Solovets Islands

Solovets Islands [Russian: Соловецкие острова; Solovetskie ostrova]. A penal colony in the White Sea, Arkhangelsk oblast, Russian Federation. With an area of 347 sq km, the islands are largely covered with forest and many lakes and swamps. The climate is cold and damp.

In the 1420s and 1430s, monks settled on the islands; they had become a major outpost of Muscovite monastic life in the far north by the end of the 16th century. A strategic frontier fortress was built there. Until 1903 the islands were used by the tsars as a prison or place of banishment for political and religious offenders, but there were seldom more than a few dozen prisoners at one time. Among them were Ukrainians: some confederates of Vasyl Kochubei and Ivan Iskra, who had denounced Hetman Ivan Mazepa to the tsar, and who were interned there in 1708–12; some of Mazepa's supporters after 1709, including the general osaul Dmytro Maksymovych and the colonel Ya. Pokotylo of the Serdiuk regiment; the archimandrite Hedeon Odorsky and the protopriest (of Lokhvytsia) Ivan Rohachevsky in 1712; Petro Kalnyshevsky, the last Kish otaman of the New Sich, in 1776–1801; and Yurii Andruzky, a member of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, in 1850–4.

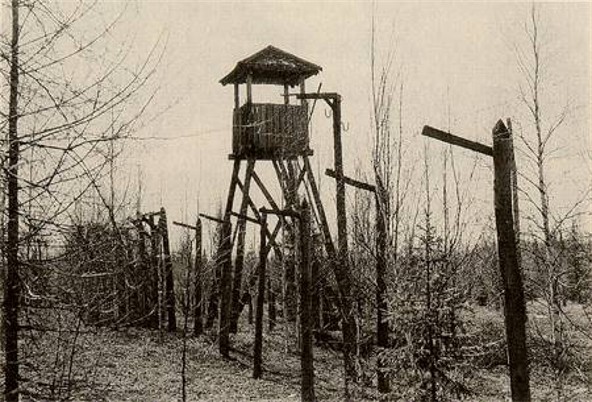

Most of the monks evacuated the islands after the Russian Revolution of 1917, and in 1923 the Bolsheviks established the Solovets Special Purpose Camp there, modeled on prisoner of war camps. Later it became part of the Northern Special Purpose camp complex, and still later, Section Eight of the White Sea–Baltic camp complex. In 1937 the camp in the Solovets Islands was renamed the Solovets Special Purpose Prison of the Main Administration of State Security of the USSR (see Concentration camps). For most of the 1920s the regime in the camp was relatively mild, and the number of prisoners relatively small. With the onset of the Stalinist terror, however, the Solovets Islands were packed with prisoners living in severe conditions, subjected to cold, hunger, punishment cells, and beatings. In 1931–3 many prisoners were sent to work on the White Sea Canal. Late in 1938 the prisoners were evacuated from the Solovets Islands to other camps, and the islands became a naval base.

Ukrainians in the camp in the mid-1920s were primarily Petliurists (see Symon Petliura), anti-Bolshevik insurgents, and clergymen. During dekulakization and collectivization in 1928–33 masses of Ukrainian peasants were exiled to the islands; among them were 325 peasants arrested for cannibalism during the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3. Arrests in the early 1930s, following the Trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine, brought much of the non-Communist Ukrainian intellectual elite to the camp as well as thousands of activists of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church. In 1933, Ukrainian Communists also began to fill the camps.

Among prominent Ukrainians who were interned in the Solovets Islands were the physician and political activist Arkadii Barbar; the Communist poet Vasyl Bobynsky; Volodymyr Chekhivsky, leader of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers' party and later of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church; the writer and critic Hryhorii Epik; the poet Pavlo Fylypovych; the historian Yosyf Hermaize; the writer and Communist activist Myroslav Irchan; the Socialist Revolutionary Pavlo Khrystiuk; the Futurist poet Hryhorii (Heo) Koliada; Les Kurbas, the director of the Berezil theater; the writer and political figure Antin Krushelnytsky; the playwright Mykola Kulish; the writer Mykola Liubchenko; the writer Vasyl Mysyk; the literary historian Mykhailo Novytsky; Mykola Pavlushkov (arrested as head of the Association of Ukrainian Youth); Semen Pidhainy, who later did much to document the history of the Solovets camps; the writers Valeriian Pidmohylny, Yevhen Pluzhnyk, and Klym Polishchuk; Mykhailo Poloz (former commissar of finances of Soviet Ukraine); the geographer Stepan Rudnytsky; the writer Mykhailo Semenko (a leading exponent of futurism); S. Semko (former rector of the Kyiv Institute of People's Education); the literary historian Yevhen Shabliovsky; the writer Geo Shkurupii; Oleksander Shumsky, whose name became synonymous with Ukrainian national communism; the historian Mykhailo Slabchenko; the writer Oleksa Slisarenko; the prominent CP(B)U activist P. Solodub; the hygienist Volodymyr Udovenko; the poet and journalist Marko Vorony; the writer Vasyl Vrazhlyvy; the Marxist historian Matvii Yavorsky; the memoirist V. Yurchenko; and the Neoclassicist poet and critic Mykola Zerov.

From 1924 until 1930 (perhaps longer) the Solovets camp had its own journal, Solovetskie ostrova. After conditions in the Solovets camp became known in the West, the Soviets released a propaganda film, Solovki, which mendaciously depicted life in the prison camp.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Efimenko, P. ‘Ssyl’nye malorossiiane v Arkhangel’skoi gubernii 1708–1802 g.,’ KS, 1882, no. 9

Kol’chin, M. Ssyl’nye i zatochennye v ostrog Solovetskogo monastyria v XVI–XIX vv.: Istoricheskii ocherk (Moscow 1908)

Chykalenko, L. (ed). Solovets’ka katorha (dokumenty) (Warsaw 1931)

Pidhainy, Semen. Ukraïns’ka inteligentsiia na Solovkakh: Spohady 1933–1941 (Neu-Ulm 1947)

———., Islands of Death (Toronto 1953)

—‘Solowky Concentration Camp’ and ‘Portraits of Solowky Exiles,’ in Black Deeds of the Kremlin: A White Book, ed Semen Pidhainy et al (Toronto 1953)

Solzhenitsyn, A. The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, vol 2 (New York 1975)

Frumenkov, G. Uzniki Solovetskogo monastyria, 4th edn (Arkhangelsk 1979)

Kuziakina, Natalia. Theater in the Solovki Prison Camp (Luxembourg 1995)

Kulakovs’kyi, Petro; Smirnov, Heorhii; Shapoval, Iurii (eds). Ostannia adresa: Do 60-richchia solovets’koï trahediï, 2 vols (Kyiv 1997–8)

Robson, Roy R. Solovki: The Story of Russia Told Through Its Most Remarkable Islands (New Haven–London 2004)

Shevchenko, Serhii. Solovets'kyi rekviiem (Kyiv 2013)

Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993). The bibliography has been updated.]

.jpg)