Romanticism

Romanticism. An artistic and ideological movement in literature, art, and music and a world view which arose toward the end of the 18th century in Germany, England, and France. In the beginning of the 19th century it spread to Russia, Poland, and Austria, and in the mid-19th century it encompassed other countries of Europe as well as North and South America. Romanticism, which appeared after the French Revolution in an environment of growing absolutism at the turn of the 19th century, was a reaction against the rationalism of the Enlightenment and the stilted forms, schemata, and canons of classicism and, at times, sentimentalism. Paramount features of romanticism were idealism, a belief in the natural goodness of the individual person, and, hence, the cult of feeling as opposed to reason; a predilection for the more ‘primitive’ expressions of human creativity as being closer to the fundamental goodness of the person and, hence, an enthusiasm for folk art, poetry, and songs; a belief in the perfectibility of the individual person and, hence, a predilection for change and the espousal of ‘striving’ as a mode of behavior; and a search for historical consciousness and an intensified learning of history (historicism), coupled at times with an escape from surrounding reality into an idealized past or future or into a world of fantasy. The Romantic world view fostered its own style and gave rise to specific genres of literature: ballads, lyrical songs, romances, and historical novels and dramas.

Certain elements of romanticism, especially those which emphasized the value of the folk, such as Johann Gottfried von Herder's notion of the importance of folklore in the development of literature, encouraged a resurgence of interest in folklore and history. The study of both resulted in a general reawakening of Slavic peoples, including the Ukrainians. The first manifestations of the influence of romanticism in Ukraine were the publications in Saint Petersburg of Oleksii Pavlovsky's Grammatika malorossiiskogo narechiia (The Grammar of the Little Russian Dialect) in 1818 and of Nikolai Tsertelev's Opyt sobraniia starinnykh malorossiiskikh pesnei (An Attempt at Collecting Ancient Little Russian Songs) in 1819—a collection remarkable not only for the songs but, more important, for its emphasis on the rich and unique nature of Ukrainian folk songs. Appreciation of Ukrainian folk songs was strengthened by the publication in Moscow in 1827 of Mykhailo Maksymovych's collection Malorossiiskie pesni (Little Russian Songs). In literature the precursor of Ukrainian romanticism was Petro Hulak-Artemovsky. His ballads, like Ukrainian romanticism in general, were less a protest against the rather insignificant classical movement in Ukraine (see Classicism) than a reaction against the prevalent concept that only burlesque and travesties could be written in the ‘peasant’ vernacular—the adjective aptly describes the status of the Ukrainian language in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century.

Also influential in the development of Ukrainian romanticism were the so-called ‘Ukrainian schools’ in Russian and Polish literature. In Russian literature the leading members of the ‘Ukrainian school’ were not only Russians (Kondratii Ryleev, F. Bulgarin) enthralled by the exotic nature of things Ukrainian (nature, history, folk mores, and folklore) but also Ukrainians who wrote in Russian (Orest Somov, Mykola Markevych, Yevhen Hrebinka, and, foremost among them, Nikolai Gogol). The Ukrainian school in Polish literature, with its fascination with Ukrainian ‘exotic’ themes, consisted of writers such as Antoni Malczewski, Józef Bohdan Zaleski, and Seweryn Goszczyński.

The interest in folklore and history spawned by romanticism in Ukraine produced a wealth of material: collections of folk songs by Mykhailo Maksymovych (1827, 1834, 1849), compilations of historical songs and dumas by Izmail Sreznevsky in Zaporozhskaia starina (1833–80), a gathering of folk oral literature by Platon Lukashevych (1836), and numerous publications of historical monuments and works, by Dmytro Bantysh-Kamensky, Osyp Bodiansky, Mykola Markevych, Apollon Skalkovsky, and others.

The first locus of Ukrainian romanticism was the Kharkiv Romantic School. The group was centered around I. Sreznevsky and consisted of poets such as Levko Borovykovsky, Amvrosii Metlynsky, Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Petrenko, and Oleksander Korsun. It published two almanacs, Ukrainskii al’manakh (1831) and Zaporozhskaia starina.

Contemporaneously with the Kharkiv Romantic School appeared the Ruthenian Triad in Galicia. It consisted of Ivan Vahylevych, Yakiv Holovatsky, and, primarily, Markiian Shashkevych and was most noted for the publication of the almanac Rusalka Dnistrovaia (The Dnister Nymph, 1836). The romanticism of the Ruthenian Triad lay in its promulgation of the folk language (ie, Ukrainian) in opposition to the prevalent yazychiie. The followers of the triad's program were such Galician authors as Mykola Ustyianovych and Antin Mohylnytsky, as well as Oleksander Dukhnovych in Transcarpathia.

The second phase of Ukrainian romanticism, which had a more pronounced national and political program that resulted in a greater variety of literary works, occurred in the late 1830s and early 1840s in Kyiv. The Kyivan group consisted of Mykhailo Maksymovych, Panteleimon Kulish, Taras Shevchenko, and the former members of the Kharkiv Romantic School A. Metlynsky and M. Kostomarov, who moved to Kyiv. The group's philosophical and ideological focus came from the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, whose Christian-Romantic program, expressed in Knyhy bytiia ukraïns’koho narodu (Books of the Genesis of the Ukrainian People), had been inspired by Kostomarov, and manifested itself most artistically in the messianic poetry of Shevchenko. Other expressions of that phase of Ukrainian romanticism can be found in the almanacs and miscellanies Kievlianin (1840, 1841, 1850), Lastôvka (1841), Snip (1841), Molodyk (1843, 1844), and Iuzhno-russkii sbornik (1848). Other writers tied to the Kyivan group of Romantics were Viktor Zabila from Chernihiv, Oleksander Afanasiev-Chuzhbynsky from Poltava, and the poet and editor Osyp Bodiansky, who lived in Moscow.

The third phase of Ukrainian romanticism centered around the journal Osnova (Saint Petersburg) (1861–2), published in Saint Petersburg by the former members of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood Vasyl Bilozersky, M. Kostomarov, and P. Kulish. Also part of that late Romantic phase are authors such as Oleksa Storozhenko, with his fantastic stories full of the more gory and Gothic folkloric motifs, poets such as Yakiv Shchoholiv, and the Bukovynian bard Yurii Fedkovych.

The poetry of Ukrainian romanticism can be divided, in general, into two streams: national-patriotic lyricism, based in the majority of the Ukrainian Romantic poets on an idealization of the heroic Cossack past, and subjective personal lyricism, found to a lesser degree in all of the poets but predominantly in such authors as Mykhailo Petrenko, Viktor Zabila, and Yakiv Shchoholiv. The Ukrainian Romantic movement differs from the Russian in the historicism of its epic genre, its idealization of the past, and its predilection for the songlike structure, with motifs of national as opposed to personal longing. Ukrainian romanticism is more akin to Polish romanticism.

Having discovered the importance of folk poetry and folk art in the development and growth of literature, and the importance of historical monuments and research for the development of national consciousness, Ukrainian romanticism also contributed to the independence of the Ukrainian literary language and to the perfection of poetic tropes. Nonetheless the Romantic poets, having chosen the ballad and the lyrical poem as the prime mode of expression, did little in other genres. The exceptions were the early epic poems by Taras Shevchenko, the single historical novel Chorna rada (The Black Council) by Panteleimon Kulish, and the valiant attempts at historical dramas by Mykola Kostomarov. But Ukrainian themes in the works of the Russian and Polish Romantics did much to popularize Ukraine, its culture and history, in the Western world.

Romanticism gave way in the second half of the 19th century to realism, with its naturalistic method and populist philosophy. Yet elements of romanticism began to appear again in the first decades of the 20th century, during the height of modernism. That ‘neoromanticism’ is characterized by a return to folklore as the source of inspiration (eg, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's Tini zabutykh predkiv [Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, 1911], Lesia Ukrainka's Lisova pisnia [The Forest Song, 1911], Hnat Khotkevych's Kaminna dusha [The Soul of Stone, 1911]), or to the personification of nature as a self-willed participant in human life (Olha Kobylianska's story ‘Bytva’ [Battle]). A type of neoromanticism also appeared in the Ukrainian literature of the 1920s in the poetic works of the so-called neo-Romantics Mykola Bazhan, Oleksa Vlyzko, Dmytro Falkivsky, and Volodymyr Sosiura; in the prose of Yurii Yanovsky; and in the concept of ‘vitaism’ (vitalized romanticism) of Mykola Khvylovy.

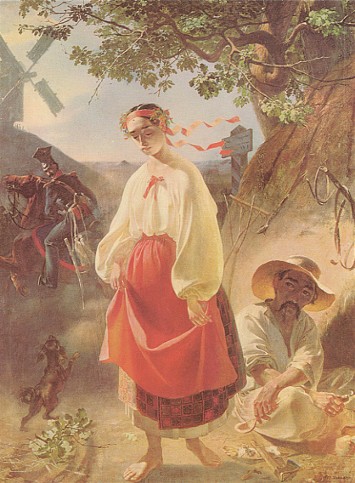

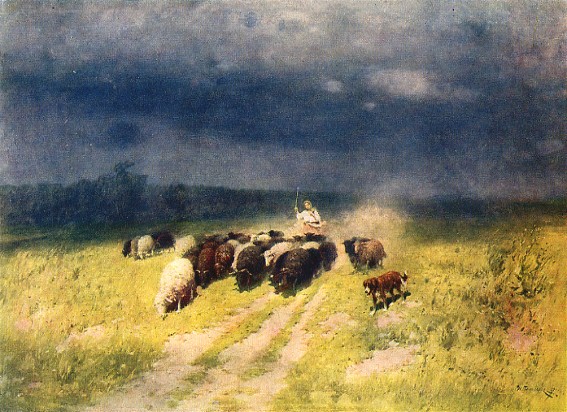

The ideas, themes, and subjects of romanticism had a profound influence on art toward the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries in Western Europe and in the Slavic countries neighboring on Ukraine. In Ukraine romanticism had its effect on the art of non-Ukrainians living in Ukraine, such as the Russian Vasilii Tropinin, the Armenian Ivan Aivazovsky, and the Poles Juliusz Kossak and A. Grottger. The influence of romanticism can also be seen in the early paintings of Taras Shevchenko and Kostiantyn Trutovsky, as well as in the works of the Ukrainian artists Ivan Soshenko, Apollon Mokrytsky, Opanas Slastion, Mykola Ivasiuk, Serhii Vasylkivsky, Mykola Pymonenko, and Amvrosii Zhdakha, among others.

Romantic influences in Ukrainian music, however, were meager and can be seen only in the works of some composers in the second half of the 19th century, such as Semen Hulak-Artemovsky, Mykola Lysenko, Viktor Matiuk, Sydir Vorobkevych, and Anatol Vakhnianyn, especially in their compositions to the words of Romantic poets. In theater the influence of romanticism was very small. Ukrainian historical plays did not achieve prominence, and only a Romantic sentimentality can be seen in the standard repertoire of ethnographic realism. Thus Ukrainian romanticism was predominantly a poetic phenomenon, the importance of which lies first and foremost in its contribution to the reawakening of Ukrainian national consciousness through the recaptured and idealized heroic past and rich and unique folkloric heritage.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shamrai, A. ‘Do pochatkiv romantyzmu,’ Ukraïna, 1929, nos 10–11

Čiževskij, D. On Romanticism in Slavic Literature (The Hague 1957)

Kotsiubyns’ka, M. ‘Poetyka Shevchenka i ukraïns’kyi romantyzm,’ in Zbirnyk Shostoï naukovoï shevchenkivs’koï konferentsiï (Kyiv 1958)

Prykhod’ko, P. Shevchenko i ukraïns’kyi romantyzm 30–50-kh rr. XIX st. (Kyiv 1963)

Volyns’kyi, P. Ukraïns’kyi romantyzm u zv'iazku z rozvytkom romantyzmu v slov'ians’kykh literaturakh (Kyiv 1963)

Kyrchiv, R. Ukraïnika v pol’s’kykh al’manakhakh doby romantyzmu (Kyiv 1965)

Shevel’ov, Iu. ‘Z istoriï ukraïns’koho romantyzmu,’ in Orbis Scriptus: Dimitrij Tschizevskij zum 70 Geburtstag (Munich 1966)

Ukraïns’ki poety romantyky 20–40-kh rokiv XIX st. (Kyiv 1968)

Guliaev, N. (ed). Voprosy romantizma v sovetskom literaturovedenii: Bibliograficheskii ukazatel’ (Kazan 1970)

Kyryliuk, Ie. Ukraïns’kyi romantyzm u typolohichnomu zistavlenni z literaturamy zakhidno- i pivdennoslov'ians’kykh narodiv: Persha polovyna XIX st. (Kyiv 1973)

Kozak, S. U źródeł romantyzmu i nowoczesnej myśli społecznej na Ukrainie (Wrocław–Warsaw–Cracow–Gdańsk 1978)

Komarynets’, T. Ideino-estetychni osnovy ukraïns’koho romantyzmu (Lviv 1983)

Kovaliv, Iu. Romantychna styl’ova techiia v ukraïns’kii radians’kii poeziï 20–30-kh rokiv (Kyiv 1988)

Naienko, M. Romantychnyi epos: Liryko-romantychna styl’ova techiia v ukraïns’kii radians’kii prozi (Kyiv 1988)

Bohdan Kravtsiv, Danylo Husar Struk

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)