Classical studies

Classical studies. With the introduction of Christianity from Byzantium (see Christianization of Ukraine), Ukraine became exposed to some extent to the cultural influence of ancient Greece. Translations of the Greek fathers of the church, chronicles, and excerpts from ancient philosophers that are scattered in collections such as the Pchela, show that the Greek language and culture were known in Ukraine. Povist’ vremennykh lit (Tale of Bygone Years) asserts that in 1037 Yaroslav the Wise translated Greek writing into Old Church Slavonic. It may be assumed that at the time certain elements of classical philology were studied in some monasteries. Latin was probably studied too. This is indicated by the well-known epistle in Latin from Prince Iziaslav Yaroslavych (1024–78) to Pope Gregory VII and by numerous Latin epistles from the popes to Ukrainian princes and bishops. Latin was used more widely in the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (on coins, in diplomacy, etc) than in Kyivan Rus’.

When Ukraine became a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a strong Latin current entered Ukrainian culture. Latin became the language of government, scholarship, education, and poetry, first in Galicia and from the 17th century in other regions as well. Consequently, interest in Roman literature and classical culture in general increased.

Western humanism, the religious polemical literature of the 16th century, and the studies of Ukrainian scholars at Western universities encouraged the study of ancient culture and the classical languages. Classical philology and philosophy, rhetoric, and poetics were important subjects of study at the Ostroh Academy (est 1577), brotherhood schools, and the Kyivan Mohyla Academy (est 1632). In some of these schools Latin was the language of instruction. Arsenii of Ellason, who published a Greek-Church Slavonic grammar, Adelphotes, in 1591, taught at the school of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood. These schools trained not only future theologians, but also secular leaders. The works of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Saint Augustine, and, from the end of the 17th century, of Erasmus were familiar to collegium students.

Classical philology attained a high level at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy in the 17th–18th century: problems of classical philosophy and Greek and Roman literature were researched by Diakovsky, and classical poetics and metrics were researched by Teofan Prokopovych, H. Slomynsky, and Mytrofan Dovhalevsky. In 1632 Eucharisterion, a collection of poetry imitative of classical models, was dedicated to Metropolitan Petro Mohyla. Classical themes were used in the sermons of Antin Radyvylovsky and Ioanikii Galiatovsky, among others. S. Charnkovsky (Charnetsky), the author of a text in rhetoric, was an expert on classical culture and Latin. Dymytrii Tuptalo, founder of the Latin college in Rostov and author of Basni ellinskii (a collection of Greek myths) and of the first Slavic-Ruthenian translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses with a commentary, was an authority on classical philology. T. Prokopovych made an important contribution to classical education in Ukraine. After studying Latin theology and classical philology in Rome, he returned to Kyiv in 1704 and thoroughly revised the Latin curriculum at the academy by introducing Western methods (among them, the direct imitation of such classical poets as Catullus, Ovid, and Horace). He provided models of the new methods in his Lucubrationes, particularly in the poem ‘Elegia Alexii,’ which is an imitation of Ovid’s ‘Tristia.’ In the 18th century Hryhorii Kozytsky taught Latin at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy (in 1758 he became professor of classical and West European literatures in Saint Petersburg).

The centralist policies of Catherine II and her heirs were detrimental to the development of classical philology in Ukraine. Nevertheless, the discipline retained its position in the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, Kharkiv University (est 1805), the Kremianets Lyceum (est 1819), and Kyiv University (est 1834). Some Ukrainian scholars (Hryhorii Kozytsky, R. Tymkovsky, M. Novosadsky, Fedir Zelenohorsky) taught classical studies in Russian schools, and most Ukrainian classical philologists published their works only in Russian (or Latin). The Odesa Society of History and Antiquities (1839–1922) investigated the ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast (Zakharii Arkas, V. Modestov, Serhii Dlozhevsky, and others). Studies in classical philology were basically directed towards narrow specialization in Greek epigraphy and partly towards the history of the Greek language. Some research was done on the history of Greek literature (A. Derevytsky, Fedir H. Myshchenko), Roman literature (V. Modestov, Mykola Sumtsov, S. Roslavsky-Petrovsky), classical philosophy (Petro Linytsky, Orest Novytsky), classical archeology and art (A. Dobiiash, Dmytro Yavornytsky), and ancient history (Yulian Kulakovsky, O. Pereiaslavsky). The popularity of classical philology in Russian-ruled Ukraine can be attributed to the fact that Latin and Greek were taught in gymnasiums and theological seminaries.

In Western Ukraine—Galicia and Bukovyna—the centers of classical philology were Lviv University and Chernivtsi University. Although the related disciplines were highly developed in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and both classical languages were taught and used in gymnasiums, social conditions and Polish influence did not allow Ukrainian classical philology to develop. Publications on ancient culture began to appear only with the foundation of the Shevchenko Scientific Society. In 1906–14 a commission of classical philology directed by Filaret Kolessa and Ostap Makarushka existed at the Shevchenko Scientific Society; its members included Ahenor Artymovych, Yaroslav Hordynsky, I. Demianchuk, V. Dyky, R. Ilevych, Spyridon Karkhut, Volodymyr Kmitsykevych, Yuliian Kobyliansky, Illia Kokorudz, Ivan Kopach, P. Mostovych, M. Posatsky, Osyp Rozdolsky, Mykola Sabat, Hryhorii Tsehlynsky, R. Tsehlynsky, and Vasyl Shchurat. Ivan Franko’s articles and translations of Greek lyric poetry and drama were an important contribution to classical philology.

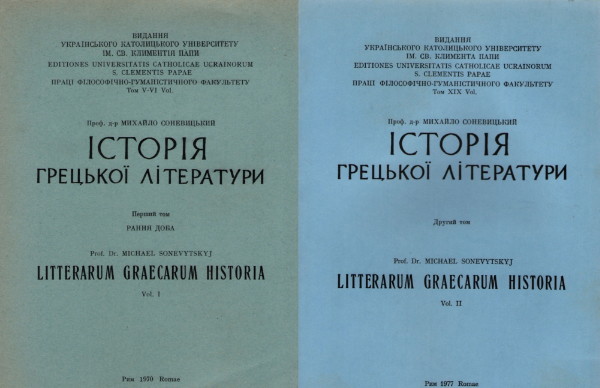

After the First World War the development of Ukrainian classical philology declined. In the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic it ceased to exist as a humanistic discipline. The teaching of classical languages was abolished and was resumed only in 1936 at a few universities for purely utilitarian purposes (in medicine and pharmacology) and partly for the needs of those studying ancient history and law. A few Ukrainian classical philologists (eg, Andrii Kotsevalov) at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR did research on the Greek and Roman relics on the Black Sea coast. Classical literature was assigned to institutes dealing with world literature. Oleksander Biletsky published some works on ancient literature. In Western Ukraine classical philology served the needs of education (tests, popular articles, translations). Besides several older scholars, M. Bilyk, Vasyl Stetsiuk, O. Dombrovsky, and Mykhailo Sonevytsky worked in the field of classical philology.

After the Second World War, the department of classical philology of the Lviv University continued to function and in 1962 began to publish Zbirnyk robit aspirantiv romano-hermans'koï i klasychnoï filolohiï (Collection of Graduate Student Papers on Romance, Germanic, and Classical Philology) and Visnyk: Seriia romano- hermans'koï i klasychnoï filolohiï (Herald: Romance, Germanic, and Classical Philology Series). Since 1959 it has been publishing Pytannia klasychnoï filolohiï (Questions of Classical Philology). The authorities put a stop to any attempts to re-establish departments or even chairs of classical philology at other universities.

Some classical philologists who emigrated worked at the Ukrainian Free University in Prague (Ahenor Artymovych, Fedir Sliusarenko), and then in Munich (Andrii Kotsevalov, Vasyl Stetsiuk).

Vasyl Stetsiuk

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]