Christmas

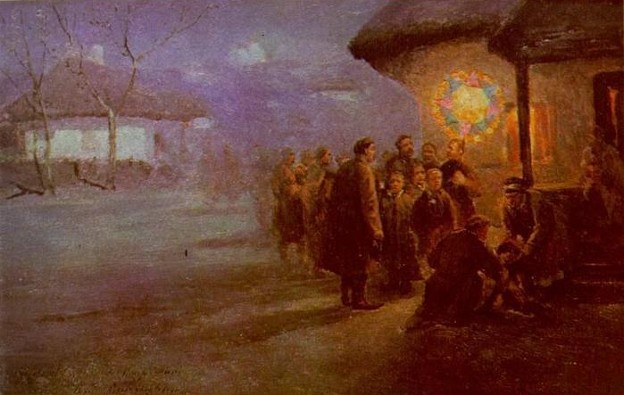

Christmas [Різдво; Rizdvo]. The feast of Christ’s birth was at first celebrated in the East on 6 January, together with the feast of Epiphany. Later, in the mid-4th century, it was established by the Roman Catholic church as a separate feast and was celebrated on 25 December according to the Julian calendar. With the introduction of Christianity into Ukraine in the 10th century Christmas was fused with the local pagan celebrations of the sun's return or the commencement of the agricultural year. In some areas the pre-Christian name of the feast—Koliada—has been preserved. The most interesting part of Ukrainian Christmas is Christmas Eve (Sviat-Vechir) with its wealth of ritual and magical acts aimed at ensuring a good harvest and a life of plenty. Dead ancestors and family members are believed to participate in the eve's celebration and are personified by a sheaf of wheat called did or didukh (grandsire) (see Ancestor worship). A characteristic feature of Christmas is caroling (koliaduvannia), which expresses respect for the master of the house and his children and is sometimes accompanied by a puppet theater (vertep), an individual dressed up as a goat (as part of the folk play Koza), and a handmade star. The religious festival lasts three days and involves Christmas liturgies (particularly on the first day), caroling, visiting, and entertaining relatives and acquaintances. The Christmas tree, which was adopted from Western Europe, is today an element of the New Year celebrations in Ukraine. The Christmas theme has an important place, more important than Easter, in Ukrainian painting, particularly church painting, and in poetry.

The ‘holy supper’ on Christmas Eve is a meal of 12 ritual meatless and milkless dishes. The order of the dishes and even the dishes themselves are not uniform everywhere, for every region adheres to its own tradition. In the Hutsul region, for example, the dishes were served in the following order: beans, fish, boiled potato dumplings (pyrohy or varenyky), cabbage rolls (holubtsi), dzobavka or kutia (cooked whole-wheat grains, honey, and ground poppy seeds), potatoes mashed with garlic, stewed fruit, lohaza (peas with oil or honey), plums with beans, pyrohy stuffed with poppy seeds, soup containing sauerkraut juice and groats (rosivnytsia), millet porridge, and boiled corn (kokot). (See also Traditional foods.)

Although there were regional variations, the rituals of Christmas followed a set pattern in former days. Except for the preparation of the ‘holy supper,’ all work was halted during the day, and the head of the household saw to it that everything was in order and that the entire family was at home. Towards the evening the head of the house went to the threshing floor to get a bundle of hay and a sheaf of rye, barley, or buckwheat; with a prayer he brought them into the house, spread the hay, and placed the sheaf of grain (the didukh) in the place of honor (under the icons). Hay or straw was strewn under and on top of the table, which the housewife then covered with a tablecloth. Garlic was placed at the four corners of the table while iron objects—an ax and a plowshare (or the plow itself)—and a yoke, a horse collar, or pieces of harness, were placed under the table. A pot of kutia was placed high up on the shelf in the corner of honor; the pot was topped with a loaf of bread (knysh) and a lighted candle.

The evening meal was accompanied by a special ceremony. When the kutia was served, the head of the house took the first spoonful, opened the window or went out into the yard, sometimes with an ax in his hand, and invited the ‘frost to eat kutia.’ On re-entering the house, he threw the first spoonful to the ceiling: an adhesion of many grains signified a rich harvest and augured a good swarming of bees. The head of the house then took some food from every dish and, placing it with some flour in a trough, carried it out to the cattle and gave it to them to eat. At the evening meal fortunes were told. After the meal three spoonfuls of each dish were placed on a separate plate for the souls of the dead relatives and spoons were left for them.

This ‘holy supper’ ritual and caroling are still observed, in a modified fashion, by Ukrainians in the diaspora. In Soviet Ukraine most Christmas rituals disappeared, but many of them have been revived in independent Ukraine, particularly in western oblasts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kylymnyk, S. Ukraïns’kyi rik u narodnykh zvychaiakh v istorychonomu osvitlenni, 1 (Winnipeg 1955)

Voropai, O. Zvychaï nashoho narodu, 1-2 (Munich 1958–66)

Ilarion, [Ohiienko, I.]. Dokhrystyians’ki viruvannia ukraïns’koho narodu (Winnipeg 1965)

Kurochkin, O. Novorichni sviata ukraïntsiv (Kyiv 1978)

Petro Odarchenko

[This article was updated in 2005.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)