Classicism

Classicism [Класицизм; klasytsyzm]. Drawing inspiration from the art, literature, and culture of classical antiquity of ancient Greece and Rome, classicism developed in the mid 18th century in western Europe (primarily in France and England) in opposition to the then-dominant Rococo esthetics. Generally, the classicist style was associated with harmony, restraint, and adherence to recognized ‘classical’ standards of form, beauty, and craftsmanship. It promoted such characteristics of a work of art or literature as symmetry, decorum, harmony, and idealism. This style was linked, on the one hand, with the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment, and, on the other hand, with the dominance of an imperial political order. Classicism came to Ukraine in the second half of the 18th century. Politically and culturally, this was the time of Ukraine’s national decline. The processes of Russification and colonization of Ukraine, resulting from the imperialist policies of the Russian empress Catherine II and the dissolution of the Cossack Hetman state, contributed to the denationalization of the potential leaders of Ukraine’s cultural life: the nobility and higher clergy. As a result, classicism never fully developed in Ukraine itself; virtually all of Ukrainian master artists of the classicist style worked and created in Saint Petersburg or Moscow.

Literature. In its broad sense the term refers to any kind of imitation of classical poetry; in its narrow sense, to a literary movement that arose in opposition to the baroque and worked out its own poetic norms, which included clarity of expression, the striving for ideal beauty, and strict adherence to certain rules or the imitation of certain models.

Classicism appeared in Ukraine in the mid-18th century. Its main examples are the travesties or parodies of N. Boileau and classical models. Although they are recognized by classicist poetics, travesties are considered to belong to a ‘low’ genre. During this period of national decline some Ukrainian classicists—I. Bohdanovych, Vasyl Kapnist, Vasilii Narezhny, and Vasyl H. Ruban—wrote exclusively in Russian. Some elements of classicism can be found in the school drama and school poetry of the 17th century and in Teofan Prokopovych's tragicomedy Vladimir (1705). After the versed travesties of the 18th century came the travesties by Ivan Kotliarevsky, Petro Hulak-Artemovsky, Pavlo Biletsky-Nosenko (‘Horpynyda’), Kostiantyn Dumytrashko (‘Zhabomyshodrakivka’), V. Dovhovych, Yakiv Kukharenko (‘Kharko’), and others. Poetry in a serious vein was written by P. Hulak-Artemovsky and Kostiantyn Puzyna (‘Oda’ [Ode], ‘Malorossiiskii krest’ianin’ [Little Russian Peasant]), as well as by early Ukrainian writers of fables. Kotliarevsky, Vasyl Hohol-Yanovsky, and Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko wrote plays. The highest achievement of Ukrainian classicism is the prose of Kvitka. The influence of Ukrainian classicism beyond Ukraine was insignificant and limited to the use of Ukrainian themes. Only Kotliarevsky's Eneïda (The Aeneid) served as a model for the uncompleted Belorussian Eneida of V. Dunin-Martsinkevich.

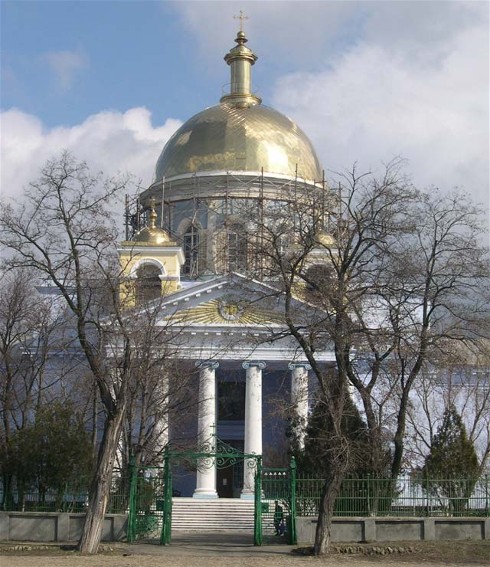

Art. In the art of the 18th century the term classicism denoted a certain general style connected with the esthtic ideals of classical Greek and Roman cultures and with works of art whose simplicity and severity of form contrasted with the decorativeness of the baroque. Classicism came to Ukraine from central and southern Europe in the mid-18th century. Its influence was felt first in Western Ukraine, where it manifested itself mainly in the architecture of palaces and villas; eg, the palace of the Ossolińskis in Lviv (now the Lviv National Scientific Library of Ukraine), built in 1827 by the Swiss architect P. Nobile; the palace in Vyshnivets (photo: Vyshnivets palace) in the Ternopil region, built in 1730–40; and the metropolitan's residence in Horodok (Lviv region), built in 1740. Later these kinds of buildings were built in central and eastern Ukraine by Italian, French, English, and German architects. One of the older monuments of palatial-villa architecture is the ensemble of buildings on the estates of A. Shydlovsky in the village of Merchyk in the Kharkiv region (photo: Merchyk palace). It was built in 1776–8 by Petro Yaroslavsky. The largest number of the finest examples of architectural classicism have been preserved in the Chernihiv region: the palace of Count Petro Zavadovsky in Lialychi designed by Giacomo Quarenghi in 1794–5; the villa in Khotyn, from the end of the 18th century; the villas in Stilne (built in 1797–9) and Ponurivka (built in 1804); the building of Mykhailo P. Myklashevsky in Nyzhnie (second half of the 18th century), V. Darahan's residence in Kozelets; the palaces of a patron of classicism, Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky, in Pochep (built in 1796 by Oleksii Yanovsky using designs by Jean-Baptiste Vallin de La Mothe) and in Baturyn (built in 1799–1803 according to the design of C. Cameron; photo: Baturyn palace); and the palatial complex of Count Petr Rumiantsev in the village of Kachanivka, built at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century (photo: Kachanivka palace). The classicist style was also embodied in numerous manor houses, churches, and town buildings throughout Ukraine. The most typical buildings of the 19th century in this style are the palaces in the village of Murovani Kurylivtsi (1805; photo: Murovani Kurylivtsi palace); the buildings of the Sofiivka Park near Uman (1796–1805); the palace in Samchyky in Podilia (photo: Samchyky palace); P. Galagan's palace in Sokyryntsi, designed by P. Dubrovsky in 1829 (photo: Sokyryntsi palace); the (no longer existing) buildings on the estates of the Kochubei family in the village of Dykanka in the Poltava region (photo: Dykanka palace); the church rotunda on Askoldova Mohyla in Kyiv, designed by Andrei Melensky in 1809–10 and destroyed by the Soviets; the Transfiguration Cathedral in Bolhrad in Odesa oblast, built in 1833–8; the Bezborodko Nizhyn Lyceum, designed by L. Rusca in 1824; the Kyiv University building, designed by Vincent Beretti in 1837–42 (photo: Kyiv University); the new building of the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, designed by Andrei Melensky in 1822–5; and the cathedral in Sevastopol, built in 1843. In these buildings classicism was often combined with the Empire style, which was closely related to it.

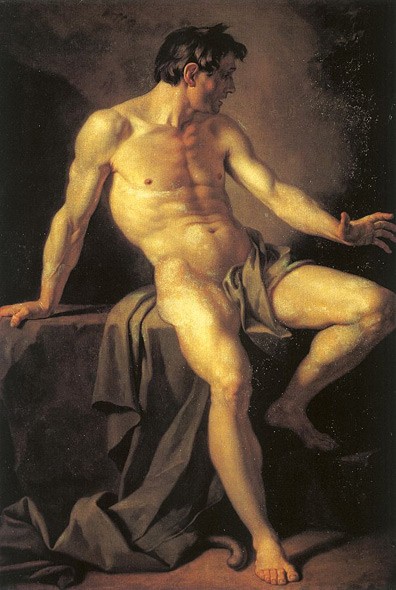

In sculpture classicism was represented by Ivan P. Martos and M. Kozlovsky, who worked in Saint Petersburg and Moscow and were the leading artists and teachers at the end of the 18th century, and by Kostiantyn Klymchenko, who worked in Rome. Ukrainian classicist painters had an important influence on the development of Russian painting; among these painters were Antin Losenko, who founded the historical school at the Russian Academy of Arts; Dmytro H. Levytsky, who was the leading portraitist of his time; and Levytsky's student Volodymyr Borovykovsky, who painted icons and portraits. All of them worked in Saint Petersburg. The masters of decorative painting, which was very typical of the period and was widely used in the palaces in Ukraine, were Hryhorii Stetsenko, Yu. Kozakevych, I. Kosarevsky, and the painter-serf M. Dykov. Vasilii Tropinin (a Russian who spent many years in Podilia), M. Terensky of Peremyshl, and Luka Dolynsky and I. Luchynsky of Lviv were realist painters of the classicist school. Classicism is reflected in the engravings of Hryhorii Srebrenytsky, M. Kozlovsky, and V. Borovykovsky and in the autolithographs of I. Shchedrovsky, P. Boklevsky, Kostiantyn Trutovsky, M. Mykeshyn, and others. In general, the works of the classicists are devoid of national traits. Classicism survived in Ukraine until the middle of the 19th century, when it turned into academism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zerov, M. Nove ukraïns’ke pys’menstvo, 1 (Kyiv 1924)

Holubets’, M. ‘Mystetstvo,’ in Istoriia ukraïns’koï kul’tury (Lviv 1937)

Zerov, M. Do dzherel, 2nd edn (Cracow 1943)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva. I: Arkhitektura (New York 1956)

Narys istoriï arkhitektury URSR (Kyiv 1957)

Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva v shesty tomakh, 4, bk 1 (Kyiv 1966)

Kyryliuk, Ie. et al (eds). Istoriia ukraïns’koï literatury u vos’my tomakh, 2 (Kyiv 1967)

Čyževs’kyj, D. A History of Ukrainian Literature (Littleton, Colo 1975)

Dmytro Chyzhevsky, Sviatoslav Hordynsky, Marko Robert Stech

[This article was updated in 2020.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)