IEU'S FEATURED TOPICS IN UKRAINIAN CULTURE AND INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

I. The History and Cultural Legacy of the Kyivan Caves Monastery

II. The Historical Evolution of Ukrainian Law and Legal Tradition

III. Ukrainian Wandering Bards: Kobzars, Bandurysts, and Lirnyks

IV. Ostroh Academy: Eastern Europe's First Institution of Higher Learning

V. Brotherhoods: The Promoters of Education and Culture in Early Modern Ukraine

VI. The Origins and Tradition of Printing in Ukraine

VII. The Cultural Legacy of Kyivan Mohyla Academy

VIII. Ukrainian Music of the Baroque and Classical Periods

IX. The Tradition of Ukrainian Book Publishing

X. The History of Higher Education in Ukraine

XI. Higher Colleges and Lyceums in 18th- and 19th-Century Ukraine

XII. The Founders of Modern Ukrainian Historiography in the 19th Century

XIII. The Hromada Movement and the Growth of Ukrainian National Consciousness

XIV. Mykhailo Drahomanov and the First Ukrainian Political Program

XV. The Clandestine Brotherhood of Taras and Its Proto-Nationalist Program

XVI. The Ukrainian Populist-Ethnographic Theater in Russian-ruled Ukraine

XVII. Mykola Lysenko and the National School of Ukrainian Music

XVIII. Scholarly Societies in Ukraine in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

XIX. Ukrainian Literary and Scholarly Journals before 1914

XX. Ukrainian Composers in Western Ukraine before the Second World War

XXI. Les Kurbas, Berezil, and the Birth of Modern Ukrainian Theater

XXII. The Ukrainian Opera and Famous Ukrainian Opera Singers

XXIII. Modernist Music in Soviet Ukraine: The 1920s Generation

XXIV. Ukrainian Poetic Cinema

XXV. The Ukrainian Music of the Socialist Realist Period (1930s-1950s)

XXVI. Ukrainian Composers of the 1960s Generation

XXVII. Museums in Ukraine

XXVIII. The Ukrainian Academy of Sciences

I. THE HISTORY AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF THE KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY

I. THE HISTORY AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF THE KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY

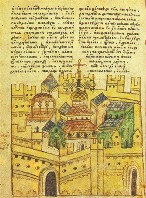

The Kyivan Cave Monastery was founded by Saint Anthony of the Caves in the mid-11th century near the village of Berestove on the outskirts of Kyiv. During the princely era of Kyivan Rus' the princes and boyars of Kyiv generously supported this monastery, donating money, valuables, and land, and building fortifications and churches. Many of the monks were from the educated, upper strata, and the monastery soon became the largest religious and cultural center in Kyivan Rus'. Rus' chronicles and other literary works were written there. Foreign books were translated there, transcribed, and illuminated. Architecture and religious art (icons, mosaics, frescoes)--the works of Master Olimpii, Deacon Hryhorii, and others--developed there. Many folk tales and legends eventually arose about its saintly figures and the miraculous construction of its main church, the Dormition Cathedral. The monastery was sacked several times, most devastatingly in 1240 during the Mongol invasion. But each time it was rebuilt, new churches were erected, and the underground tunnels of caves and catacombs expanded. In the late 16th century the monastery received stauropegion status from the Patriarch of Constantinople, freeing it from the control of the local metropolitan. By that time consisting of six cloisters, the monastic complex was designated a lavra--the term denoting an important monastery that came under the direct jurisdiction of the highest church body in a country. By the 18th century the Kyivan Cave Monastery had acquired a great deal of wealth. It owned 3 cities, 7 towns, 200 villages and hamlets, 70,000 serfs, 11 brickyards, 6 foundries, over 150 distilleries, over 150 flour mills, and almost 200 taverns. However, in 1786 the Russian government secularized its property and made it a dependent of the state. At the same time the custom of electing the council elders, its governing body, was abolished... Learn more about the history, architecture, and cultural legacy of the Kyivan Caves Monastery by visiting the following entries:

|

KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY. An important Orthodox monastery in Kyiv. In the mid-11th century the first monks, inspired by Saint Anthony of the Caves, excavated several caves and built a church above them. The monastery's first hegumen was Varlaam (until 1057). He was succeeded by Saint Theodosius of the Caves (ca 1062-74), who introduced the strict Studite rule. The main cultural and religious center of Kyivan Rus', the Kyivan Cave Monastery was one of the very few monasteries that managed to survive the Tatar devastation of the mid 13th century. After a period of non-activity the monastery was rebuilt in 1470 by Prince Semen Olelkovych. In 1615 Archimandrite Yelysei Pletenetsky established the first printing press in Kyiv at the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press, which became one of the most important center of publishing in Ukraine. Metropolitan Petro Mohyla restored and embellished the monastery. However, following the period of the Ruin and the subjugation of the Ukrainian Orthodox church by Moscow, in 1688 the monastery became directly subordinate to the Moscow patriarch. Its cultural influence was later severely undercut by the Russian government's 1720 prohibition on the printing of new books and the imposition of censorship on all publications... |

| Kyivan Cave Monastery |

KYIVAN CAVE PATERICON. A collection of tales about the monks of the Kyivan Cave Monastery. The original version arose after 1215 but not later than 1230 out of the correspondence of two monks of the monastery--monk Simon (by then the bishop of Suzdal and Vladimir) and monk Polikarp, who used the epistolary form as a literary device. The letters contain 20 tales about righteous or sinful monks of the monastery based on oral legends and several written sources. The later redactions, it seems, did not change the original text significantly, but supplemented it with several stories from the monastery's history. In 1635 the patericon was printed in Polish by Metropolitan Sylvestr Kosiv, and in 1661 in Ukrainian Church Slavonic. Because of its relatively simple style, particularly in monk Simon, and its rich vocabulary, as well as its masterly characterization of individuals by means of dialogue, prayer, and 'internal monologue,' the patericon is one of the outstanding works of Old Ukrainian literature. It marked an important advance in the literary art of the period... |

|

| Kyivan Cave Patericon |

KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY ICON PAINTING AND ART STUDIO. Main centre of Ukrainian icon painting for many centuries. Its founding at the Kyivan Cave Monastery at the end of the 11th century was connected with the painting (1083-9) of the Dormition Cathedral by Greek masters and the Kyivan artists Master Olimpii and Deacon Hryhorii. The studio developed a distinctive style that is evident in its frescoes, icons, and book illuminations, including the Kyiv Psalter of 1397. A major art school emerged at the monastery in the 17th century. It moved away from the Byzantine tradition of icon painting and adopted Western styles. Under the influence of master Oleksander Tarasevych, book engraving was given a prominent place in the school's curriculum. The studio's finest masterpieces of the 18th century are the mural paintings of the Dormition Cathedral and the Trinity Church above the Main Gate of the monastery. At one time, over 40 masters taught several hundred students (mainly from Ukraine, but also from the Balkan countries and Moldavia) at the studio. However, towards the end of the 18th century the studio began to gradually lose its importance in the development of Ukrainian art... |

|

| Kyivan Cave Monastery Icon Painting and Art Studio |

title page_s.jpg)

|

KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY PRESS. The first imprimery in Kyiv and the most important center of printing and engraving in Ukraine in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was founded ca 1606-15 at the Kyivan Cave Monastery by the archimandrite Yelysei Pletenetsky, who purchased the equipment of the former Striatyn Press of Hedeon Balaban in Striatyn, Galicia. Later it was headed by, among others, Zakhariia Kopystensky, Petro Mohyla, Innokentii Gizel (for over 30 years), Varlaam Yasynsky, and Yoasaf Krokovsky. The oldest extant book printed by the imprimery is the Horologion of 1616. The press issued several hundred titles on various subjects, both original works and translations, in Ukrainian, Church Slavonic, Polish, Russian, Latin, and Greek. Beautifully engraved and ornamented, these books were distributed throughout the Slavic countries, as well as Austria, Greece, and Moldavia. In the 16th and 17th centuries the imprimery played an important role in raising the level of education and culture in Ukraine and in aiding the Orthodox Ukrainians to defend themselves against the inroads of Polonization and Catholicism. But the tsarist ukase of 1720 limited it to printing only religious works, which it continued to do until 1918... |

| Kyivan Cave Monastery Press |

|

DORMITION CATHEDRAL OF THE KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY. The main church of the Kyivan Cave Monastery. Built in 1073-8 at the initiative of Saint Theodosius of the Caves during the hegumenship of Stefan of Kyiv and funded by Prince Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych. The cathedral consisted basically of one story built on a cruciform plan with a cupola supported by six columns. Inside, the central part was decorated with mosaics (including an Oranta), while the rest of the walls were painted with frescoes. According to the Kyivan Cave Patericon, Master Olimpii was to have been one of the mosaic masters. After many reconstructions these artistic works have been lost. At the end of the 11th century many additions to the cathedral were built, including Saint John's Baptistry in the form of a small church on the north side. In the 17th century more cupolas and decorative elements in the Cossack baroque style were added. The church was destroyed by the Soviets in 1941. As the Soviet Army retreated from Kyiv, mines were placed under the cathedral, and later it was blown up. The reconstruction of the cathedral began in 1998 and was completed in time for its reconsecration during the Ukrainian Independence Day ceremonies in August 2000... |

| Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Caves Monastery |

_s.jpg)

|

NATIONAL KYIVAN CAVE HISTORICAL-CULTURAL PRESERVE. An important historical preserve in Kyiv, consisting of the entire complex of the Kyivan Cave Monastery. The state-run preserve was organized in 1926, when the monastery was closed down by the Soviet authorities. In 1996 the complex was granted a national preserve status and assumed its present name. On its 28-ha grounds there are over 80 cultural and public structures, 37 of them architectural and historical monuments from the 11th to 18th centuries. The most important are the Great Bell Tower (1731-44), the Transfiguration Church in Berestove (early 12th century), the Trinity Church above the Main Gate (1108, restoration paid for by Hetman Ivan Mazepa in the early 18th century), and the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1078, destroyed by a Soviet mine in 1941, rebuilt in 1998-2000). The museums of the preserve contain many rare and valuable items from the 16th to 18th century: manuscripts, incunabula, and old books (many of them printed by the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press), and embroidery, precious metallic objects, engravings, printing blocks, and art works... |

| National Kyivan Cave Historical-Cultural Preserve |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with the history, architecture, and cultural legacy of the Kyivan Caves Monastery were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

II. THE HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF UKRAINIAN LAW AND LEGAL TRADITION

II. THE HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF UKRAINIAN LAW AND LEGAL TRADITION

Before states were formed, communities on Ukrainian territory were governed by customary law. The history of Ukrainian law is divided into periods according to the distinctive states that arose in Ukraine. In the Princely era (9th-14th centuries) the main sources of law were customary law, agreements such as international treaties, compacts among princes, contracts between princes and the people, princely decrees, viche decisions, and Byzantine law. The most original legal monument of the period is Ruskaia Pravda, which includes the principal norms of substantive and procedural law. The medieval Kyivan Rus' state declined, but its law continued to function. In the 14th to 15th centuries it was known as Rus' law in Ukrainian territories under Polish rule. Gradually, it was replaced by public as well as private Polish law. At the same time (14th-17th centuries) Lithuanian-Ruthenian law developed in Ukrainian territories within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The laws compiled in the Lithuanian Register and the Lithuanian Statute remained in force within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and, to some extent, in the Hetman state. The law of the Cossack period was based on the Hetman's treaties and legislative acts, the Lithuanian Statute, compilations of customary law and Germanic law, and court decisions. The autonomous Hetman state had its own law systematized in the Code of Laws of 1743. With the abolition of Ukrainian autonomy at the end of the 18th century, Russian law, first public and then civil, was introduced in Russian-ruled territories. In Western Ukraine, Austrian law was introduced in 1772-5... Learn more about the historical evolution of Ukrainian law by visiting the following entries:

|

LAW. The set of compulsory rules governing relations among individuals as well as institutions in a given society. Being part of the national culture, the law is influenced by the beliefs of a society and is inextricably involved in its social, political, and economic development. The term for law, pravo, originally meant 'judgment' or 'trial.' The original legal tradition developed on Ukrainian lands came to an end in the 18th century, when foreign Russian law was introduced in Russian-ruled territories. In Western Ukraine, Austrian law was introduced in 1772-5. Except for state and political laws, the laws of the former regimes remained in force during the brief period of Ukraine's struggle for independence (1917-20). Ukrainian legislators and jurists did not have time to construct an independent system of law. During the Soviet period legal norms were determined not only by the constitution and the laws or decrees of the government, but also by the Communist Party program and the current Party line. Thus, law was an instrument of politics. Attempts to de-politicize law and bring it closer to European standards have been made in independent Ukraine since 1991... |

| Law |

|

CUSTOMARY LAW (zvychaieve pravo; also known as the unwritten law). Norms of conduct that are practiced in society because they have been accepted for a long time and are regarded as obligatory. Customary law in Ukraine dates back to prehistoric times. In the Princely era legal relations were governed by customary law, which was eventually codified in Ruskaia Pravda. The decrees issued by the princes explicated customary law rather than creating new law. With the demise of Kyivan Rus' Ukrainian customary law continued to operate even under the Tatars, who did not interfere in the internal affairs of their conquered territories, and then under Polish hegemony. The norms of Ukrainian customary law were preserved under Lithuanian rule and were codified in the Lithuanian Statute, which to a large extent, particularly in respect to civil, criminal, and procedural norms, was based on ancient Ukrainian customary law. In the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state the community courts were a judicial institution based on customary law. They continued to operate in the Cossack period, but their importance gradually diminished...

|

| Customary law |

|

RUSKAIA PRAVDA (Rus' Truth [Law]). The most important collection of old Ukrainian-Rus' laws and an important source for the study of the legal and social history of Rus'-Ukraine and neighboring Slavic countries. It was compiled in the 11th and 12th centuries on the basis of customary law. The original text has never been found, but there are over 100 transcriptions in existence from the 13th to 18th centuries. There are three redactions of Ruskaia Pravda, the short, expanded, and condensed versions. The expanded redaction, consisting of 121 articles, was the most widespread. In the criminal law of the expanded redaction blood vengeance was replaced by monetary fines and state penalties. Serious crimes, such as horse stealing, robbery, and arson, were punished by banishment and seizure. With the exception of the most privileged strata in the society, all free citizens were protected by the code. Its main purpose was to provide individuals with the power to defend their right to life, health, and property and to provide courts with the basis for a fair judgment. A characteristic feature of Ruskaia Pravda is its evolution toward a more humane law system... |

| Ruskaia pravda |

|

LITHUANIAN-RUTHENIAN LAW [Lytovs'ko-Rus'ke pravo]. The system of law of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state or, more precisely, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which from the 14th to the 18th century included Lithuania, Belarus, and most of Ukraine (to the Union of Lublin in 1569). The Lithuanian-Ruthenian law was initially based on Ruskaia Pravda and later on the Lithuanian Statute as well as Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian customary law. The systematic study of Lithuanian-Ruthenian law began in the first half of the 19th century. Polish historians considered it a local variant of Polish law, and Russian historians usually referred to it as 'western Russian' law and treated it as part of Russian law. Eventually, it was studied by Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian historians and legal scholars, who accepted it as part of the legal history of all three nations... |

| Lithuanian-Ruthenian Law |

|

LITHUANIAN STATUTE. The code of laws of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state, published in the 16th century in three basic editions. It was one of the most advanced legal codes of its time. The overriding concern of the First or Old Lithuanian Statute (1529) was to protect the interests of the state and nobility, especially the magnates. The Second Lithuanian Statute (1566), often called the Volhynian version because of the influence of the Volhynian nobility in its preparation, brought about major administrative-political reforms and expanded the privileges of the lower gentry. In the Third Lithuanian Statute (1588) many Polish concepts were introduced into the criminal and civil law, which were systematized anew. All three editions of the Lithuanian Statute were written in the contemporary Ruthenian chancellery language, which was a mixture of Church Slavonic, Ukrainian, and Belarusian. The Lithuanian Statute remained for several centuries the basic collection of laws in Ukraine. It was the main source of Ukrainian law for the Cossack Hetman state and the basic source of the Code of Laws of 1743. In Right-Bank Ukraine it remained in force until 1840, when it was annulled by Tsar Nicholas I... |

| Lithuanian Statute |

|

CODE OF LAWS OF 1743. Collection of prevailing Ukrainian laws in the Cossack Hetman state. The Russian government never ratified the code of laws, and hence it remained only a proposal, although it became the basic source of operative law in Ukraine in the 17th and 18th centuries. The code of laws was prepared by the committee composed of representatives of the higher clergy, Cossack officers, and municipal administrators. The main sources of the code were the Lithuanian Statute and the compilation of the Germanic law (Magdeburg law and Kulm law). In addition, hetman manifestos, Cossack court practice, and Ukrainian customary law were drawn on. In cases where no relevant law existed in the code, the code prescribed the use of other 'Christian' laws (law of analogy), court precedents, and customary law. The creative work of the committee consisted of the selection of quotes from written sources, their partial modification, and the incorporation of amendments to them. The prescriptions of criminal law reflected the severity of ancient law, moderated by the right of the court to reduce prescribed punishment 'according to circumstances of the case' and 'the severity of the crime'... |

| Code of Laws of 1743 |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the historical evolution of Ukrainian law and legal tradition were made possible by the financial support of ARKADI MULAK-YATSKIVSKY of Los Angeles, CA, USA.

III. UKRAINIAN WANDERING BARDS: KOBZARS, BANDURYSTS, AND LIRNYKS

III. UKRAINIAN WANDERING BARDS: KOBZARS, BANDURYSTS, AND LIRNYKS

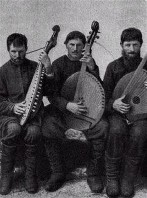

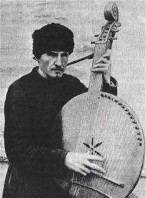

The artistic tradition of Ukrainian wandering bards, the kobzars (kobza players), bandurysts (bandura players), and lirnyks (lira players) is one of the most distinctive elements of Ukraine's cultural heritage. While kobzars first emerged in Kyivan Rus', bandurysts and lirnyks appeared and became popular in the 15th century. Kobzars often lived at the Zaporozhian Sich and accompanied the Cossacks on military campaigns. The epic songs they performed served to raise the morale of the Cossack army in times of war, and some (eg, Prokip Skriaha) were even beheaded by the Poles for performing dumas that incited popular revolts. As the Hetman state declined, so did the fortunes of the kobzars, and they gradually joined the ranks of mendicants, playing and begging for alms at rural marketplaces. In the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly from the 1870s, the kobzars, including the virtuoso Ostap Veresai, were persecuted by the tsarist regime as the propagators of Ukrainophile sentiments and historical memory. In the 1930s, during Stalin's Great Terror, several hundred kobzars and lirnyks were brought to a congress from all parts of Ukraine and after the congress ended almost all of them were shot... Learn more about the artistic legacy of the Ukrainian wandering bards by visiting the following entries:

|

KOBZARS. Wandering folk bards who performed a large repertoire of epic-historical, religious, and folk songs while playing a kobza or bandura. Kobzars originally composed and performed their own historical songs and dumas in the recitative style and later added songs of various other genres (religious and humorous songs, dance melodies) to their repertoires, which were passed on to their students. Kobzars were held in high esteem by the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In the late 18th century the occupation of kobzar became the almost exclusive province of the blind and crippled, who organized kobzar brotherhoods to protect their corporate interests. In the 19th century, the few hundred remaining kobzars in Poltava, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv gubernias and their artistry aroused the interest of various ethnographers, composers, and painters, including Mykola Lysenko, Oleksander Rusov, and Lesia Ukrainka... |

| Kobzars |

|

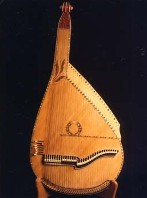

BANDURA. A Ukrainian musical instrument similar in construction and appearance to a lute. The bandura has 32-55 strings: the 8-14 bass strings (bunty) are stretched along the neck, and the 24-43 treble strings (prystrunky) run along the side of the soundboard. Before the 20th century the bandura had various shapes and tunings (basically diatonic), but in recent times it has been standardized. The oldest record of a bandura-like instrument in Ukraine is an 11th-century fresco of court musicians (skomorokhy) in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. This lute-like instrument is probably the ancestor of the bandura and the kobza. The two instruments were related, but distinct. The kobza was smaller in size and had fewer strings, but these were fretted. Around the 16th century prystrunky were added to the bandura, and from that time only one note was obtained from each string... |

| Bandura |

|

DUMA. Lyrico-epic works of folk origin about events in the Cossack period of the 16th-17th century. The dumas differ from other lyrico-epic and historical poetry by their form and by the way in which they were performed. They did not have a set strophic structure, but consisted of uneven periods that were governed by the unfolding of the story. Each period constituted a finished, syntactical whole and conveyed a complete thought. The dumas were not sung, but were performed in recitative to the accompaniment of a bandura, kobza, or lira. The chanting had much in common with funeral lamentation. Scholars connect the dumas with the poetic forms that appeared in Ukraine in the 12th century, particularly with the Slovo o polku Ihorevi. One widely accepted theory of the origin of the dumas is that proposed by Pavlo Zhytetsky, according to which they were a unique synthesis of popular and 'bookish-intellectual' creativity... |

| Duma |

|

LIRNYKS. Wandering folk minstrels, often blind, who accompanied themselves on a lira, a folk string instrument introduced in Ukraine from the West in the 15th century. The sound of a lira is produced by cranking a rosined wheel against strings within the instrument. Most frequently, the lira has three strings; the two lower strings are monotonic, and the higher string leads the melody. Lirnyks appeared in Ukraine in the 15th century and had formed a guild by the end of the 17th century. There were special schools for them. Their repertoire consisted mainly of religious songs, although humorous and satirical songs were also popular. Some lirnyks specialized in historical songs and dumas. The lifestyle of lirnyks (as well as kobzars) is described by N. Kononenko in Ukrainian Minstrels: And the Blind Shall Sing (1998)... |

| Lirnyks |

|

VERESAI, OSTAP, b 1803 in Kaliuzhyntsi, Pryluka county, Poltava gubernia, d April 1890 in Sokyryntsi, Pryluka county, Poltava gubernia. Kobza player and singer (tenor). A peasant who became blind in his early youth, he studied from 1818 with S. Koshovy and other kobzars. By the 1860s he was the most renowned performer of Ukrainian epic and historical songs. In 1873 he appeared in recital for the Southwestern Branch of the Imperial Russian Geographic Society and in 1875 concertized in Saint Petersburg. His repertoire included the dumas Kinless Fedir, Three Brothers from Azov, and Oleksii Popovych. Veresai's artistry was studied by ethnographers such as Oleksander Rusov and Pavlo Chubynsky, as well as by Mykola Lysenko, who wrote a monograph on the works in Veresai's repertoire (1873, 1978)... |

| Ostap Veresai |

|

PARKHOMENKO, TERENTII, b 28 October 1872 in Voloskivtsi, Sosnytsia county, Chernihiv gubernia, d 23 March 1910 in Voloskivtsi. Kobzar. Having lost his sight at 10 he studied the kobza under A. Hoidenko and others and then for five years wandered with Hoidenko through Ukraine. At 30 he began to teach the kobza. Some of his students (Petro Tkachenko-Halashko, Serdiuk-Pereliub, and Avram Hrebin) became noted folk singers. He corresponded with Mykola Lysenko, Opanas Slastion, Oleksander Malynka, Mikhail Speransky, Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko, and Volodymyr Hnatiuk. He gave concerts in Kyiv, Poltava, Nizhyn, Mohyliv-Podilskyi, Uman, Vinnytsia, Yelysavethrad, and Warsaw. His repertoire included dumas, historical songs, psalms, lyrical songs, and satires. Because his songs awakened national consciousness among the peasants, he was harassed by the authorities. He died as a result of a police beating... |

| Terentii Parkhomenko |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the Ukrainian wandering bards were made possible by a generous donation from ARKADI MULAK-YATSKIVSKY of Los Angeles, CA, USA.

IV. OSTROH ACADEMY: EASTERN EUROPE'S FIRST INSTITUTION OF HIGHER LEARNING

IV. OSTROH ACADEMY: EASTERN EUROPE'S FIRST INSTITUTION OF HIGHER LEARNING

Founded ca 1576 in Ostroh, Volhynia, by a Ukrainian nobleman Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky--one of the most remarkable figures in the 16th-century Ukrainian cultural and national rebirth--the Ostroh Academy was the first postsecondary learning center in the Orthodox Eastern Europe. At a time when Catholicism was making inroads into Western Ukraine, the academy was a bastion of Orthodoxy and Ruthenian culture and maintained the traditional orientation toward Constantinople. Though the Ostroh Academy did not develop into a Western European-style university, as Ostrozky had hoped, it was the foremost Orthodox academy of its time. Closely associated with the Ostroh Press, the academy and the Ostroh intellectual circle had an enduring influence on pedagogical thought and the organization of schools in Ukraine and provided a model for the brotherhood schools that were later founded in Lviv, Lutsk, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Vilnius, and Brest. The legacy and tradition of the Ostroh Academy has endured until today and became the basis for the establishment in 1994 of the Ostroh Higher Collegium, which was conferred university status in 2000 and renamed the Ostroh Academy National University... Learn more about the Ostroh Academy and Ostroh intellectual circle by visiting the following entries:

|

OSTROH ACADEMY. The first rector of the academy was the writer Herasym Smotrytsky. The instructors, many of whom had been invited from Constantinople, included the pseudonymous Ostrozkyi Kliryk, the Greek Cyril Lucaris, J. Latos (a philosopher from Cracow University), and Yov Boretsky, who later became rector of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School and then metropolitan of Kyiv. The curriculum consisted of Church Slavonic, Greek, Latin, theology, philosophy, medicine, natural science, and the classical free studies (mathematics, astronomy, grammar, rhetoric, and logic). In addition the academy was renowned for choral singing. The academy was closely affiliated with the Ostroh Press. Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, the writer and scholar Meletii Smotrytsky, and several other prominent political and cultural leaders studied at the academy. With the founding of a rival Jesuit college in Ostroh in 1624, the academy went into decline, and by 1636 it had ceased to exist... |

| Ostroh Academy |

|

OSTROZKY, KOSTIANTYN VASYL, (Polish: Ostrogski, Konstantyn), b 1526 or 1527 in Dubno, Volhynia, d 23 February 1608 in Ostroh, Volhynia. Ukrainian nobleman and political and cultural figure; starosta of Volodymyr-Volynskyi and marshal of Volhynia from 1550, voivode of Kyiv from 1559, and senator from 1569; the most powerful magnate in Volhynia and one of the most influential figures in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was a candidate for the Polish throne after the death of Sigismund II Augustus (the last member of the Jagiellon dynasty) in 1572, and for the Muscovite throne after the death of Tsar Fedor Ivanovich (the last member of the Riurykide dynasty) in 1598. Ostrozky defended Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian) political rights and was the de facto leader of Ukraine in the negotiations leading up to the 1569 Union of Lublin, during which he demanded that Ruthenia be treated as an equal partner of Poland and Lithuania... |

| Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky |

|

SMOTRYTSKY, HERASYM, b ? in Smotrych (now in Dunaivtsi raion, Khmelnytskyi oblast), d October 1594. Writer and teacher; father of Meletii Smotrytsky. He was secretary at the Kamianets-Podilskyi county office and in 1576 was invited by Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky to Ostroh, where he became one of the leading activist members of the Ostroh intellectual circle. In 1580 Smotrytsky became the first rector of the Ostroh Academy. He was one of the publishers of the Ostroh Bible, to which he wrote the foreword and the verse dedication to Prince Ostrozky. The dedication is one of the earliest examples of Ukrainian versification (nonsyllabic) and is somewhat reminiscent of Ukrainian dumas. Smotrytsky's polemical works against those betraying the Orthodox faith and a satire on the clergy have been lost. Only his book, Kliuch tsarstva nebesnoho (Key to the Heavenly Kingdom, 1587), which is the first printed example of Ukrainian polemical literature, has survived... |

| Herasym Smotrytsky |

|

OSTROH PRESS. The second oldest printing press in Ukraine, founded in 1578 by Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) with the financial backing of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky at the prince's castle in Ostroh, Volhynia. Its first publications were Azbuka (Alphabet, 1578), a collection of prayers in Greek and Church Slavonic; the second impression of Fedorovych's Bukvar (1578), the first Ukrainian primer; the first Ukrainian edition of the New Testament and an alphabetical index to it (1580); the Ostroh Bible (1581); and the first poetic work printed in Cyrillic, Andrii Rymsha's Khronolohiia (Chronology, 1581). It also printed pro-Orthodox, anti-Uniate polemical literature, including works by Herasym Smotrytsky, V. Surazky, Ostrozky, Khrystofor Filalet, and the pseudonymous Ostrozkyi Kliryk; a book (1598) containing eight epistles by Meletios Pegas and one by Ivan Vyshensky (his only work published during his lifetime); several liturgical books; and works by Saint Basil the Great and Saint John Chrysostom in Church Slavonic translation... |

| Ostroh Press |

|

OSTROH BIBLE. The first full Church Slavonic edition of the canonical Old and New Testaments and the first three books of the Maccabees, printed in Ostroh in 1580-1 by Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) in 1,500-2,000 copies. The preparation of the text and the printing were funded by Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky. With close to 1,400 headpieces, initials, and tailpieces, the 628-folio book is one of the finest examples of printing in late 16th-century Ukraine. The text was based on all the Church Slavonic and Greek sources of the Bible (including the complete 1499 Bible of Archbishop Gennadii of Novgorod the Great) collected by Ostrozky. The Old Testament sources were verified against the Septuagint or translated anew (sometimes incorrectly) by scholars directed by Herasym Smotrytsky at the Ostroh Academy. The Bible includes Ostrozky's and Smotrytsky's prefaces, Smotrytsky's heraldic verses dedicated to Ostrozky, and Fedorovych's postscript. The Bible was reprinted with minor revisions in a unified orthography in Moscow in 1663... |

| Ostroh Bible |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries dealing with the Ostroh Academy and Ostroh intellectual circle were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

V. BROTHERHOODS: THE PROMOTERS OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE IN EARLY MODERN UKRAINE

V. BROTHERHOODS: THE PROMOTERS OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE IN EARLY MODERN UKRAINE

Starting in the late 16th century, the Orthodox lay brotherhoods, affiliated with individual church parishes in Ukraine, began to play a historical role in the development of Ukrainian culture and education. Such Orthodox brotherhoods came into existence only in Ukraine and Belarus and, to a large extent, their influence shaped the unique place Ukrainian culture and society have occupied between Eastern and Western Christianity. Although structurally similar to their western European counterparts, the Eastern-rite brotherhoods developed their unique features and their activities coincided with a period of crucial social and cultural change in early modern Ukraine. The Ukrainian brotherhoods assumed the task of defending the Orthodox faith and Ukrainian nationality by counteracting Catholic and particularly Jesuit expansionism, Polonization, and later conversion to the Uniate church. Because they consisted predominantly of burghers, the brotherhoods acquired a secular character and often found themselves in opposition to the authoritarian practices of the clergy. Hence, they endeavored to reform the Orthodox church from within by condemning the corrupt practices of the hierarchy and of individual clergymen. The brotherhoods brought about a revival in the life of the church by promoting cultural and educational activity. They founded brotherhood schools, printing presses, and libraries. The resulting cultural-religious movement found its literary expression in polemical literature. The brotherhoods also participated in civic and political life and maintained ties with the Cossacks. The schools attached to the Orthodox brotherhoods in several larger cities disseminated European humanist ideas and introduced generally accessible post-humanist education, while the brotherhood presses promoted the development of scholarship and literature... Learn more about the brotherhoods and their crucial influence on education and culture in early modern Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

|

BROTHERHOODS. Fraternities affiliated with individual churches in Ukraine and Belarus that performed a number of religious and secular functions. The origins of brotherhoods can be traced back to the medieval bratchyny, which were organized at churches in the Princely era. Brotherhoods as such appeared in Ukraine in the mid-15th century, with the rise of the burgher class. They adopted their organizational structure from Western medieval brotherhoods (confraternitates) and trade guilds. Initially the brotherhoods engaged only in religious and charitable activities. They maintained churches and sometimes assumed financial responsibility for them. However, in the second half of the 16th and at the beginning of the 17th century, the brotherhoods began to play a historical role. The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood was one of the oldest and most successful brotherhoods. In the late 16th and early 17th century new brotherhoods were founded and existing ones were reorganized in the towns of Galicia, the Kholm region, Podlachia, Volhynia, and the Dnipro region. Each brotherhood had its own statute (articles, regulations, procedures), modeled on the statute of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood of 1586. Although brotherhood members were usually merchants and skilled tradesmen residing in the towns, some Orthodox clerics, nobles and magnates, such as Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, participated in the affairs of certain brotherhoods. In 1620, Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, 'with the entire Zaporozhian Host,' joined the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood... |

| Brotherhoods |

|

BROTHERHOOD SCHOOLS. Schools founded by religious brotherhoods for the purposes of counteracting the denationalizing influence of Catholic (Jesuit) and Protestant schools and of preserving the Orthodox faith began to appear in the 1580s. The first school was established in 1586 by the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood. The school served as a model for other brotherhood schools in various towns of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of them in Ukraine and Belarus. In the first half of the 17th century even some villages had brotherhood schools. The most prominent schools were the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School and Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School. At first the brotherhood schools had a Greek-Church Slavonic curriculum: lectures were in Church Slavonic, and Greek was taught as a second language. Then the schools began to adopt the structure and curriculum of the Jesuit schools, using Latin as the primary language, particularly those schools that modeled themselves on the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. Ukrainian was used only for examination purposes and, from 1645, for teaching the catechism. Brotherhood schools were open to various social strata. Students were judged not by lineage, but by achievement (in contrast to Jesuit schools). Brotherhood schools made a significant contribution to the growth of religious and national consciousness and the development of Ukrainian culture... |

| Brotherhood schools |

|

LVIV DORMITION BROTHERHOOD. An Orthodox religious association founded in the 15th century by Lviv merchants and tradesmen at the Dormition Church in Lviv. It is the oldest and one of the leading Ukrainian brotherhoods, and it served as an example to other brotherhoods. There are historical references to it dating back to 1463. According to its charter, which was confirmed by Patriarch Joachim V of Antioch in 1586 and Patriarch Jeremiah II of Constantinople in 1589, the brotherhood was independent of the local bishops (right of stauropegion) and subject directly to the Patriarch of Constantinople. It had the right to oversee the activities not only of secular members of the church but also of the clergy and even the bishops. Its membership was open to all estates and to Orthodox believers from other cities and countries. Membership dues, profits from book sales, donations, and gifts were used to support the Dormition Church and Saint Onuphrius's Church and Monastery, which were owned by the brotherhood, and to operate a printing press, school, orphanages, hospitals, and homes for elderly members. As the leading cultural and religious institution for Western Ukraine, the Lviv brotherhood played a key role in resisting Polish national and religious oppression and in fighting for equality with the Catholics and the Polish burghers... |

| Lviv Dormition Brotherhood |

|

KYIV EPIPHANY BROTHERHOOD. A church brotherhood established ca 1615 at the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood Monastery in the Podil district of Kyiv by wealthy burghers, nobles, clergymen, and Cossacks to defend the Orthodox faith from the onslaught of Polish rule and Catholicism. Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny gave it a great deal of support and joined it 'with the entire Zaporozhian Host' in 1620. That same year the Orthodox Kyiv metropoly was restored and the brotherhood acquired stauropegion status and the right to establish a 'brotherhood for young men' from the visiting patriarch of Jerusalem, Theophanes III. The Polish king Sigismund III Vasa granted the brotherhood a royal charter in 1629. The brotherhood became a cultural and educational center in Kyiv. Many of Ukraine's leading figures were affiliated with it. To promote education, it founded the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School in 1615. Granted a charter by Theophanes in 1620 to teach 'Helleno-Slavonic and Latin-Polish letters,' in 1631 the school was merged with the Kyivan Cave Monastery School to form the Kyivan Mohyla College, which later became the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. Clerical involvement in the brotherhood forced its lay members--the burghers--into a secondary role. The brotherhood's 'elder brother,' Metropolitan Petro Mohyla, subordinated the brotherhood to the clergy in 1633, and the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood Monastery gradually took over its functions... |

| Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood |

|

LUTSK BROTHERHOOD OF THE ELEVATION OF THE CROSS. A renowned Orthodox brotherhood founded in 1617 in Lutsk by Herasym Mykulych, the hegumen of the Chernchytsi Monastery located near the city. The Lutsk Brotherhood included monks, priests, bishops, nobles, aristocrats, and members of the middle class from Lutsk and Volhynia. It received a charter from the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa in 1619 and was granted the status of stauropegion by the Patriarch of Constantinople in 1623. It ran the Lutsk Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Cross School and operated a printing press in the monastery. After Bohdan Khmelnytsky's era the brotherhood entered a period of steady decline. It was revived in 1896 by the Russian government with the intention that its activities 'strengthen the Russian people.' From 1920 the brotherhood functioned without a charter. In 1931 it was liquidated by the Polish government, only to be granted a new charter in 1935 which recognized the brotherhood's 17th-century roots but not the right to its holdings (they were left under government jurisdiction). The activities of the brotherhood ceased with the Soviet occupation of Lutsk... |

| Lutsk Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Cross |

|

KYIV EPIPHANY BROTHERHOOD SCHOOL. One of the most important Orthodox brotherhood schools in Ukraine. It was founded in 1615-16 by the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood, shortly after the brotherhood itself was organized. Modeled on the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School, its purpose was to diminish the enrollment of Orthodox children in Catholic schools. The school was open to boys from all estates. Its liberal arts program emphasized Church Slavonic and Greek. Its instructors came from Western Ukraine; they were graduates of the Ostroh Academy, the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School, and various Polish and German institutions of higher learning. The school's rectors were prominent Orthodox churchmen and scholars: Yov Boretsky (1615-18), Meletii Smotrytsky (1618-20), Kasiian Sakovych (1620-4), and Toma Yevlevych (1628-32). Among its graduates were a number of prominent scholars and cultural figures of the 17th century. The school greatly benefited from Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny's protection and the financial support of the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood. Patriarch Theophanes III of Jerusalem, who visited Kyiv in 1620, granted stauropegion to the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood and praised its educational work. In 1632 the school was merged with the school of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, which had been founded shortly before then by Archimandrite Petro Mohyla, to form the Kyivan Mohyla College (later the Kyivan Mohyla Academy), the most important educational institution in the Orthodox world of its time... |

| Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries dedicated to the brotherhoods and their influence on Ukrainian education and culture were made possible by the financial support of the SENIOR CITIZENS HOME OF TARAS H. SHEVCHENKO (WINDSOR) INC. FUND.

VI. THE ORIGINS AND TRADITION OF PRINTING IN UKRAINE

VI. THE ORIGINS AND TRADITION OF PRINTING IN UKRAINE

The invention of movable type and printing presses in Germany around 1450 had a tremendous and lasting influence on the cultural, social, religious, and scientific development of Europe. As the printing technologies spread throughout the continent and allowed for a quicker and wider dissemination of knowledge, they became a major catalyst for both the Reformation and the later scientific revolution. Printed books represented the key factor in the spread of education and literacy. In Ukraine, the first printing press was founded by Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) in Lviv in 1573. Its equipment and assets were used to found the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press (1591-1788), which played a key role in the history of early Ukrainian printing. Printing in Volhynia began after Fedorovych entered the service of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky and founded what became the important Ostroh Press (1577-1612). Founded in the early 17th century the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press became the most important center of printing and engraving in Ukraine until the mid 19th century; it played a crucial role in raising the level of education and culture and in aiding the Orthodox Ukrainians to defend themselves against the inroads of Polonization and Catholicism. An important printing press associated with the Uniate Church was established at the Pochaiv Monastery in 1730 after it became a centre of the Basilian monastic order... Learn more about the origins and traditions of book printing in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

|

PRINTING. The earliest books printed in the Ukrainian redaction of Church Slavonic and in the Cyrillic alphabet in general--the Orthodox Octoechos and Horologion--were produced in 1491 by Szwajpolt Fiol, a Franconian expatriate in Cracow. These were followed by liturgical books produced in the Lithuanian-Ruthenian state by short-lived presses on Belarusian territory, such as Frantsisk Skoryna's in Vilnius (1525), Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) and Piotr Mstislavets's in Zabludiv (now Zabludow, 1568-70), and Vasyl Tsiapinsky's itinerant press (ca 1565-70). The first printing press on Ukrainian territory was founded by Fedorovych in Lviv (1573-4). Thereafter Lviv remained a major printing center. In Kyiv, printing began with the founding of the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press (1615-1918). In 1787 a printing press was founded at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy; later it became the press of the Kyiv Theological Academy. In Left-Bank Ukraine the first printing presses were those of Kyrylo Stavrovetsky-Tranquillon in Chernihiv (1646) and Archbishop Lazar Baranovych in Novhorod-Siverskyi (1674-9), which was moved to Chernihiv and became the important Chernihiv Press. In 1720 Tsar Peter I subordinated the presses in Kyiv and Chernihiv to the Russian Orthodox church and forbade the printing of all but church books sanctioned by church censors in Saint Petersburg. From 1721 all books printed in Russian-ruled Ukraine were strictly controlled and censored, and all Ukrainianisms were consequently banned in imprints of liturgical texts... |

| Printing |

s monument_s.jpg)

|

FEDOROVYCH (FEDOROV), IVAN, b ca 1525, d 16 December 1583 in Lviv. Fedorovych was the founder of book printing and book publishing in Muscovy and Ukraine. He was deacon of Saint Nicholas Gostunsky Church in Moscow, where, from 1553, he oversaw the construction of a printing house commissioned by Tsar Ivan IV. This technical innovation created competition for the Muscovite scribes, who persecuted Fedorovych and finally caused him to flee to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Settling in Zabludow (Zabludiv) on the Ukrainian-Belarusian border, he changed his surname from Fedorov to Fedorovych. In Zabludow he published a Didactic Gospel, the so-called Zabludow Gospel (1569), and Psalter (1570). Fedorovych moved to Lviv in 1572 and resumed his work as a printer the following year at Lviv's Saint Onuphrius's Monastery. In 1575 Fedorovych, in the service of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, was placed in charge of the Derman Monastery; in 1577-9 he established the Ostroh Press, where, in 1581, he published the famous Ostroh Bible and some other books. He returned to Lviv after a quarrel with Prince Ostrozky, but his attempt to reopen his printing shop was unsuccessful. His printery became the property of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood. The brotherhood used Fedorovych's original designs until the early 19th century... |

| Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) |

|

OSTROH PRESS. The second oldest printing press in Ukraine, founded in 1578 by Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov) with the financial backing of Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky at the prince's castle in Ostroh, Volhynia. The Ostroh Press was closely affiliated with the Ostroh Academy, one of the first postsecondary institutions in Eastern Europe. At a time when Catholicism was making inroads into Western Ukraine, the academy was a bastion of Orthodoxy and maintained the traditional orientation toward Constantinople. Although it did not develop into a Western European-style university, as Ostrozky had hoped, it was the foremost Orthodox academy of its time. The first publications of the Ostroh Press were Azbuka (Alphabet, 1578), a collection of prayers in Greek and Church Slavonic; the second impression of Fedorovych's Bukvar (1578), the first Ukrainian primer; the first Ukrainian edition of the New Testament and an alphabetical index to it (1580); the famous Ostroh Bible (1581); and the first poetic work printed in Cyrillic, Andrii Rymsha's Khronolohiia (Chronology, 1581). The press also printed pro-Orthodox, anti-Uniate polemical literature, including works by Herasym Smotrytsky, Vasyl Surazky, Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, Khrystofor Filalet, and the pseudonymous Ostrozkyi Kliryk. The Ostroh Press functioned, with some interruptions, until 1612; from 1602 to 1605 it operated at the Derman Monastery... |

| Ostroh Press |

LVIV DORMITION BROTHERHOOD PRESS. A press founded in 1586 by the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood--the oldest and one of the leading Ukrainian brotherhoods, ie, laymen fraternities affiliated with individual churches in Ukraine that performed a number of religious and secular functions. The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood subsequently served as an example to other brotherhoods in Ukraine and Belarus. With a printing press and other equipment used by Ivan Fedorovych (Fedorov), the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press printed liturgical books, primers, poetry, dramas, and theological, educational, and polemical literature. Its oldest extant publications date from 1591: the 1589 charter of Patriarch Jeremiah II granting the brotherhood the right of stauropegion, a booklet of verses in honor of Metropolitan Mykhailo Rahoza, and the grammar Adelphotes. From 1591 to 1722 the press issued 140 books with a total run of some 160,000 copies. They were distributed throughout Polish-ruled Ukraine and Belarus, and even in Wallachia, Moldavia, Serbia, and Bulgaria. They were not, however, permitted to be sold in the Moscow-controlled Ukraine until 1707. The press played an important role in the intellectual life of Ukraine and the defense of the Orthodox church. In 1788 the Lviv brotherhood and its press were succeeded by the Stauropegion Institute... |

|

| Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press |

|

KYIVAN CAVE MONASTERY PRESS. The first imprimery in Kyiv and the most important center of printing and engraving in Ukraine in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was founded ca 1606-15 at the Kyivan Cave Monastery by the archimandrite Yelysei Pletenetsky, who purchased the equipment of the former Striatyn Press of Hedeon Balaban in Galicia. Later it was headed by, among others, Zakhariia Kopystensky, Petro Mohyla, Innokentii Gizel (for over 30 years), Varlaam Yasynsky, and Yoasaf Krokovsky. The imprimery issued several hundred titles on various subjects, both original works and translations, in Ukrainian, Church Slavonic, Polish, Russian, Latin, and Greek. The books printed included many ecclesiastical and liturgical texts, and also primers, hagiographic studies, Orthodox polemical treatises, didactic works, and literary works (panegyrics, emblems, epigrams). Beautifully engraved and ornamented, they were distributed throughout the Slavic countries, as well as Austria, Greece, and Moldavia. In the 16th and 17th centuries the imprimery played an important role in raising the level of education and culture in Ukraine. However, the tsarist ukase of 1720 limited it to printing only religious works that were strictly censored by the Holy Synod in Moscow, which it continued to do until 1918... |

| Kyivan Cave Monastery Press |

_s.jpg)

|

POCHAIV MONASTERY PRESS. An important early printing press in Ukraine, established at the Pochaiv Monastery in 1730 after it became a centre of the Basilian monastic order. Granted royal charters in 1732 and 1736, the press was subsidized by Bishop Teodosii Rudnytsky-Liubienitsky of Lutsk. Between 1731 and 1800 it published over 355 books, most of them liturgical ones, but also didactic gospels and theological books, works of polemical literature, literary works in Polish and Latin, collections of documents on Ukrainian church history, primers, textbooks, and educational works. Some of its editions were among the highest achievements of Ukrainian publishing and literature of the time. The press's publications were known for their artistic ornamentation and the quality of their paper and print. Many were printed in the so-called Pochaiv cursive, a typeface based on Ukrainian calligraphy of the 16th to 18th centuries. Illustrations and engravings were done by well-known artists, such as Nykodym Zubrytsky, Adam Hochemsky, Yosyf Hochemsky, and Teodor Strelbytsky. After the Pochaiv Monastery was taken over by the Russian Orthodox church in 1831, the press continued printing religious and secular books, including several on the history of Volhynia. The press was closed down in 1918... |

| Pochaiv Monastery Press |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the origins and traditions of book printing in Ukraine were made possible by the financial support of the FRANKO FAMILY FOUNDATION of Toronto, ON, Canada.

VII. THE CULTURAL LEGACY OF KYIVAN MOHYLA ACADEMY

VII. THE CULTURAL LEGACY OF KYIVAN MOHYLA ACADEMY

Established in 1632, Kyivan Mohyla Academy developed into the leading center of higher education in 17th- and 18th-century Ukraine, which exerted a significant intellectual influence over the entire Orthodox world. In founding the school, Metropolitan Petro Mohyla's purpose was to master the intellectual skills and learning of contemporary Europe and to apply them to the defense of the Orthodox faith. Taking his most dangerous adversary as the model, he adopted the organizational structure, the teaching methods, and the curriculum of the Jesuit schools. Unlike other Orthodox schools, which emphasized Church Slavonic and Greek, Mohyla's college gave primacy to Latin and Polish. This change was a victory for the more progressive churchmen, who appreciated the political and intellectual importance of these languages. From its beginnings, the academy had close ties with the Cossack starshyna, which provided it with moral and material support. The school, in turn, educated the succeeding generation of the service elite. Among the academy's students were the future hetmans Ivan Vyhovsky, Ivan Samoilovych, Pavlo Teteria, Ivan Mazepa, and Pavlo Polubotok. Many of the most accomplished Ukrainian intellectuals, authors, and churchmen of the time served on the school's faculty, and some of them played instrumental roles in Peter I's educational reforms. Among the academy's most famous students was the renown philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda. The academy was closed down by the tsarist authorities in 1817, and two years later the Kyiv Theological Academy was opened in its place. In 1991 Kyivan Mohyla Academy was formally revived as a national university and in 1992 it opened its doors to students on its historic campus... Learn more about the history and cultural legacy of Kyivan Mohyla Academy by visiting the following entries:

_s.jpg)

|

KYIVAN MOHYLA ACADEMY. Established by Petro Mohyla through the merger of the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School (est 1615-16) with the Kyivan Cave Monastery School (est 1631 by Mohyla), the new school was conceived by its founder as an academy, ie, an institution of higher learning offering philosophy and theology courses and supervising a network of secondary schools. Completing the Orthodox school system, it was to compete on an equal footing with Polish academies run by the Jesuits. Fearing such competition, King Wladyslaw IV Vasa granted the school the status of a mere college or secondary school, and prohibited it from teaching philosophy and theology. It was only in 1694 that Kyivan Mohyla College (Collegium Kijoviense Mohileanum) was granted the full privileges of an academy, and only in 1701 that it was recognized officially as an academy by Tsar Peter I. Supported generously by Hetman Samoilovych (1672-87), the school began to flourish towards the end of his rule, and during Hetman Ivan Mazepa's reign (1687-1709), enjoyed its golden age. The enrollment at the time exceeded 2,000. The Moscow academy was patterned after the Kyivan one and numerous Russian schools were organized by bishops who were graduates of the Kyiv academy... |

| Kyivan Mohyla Academy |

|

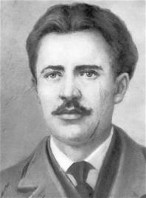

MOHYLA, PETRO, b 10 January 1597 in Moldavia, d 11 January 1647 in Kyiv. Ukrainian metropolitan, noble, and cultural figure; son of Simeon, hospodar of Wallachia (1601-2) and Moldavia (1606-7), and the Hungarian

princess Margareta. After his father's murder in 1607, Mohyla and his mother sought refuge in Western Ukraine. He was tutored by teachers of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School, and pursued

higher education in theology at the Zamostia Academy and in Netherlands and France. After his return to Ukraine he entered the military service and fought as an officer in the Battle of Cecora (1620) and Battle of Khotyn (1621). In 1621-7 he received estates in the Kyiv region and became interested in affairs of the Ukrainian Orthodox church. In 1627 he became archimandrite of the influential Kyivan Cave Monastery. In 1632 the Orthodox deputies in the Polish Sejm nominated Mohyla the metropolitan of Kyiv. He was consecrated on 7 May 1633. As metropolitan Mohyla improved the organizational structure of the Orthodox church in Ukraine, reformed the monastic orders, and enriched the theological canon. He gathered together a circle of scholars and cultural leaders known as the Mohyla Atheneum, which produced an impressive corpus of theological scholarship... |

| Mohyla, Petro |

|

PROKOPOVYCH, TEOFAN, b 18 June 1681 in Kyiv, d 19 September 1736 in Saint Petersburg. Orthodox archbishop, writer, scholar, and philosopher. He graduated from Kyivan Mohyla Academy in 1696 and continued his education in Lithuania, Poland, and in Rome. In 1704 he returned to the Mohyla Academy to teach poetics, rhetoric, philosophy, and theology. He also served as prefect from 1708 and rector in 1711-16. He gained prominence as a writer and as a supporter of Hetman Ivan Mazepa. His most famous work, Vladimir, is dedicated to the hetman, whom he depicted as the figure of the Grand Prince of Kyiv. Following Mazepa's unsuccessful revolt against Tsar Peter I in 1709, however, Prokopovych denounced him and expressed his complete allegiance to Peter. He became a favorite of Peter's and was called to Saint Petersburg to be a preacher and adviser to the tsar. He was consecrated bishop (1718) and then archbishop (1720) of Pskov, was appointed vice-president of the new Holy Synod in 1721, and finally was made archbishop of Novgorod in 1725. In the 1720s Prokopovych played a crucial role in the reform of the Russian Orthodox church. He supported the liquidation of the position of patriarch and the creation of the Holy Synod under the direct authority of the tsar... |

| Teofan Prokopovych |

|

YAVORSKY, STEFAN, b 1658 in Yavoriv, Galicia, d 27 November 1722 in Moscow. Orthodox hierarch, theologian, poet, and philosopher. A graduate of Kyivan Mohyla College (ca 1684), he completed his education in Polish Jesuit colleges. After returning to Kyiv in 1687, he renounced Catholicism, became an Orthodox monk (1689), and taught rhetoric (1690), philosophy (1691-3), and theology (1693-8) at Kyivan Mohyla Academy. He was hegumen of Saint Nicholas's Monastery in Kyiv from 1697; in 1700 he was appointed metropolitan of Riazan and Murom in Muscovy, and on 1 December 1701, exarch in Moscow of the Russian Orthodox church, by Tsar Peter I. Yavorsky helped Peter to reform the church and education. Eventually his defense of church autonomy, criticism of Peter, opposition to Teofan Prokopovych, and intolerance of Protestantism cost him the tsar's favor. In 1712 he was forbidden to preach, and in 1718 he was forced to live in Saint Petersburg and subjected to constant harassment and political inquiry. In 1721 Peter appointed him president of the Holy Synod, an institution Yavorsky abhorred. Yavorsky's major work is the anti-Protestant dogmatic treatise Kamen' very ... (The Faith's Rock ...), written 1718 and published 1728... |

| Stefan Yavorsky |

|

SKOVORODA, HRYHORII, b 3 December 1722 in Chornukhy, Lubny regiment, d 9 November 1794 in Pan-Ivanivka, Kharkiv vicegerency. Philosopher and poet. He was educated at Kyivan Mohyla Academy (1734-53, with two interruptions). He sang in Empress Elizabeth I's court Kapelle in Saint Petersburg (1741-4), served as music director at the Russian imperial mission in Tokai, Hungary (1745-50), and taught poetics at Pereiaslav College (1751). He resumed his studies at the Kyivan academy, but left after completing only two years of the four-year theology course. He later taught at Kharkiv College. After his dismissal from the college Skovoroda spent the rest of his life wandering about eastern Ukraine, particularly Slobidska Ukraine. Material support from friends enabled him to devote himself to reflection and writing. Although there is no sharp distinction between his literary and philosophical works, his collection of 30 verses titled The Garden of Divine Songs, his dozen or so songs, his 30 fables, and his letters, written mostly in Latin, are generally grouped under the former category. Some of his songs and poems became widely known and became part of Ukrainian folklore. His philosophical works consist of a treatise and 12 philosophical dialogues... |

| Hryhorii Skovoroda |

|

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF KYIV MOHYLA ACADEMY. A national coeducational research university in Kyiv. In 1991, by the ordinance of the head of the Supreme Council of Ukraine, the historical Kyivan Mohyla Academy was officially 'reestablished' on its 'historical territory as an independent institution of higher learning' under the name University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. The university was officially opened in August 1992, with literature specialist Viacheslav Briukhovetsky appointed as its 'organizing rector.' Briukhovetsky was the university's first elected president (acting from 1994 to 2007) and is generally considered to be the institution's 'founding father.' On 19 May 1994 by the decree of President Leonid Kravchuk, the university was granted the status of a national institution of higher learning and it assumed its present name. NaUKMA is a member of the European University Association. The teaching at the university is conducted both in Ukrainian and English. From its early days, the revived 'Kyivan Mohyla Academy' has firmly established itself as a leading university in Ukraine, patterned on North American academic models and generally considered the least corrupt of all classical universities in the country... |

| National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with the history and cultural legacy of Kyivan Mohyla Academy were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES.

VIII. UKRAINIAN MUSIC OF THE BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL PERIODS

VIII. UKRAINIAN MUSIC OF THE BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL PERIODS

The chief characteristics of Ukrainian religious music in the Middle Ages were a cappella singing and monophony. The melodies were recorded in a nonlinear notation, called znamenna, written in above the words of the liturgical services. In the 14th to 17th centuries the development of music in Ukraine was greatly influenced by church brotherhoods and their choirs. A significant innovation was the introduction of polyphonic singing, leading to the development of the five-line notation called kyivske znamia that replaced the non-linear notation. The 'musical grammar,' written by the musicologist and composer Mykola Dyletsky in 1675, was a complete description of the theory of polyphonic music. A favorite musical form of the time was the partesnyi concert, an a cappella composition for choir, consisting of one movement written to a religious text. The 18th century witnessed a paradoxical situation in which Ukrainian music started to reach a higher level of maturity and sophistication that was ultimately absorbed by Russian musical development. The Kyivan Mohyla Academy had an orchestra and choir comprising up to 100 musicians and 300 singers. The Hlukhiv Singing School provided thorough education for future musicians. But the musical talents of Ukraine usually did not remain in Ukraine; they were being drawn into the developing Russian musical life on an ever-increasing scale. The start of this trend could be seen already in the late 17th century, when Dyletsky was summoned to Moscow by the tsar to teach the rudiments of polyphonic singing, and in the early 18th century with the appointment of Ivan Popovsky as the precentor of the imperial court choir (and his subsequent recruitment of singers from Ukraine). From that time on, the most talented graduates of the Hlukhiv school were routinely brought to Saint Petersburg to further their musical education. The outcome of these practices can be seen by the late 18th century, when a trio of the most talented Ukrainian musicians of the age--Maksym Berezovsky, Dmytro Bortniansky, and Artem Vedel--composed exceptional works that became commonly regarded as 'Russian' music in the West... Learn more about the Ukrainian music of the Baroque and Classical periods by visiting the following entries:

CHURCH MUSIC. Religious music existed in Ukraine before the official adoption of Christianity, in the form of plainsong or musica practica. With the conversion to Christianity in 988, the Byzantine chant was imported together with Byzantine ritual. The distinguishing feature of Ukrainian church music was its exclusively vocal nature. An original Ukrainian church music first emerged in the 11th century at the Kyivan Cave Monastery, where the so-called Kyivan Cave Monastery chant was evolved. From the mid-16th to the end of the 17th century a contrapuntal or polyphonic singing (vocal music with simultaneous but melodically independent parts or voices) was developed in Ukraine. Polyphonic music was cultivated primarily by church brotherhood choirs. The choral concerto in one movement, composed for non-liturgical texts, became a very popular form. The composers of polyphonic music were, among others, Mykola Dyletsky and Andrii Rachynsky. Several outstanding Ukrainian composers of liturgical music, including Maksym Berezovsky, Artem Vedel, and Dmytro Bortniansky, emerged during the latter half of the 18th century... |

|

| Church music |

|

DYLETSKY, MYKOLA, b 1650? in Kyiv, d 1723? Music theoretician, composer, pedagogue. Dyletsky studied in Vilnius (1675) and worked for some time in Smolensk (1677), Kyiv, Moscow (1679), Saint Petersburg, Lviv, and Cracow. He was a master of polyphonic choral music. Among his works are compositions for four voices and eight voices, liturgical music, various motets, and canons. His most important theoretical work was Hramatyka muzykal'na (Musical Grammar), a textbook of polyphonic singing, which explains the fundamental theory of music, some principles of counterpoint, and the general rules of composition; it is illustrated by selections from the works of Dyletsky himself, M. Zamarevych, Ziuzka (probable pseudonym of either Lavrentii Zyzanii or Stepan Zyzanii), I. Koliada, M. Mylchevsky, Ye. Zakonnyk, and others. His theoretical views are augmented by comments on esthetics and on the educational value of music. The original text of the work, written in Vilnius in 1675, is not extant, but it exists in several variants and new redactions: 20 manuscript transcriptions are known... |

| Mykola Dyletsky |

|

BEREZOVSKY, MAKSYM, b 27 October 1745 in Hlukhiv, d 2 April 1777 in Saint Petersburg. A prominent composer, one of the creators of the Ukrainian choral style in sacred music. Berezovsky studied at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy and sang in the court choir in Saint Petersburg. From 1759 to 1760 he performed as soloist with the Italian opera company in Oranienbaum near Saint Petersburg. From 1765 to 1774 he studied in Bologna, Italy, under Giovanni Battista Martini, and in 1771 gained the title of maestro di musica and became a member of the Bologna Philharmonic Academy. In 1775 he returned to Saint Petersburg, where, as a result of court intrigues and difficult circumstances, he committed suicide. Berezovsky was the first representative of the early Classicist style in Ukrainian music. He was the composer of the opera Demofonte, a sonata for violin and harpsichord, and of a series of sacred works (including 12 concertos), of which only a few have been preserved. The recent discovery of his unknown Symphony No. 11 indicates that a considerable number of his other instrumental compositions must have been lost... |

| Maksym Berezovsky |

|

BORTNIANSKY, DMYTRO, b 1751 in Hlukhiv, d 10 October 1825 in Saint Petersburg. A prominent composer and conductor. After studying in the Hlukhiv Singing School, Bortniansky became a member of the court choir in Saint Petersburg in 1758. From 1769 to 1779 he studied in Italy, where he composed several operas to Italian librettos. Bortniansky also wrote liturgical works to Latin and German texts. On his return to Saint Petersburg he became a court composer, teacher, and conductor. During this period he composed his three French operas in 1786 and 1787. At the same time Bortniansky wrote a number of instrumental works (piano sonatas and a piano quintet with harp). In 1790 he wrote his Concerto-Symphony which for a long time (until the discovery of an earlier symphony by Maksym Berezovsky) was considered to be the first symphonic work composed in the Russian Empire. In 1796 he became the director of the court choir, which was composed mostly of Ukrainians and which he raised to a new level of excellence. During this period Bortniansky composed over 100 choral religious works... |

| Dmytro Bortniansky |

|

VEDEL, ARTEM, b 13 April 1767 in Kyiv, d 26 July 1808 in Kyiv. Composer, conductor, singer (tenor), violinist, and teacher. Educated at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, Vedel worked briefly as a choirmaster in Moscow. In 1792 he returned to Kyiv to conduct a military choir. The period 1792-7 saw the height of his musical creativity and he composed most of his choral concertos and other works at that time. In 1797 Tsar Paul I prohibited the performances in churches of choral concertos or any other forms except for liturgical music. This prohibition proved particularly harmful to musical culture in Ukraine where choral concertos were particularly popular. Left without work, Vedel briefly joined the Kyivan Cave Monastery. He was banished to a mental asylum in 1799 after church authorities attributed to him some irreverent marginal notes scribbled in a religious book. The incarceration ended Vedel's creative work and led to his premature death. The publication and performance of his works were banned for over one hundred years after his death. Oleksander Koshyts was one of the first choirmasters to include Vedel's works in his choir's repertoire...

|

| Artem Vedel |

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the Ukrainian music of the Baroque and Classical periods were made possible by the financial support of the STEPHEN AND OLGA PAWLUK UKRAINIAN STUDIES ENDOWMENT FUND at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (Edmonton, AB, Canada).

IX. THE TRADITION OF UKRAINIAN BOOK PUBLISHING

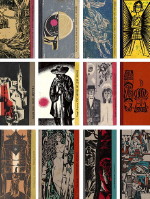

IX. THE TRADITION OF UKRAINIAN BOOK PUBLISHING

Books in manuscript form appeared in Ukraine with the coming of Christianity in the second half of the 10th century. By the end of the 11th century original books were produced in Kyivan Rus'. They were artistically transcribed in the monasteries, principally in Kyiv. However, the book production rapidly increased only after the invention of printing, although the industry still required manual labor, making large printings impossible for several centuries. The publishing of printed books was developed in Ukraine in the second half of the 16th century. The more noted publishers of the late 16th and the 17th centuries included Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky (the Ostroh Press; from the early 1580s), the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood (from 1586), Bishop Hedeon Balaban (the Striatyn Press), Mykhailo Slozka in Lviv, the Kyivan Cave Monastery (from 1617), Archbishop Lazar Baranovych in Novhorod-Siverskyi (from 1674), and others. Only at the beginning of the 19th century, when the manual press was replaced by the printing machine, did book printing become an important branch of industry. However, by the end of the 18th century, Ukrainian publishing houses declined because of bans imposed by the Russian government on printing Ukrainian books. The Valuev circular of 1863 and the Ems Ukase of 1876 made it virtually impossible for anything to be published in Ukrainian within the Russian Empire. Apart from individual exceptions, works by Ukrainian authors were published elsewhere, mostly in Austrian-ruled Lviv and by other emigre publishing houses, such as Mykhailo Drahomanov's Ukrainian Press in Geneva. In Austrian-ruled Galicia there were no government proscriptions to contend with. The first sporadic attempts at book publishing occurred in the 1830s. The Halytsko-Ruska Matytsia publishing house was established in 1848. The Prosvita society began to publish in 1877, and the Russophile Kachkovsky Society in 1874. The 1860s to 1880s saw the emergence of full-time periodicals, as well as of publishing houses of various political parties and educational organizations, such as the Ridna Skola society or the Shevchenko Scientific Society (NTSh)... Learn more about the tradition of Ukrainian book publishing by visiting the following entries:

|

BOOK PUBLISHING. The first book in the modern Ukrainian language--Ivan Kotliarevsky's Eneida (Aeneid)--was printed in Saint Petersburg in 1798, and the first Ukrainian publication printed in Ukraine--Petro Hulak-Artemovsky's Solopii ta Khivriia--appeared in Kharkiv in 1819. By 1847 the works of Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko, Mykola Kostomarov, Kotliarevsky, and others (about 100 works in all) had been published in Kharkiv. From then on, however, the tsarist government imposed various restrictions and bans on Ukrainian publications. As a result, the number of books published in Ukrainian hardly increased: it rose from 3 in 1848 to 41 in 1862, and then fell to 5 by 1865 and 1870 as the result of Petr Valuev's circular. In 1875 the number rose to 30, only to fall again to 2 in 1877 as a result of the Ems Ukase. In 1880 not one Ukrainian-language book was published in Russian-ruled Ukraine. Given such repressive conditions under Russia, from the 1860s Galicia, and particularly Lviv, became increasingly the center of Ukrainian book publishing. As early as 1875 more books were published in Galicia than in Russian-ruled Ukraine. In 1894, 177 books were published in Galicia (136 in Lviv), compared to 30 in eastern and central Ukraine. After the Revolution of 1905 conditions under Russia eased somewhat, and, in 1913, 246 Ukrainian-language books were published. That same year 326 books appeared in Galicia (238 in Lviv). Thus, until the outbreak of the First World War, Galicia led Ukraine in the production of Ukrainian books. In Bukovyna books from Galicia were read, although in the 1870s local publishers began to produce general educational literature and belles lettres in Ukrainian...

|

| Book publishing |

|