Tychyna, Pavlo

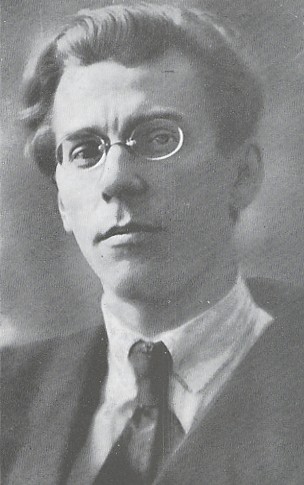

Tychyna, Pavlo [Тичина, Павло; Tyčyna], b 27 January 1891 in Pisky, Kozelets county, Chernihiv gubernia, d 16 September 1967 in Kyiv. Poet; recipient of the highest Soviet awards and orders; member of the VUAN and the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (now NANU) from 1929; deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR from 1938 and its chairman in 1953–9; deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from 1946; director of the Institute of Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR in 1936–9 and 1941–3; and minister of education of the Ukrainian SSR in 1943–8. He graduated from the Chernihiv Theological Seminary in 1913. His first poems were in part influenced by Oleksander Oles, Mykola Vorony, and Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. His first extant poem is dated 1906 (‘Synie nebo zakrylosia’ [The Blue Sky Closed]), and the first one published (‘Vy znaiete, iak lypa shelestyt'?’ [You Know How the Linden Rustles?]) appeared in Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk in 1912. In 1913 Tychyna enrolled at the Kyiv Commercial Institute, and while a student, he worked on the editorial boards of the newspapers Rada (Kyiv) and Svitlo (Kyiv). Later he worked for the Chernihiv zemstvo administration.

His first collection of poetry, Soniashni kliarnety (Clarinets of the Sun, 1918; repr 1990), is a programmatic work, in which he created a uniquely Ukrainian form of symbolism and established his own poetic style, known as kliarnetyzm (clarinetism). Finding himself in the center of the turbulent events during Ukraine's struggle for independence, Tychyna was overcome by the elemental force of Ukraine's rebirth and created an opus suffused with the harmony of the universal rhythm of light.

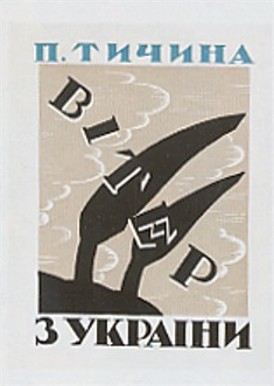

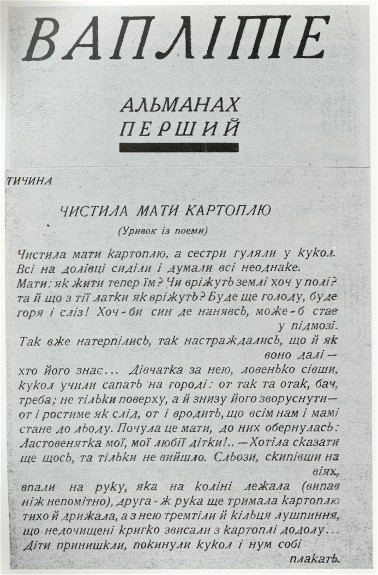

During the early years of the Bolshevik occupation of Ukraine, marked by terror, ruin, famine, and suppression of the national uprising, Tychyna maintained his position as an independent poet and quickly established himself as the leading Ukrainian poet. His pre-eminence is evident in the collections Zamist’ sonetiv i oktav (Instead of Sonnets and Octaves, 1920), Pluh (The Plow, 1920) and V kosmichnomu orkestri (In the Cosmic Orchestra, 1921), the poem ‘Skovoroda’ (the first part of which appeared in Shliakhy mystetstva, 1923, no. 5), and Viter z Ukraïny (The Wind from Ukraine, 1924), dedicated to Mykola Khvylovy. In 1923 he moved to Kharkiv and joined the organization Hart and, in 1927, Vaplite. His membership in the latter organization and his poem ‘Chystyla maty kartopliu’ (Mother Was Peeling Potatoes) provoked harsh official criticism, and he was accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism.’

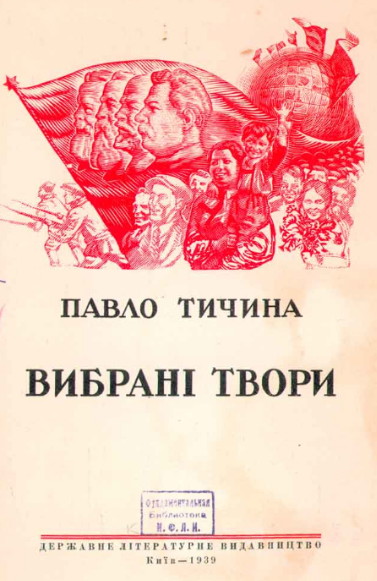

Soon after, Tychyna capitulated to the Soviet regime and began producing collections of poetry in the socialist-realist style sanctioned by the Party. They included Chernihiv (1931) and Partiia vede (The Party Leads, 1934). The latter collection has symbolized the submission of Ukrainian writers to Stalinism. The titles of his subsequent collections reflect the spirit of apologia for Joseph Stalin, including Chuttia iedynoï rodyny (Feelings of One Unified Family, 1938), for which he was awarded the Stalin Prize for literature in 1941, Pisnia molodosti (Song of Youth, 1938), and Stal’ i nizhnist’ (Steel and Tenderness, 1941). Abstract and expressionistic, his Stalinist poetry consists of kinetic iambs that push inexorably and bluntly forward, mimicking the Party line of the day.

The Second World War intensified those features of Tychyna's poetry, and gave rise to a patriotic combativeness, as manifested in My idemo na bii (We Are Going into Battle, 1941), Peremahat’ i zhyt’ (To Conquer and to Live, 1942), Tebe my znyshchym—chort z toboiu (We Will Destroy You—To Hell with You, 1942), and Den’ nastane (The Day Will Come, 1943). The titles of Tychyna's many postwar collections suggest their content: Zhyvy, zhyvy, krasuisia (Live, Live, and Be Beautiful, 1949), I rosty, i diiaty (To Grow and to Act, 1949), Mohutnist’ nam dana (Might Has Been Given Us, 1953), Na Pereiaslavs’kii radi (At the Pereiaslav Council, 1954), My svidomist’ liudstva (We Are the Consciousness of Humanity, 1957), Druzhboiu my zdruzheni (By Friendship We Are Bound, 1958), Do molodi mii chystyi holos (My Clear Voice Speaks to Youth, 1959), Bat’kivshchyni mohutnii (To the Mighty Fatherland, 1960), Zrostai, prechudovyi svite (Grow, O Wonderful World, 1960), Komunizmu dali vydni (The Horizons of Communism Are in Sight, 1961), and Topoli arfy hnut’ (Poplars Bend the Harps, 1963). He also wrote Virshi (Poems, 1968) and other collections.

Tychyna did not take part in the Ukrainian cultural revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s, and he even attacked the shistdesiatnyky. The poetry of the last decade before his death is full of glorification of the Party, of the new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, and of heroes of socialist labor, collective farms, and so on. During Leonid Brezhnev's repressive regime after Khrushchev's death Tychyna's creation sounded anachronistic and self-parodying. Occasionally, however, there were flashes of his former talent, as in the poem ‘Pokhoron druha’ (Funeral of a Friend, 1942) and some fragments in a collection published posthumously, V sertsi moïm (In My Heart, 1970), and particularly in the philosophical poem Skovoroda, which was never completed but was published posthumously, in 1971.

Tychyna's poetry before his capitulation to the regime represented a high point in Ukrainian verse of the 1920s. It is marked by a synthesis of 17th-century baroque and 20th-century symbolist styles. Some of the greatest advances in European poetry can be found in his ‘clarinetism,’ in its drawing upon the irrational elements of the Ukrainian folk lyric, its striving to be all-encompassing, its pervasive tragic sense of the eschatological, its play of antitheses and parabola, its asyndetonal structure of language, and other features.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nikovs'kyi, A. Vita nova (Kyiv 1919)

Maifet, H. Materiialy do kharakterystyky tvoriv Pavla Tychyny (Kharkiv 1926)

Iurynets’, V. Pavlo Tychyna (Kharkiv 1928)

Lavrinenko, Iu. Tvorchist’ Pavla Tychyny (Kharkiv 1930)

Boiko, I. Pavlo Tychyna: Bibliohrafichnyi pokazhchyk (Kyiv 1951)

Barka, V. Khliborobs’kyi orfei, abo Kliarnetyzm (New York 1961)

Novychenko, L. Poeziia i revoliutsiia: Tvorchist’ Pavla Tychyny v pershi pisliazhovtnevi roky, rev edn (Kyiv 1968)

– Spivets’ novoho svitu: Spohady pro Tychynu (Kyiv 1971)

Lavrinenko, Iu. Na shliakhakh kliarnetyzmu (New York 1977)

Halchenko, S. Tekstolohiia poetychnykh tvoriv P.H. Tychyny (Kyiv 1990)

Tel’niuk, S. Molodyi ia, molodyi: Poetychnyi svit Pavla Tychyny (1906–1925) (Kyiv 1990)

Ivan Koshelivets

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)