Yalta

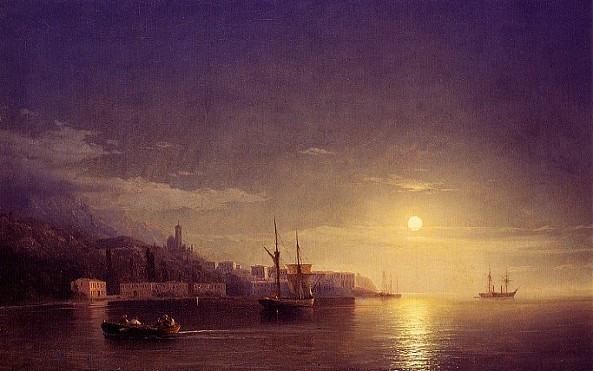

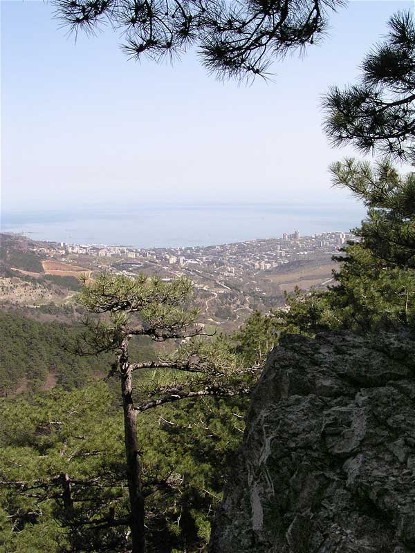

Yalta [Ялта; Jalta]. See Google Map; see EU map: IX-15. A city (2014 pop 78,200; 2021 pop 74,652), a resort of national importance and a port of call on the Crimean southern shore. Sheltered by the Crimean Mountains from the north, it lies on the subtropical coastal slopes overlooking Yalta Bay. It also serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality (aka Greater Yalta, 282.9 sq km, 2014 pop 142,137, of which urban pop 140,673 and rural pop 1,464 [2021 pop 137,947], containing the city of Alupka, pop 8,500 [9,063], 21 towns and 9 villages).

History. The earliest recorded reference to settlement on the site is to a Greek colony named Yalita (Halita) in the 1st century BC. Legend has it the name was derived from Greek sailors during a storm exclaiming (Γιαλός, yialos) meaning ‘a safe shore’ on which to land; more likely it is derived from the local Tavrian tribe called the ‘Yality.’ Control of the area later passed to Byzantium, and a fort was built there. By the 12th century the Cumans, who called it Dzhalita, retained it as a port and fishing village. Genoese traders had control of the town they would call Etalita in the 13th to 15th centuries until they were succeeded by the Turks in 1475. Destroyed by an earthquake in 1471, the town was rebuilt by Greek and Armenian residents who then called it, as the Turks did, Yalta. Following the Russo-Turkish wars and the Peace Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), the town was nearly depopulated because of the Imperial Russian government removing (1778–80) Christian Greeks and Armenians to the vicinity of present-day Mariupol, who established their town of Yalta there. Following Russian annexation of the Crimea in 1783, many of the remaining Crimean Tatars of Yalta emigrated to the Ottoman Empire; they were replaced by imperial Russian military: the Balaklava Greek Battalion, the quarantine servicemen, some fishermen, and merchants.

By the beginning of the 19th century the area around Yalta began to be colonized by estate owners. In 1823 Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, the governor-general of the New Russia, which included the Crimea, decided to cultivate Yalta as the major settlement on the Crimean southern shore. He had his palace built at Alupka (1828–48) and distributed land to the gentry and merchants who built palaces, villas, and mansions, laid out tobacco plantations, orchards, vineyards, and parks. The establishment of the Nikita Botanical Garden (1812) and its associated school of viticulture and wine-making provided expert guidance. By 1870, at the Magarach Winery laboratory, the well-known winemakers A. Serbulenko, A. Salomon, S. Okhremenko, and M. Khovrenko developed high-quality dessert wines. Yalta was chosen as the center because of its water supply and convenient bay. In 1838 the Yalta county (uezd) was formed (1,892 sq km, encompassing all of the Crimean southern shore and its mountains) and Yalta, with only 130 inhabitants (mostly fishermen), received the status of a city. The construction of a gravel road connecting Yalta with Alushta and Simferopol in 1837 and to Sevastopol in 1848 promoted the settlement’s growth. The building of a breakwater and a seaport enhanced Yalta’s position by the 1850s. During the Crimean War (1853–6) some Crimean Tatars were relocated to the Yalta county from the west coast of the Crimea to keep them from siding with the Turks.

Since the 1860s, Yalta began to expand as a resort and sanatorium center. Since its salubrious climate was praised by medical specialists (the tsar’s physician S. Bitkin and the local Ukrainian medical doctor Volodymyr Dmytriev), Yalta became a fashionable resort for the Russian aristocracy, gentry, and cultural elite. The Livadiia (1860s) and Masandra (1881–89) palaces were built for Tsar Alexander II and the ailing Tsar Alexander III (who died in the small Livadiia Palace in 1894). Private construction included the palaces of Prince Yusupov in Koreiz, Count D. Miliutin in Simeiz, Privy Councillor P. Gubonin in Hurzuf, Prince Golitsyn in Haspra and Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich in Nyzhnia Oreanda. Aristocrats of Ukrainian origin, from the Kochubei, Bezborodko, Danylevsky, and Alchevsky families, also built their mansions in Yalta. Even the emir of Bukhara had a palace built there (1907–11). The development of Yalta was enhanced by self-governance with the establishment of the county zemstvo based in the city (1866) and then of the city council chaired by its mayor (1871).

Ukrainian physicians contributed to the development of Yalta. The folklorist, poet and medical doctor, Stepan Rudansky, who served as the Yalta port and quarantine doctor (1861–73) as well as private physician of Prince Vorontsov, provided medical services to the needy pro bono, established a reception room for the sick and separate facilities for women, funded a city fountain and established the first medical library in Yalta. In his footsteps, the physician Volodymyr Dmytriev succeeded in persuading the authorities to build the city’s wastewater drainage (1886), water supply (1888), and the opening of the Yalta weather station.

The construction of the Yalta Embankment (1880s) and a stone breakwater and pier (1896, 1890) enhanced the city’s waterfront and port. The city’s cultural attributes were enriched by a theater (1896), 4 libraries, 4 cinematographs, and a newspaper (Yaltinskii listok, 1900–4). In 1904 a power plant and 4 small factories and by 1914 a tobacco factory, two lime plants, three mineral water plants and an ice-making plant were operating. Education was provided by 9 primary schools, two gymnasiums (est 1876), a school of commerce (courses in bookkeeping), a technical school (est 1880), and advanced courses in horticulture and viticulture. Its resort function expanded to include, by 1915, 5 charitable sanatoriums with 169 beds, a clinical children’s colony, an orphanage for 24 beds for tuberculosis patients, 3 private sanatoriums, 14 hotels with 800 rooms, and more than 5 boarding houses. In 1916, the Yalta Clinical Tuberculosis Institute was opened. Yalta attracted many seasonal and farm workers; 3,610 migrant workers were registered in 1900.

The city’s population, growing from 364 in 1861 to 1,100 in 1864, doubled from approximately 5,000 in 1885 to 10,000 by 1895. The 1897 census registered 13,155 Yalta residents, of whom (in percent) a minority (27.4) was locally born; a few (7.3) came from other parts of Tavriia gubernia, the majority (54.8) from other parts of the Russian Empire (many from Kursk gubernia, Orel gubernia, and Poltava gubernia) and some (10.5) from abroad. By contrast, of the 60,105 Yalta county residents, the overwhelming majority were locally born (74.8), with few from other parts of Tavriia gubernia (6.5), the Russian Empire (13.7) or abroad (5.0). In the city the predominantly Russian-speaking gentry, officials, merchants, skilled workers and domestics now outnumbered the indigenous Crimean Tatars, Greeks (who returned), Armenians, Karaites, and Krymchaks. The Ashkenazi Jews were allowed to settle in Yalta after 1860. This colonization, also apparent along the southern shore, hardly touched the outlying mountain villages inhabited by the Crimean Tatars. The religious-linguistic attributes of residents according to the 1897 census are summarized in Table 1.

By 1913 Yalta’s population exceeded 30,000. In 1914 the Yalta Municipality (encompassing Greater Yalta) was formed, which lasted until 1917.

Culturally, Yalta had an Imperial Russian façade with a significant Ukrainian component. It hosted Russian, Crimean Tatar, Polish and Ukrainian writers. Leo Tolstoy spent summers there; Anton Chekhov bought a house in Yalta, where he lived (1898–1902) and wrote plays. The Crimean Tatar reformer and newspaper editor, Ismail Kasprinsky, sometimes worked there. The Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz and Ukrainian writers Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, and Lesia Ukrainka visited the Crimea and stayed in Yalta. Like Mickiewicz, Ukrainka wrote about the Crimea and Yalta specifically. In her letters to her mother, Ukrainka remarked that local Ukrainians subscribed to Ukrainian publications and requested Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar for the city’s libraries. Visiting Ukrainian drama troupes, notably the Ukrainian theater troupe (est 1882 in Yelysavethrad), featuring actors Ivan Karpenko-Kary, Marko Kropyvnytsky, Mariia Azovska, Mykola Sadovsky, Mykhailo Starytsky, and Panas Saksahansky, were enthusiastically received by locals. In 1905 Yalta’s own Ukrainian drama group was formed.

During the Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent war Yalta changed hands 9 times. The main forces were: 1) the Crimean Tatar national movement, 2) the Russian moderate parties, 3) the Bolsheviks (Reds) who took the city from the sea (29 January to May 1918), terrorizing their perceived enemies (including Crimean Tatars), 4) the Germans, who with Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians expunged the Bolsheviks and 4) the Whites (led by Gen Anton Denikin and later Gen. Petr Wrangel).

Soviet rule. In 1920, following the defeat of Gen Petr Wrangel’s White Guardsmen, Yalta was the last city in the Crimea to be taken by the Red Army. The Bolsheviks carried out mass executions of surrendered White officers and soldiers, as well as all suspected opponents of the revolution. By 1921, the city’s population was reduced by some 8,000 residents to 22,671. That year, Yalta was renamed Krasnoarmeisk, but in 1922 its former name was returned. The imposition of War Communism, including collectivization or agriculture, led to the famine of 1921–3 in the Crimea, in which the Crimean Tatars in the Yalta county suffered the most. In 1923 Yalta became administrative center of its raion (one of six Crimean Tatar national raions). At this time, Crimean Tatars gained prerogatives in local policy and administration.

The 1926 census registered 28,838 residents in the city of Yalta and 35,965 in the Yalta okruha. The ethnic composition of the city (in percent) was predominantly Russian (56.5), with significant minorities of Crimean Tatars (10.9), Jews (8.8), Ukrainians (6.4), and Greeks (6.2). In the rural areas of the okruha (24,843), the ethnic composition (in percent) was overwhelmingly Crimean Tatar (80.7), with small Russian (12.8) and Ukrainian (3.5) minorities.

The Yalta Film Studio, established in 1922 with the local expertise of cinematographs, operated independently of Moscow until 1930. Although located in the Crimea, it became part of the All-Ukrainian Photo and Cinema Administration (1922–30). The studio employed famous actresses: the future Hollywood star Anna Sten (born Anna Fesak) and Varvara Masliuchenko. Scenarios were written by Ukrainian authors: Mykola Bazhan, Hryhorii Epik, Oles Dosvitny, and others. The first movie about the Crimean Tatar ‘Alim’ (directed by Georgii Tasin, scenario by Mykola Bazhan) was made here in 1926, but in 1937 it was banned by the Soviet government and all its copies destroyed. In the 1930s the houses of prayer were closed, farms collectivized, and the Crimean Tatar leadership purged.

The development of Yalta as a sanatorium center was planned soon after Vladimir Lenin signed (in 1920) the decree ‘On the Use of the Crimea for the Treatment of Working People.’ Palaces and mansions were nationalized and a master plan for the reconstruction of the Crimean southern shore was developed, but the devastation, poverty, and inadequate state of the budget of the USSR did not allow these plans to be implemented. Once the tsar’s estate in Livadiia became a sanatorium and the ‘Artek’ Pioneer Camp in Hurzuf was established in 1925, however, the construction of new health resorts began and continued through the 1930s. Yalta’s function as an all-Union resort was proclaimed by the city’s main newspaper name, Vsesoiuznaia zdravnitsa (1934–; since 1937 the newspaper has had other names). By 1939 the city’s population reached 32,683. In 1940 Yalta and its raion had 108 sanatoria and rest homes for 14,000 people, accommodating 120,000 in a year. Meanwhile, the cultural life of Crimean Tatars was altered by massive purges during the Yezhov terror of 1937–8.

The Second World War brought more population losses. Upon the evacuation of some Yalta residents and Communist Party activists, the motor ship ‘Armenia’ was sunk by a German aircraft (on 7 November 1941), resulting in the death of 5,000 to 7,000 people. German troops entered Yalta the same day, battled the partisans and Red Army raids (notably a group led by Anton Mitsko who temporarily raised the red flag over Yalta on 7 November 1943). Although German administration allowed for some cultural and religious activities, the Nazis fought organized resistance. Even so, Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian activists for independence revived cultural activities, such as the Ukrainian music and drama theater in Simferopol, which visited Yalta. During the German-Romanian occupation, the Nazis herded 4,500 Jews into a ghetto and then shot them in the Masandra area; altogether 11,707 citizens of Yalta were either killed of deported to forced labor as Ostarbeiter in Germany.

A month after the Soviet Army re-took the city (16 April 1944), all Crimean Tatars of the Yalta district were deported (18–20 May 1944, mostly to Uzbekistan); their settlement names were changed or erased. Other ‘suspect’ national minorities (Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks) were also removed. Russians (mostly from Belgorod oblast, Kursk oblast, Orel oblast, and Voronezh oblast) and some Ukrainians were re-settled in their place; German prisoners of war were used to re-build the infrastructure. The Crimea had its ‘autonomous’ designation removed to become the Crimean oblast within the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

By the end of the Second World War, the Yalta Conference (4–11 February 1945) was held at Livadiia Palace. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the guest-of-honor, was also housed there, Winston Churchill in the Vorontsov Palace, and Joseph Stalin in Yusupov Palace.

In 1948 the Yalta raion was eliminated and its constituent settlements (the city of Alupka, the towns of Haspra, Hurzuf, Koreiz, Livadiia, Masandra, Simeiz, and 7 villages) were subordinated to the Yalta city council as Greater Yalta.

In the Ukrainian SSR. To accelerate economic recovery and development, in 1954 the Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR. Economic development in the 1960s was marked by the expansion of water supply to include reservoirs on the north side of the Crimean Mountains (the Shchaslyve Water Reservoir and Yalta Hydro Tunnel, 1959–64). A new south shore bypass highway that connected Yalta through Alushta to Simferopol and west to Sevastopol; in 1961 the longest trolley bus line in Europe connected Yalta with Simferopol. Soviet elite and institutions had their resorts built in the area. Nikita Khrushchev had Dacha No. 1 on the coast at Oreanda, Leonid Brezhnev in Dubrava near Yalta, and Mikhail Gorbachev in Foros. The ‘Artek’ Pioneer Camp was developed (according to the plans of the architect Anatolii Poliansky; that included 150 buildings, 3 medical centers, a school, the film studio ‘ArtekFilm,’ 3 swimming pools, a stadium seating 7,000 and other sports facilities) to become an international youth center promoting Soviet propaganda. The city’s area expanded to incorporate three large villages. High-rise resort buildings were added in the 1970s and 1980s. By the end of the 1980s Greater Yalta had 180 sanatoriums or resorts accommodating annually nearly 2 million visitors.

With post-war reconstruction, by 1959 the city’s population grew to 44,000. Its ethnic make-up (in percent) was predominantly Russian (70), with growing Ukrainian (22), Belarusian (2), and renewed Jewish (2) and other minorities (4). Initially, the Ukrainian Soviet authorities encouraged some schooling and media in the Ukrainian language, but this was reversed in the 1970s. Meanwhile, the city’s population grew from 62,170 in 1970 to 80,098 in 1979, reached 89,000 in 1987 and then began to decline. By 1989 the Crimean Tatars started returning to the area, but had difficulty finding accommodation.

During the perestroika period, Ukrainian local activists worked to revive Ukrainian culture in Yalta and to establish a memorial museum of Lesia Ukrainka. Led by E. Proniuk of Kyiv, M. Okhrimenko (Yalta winemaker and former literary scholar), the bandurist Oleksii Nyrko, and many other Yalta supporters, their work resulted in a memorial plaque on the building where Lesia Ukrainka resided, a monument to the poetess in front of it (1972), and a collection of materials for the future museum. Anti-Ukrainian pressure, however, postponed the site’s designation as part of the Yalta Regional Studies Museum to the late 1980s. Restoration of the building was completed in 1990 and a exhibition ‘Lesia Ukrainka and the Crimea’ was opened there in 1991 on the 120th anniversary of her birth, providing the nucleus for the Lesia Ukrainka Memorial Museum. Outstanding among the Yalta Ukrainian activists was Oleksii Nyrko, a bandurist who had lived in the city since 1957. A professor of music at Yalta Pedagogical Institute, where he established a museum of the kobzar heritage of the Crimea and Kuban and a Kobzar Library in 1984, Nyrko later headed the Yalta Prosvita society (1988–91).

In independent Ukraine. Following the disintegration of the USSR, the city’s population peaked at 90,000 in 1992 and subsequently declined to 81,654 in 2001 and 78,032 in 2011. The ethnic make-up of Greater Yalta’s population of 139,554 in 2001 remained (in percent) predominantly Russian (65.5), with a growing Ukrainian minority (27.6) and Crimean Tatars (1.3) and Tatars (0.3), as well as Belarusians (1.6), Armenians (0.6), Jews (0.3), Azeris (0.3), Poles (0.2) and others (2.3). In the city itself there were fewer Crimean Tatars but a large Ukrainian minority; of the 81,654 residents in 2001, the ethnic composition was (in percent): Russians (67), Ukrainians (27), Belarusians (2), Crimean Tatars (1), others (3).

Ukrainian issues in Yalta were raised soon after the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence. In 1991 the ‘Lesia Ukrainka and the Crimea’ exhibition and revived and through the efforts of the Yalta branches of Prosvita and the Union of Ukrainian Women the Lesia Ukrainka Memorial Museum was established in 1993. In 1994 the congress of Ukrainians of South Crimea, held in Yalta, petitioned the Alushta and Yalta city councils to renew the use of Ukrainian as the language of instruction in schools, to raise Ukrainian national flags at government buildings, and to dismantle Soviet monuments. Most of these requests were not granted by the local authorities. By 2004 Yalta became the venue of an annual international ‘Yalta European Strategy’ (YES) Conference, funded by Victor Pinchuk, to promote the integration of Ukraine into the Europen Union.

In the early 1990s Yalta was affected by economic depression and re-structuring. The Communist Party lost monopoly on its property and the resorts of former Soviet elite were privatized. The ‘Artek’ complex was nationalized as part of Ukraine’s State Management of Affairs and re-named International Children’s Center (1991; by 1994 it began to cater to the needy children of Ukraine with the slogan ‘Our Land Is Ukraine’; about 90 percent of the attendees were Ukraine-born). At first, the newly-rich of the Russian Federation, with freedom and money to travel, turned to other European holiday resorts; meanwhile, the impoverished ex-Soviet citizens could no longer afford to go to Yalta. As a result the tourist industry in the city stagnated. As the economy of Ukraine recovered, the city authorities, under the leadership of the mayors Serhii Braiko (2002–6, 2006–10) and Oleksii Boiarchuk (2010–12) (both members of the Party of Regions), made improvements to Yalta’s beachfront infrastructure (2003) and other facilities, which brought a revival to tourism. Most visitors came to Yalta from Ukraine and the Russian Federation; Westerners (12 percent in 2013 from some 200 cruise ships) were a minority.

With the Russian annexation of the Crimea, Yalta lost its Ukrainian institutions and private properties. Residents were required to become Russian citizens, as all services were denied to those without Russian passports. Ukrainian instruction in schools was forbidden and the Lesia Ukrainka Memorial Museum was closed. Ukrainian and Western tourists stayed away, but Russian visitors made up some of the difference. Yalta’s population diminished from 78,115 in 2013 to 76,746 in 2014, and then fluctuated since, down to 74,652 in 2021.

Economy. Yalta is the leading resort in the Crimea and Ukraine in general. Nestled in a scenic location between the Black Sea and the Crimean Mountains, it is particularly noted for its Mediterranean climate. The city and its surrounding environs had, in 1975, 65 sanatoriums, 18 health resorts, and 8 boarding hotels with a summer capacity of approximately 39,000 beds. By 2012 the facilities expanded to 144 entities, including 70 sanatoriums, 17 boarding houses, 16 rest homes, 18 rest camps, 8 health camps (including the ‘Artek’ children health camp at Hurzuf), 4 tourist bases and 11 hotels (including the ‘Yalta-intourist’, ‘Oreanda’ complexes). That year Greater Yalta hosted some 2 million visitors in one season, about one-third of all the visitors to the Crimea. In 2013 a 5-star Hilton was built in place of the ‘Sevastopol’ sanatorium, but with the Russian annexation and international sanctions (2014), its ownership changed.

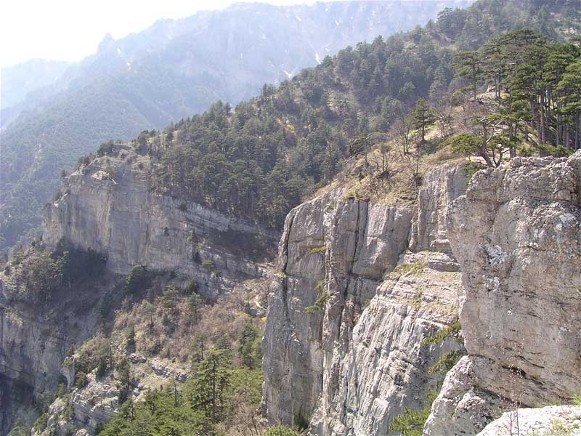

Natural attractions of Greater Yalta are its beaches and mountains. The pebble beaches (59 km along the coast), protected with structures against erosion, provide clear water for bathing (the prestigious international Blue Flag awarded to Yalta’s Masandra Beach in 2010). The Yalta Mountain and Forest Nature Reserve, extending the length of Greater Yalta along the Crimean Mountains ridge and slopes, has endemic fauna and flora and offers hikers panoramic views from high vantage points; cultivated plants are studied and displayed at the Nikita Botanical Garden.

Supporting tourism is the food industry (representing 95 percent of Greater Yalta’s industry by value of production); the main branches are winemaking (42 percent) and fisheries (19 percent); other branches of food processing include baking, meat processing, and the production of nonalcoholic beverages. In Greater Yalta the ‘Masandra’ National enterprise with its Livadiia and Hurzuf plants and its main Masandra plant specialize in the processing of quality grape varieties: Muscat (white, red, rose), Cabernet, Tokaj, Albillo, Saperavi, Pinot and others. Fish are processed at the ‘Promin’ plant. Winemaking is supported by the ‘Maharach’ Scientific-Research Institute of Grape-growing and Winemaking and the ‘Masandra’ winery.

Commerce is facilitated with transport and communication facilities, wholesale and retail outlets, banks and other services. Two major enterprises serve the construction industry, and one each for water supply and energy procurement.

Resort management and development is supported by its Resort Scientific Research Institute, the Yalta Branch of the Crimean Scientific Research Institute of Project Planning, and the Yalta Branch of the Crimean Resort Project Planning. Sanatoria, specializing in therapy for tuberculosis (mostly in Yalta) and other ailments (respiratory, blood circulation, nervous system) in Greater Yalta, are supported with medical research at the Institute of Physical Methods of Therapy and the I. Sechenov Institute of Medical Climatology.

Other research facilities located in Greater Yalta include 1) the Black Sea Division of the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (originally, the Black Sea Hydrophysical Station [est 1929 at Katsiveli village], on the basis of which the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of Academy of Sciences of the USSR [Moscow] was created in 1948; the station became part of the Academy of Sciences of Ukrainian SSR in 1961; in 1963 the Institute was relocated to its new facilities in Sevastopol and became the Marine Hydrophysical Institute of Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, but the station at Katsiveli continued its work; in 2015 this institute at both locations was taken over by the Russian Academy of Sciences); 2) the Yalta Marine Hydrometeorological Station; 3) Hydrochemical Laboratory for Crimean Basin Management, Use and Conservation of Water; 4) Radio Telescope (RT-22) of the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory (est 1966 at Simeiz, operated by the Radio Astronomy Laboratory of Crimean Astrophysical Observatory of the Ministry of Education and Sciences of Ukraine in 2012) and 4) Seismic Station Yalta.

Culture. The modern growth of Yalta left a prevalent veneer of upper class imperial Russian and then Soviet and post-Soviet culture, with hints of Greek, Crimean Tatar, or other cultures that preceded or coexisted in the area. Even when the Crimea was part of independent Ukraine, Ukrainian attributes increased only marginally.

The education system of the Soviet period developed in the Russian language with an emphasis on technical training. It was slightly modified after the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence. Of the 26 schools in Greater Yalta (with 16,540 pupils), only one (School No. 15) provided instruction in the Ukrainian language (1994–2014). The elite experimental innovative high school No. 2 (est 1971, equipped with internet and re-named in 2007 ‘School of the Future,’ supported by an eponymous charitable organization, based in Kyiv), also offered courses in Ukrainian literature.

At the level of postsecondary institutions in the Soviet period there were one trade school, one medical school, one pedagogical institute, and three technical schools; with Ukraine’s independence the institutions diversified to include humanities and private schools. These included: 1) the Crimean Republic’s Yalta Higher Professional School of Building and Food Technologies), 2) the Crimean Republic’s Humanitarian University (formerly the Yalta Teachers School, est 1944, became college [1994], then university [2005], with branches in Yevpatoriia and Armiansk), 3) a private Yalta University of Management, 4) the Yalta commercial technical branch of the National University of Food Technologies (Kyiv; est 1884 in Smila, moved to Kyiv in 1930), and 5) a medical college. Greater Yalta has a centralized library system (est 1976) with its main Anton Chekhov Central City Library and 10 branches (2010).

Sports, important in Soviet education, were modernized in the post-Soviet period. By 2010 the city had 35 sports organizations featuring 21 kinds of sport, of which 12 pertained to Olympic competitions. Famous Yalta athletes include L. Osmanova (powerlifting), A. Vedenmeyer (rock climbing), A. Risnyk (kickboxing), Yu. Sokolov (Muay Thai or Thai boxing), and R. Zahorodniuk (boxing). Yalta has its football stadium (Stadion Avangard Yalta, home of the professional FC Zhemchuzhyna Yalta (2010–14); since Russian annexation, it became home of FC Rubin Yalta (promoted from an amateur club established in 2009, supplemented with professional players from the disbanded FC Zhemchuzhyna Yalta, playing in the Crimean Premier League and, since 2023, in the Russian Second League Division), an Olympic swimming pool among others, 35 sports clubs representing 21 different kinds, including 12 Olympic sports.

As an international resort, Yalta used to spring to life in summer-time with theater and movie festivals. When it was part of independent Ukraine, this included the International Folklore Festival (from 1999), International Telefilm Forum ‘Razom’ (from 2000), Classical Music Festival ‘Zirky planety,’ and many others. The city then also thrived with 285 different social organizations, including 17 regional branches of political parties, and creative people of all stripes. Cultural venues included the ‘Jubilee’ Concert Hall (seating 2,600, originally a venue built in the 1880s, re-built in 1973 and re-constructed in 1988), the Anton Chekhov Theater (originally built in 1883 seating 315, destroyed by fire [1900], re-built [1908] to seat 700, saved from fire and re-named after Anton Chekhov [1944], closed [1996], restored [2007–8]), the Yalta Culture Center (with a music and movie theater) and the Livadiia Center of Organ Music (in the former power house for the Livadiia Palace, featuring the largest organ in the former Soviet Union, constructed in 1998 and enhanced later by the Yalta organist, Volodymyr Khromchenko). There are several small fine art galleries.

Tourist attractions include Yalta’s seaside promenade (restored in 2003–4) and old luxury hotels (the Bristol Hotel [built 1860s as Yalta Hotel, rebuilt 1906 and re-named Bristol Hotel]; the Tavrida Hotel [built 1875 as the more luxurious Rosiia Hotel, 150 rooms]; the Roffe Baths [built in 1897 in Moorish style, used as base for ‘Chervona Ruta’ tour in 1975, saved from demolition in 1984 by Sofiia Rotaru, restored in 1991, bought by Sofiia Rotaru and made into boutique hotel ‘Villa Sofia’ [2008]; the Lishchynsky tenement [built 1884–5 by architect P. Terebenev, in the Moorish style, contains the Lesia Ukrainka Museum]), and the Crimean film studio ‘Yaltafilm.’ The city has 2,575 ha of parks and gardens.

Notable architectural monuments near the city are 1) the Livadiia Grand Palace Museum complex (built 1910–11 of white Crimean limestone in Neo-Renaissance style, architect M. Krasnov, replacing a smaller palace built in the 1860s, architect Ippolito Monighetti, for the Russian imperial family), 2) the Vorontsov Palace Museum complex in Alupka (built between 1828 and 1848 [for the Russian Prince Mikhail Vorontsov in a loose interpretation of the English Renaissance revival style, with elements of Scottish Baronial, Indo-Saracen revival architecture, and Gothic revival architecture, by English architect Edward Blore and his assistant William Hunt] within a 40 ha park ensemble [arranged by German landscape gardener Carolus Keebach]); less grandiose are 3) the associated Masandra Palace (a Châteauesque villa commissioned by Semen Vorontsov for Emperor Alexander III of Russia in Masandra, built 1881, 1892–1900 in Gothic revival style by the architect Maximilian Messmacher), 4) the spectacular Swallow’s Nest castle in Miskhor (built between 1911 and 1912, on top of the 40-metre-high Aurora Cliff overlooking the Black Sea, in a Neo-Gothic design by the Russian architect Leonid Sherwood for a Russian noble with German roots, Pavel von Steingel), 5) the Dulber Palace in Koreiz (built 1895–7 in Moorish revival style, architect Nikolai Krasnov, for Grand Duke Petr Romanov; now a sanatorium), 6) the Gaspra Palace in Koreiz (built 1831–6 in Gothic English castle style, architect William Hunt, for Prince Aleksandr Golitsyn [1843–4], now a sanatorium); and in Yalta 7) the Emir of Bukhara Palace (built 1907–11 for Syed Abdul Ahad Khan [the ninth Emir of Bukhara] by architect N. Tarasov, using elements of Muslim architecture of North Africa; now a sanatorium), 8) the Countess M. Vadarsky Chateau (built 1902–9, architect E. Steffer, in Moorish architecture style, now a sanatorium), and 9) home of the composer Aleksandr Spendiarov (built 1891–5 by architect G. Sсhreiber in Neo-Grec style, enlarged and embellished in 1900 by architect Nikolai Krasnov with caryatids supporting 3rd floor balcony roof with two griffins; the building was damaged in the 1927 earthquake and in the Second World War, was re-built, used as a travel bureau in the 1980s).

Belonging to this period are 4 notable Russian Orthodox churches, restored while in post-Soviet independent Ukraine. In the city they are: 1) the Saint John Chrysostom Church (commissioned by governor-general Mikhail Vorontsov, designed by Giorgio Torricelli and bult in 1832–7 [5-dome] as the first cathedral of Yalta; enlarged and modified in the 1880s by the architect Nikolai Krasnov [single-dome]; destroyed in 1942; re-built in 1994–8 based on the Torricelli design); 2) the Aleksandr Nevsky Cathedral (built 1891–1902 as the city’s new cathedral in memory of Tsar Alexander II by architects N. Krasnov and P. Terebenev, in ornate old Muscovy style, with separate 3-story building for school, meetings of brotherhood; closed by the Soviets in 1938 and converted into sports club; re-opened for service during German occupation, remained in service thereafter). Beyond the city are: 3) in Oreanda, the Protectress Holy Mother of God (commissioned by Prince Konstantin Romanov, built 1884–5 in Georgian-Byzantine style, architect Aleksei Avdeev, mosaics by Antonio Salviati, closed for worship in 1924, damaged by earthquake in 1927, converted to workshop, then fruit storage; its mosaics and icons did not survive; returned to the faithful in 1992, opened for service and restoration; belfry added in 2001); 4) in Foros, the Resurrection of Christ Church (built on a cliff [400 m above sea level] overlooking Foros in 1888–92, architect N. Chagin; closed by the Soviets in 1924, its valuables removed in 1927; became a restaurant in 1934; restoration began in 1987 by the Sevastopol branch of ‘Ukrrestavratsiia’ and transferred to the Russian Orthodox church in 1990; upon request of President Leonid Kuchma, included in the list of important churches of Ukraine and its restoration completed in 2004). Also from this period are 1) the Greek Church of the Holy Martyr Theodore Tiron (on site of earlier church that was there before the removal of Greeks to Mariupol; a wooden church was erected after their return in 1842; replaced by a stone church in Byzantine style in 1898; now part of the Russian Orthodox church); 2) the Armenian Surb Ripsime Church (built 1909–17, architect Gavriil Ter-Mikelov, used as site for film-making [1927–73]; since 1960 used by Yalta Regional Studies Museum; on 100th anniversary held Armenian Apostolic Church service in 2010); 3) the Saint Mary Lutheran Church (built 1885) and 4) the Roman Catholic Church of Immaculate Conception (built 1898–1906, architect Nikolai Krasnov, in neo-Gothic style; closed after the 1927 earthquake; in 1930s used as a shooting gallery, then a gym; after 1945, part of the regional studies museum; in 1988 the organ was restored and in 1989 became a house of organ music, restored by the architect Oleh Hrauzhys; opened to religious service in 1991; since 1993 it was shared with the Ukrainian Catholic church).

In the post-Soviet period after 1991 more Russian Orthodox churches (re-named, when part of Ukraine, belonging to Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate) were built. Outstanding among the former is Saint Michael the Archangel Church in Oreanda (in Cossack baroque style with outstanding acoustics, built 2005–6, architect Viacheslav Bondarenko, iconographers from western Ukraine led by V. Humeniuk). Other houses of worship included the Evangelical ‘Znamia Khrysta’ and the Jehovah’s Witnesses ‘Zal Tsarstva’. With the return of the Crimean Tatars the Medrese Mosque (Mechet Medrese, where Ismail Kasprinsky once worked) and three small mosques, the Orta Jami in the northern suburb of Yalta, the Koreiz Mosque (in Koreiz) and Juma Jami in Simeiz were built.

Establishing churches for Ukrainian speakers was more difficult. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate was never permitted to get land to build a church in Greater Yalta. The Ukrainian Catholic church also encountered obstructions for a separate church, until Petro Tokachiv sponsored its construction on his own property in Vidradne (a town on the east side of Yalta): the Holy Trinity Church (built in 2011 in 10 months [resembling a miniature copy of Saint Sophia in Rome], containing the relics of Saint Clement I [Pope of Rome, 99 AD, and martyr]).

Sites from antiquity near Yalta include what were medieval fortifications on the Biyuk-Istar (Big Fortress) Peak (732 m above sea level, 4 km WNW of Simeiz) and a Byzantine cave church (from 9–10th centuries until beginning of 20th century, then destroyed) at the Iograf Ridge (1250 m above sea level, 5 km NW of Yalta city center).

Major museums in Yalta are: 1) the Yalta Historical and Literary Museum (est 1891 at the Crimean Mountain Club; in 1918, at a new location, re-named Yalta Natural-Historical Museum; in 1924 re-named Regional Studies Museum; in 1932 combined with the Eastern Museum; during the Second World War evacuated to Novosibirsk; in 1957 expanded to include the K. Trenev and P. Pavlenko Literary Memorial Museum; in 1970 opened a branch at the former M. Biriukov estate and established an outdoor branch, the ‘Glade of Tales’; in 1985 the museum was re-named historical and temporarily incorporated the Aleksandr Pushkin Museum (at Hurzuf) which, by 1999 again became a separate entity; in 1990 re-named ‘Yalta State Unified Historical-Literary Museum; in 2003 attained its current name). 2) the Aleksandr Pushkin Museum at Hurzuf (est. 1938 in a house built in 1911 and owned by the governor-general of New Russia and Bessarabia Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis duc de Richelieu, where Aleksandr Pushkin stayed in 1820). 3) the Anton Chekhov House Museum (where Anton Chekhov lived, for health reasons, the last 6 years of his life and wrote 2 plays, 4 stories, and a novel; he bought the property [1898] and had his house built [1899]).

Of particular importance to Ukrainians is the Lesia Ukrainka Memorial Museum (in the Lishchynsky building [built 1884–5], where Lesia Ukrainka lived for 2 years). On 10 September 1993, after demands by the Yalta Prosvita, the Association of Ukrainian Women, and other local Ukrainians, the resistance of the city administrators was overcome and the place was granted the status of the ‘Lesia Ukrainka Museum’ as branch of the Yalta Historical and Literary Museum. With the financial assistance of the international fund ‘Vidrodzhennia,’ the museum was extensively renovated and its holdings expanded in preparation for the celebration of the poetess’ 130th anniversary. The museum became a nucleus of Ukrainian cultural life: a Sunday School of Ukrainian Studies (1994, its principal, Svitlana Kocherha, also curator of the museum), the gathering place for Prosvita, the Association of Ukrainian Women, and ‘Kryms’ka kutia’ club of Ukrainian creative intelligentsia. The Sunday school’s students formed an amateur ‘Seven Muses’ amateur theater group that staged many plays, including Lesia Ukrainka’s Stone Host. The museum also hosted visiting exhibitions of famous Ukrainian writers and an exhibit of Oleksii Nyrko’s Crimean and Kuban bandura collection. After the Russian occupation (2014) the museum was closed.

Memorials in Yalta from the Soviet period include the ‘Hill of Glory’ (1967), and the statues of Anton Chekhov [1953], Vladimir Lenin [1954], and Maxim Gorky [1956]). Also located in the city are a statue of Lesia Ukrainka (bronze, architect A. Ihnashchenko, sculptress Halyna Kalchenko, 1972) and the grave of Stepan Rudansky (featuring a stone monument with a bronze high-relief of his face and his verse on it, 1968). Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, other monuments were added, including to the ‘Victims of Deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944’ (through the efforts of the Mejlis, 1994), to ‘Soldiers-Internationalists who died in Afghanistan’ (2013), and some statues of Russian writers (Anton Chekhov and Lady with her dog [2004], Aleksandr Pushkin [2010], Yu. Semenov [2012]), the entrepreneur and film-maker A. Khanzhonkov (2011), and with the support of Ukrainian diaspora, the Ukrainian Bard, Taras Shevchenko (bronze, architect and sculptor Leonid Molodozhanyn, molded in Argentina, unveiled in 2007). After 2014 the Yalta Conference was noted with a statue of the ‘Big Three’ (Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, unveiled in 2015 at Livadiia), and Alexander III (2017 at Livadiia).

City plan. Greater Yalta occupies an elongated area of about 282.9 sq km from the ridge of the Crimean Mountains to the Crimean southern shore. It extends along the Black Sea coast about 56 km and reaches inland 7 km at Yalta. The higher elevations (300 to 1,000+ m above sea level) consist of the Yalta Mountain and Forest Nature Reserve (146 sq km), although in the west the reserve reaches lower elevations and approaches the coast in 5 locations. It also has a coastal outlier near the town of Nikita in the east, the Mys Martian Nature Reserve. From WSW to ENE, the lower elevations along the coast host a chain of settlements, comprising towns (2014 pop) and villages: Foros (1,996), Sanatorne (490), Olyva, Berehove (489), Parkove (500), Opolzneve, Ponyzivka (384), Katsiveli (625), Holuba Zatoka (443), Symeiz (3,919), the city of Alupka (8,528), Koreiz (6,337), Haspra (11,384), Kurpaty (415), Oreanda (921), Hirne; Livadiia (1,636) and Vynohradne (1,406) on the western border of Yalta, the city of Yalta (78,200); NNW of it, Kuibysheve, NNE of it Sovietske (579) and E of it Masandra (8,623) and Vidradne; and then Voskhod (456), Nikita (2,473), Danylivka, Partyzanske, Hurzuf (9,152) and Krasnokamianka (1,021). The settlements are interconnected by winding roads. Traffic is expedited with the bypass South Shore Highway: from the city of Yalta eastward (E-105) via Alushta and north to Simferopol, and westward (H-19) from the city of Yalta towards Sevastopol. A tortuous roadway (T0117) from the city of Yalta via Vynohradne crosses the Ai-Petri Ridge WNW to Bakhchesarai. Between the settlements the area is mostly wooded, with some orchards and vineyards both near and east of the city of Yalta.

The city of Yalta occupies a hilly amphitheater facing Yalta Bay forming an irregular rectangle extending about 5.5 km from SW to NE, about 3 km from NW to the coast in the SE, and covers an area of about 15 sq km. Through Yalta flow two small rivers: from the west the Uchan-Su (in the city canalized and called ‘Vodospadna’); from the north, the Bola, merging with Huva from the east to become Derekoika (canalized in the city where it is called ‘Shvydka’; it is covered at its mouth near the old Yalta port).

In the 19th century Yalta began as a settlement near the mouth of the Derekoika River, with a market on its east bank, its port in the cove formed by the foreland Cape John to the east, where on higher ground some residences and the Saint John Chrysostom Church (1832–7) were built. A twisting road led NW to Masandra, Nikita, and points east. As Yalta developed into a resort it expanded SW along the bay’s shore with an embankment, called Aleksandrovskaia Naberezhnaia, behind which shops, hotels, tenements and cultural venues were built. By the 20th century it reached SW to the mouth of the Uchan-Su where it absorbed, upstream, the village of Autka, and across the river mouth, along Nicholas Street, towards Livadiia. From the port it spread N, up the Derekoika River to the villages of Derekoi and Ai-Vassil (Vasylivka), grew north between the two rivers, west across Uchan-Su to merge with Livadiiskaia Sloboda, and northeast to Masandra.

Presently, Yalta’s city center may be defined by its main thoroughfares: 1) in the SE, the re-named Lenin Embankment on the Black Sea coast; 2) in the east, a set of one-way thoroughfares flanking the canalized Derekoika River: Kyiv Street (on its west bank, with traffic south, towards the embankment and the port) and Moscow Street (on the east bank, north, towards the South Shore Highway and points east); 3) in the west, flanking the Uchan-Su (Vodospadna), the Pushkin and Gogol streets; and 4) between the two rivers, north of the embankment, an E-W artery, comprising a chain of streets: Karl Marx, Sadova, Kirov, and Marshaka.

At the cove, protected by breakwater from the south, is Yalta’s passenger port. Behind it stands the old Bristol Hotel, on the park-like Roosevelt Street that follows the shore around the foreland, marked by the Saint Nicholas Tower (1896). Inland from the port, to the NE, lead two streets, Rudansky and Sverdlov, flanked by mostly old multi-story buildings with institutional, residential and commercial uses, and the park-like Rudansky Square. East of it, on Tolstoy Street in a park-like setting, is the Saint John Chrysostom Church. Beyond it to the east is old residential housing.

The embankment, at its NE end, has an open plaza. On its N side is Lenin Square, offset by greenery and flanked by services, with the main post office on its west side and the old Krym Hotel on the east side. The embankment comprises of a broad promenade, partly lined with trees, with access to the docks and farther west to the beach on the SE side and shops and restaurants on the NW side. At its SW end is the Kalinin Square with a monument commemorating the 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars. On Yekaterininska Street facing the Kalinin Square is the house of the composer A. Spendiarov (NE side), and beyond it, the Lesia Ukrainka Memorial Museum and the Anton Chekhov Theater.

In the west, the Uchan-Su (Vodospadna) is flanked by Pushkin Street on its N bank, where the Yalta Historical and Literary Museum is located, and Gogol Street on the south bank, with School No. 10 (where German language is taught) and behind it, on Zarichna Street, where the Yalta Branch of the V. Vernadsky Humanitarian-Pedagogical Academy (formerly, the Crimean Humanitarian University) is located.

The central east-west arterial has important institutions and sites of interest. In the east, the Karl Marx Street forms the city’s main intersection with Kyiv and Moscow streets. Here, on the N side of Karl Marx Street at Kyiv Street is the Yalta city hall; E of it is the city market; N of the city hall is the Soviet Square with a pool and fountain and on its west side a large shopping mall. To the west, Karl Marx Street merges with and becomes Sadova Street where, on the S side, are the Nekrasov Square park, and next to it, the Tavrida Hotel; farther west, on the N side of Sadova is the Aleksandr Nevsky Cathedral. On the S side of Kirov Street is the Yalta office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, west of it the headquarters of the Yalta Investigation Committee, then the Prosecutor’s Office, and on the N side the Yalta City Courthouse. Farther west, beyond some opulent houses, including the mansions of the merchant Hofsneider (1880s) and dacha ‘Omiur’ (1888) on the S side, is the ‘Maharach’ Scientific Research Institute of Grape-growing and Winemaking. From here, Marshak Street leads to Uchan-Su (Vodospadna), the western periphery of downtown Yalta.

The peripheral parts of the city are described by sectors outward from the center, in a clockwise order. Along the coast, SW of the mouth of Uchan Su, the Lenin Embankment becomes the winding Communars Street. It passes through an area of some post-war or newly built sanatoria near beaches, notably the Oreanda Complex, but also inland past the Bukhara Emir Palace to the wooded Chukurlar Park and inland the Water Park Hotel Atlantis, both of which border on Livadiia. On streets inland to the NW there is a mix of apartments and small hotels to accommodate visitors and the small Resurrection of Christ Orthodox Church.

As Communars Street enters Livadiia, it passes a built-up area of apartments and police station (NW side) and vineyards (SE side) and joins the Sevastopol Highway, which follows the western outskirts of the old town comprising single-family housing. At its entrance, on Baturyn Street, is School No. 14; then the street leads south, past the Center of Organ Music, towards the Livadiia Palace complex. On the west side of the Sevastopol Highway is Yalta City Hospital No. 1, specializing in pulmonology.

The segment inland and SW of the ‘Avangard Yalta’ Stadium has School No. 2 (the prestigious School of the Future) and is mostly residential, with old individual houses. Farther SW, toward the Sevastopol Highway, are several neighborhoods of multi-story apartment buildings. West of the ‘Avangard Yalta’ Stadium, along the winding Bliukher Street is a cluster of multi-story apartments, a small market and near the river a Baptist Church; SSW of this cluster is a medical center and a helicopter pad. North of the helicopter pad, near the bypass highway, is Yalta’s Lower or Old Cemetery. The Sevastopol Highway, here merging with the South Shore Highway, forms a boundary between Yalta and Vynohradne. Several vineyards here straddle the merged highway in the north. To the south of them is the town of Vynohradne with a mix of family homes and multi-story apartments. On its territory, from south to NW, are: a highway maintenance depot, farther northeast along the Bakhchesarai Highway (T 0117), a sanatorium, a dolphinarium, the Yalta Golf Club, the ‘Krym Beton’ cement plant, and the Yalta city cemetery.

The western segment from Yalta center follows Kirov Street towards Kuibysheve. The area is predominantly residential with a mix of family homes and multi-story apartment buildings with clusters of services, high rise apartments, some institutions, sanatoria and hotels. To the north of Kirov Street, proceeding west from the ‘Maharach’ Scientific Research Institute of Grape-growing and Winemaking, there are two units of Kirov Sanatorium and a hotel; west of it, two medical facilities for children: infectious diseases and reanimation; nearby the Institute of Economics and Management; and west of it the wooded Baturyn Square. Further west on Kirov Street, within a cluster of old buildings (former Autka) stands the Greek Church of the Holy Martyr Theodore Tiron. Just east of it is Middle School No. 4 (where Ukrainian language was taught) and beyond it, Yalta Medical College. West of this cluster, on the S side of Kirov Street, is the Anton Chekhov House Museum with its small orchard, and on the N side, a wooded Chekhov Square with a monument to the writer at its entrance. Farther west, from Kirov Street the Bolshevists Street branches to the NW, crosses the South Shore Highway and leads to a suburb with vineyards, grape processing, several hostels and, on its east side, a single-family house neighborhood. Crossing the highway to the WNW, Kirov Street exits Yalta city limits into Kuibysheve, where it follows the north bank of the Uchan-Su with a crossing to its south bank to access the Yalta Zoo and next to it, the Glade of Fairy Tales Museum and on, to a mountain village of hostels and a hotel.

The middle segment of Yalta is centered on the winding Voikov Street, bound by Shchors Street in the west and Sadova Street in the east. It has some old residential quarters, abundant parks, museums and a memorial on hills. Farther north are newer residential and, north of the highway, industrial uses. The main memorial complex is the ‘Hill of Glory,’ (est 1967) high on a hill overlooking Yalta. Access to it was facilitated with the construction (1967) of a double cable car facility lifting visitors from the Lenin Embankment near the Tavrida Hotel to the viewing platform and an exhibition hall. East of the memorial, on Pavlenko Street, is the K. Trenev and P. Pavlenko Literary Memorial Museum. North of it is the Armenian Surb Ripsime Church. Farther north, along the South Shore Highway there are services for motorists. North and west of the highway, as it loops to the north, are some residences, services, industries, and retail outlets.

The northeastern segment of Yalta is centered on the Derekoika River. It extends north from the city center to what were the villages of Derekoi and, beyond the South Shore Highway, Ai-Vasil (Vasylivka). The southernmost part of the segment comprises of a mixture of mostly residential, some commercial and institutional uses.

Along Kyiv Street the uses alternate between high rise residential and commercial, to the Central (Derekoi) Market. Along Moscow Street, north of the central market are residential apartments with shops and services, Middle School No. 9, a block of apartment buildings, and at the merging of Rudansky Street a triangular Taras Shevchenko Park with a statue of Taras Shevchenko. Along the winding Sverdlov Street, north of Rudansky Square, is a mix of residential buildings with greenery; where the street turns to the NE, there is a large park-like Ministry of Defense Sanatorium. It contains, on the south side, the Count Mordvinov Castle with a Vladimir Lenin monument in front of it, and other large buildings; in the middle is the Sanatorium Dining Hall; at the northeast end, the Princess Bariatynsky Mansion. Within the former Derekoi village the area is predominantly residential with hostels and services. Along Sadova Street there is a simple church at Kyiv Lane and two hostels; farther north, on its west side, Middle School No. 1, and ends at a neighborhood of small streets with individual family homes. Along Kyiv Street north of the Central (Derekoi) Market is a mix of housing with shops, and the Medrese Mosque. On the east side of Moscow Street, north of Shevchenko Park, is a neighborhood of residential apartments with post office and other services. Near Sverdlov Street, NE of the Ministry of Defense Sanatorium and close to the South Shore Highway, there are four apartment neighborhoods.

The former Ai-Vasil (Vasylivka), now part of the city of Yalta, lies north of the South Shore Highway at the headwaters of the Bola. Since Kyiv and Moscow streets both end at the highway, three separate streets from the highway enter Ai-Vasil. From west to east, they are: Izobilnaia, the central Dmitrii Ulianov, and the trolleybus depot access street. Near the entrance of the winding Dmitrii Ulianov Street, on its west side, is the Crimean Tatar cemetery. Ai-Vasil consists of single family homes, has basic services: stores, a post office, a medical dispensary, near its center School No. 8 (where instruction included Crimean Tatar language), and east of center, on Repin Street, the Orta Jami mosque. In the southeast corner, separated by the Huva River, is the Yalta trolley bus maintenance depot.

The east-northeastern segment of Yalta extends from the Saint John Chrysostom Church in the old city along Polikurov and Mukhin streets towards Masandra. North, along Mukhin Street, are large residences and hotels (W side) and a guest house in the wooded remains of the memorial cemetery (E side); then, turning northeast, beyond some apartments (W side) and houses (E side) the Sechenov Institute of Medical Climatology (NW side) and the Yalta Film Studio (SE side). Beyond this point, Mukhin Street passes into Masandra with its residential apartment buildings, but to the SE, Masandra Park is within Yalta city limits. Within Masandra, the Masandra winery is located near the west end of the town, north of the South Shore Highway. The Masandra Palace stands just beyond the northeast built-up area of Masandra, in a wooded area, where former Joseph Stalin’s ‘cottage’ (with meeting rooms) is hidden from view.

The eastern coastal segment extends along Drazhynsky Street beyond the old part of the city toward Vidradne. The street connects new resorts (on the S side, along the seashore) offering direct access to beaches. At the city limits, on the N side, with direct access to Masandra Park, is a huge Yalta Intourist hotel and entertainment complex with a theater, 3 movie theaters and a zoo ‘Planet of the Monkeys and Wild Cats.’ It has many pools for adults and children and 4 beach ball courts. There is even a helicopter pad. Beyond the city limits, west of the Vidradne village, is a new small Yalta freight port, equipped with cranes, its basin dredged and sheltered from the east and south by a breakwater.

Public transport. Yalta’s public transport is by buses, trolleybuses, and taxis; tickets for air and rail transport may be purchased locally, but the airport and train station are about 80 km away at Simferopol. Passenger cruises along the coast or scheduled destinations are made from the Yalta passenger port. Freight is now handled at the Yalta freight port and trucked locally. The city is connected by the coastal highways: E 105 to the east by way of Alushta then north to Simferopol, capital of the Crimean Autonomous Republic, and west, H 19, to Sevastopol.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jalta 1:166,000, 1: 25,200 (Wagner & Debes, Leipzig 1911)

Tverdokhlebov, I. ‘Yalta,’ Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukrainy vol 3 (Kyiv 1993)

Ivanets', A. ‘Yalta,’ Entsyklopediia istorii Ukrainy vol 10 (Kyiv 2013)

Karta Ialty (2023) https://kartaukrainy.com.ua/Yalta

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2024.]

.jpg)