Archipenko, Alexander

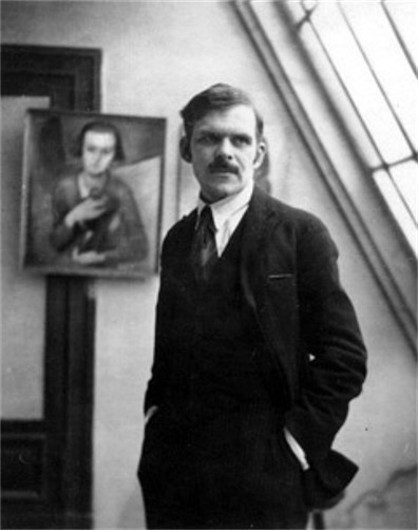

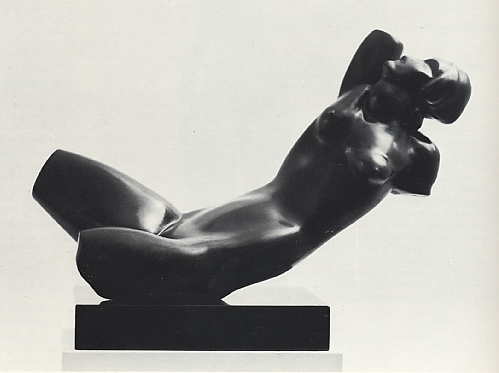

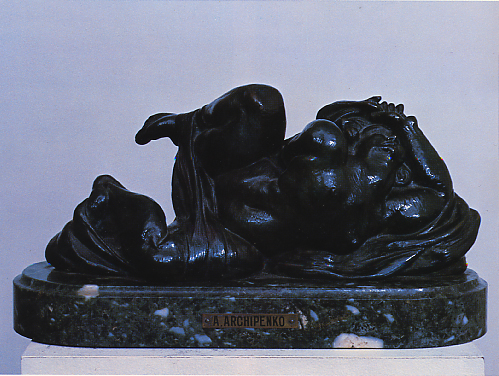

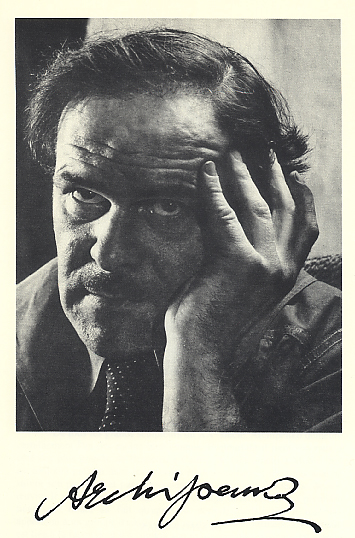

Archipenko, Alexander [Архипенко, Олександер; Arxypenko, Oleksander], b 30 May 1887 in Kyiv, d 25 February 1964 in New York. Modernist sculptor, painter, pedagogue, and a full member of the International Institute of Arts and Literature from 1953. Archipenko studied art at the Kyiv Art School in 1902–5, in Moscow in 1906–8 (photo: Archipenko in Moscow), and then briefly at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His first one-man show took place in 1906 in Ukraine. He moved to Paris in 1909. In 1910 he exhibited his works with a group of Cubists (see Cubism) at the Salon des Artistes Indépendants and then exhibited his works there annually until 1914 (photo: Repose [1912]). In 1911 his works appeared also at the Salon d'Automne. In 1912 Archipenko joined a new artistic group—La Section d'Or, which numbered among its members P. Picasso, G. Braque, J. Gris, F. Léger, R. Delaunay, R. de la Fresnaye, J. Villon, F. Picabia, and M. Duchamp—and participated in the group's exhibitions.

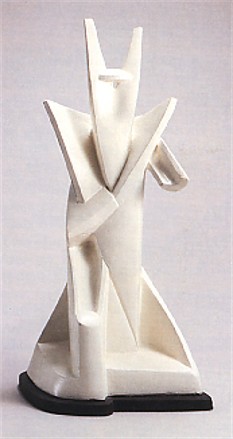

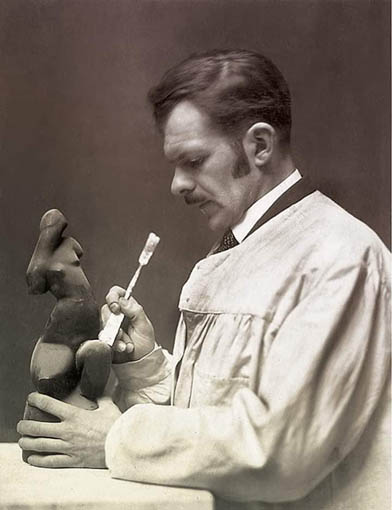

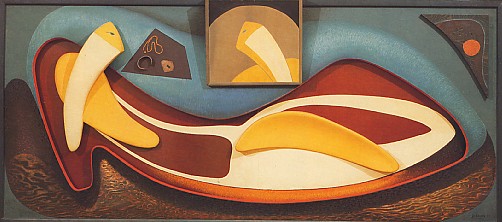

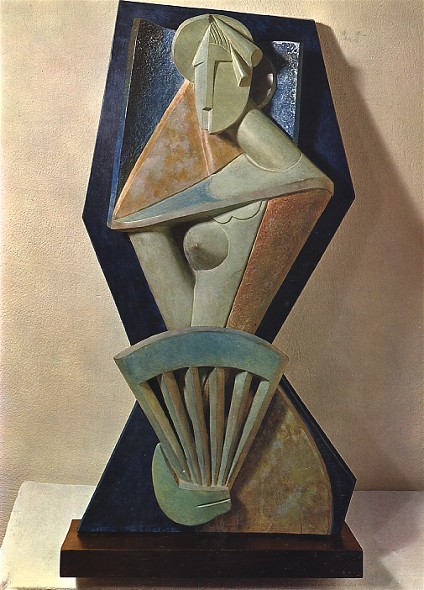

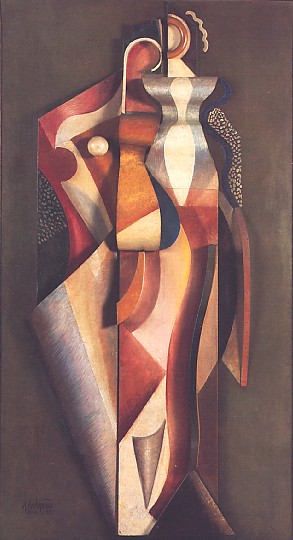

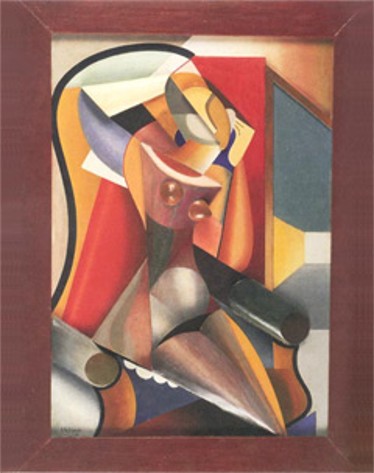

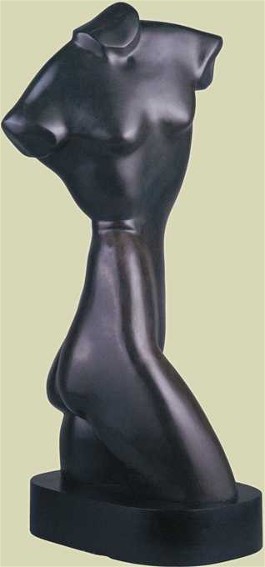

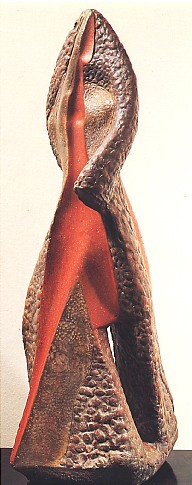

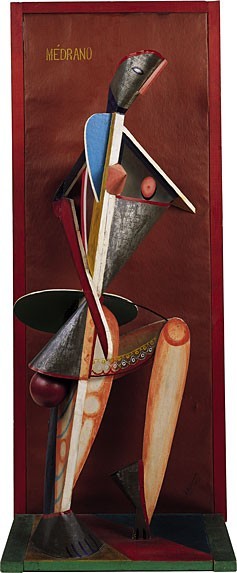

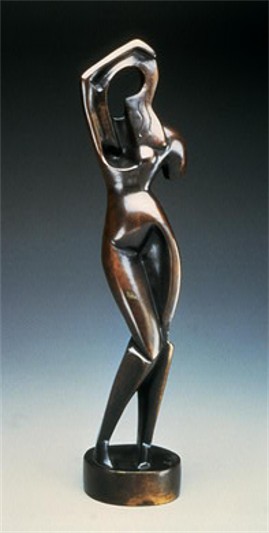

In 1912 Archipenko opened his own school of sculpture in Paris. At his individual exhibition at the Folkwang Museum in Hagen, Germany, in 1912, Archipenko displayed Médrano I, the first modern sculpture made of various polychromed materials (wood, glass, and metal fiber). It was followed by Médrano II (1913–14). At this time he also created the first so-called sculpto-peintures (carved and painted plaster reliefs, such as Woman before a Mirror [1916]) and the first modern sculpture composed of concave forms contrasted with convex ones and incorporating elements of color and the void—Walking Woman. In 1913 Archipenko’s works appeared at the Armory Show in New York, and he held his first individual exhibition at Galerie der Sturm in Berlin. In the following year he participated in a cubist exhibition in Prague and a futurist exhibition in Rome, and exhibited such works as Carrousel Pierrot and Boxing at Salon des Artistes Indépendants. During the First World War he lived in Cimiez near Nice, where, in 1917, he developed a cubist play, La Vie Humaine; he returned to Paris in 1918. From 1919 to 1921 Archipenko's works were exhibited in many cities throughout Europe. In 1920 he was given a separate pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and in 1920 and 1921 his work appeared at the exhibitions of La Section d'Or in Paris, Brussels, Geneva, Rome, and several cities in the Netherlands (photo: Archipenko's Woman [1920]). In 1921 Archipenko moved to Berlin, where he established a school of sculpture. He held a retrospective exhibition at Potsdam and his first individual exhibition in the United States, at the Société Anonyme in New York. (Photo: Archipenko's Turning Torso [1921].)

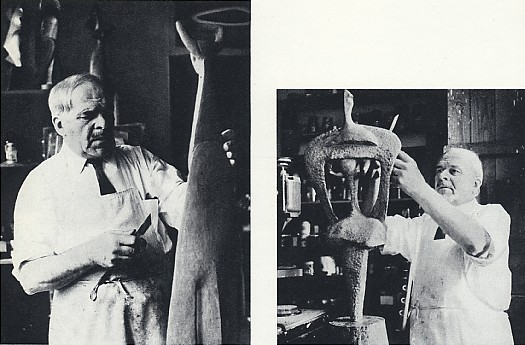

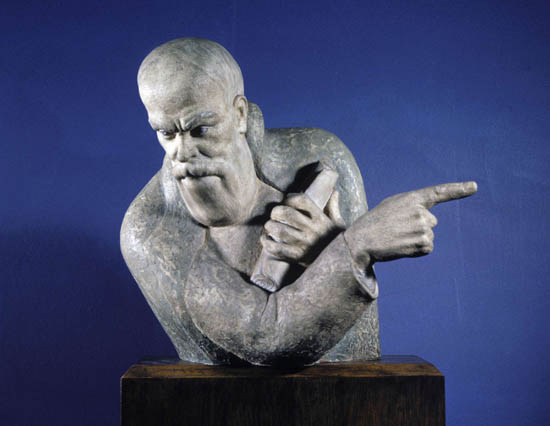

In 1923 Archipenko moved to the United States. He established a school in New York, and in the following year, he moved it to Woodstock, New Jersey. In 1927 he created and received a patent for changeable pictures (peinture changeante) known as Archipentura and Apparatus for Displaying Changeable Pictures. (Archipentura was lost in 1935.) Besides working at his art, Archipenko devoted much time to teaching. He was in constant contact with various universities, among them those in Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Chicago (the New Bauhaus School). In 1927 an exhibition of his works was arranged in Tokyo. In 1929 he established a school of ceramics, Arko, in New York. In 1933 his work appeared in the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. The Nazi regime confiscated 22 of Archipenko's sculptures in German museums in the 1930s. In 1937 he moved to Chicago, where he opened his Modern School of Fine Arts and Practical Design. In 1947 Archipenko created the first sculptures out of transparent materials (plastics) with interior illumination (modeling light)—l'art de la réflexion. In 1948 he exhibited his new plexiglass works at the Associated American Artists Galleries in New York. In 1952 and 1953 his work was exhibited in São Paulo, Brazil, and in Guatemala. In 1955 and 1956 his exhibitions toured Germany. In 1956 Archipenko tried his hand at moving figures (figures tournantes), which were mechanically rotating structures built of wood, mother of pearl, and metal. In 1959 he received the gold medal at Biennale d'Arte Trivenata at Padua, Italy. In 1960 his largest monograph, Fifty Creative Years, 1908–1958, appeared. Parts of it had been published previously in Ukrainian art journals. In 1962 Archipenko was elected to the Department of Art of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in the United States. His last works were two large bronzes, Queen of Sheba (1961) and King Solomon (1964) (photo: Archipenko working on King Solomon), and 10 lithographs entitled Les formes vivantes. In 1963 and 1964 large retrospective exhibitions of Archipenko's sculptures, drawings, and prints were held in Rome, Milan, and Munich. From 1967 to 1969 posthumous retrospective exhibitions of his work were organized by the University of California (Los Angeles) at 10 American museums and by the Smithsonian Institution at various European museums, including the Rodin Museum in Paris. In 1974 a large retrospective exhibition “Alexander Archipenko – A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture” took place in Tokyo, and was followed by numerous exhibitions in the United States and Europe.

As a cubist, Archipenko utilized interdependent geometrical lines and introduced new concepts and methods into sculpture. Juan Gris wrote about Archipenko’s influence on the art of the early 20th century: “Archipenko challenged the traditional understanding of sculpture. It was generally monochromatic at the time. His pieces were painted in bright colors. Instead of accepted materials such as marble, bronze or plaster, he used mundane materials such as wood, glass, metal, and wire. His creative process did not involve carving or modeling in the accepted tradition but nailing, pasting and tying together, with no attempt to hide nails, junctures or seams. His process parallels the visual experience of cubist painting.” Although cubism formed the basis of Archipenko’s art, it was not the only style he worked in. He himself referred to it in the following way: “As form my art, the geometric character of three-dimensional sculptures (e.g., Boxing, 1913, Gondolier, 1914) is due to the extreme simplification of form and not to Cubist dogma. I did not take from Cubism, but added to it.”

Archipenko's purpose was to discover the laws of formal relationships through a precise examination of the great historical styles and to preserve the old foundations of the plastic arts while transforming them in his own way. His creative and logical thought was also opposed to his dynamic personality, and this dramatic conflict endowed his art with an intriguing vitality.

Archipenko never severed his ties with his countrymen. During his first years in Paris he was a member of the Ukrainian Students' Club; in Berlin, a member of the Ukrainian Hromada; and in the United States, a member of the Ukrainian Artists' Association in the USA. His works appeared at the association's exhibitions. He belonged to the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Ukrainian Institute of America. Many of his works have Ukrainian themes, eg, the relief Ukraine (1940), four busts of Taras Shevchenko (photo: Archipenko's bust of Taras Shevchenko) (one of them in the Park of Nationalities in Cleveland), busts of Ivan Franko and Prince Volodymyr the Great, and portraits of Ukrainian public figures. Some of Archipenko's exhibitions, such as the one at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, were sponsored by Ukrainian groups.

In Soviet Ukraine Archipenko's name was never mentioned before his death. Five of his sculptures and paintings at the Lviv Museum of Ukrainian Art were destroyed in the 1950s. Although his name began appearing in the artistic press during the post-Stalin Thaw, Vitalii Korotych's monograph about him was suppressed. With the lessening of censorship and Party control during the perestroika period in the late 1980s, Archipenko quickly acquired recognition as one of Ukraine’s most prominent twentieth-century artists. The first Soviet book devoted to his works appeared in Kyiv in in 1989. The first exhibition of his works in post-Soviet Ukraine, entitled “Preserved in Ukraine,” took place in Kyiv in 2001.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goll, I. Archipenko – Album (Potsdam 1921)

Holubets', M. ‘Arkhypenko,’ Ukraïns'ke mystetstvo (Lviv 1922)

Hildebrandt, H. Alexander Archipenko (Berlin 1923; separate editions in English, German, French, Ukrainian, and later, Spanish)

Raynal, M. A. Archipenko (Rome 1923)

Wiese, E. Alexander Archipenko (Leipzig 1923)

Schacht, R. Alexander Archipenko. Sturm Bilderbücher (Berlin 1924)

Hordynsky, S. ‘The Art World of Archipenko,’ The Ukrainian Quarterly 11, no. 3 (1955)

Karshan, D.H. (ed). Archipenko, International Visionary (Washington, DC 1969)

Michaelsen, K.J. Archipenko: A Study of the Early Works, 1908–1920 (New York 1977)

Michaelsen, K.J. and N. Guralnik. Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute (Washington, D.C.–Tel Aviv–New York 1986)

Maslovs’ka, L.I. (ed). Oleksandr Arkhypenko: Al’bom (Kyiv 1989)

Barth, A. Alexander Archipenkos plastisches Oeuvre, 2 vols. (Frankfurt–New York 1997)

Sviatoslav Hordynsky, Marko Robert Stech

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%201952.jpg)