Scythians

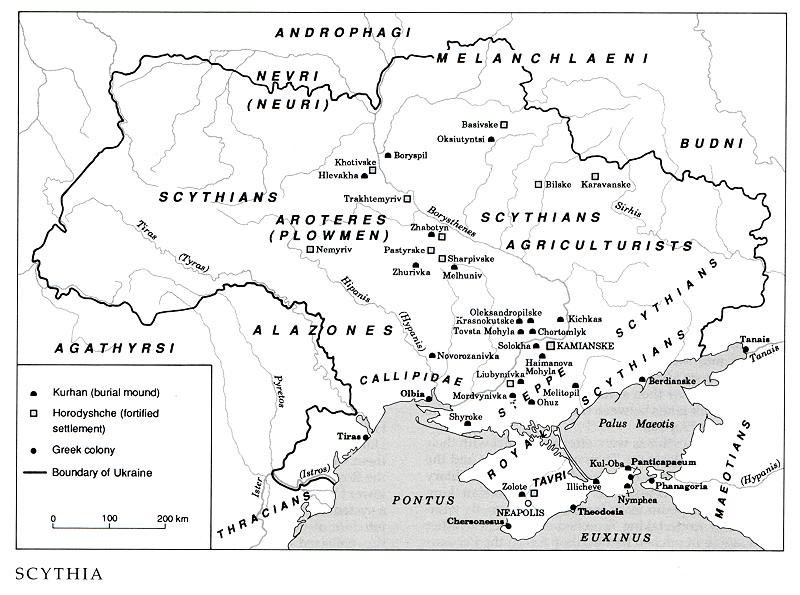

Scythians (скити, скіфи; skyty, skify). A group of Indo-European tribes that controlled the steppe of Southern Ukraine in the 7th to 3rd centuries BC. According to the most predominant theories, they first appeared there in the late 8th century BC after having been forced out of Central Asia. The Scythians were related to the Sauromatians and spoke an Iranian dialect. After quickly conquering the lands of the Cimmerians they pursued them into Asia Minor and established themselves as a power in the region. In the 670s BC they launched a successful campaign to expand into Media, Syria, and Palestine. They were forced out of Asia Minor early in the 6th century BC by the Medes, who had by then assumed control of Persia, and retreated to their lands between the lower Danube River and the Don River, known as Scythia.

The bellicose Scythians were often in conflict with their neighbors, particularly the Thracians in the west and the Sarmatians in the east. They faced their greatest military challenge around 513–512 BC, when the Persian king Darius I led an expeditionary force against them. By withdrawing and undertaking scorched-earth tactics rather than engaging in pitched battles, they forced the Persians to retreat in order to preserve their army. The event had a significant impact on subsequent Scythian development, for it confirmed their position as masters of the steppes and spurred on the political unification of the various tribes under the Royal Scythians. By the end of the 5th century BC the Kamianka fortified settlement, near present-day Nikopol, had been established as the capital of Scythia.

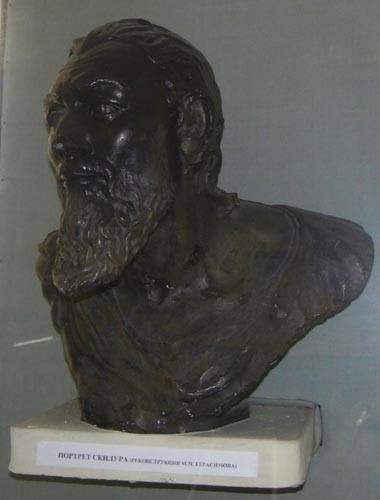

The Scythians reached their apex in the 4th century BC under King Ateas, who eliminated his rivals and united all the tribal factions under his rule. He waged a successful war against the Thracians but died in 339 BC in a battle against the army of Philip II of Macedonia. In 331 BC the Scythians defeated one of Alexander the Great's armies. Subsequently they began a period of decline brought about by constant Sarmatian attacks. They were forced to abandon the steppe to their rivals and re-established themselves in the 2nd century BC in the Crimea around the city of Neapolis. There they regained part of their strength and fought several times against the Bosporan Kingdom, and even managed to conquer Olbia and other ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. Continued attacks from the Sarmatians, however, further weakened the Scythians, and an onslaught by the Germanic Goths in the 3rd century AD finished them off completely. The Scythians subsequently disappeared as an ethnic entity through steady intermarriage with and assimilation into other cultures, particularly the Sarmatian.

The Scythians were divided into several major tribal groups. Agrarian Scythian groups lived in what is now Poltava region and between the Boh River and the Dnipro River. The lower Boh River region near Olbia was inhabited by Hellenized Scythians, known as Callipidae; the central Dnister River region was home to the Alazones; and north of them were the Aroteres. The kingdom was dominated by the Royal Scythians, a small but bellicose minority in the lower Dnipro River region and the Crimea that had established a system of dynastic succession. Their realm was divided into four districts ruled by governors who maintained justice, collected taxes, and gathered tribute from the Pontic city-states. A separate coinage, however, was not developed by the Scythians until quite late in their history. Their administrative apparatus was in fact quite loose, and the various Scythian groups handled most of their affairs through a traditional structure of tribal elders. Over time Scythian society became increasingly stratified, with the hereditary kings and their military retainers gaining an increasing amount of wealth and power. Although most Scythians were freemen, slaves were common in the kingdom.

The Scythians inhabiting the steppe were nomadic herders of horse, sheep, and cattle. Those in the forest-steppe were more sedentary cultivators of wheat, millet, barley, and other crops. (Some scholars believe that those agriculturists may have been the predecessors of the Slavs.) Scythian artisans excelled at metalworking in iron, bronze, silver, and gold (see Scythian art). The Scythians also engaged in hunting, fishing, and extensive trade with Greece through the Pontic city-states (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast); they provided grains, livestock, fish, furs, and slaves in exchange for luxury goods, fine ceramics, and jewelry.

The Scythians' military prowess was in large measure the result of their abilities as equestrian archers. They raised and trained horses extensively, and virtually every Scythian male had at least one mount. They lavished care and attention on their horses and dressed them in ornate trappings. Saddles and metal stirrups were not used by the Scythians, although felt or leather supports may have been. The foremost weapon of a Scythian warrior was the double-curved bow, which was used to shoot arrows over the left shoulder of a mounted horse. Warriors commonly carried swords, daggers, knives, round shields, and spears and wore bronze helmets and chain-mail jerkins. The Scythians became a potent force not only because of their impressive array of weapons and training but also because they shared a strong underlying military ethos and belonged to a warrior society that bestowed honors and spoils on those who had distinguished themselves in battle. That ethos was reinforced by the common rite of adopting blood brothers and the use of slain foes' scalps or skulls as trophies or drinking cups.

Because of their generally nomadic or seminomadic existence the Scythians usually had relatively few possessions. Those they did have were often of exquisite quality and craftsmanship and established the Scythians' reputation in the ancient world as devotees of finery (see Scythian art).

The Scythians never developed a written language or a literary tradition. They had a well-defined religious cosmology, however. Their deities included the fire goddess Tabiti, followed by Papeus (the ‘Father’), Apia (goddess of the earth), Oetosyrus (god of the sun), Artimpasa (goddess of the moon), and Thagimasadas (god of water). The Scythians did not build temples, altars, or idols to worship their deities, but they maintained a caste of soothsayers and believed strongly in witchcraft, divination, magic, and the power of amulets. Representations of Scythians and their gold ornaments suggest that they were the first people in history to wear trousers.

Scythian burial customs were elaborate, particularly among the aristocracy. A chieftain remained unburied for 40 days after his death. During that time his internal organs were cleansed, his body cavity was stuffed with herbs, and his skin was waxed. He was then paraded through his realm accompanied by a large retinue indulging in ostentatious lamentations. After 40 days he was interred in a large kurhan (up to 20 m high) together with his newly killed favorite wife or concubine, household servants, and horses, as well as weapons, amphoras of wine, and a large cache of goods. Lesser personages had less elaborate funerals. A common practice was the erection of anthropomorphic statues (see Stone baba) as grave markers.

For many years the memory of the Scythians was best preserved by Herodotus, who included a lengthy, basically factual account of them in his Histories. After the last Scythians had died out in the 3rd century AD, the tribes were largely forgotten. Interest in them was revived as a result of some spectacular finds in Scythian kurhans, starting with the Melgunov kurhan in 1763. The ensuing search for richer caches impeded archeological research on the more prosaic aspects of Scythian life until Soviet archeologists undertook work in that realm in the 20th century. Scythian archeological sites in Ukraine include the Bilsk fortified settlement, Kamianka fortified settlement, Karavan, Nemyriv fortified settlement, Pastyrske fortified settlement, and Sharpivka fortified settlement and Chortomlyk, Haimanova Mohyla, Kul Oba, Krasnokutskyi kurhan, Melitopol kurhan, Oksiutyntsi kurhans, Oleksandropil kurhan, Solokha kurhan, Starsha Mohyla, Tovsta Mohyla, and Zhabotyn kurhans and settlement.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Minns, E. Scythians and Greeks: A Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus (Cambridge 1913)

Rostowzew, M. Skythien und der Bosporus (Berlin 1931)

Sulimirski, T. Scytowie na Zachodniem Podolu (Lviv 1936)

Rice, T. The Scythians (London 1957)

Pasternak, Ia. Arkheolohiia Ukraïny (Toronto 1961)

Potratz, J.A.H. Die Skythen in Südrussland: Ein untergegangenes Volk in Südosteuropa (Basel 1963)

Smirnov, A. Skify (Moscow 1966)

Kovpanenko, H. Plemena skifs’koho chasu na Vorskli (Kyiv 1967)

Il’inskaia, V. Skify Dneprovskogo lesostepnogo Levoberezh’ia (kurgany Posul’ia) (Kyiv 1968)

Petrov, V. Skify: Mova i etnos (Kyiv 1968)

Vysotskaia, T. Pozdnie skify v Iugo-Zapadnom Krymu (Kyiv 1972)

Terenozhkin, A. (ed). Skifskie drevnosti (Kyiv 1973)

Artamonov, M. Kimmeriitsy i skify (ot poiavleniia na istoricheskoi arene do kontsa IV v. do n.e.) (Leningrad 1974)

Iakovenko, Ie. Skify Skhidnoho Krymu v V–III st. do n.e. (Kyiv 1974)

Khazanov, A. Sotsial’naia istoriia skifov: Osnovnye problemy razvitiia drevnikh kochevnikov evrazeiskikh stepei (Moscow 1975)

Chernenko, E. Skifskie luchniki (Kyiv 1981)

Kovpanenko, G. Kurgany ranneskifskogo vremeni v basseine r. Ros’ (Kyiv 1981)

Neikhardt, A. Skifskii rasskaz Gerodota v otechestvennoi istoriografii (Leningrad 1982)

Il’inskaia, V.; Terenozhkin, A. Skifiia VII–IV vv. do n.e. (Kyiv 1983)

Mozolevs’kyi, B. Skifs’kyi step (Kyiv 1983)

Kuklina, I. Etnogeografiia Skifii po antichnym istochnikam (Leningrad 1985)

Rolle, R. The World of the Scythians (London 1989)

Bohdan Kravtsiv, Andrij Makuch

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)