in School No. 23 in the early 1960s, but a proposal to memorialize him in 2011 was rejected by the city authorities.

Horlivka has an art museum, a history museum, the Horlivka Museum of Miniature Books, and three theaters. It also had a notable Ukrainian dance ensemble, ‘Hirnyk.’ Sports facilities include three stadiums, including the ‘Shakhtar,’ and several sports complexes. Horlivka had nearly 40 Russian-language newspapers, each sponsored by its enterprise; the official city newspaper was Kochegarka (the stoke-hole) (since 1919); the local Ukrainian-language newspaper, Spadshchyna (Heritage), began publishing in 1993.

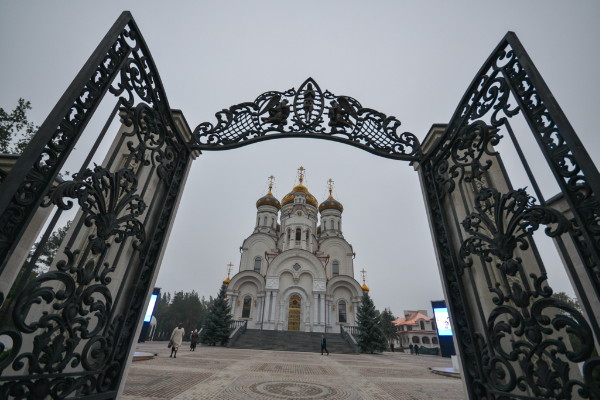

Church life functioned here during most of the Soviet period. The main church of Horlivka, Saint Nicholas’s (built 1893–1905 in Moderne style), worked until its closure in 1938, when its cross, dome and bell tower were removed and the building assigned to ‘Donbassenergo’; with German invasion and occupation during the Second World War, it was re-opened (1941), re-furbished by parishioners both inside and out (with a cone roof and cross) and, resisting renewed Soviet pressure (1958–64), remained open (one of several in Donetsk oblast), attracting faithful from the surrounding area; the bell tower was re-built (1990–1), the cone top replaced with a dome (1991); with Ukraine’s independence, the church was elevated to a cathedral status (1994), received copper roofing and gilded dome (2008–9). Other churches were built in the city, including a Roman Catholic chapel (2009).

City plan. Greater Horlivka (aka Horlivka Council, 2020 pop 259,000) is divided into three city raions: Central (extending to southwest and includes the town of Panteleimonivka, 2020 pop 8,000), Mykytivka (in the north, including the town of Holmivskyi, 2020 pop 7,000), and Kalinin (in the east). Its northwestern suburbs of Maiorsk and Zaitseve are in the front zone. On a map, the city forms an irregular shape with southwest and northeast prongs. It stretches 29 km from east to west and 28 km from north to south over built-up and open areas, covering 422 sq km. The built-up areas are separated by mine tailings, ponds and green spaces, extend 20 km east to west and 15 km north to south; the built-up area itself covers about 200 sq km.

The city center has most of the city’s institutional buildings. It is located in the central region, west of the main north-south thoroughfare and on the west side of the twin double-track north-south railway trunk line with its Horlivka passenger station. Its west end is defined by the Donets-Donbas Canal (here, a right-of-way with three surface wide-diameter siphon pipes) and along it, its filtration station. Its northern reach extends beyond Lenin Avenue and its south side transitions into mixed housing south of Pushkin Street.

The central showcase east-west arterial is the Victory Avenue. At its east end, on the south side, is the Soviet Army Square (a park with a Soviet Army tank); on the north side, a cardiology center, and a small square featuring a monument of Petr Gorlov; farther west, the Victory Square (a mini-park with a fountain) surrounded by 1950s apartment blocks. On the northwest corner of Victory Avenue and Dmytrov Boulevard is Lenin Square (with a large statue of Vladimir Lenin) and overlooking it is the Horlivka city hall. Dmytrov Boulevard leads south to the (1905) Revolution Square; nearby are the city’s youth creativity center and the Styrol Concert Hall. Southwest of this square is the Jubilee Park; southeast of it, at the west end of Kirov Street, is the Horlivka Automobile Road Institute of the Donetsk National Technical University, and at the east end, Saint Nicholas’s Cathedral. One street north, along Pushkin Street are the Horlivka Museum of Fine Arts and the Horlivka History Museum.

In the northern periphery of the city center, north of Lenin Avenue, at the railway tracks, is the Horlivka railway station and west of it, the Shakhtar Stadium and an extensive, wooded Gorky Park. On the north side of Lenin Avenue itself is the Kocheharka Palace of Culture, with a statue to Nikita Izotov (the first Stakhanovite); south of the avenue, the city’s central market; farther west, on the south side, is a medical center campus; south of it is a memorial park to the heroes of Horlivka: a Stella for the Soviet military, and a small memorial added after 1991 for the 17th-century Ukrainian Cossacks.

The factories, coal mines, processing plants, and quarries lie outside the city center. The closest, located across the railway tracks to the east but still within the Central raion, is the historic coal mine, Kocheharka. It was re-named affectionately from the original Gorlov’s ‘Korsun mine No. 1’ and expanded in 1933, but is now closed, its mound of tailings overgrown with shrubbery. North of Kocheharka, just east of the Horlivka train station and also within the Central raion, is the Horlivka Machine Building Plant. East of it is the Horlivka College of Industrial Technologies and Economics and next to it the Kirov Stadium.

In the Kalinin raion, 4 km east of the Horlivka train station, is the Styrol complex with its settling ponds; immediately to the east of it are the ruins of the State Chemical Plant; south of the Styrol complex is the New Horlivka Machine Building Plant (mine drilling and other equipment); and 2 km south southwest of the Styrol complex is the Haievyi Shaft and the adjacent Horlivka Coke Chemical Plant.

To the north, only 1.7 km from city hall, in the Central raion, is the Lenin coal mine; west of it, in the adjacent Mykytivka raion, are the Komsomolets, and Gagarin coal mines. Also in the Mykytivka raion, 4.5 km north of city hall, are two dolomite quarry pits and tailings and a closed mine. The Mykytivka Mercury Combine, 3 km west of the quarries and next to the front, is now in ruins. Other coal mines are: to the west, Yuzhnaia and Izotov (both close to the front, now in ruins), and to the east, in the Kalinin raion, Rumiantseve and Kalinin (still functional).

The front cuts across utilities and transportation lines. Water intake in the canal for the siphon pipes of the Donets-Donbas Canal is located at Druzhba, the northern suburb of Pivnichne (formerly Kirove), under Ukrainian government control. Electric power used to be supplied from the Vuhlehirsk Thermal Electric Power Station, 21 km north northeast of the Horlivka city center. Damaged from hostilities, it abuts the front on the Ukrainian government side; power now comes from Russia. Transportation to the north and west is cut off by the front. Within the city, urban transport is provided by streetcars (4 routes), trolleybuses (4 routes), and buses.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bondarenko, Ia. ‘Horlivka’ in Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukrainy (Kyiv 1989)

‘Horlivka: Plan mista’ 1:25,000 in Mista Ukrainy (Kyiv 2004)

Karta Horlivky, Donets'koi oblasti (2020) https://kartaukrainy.com.ua/Horlivka

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2020.]