Romania

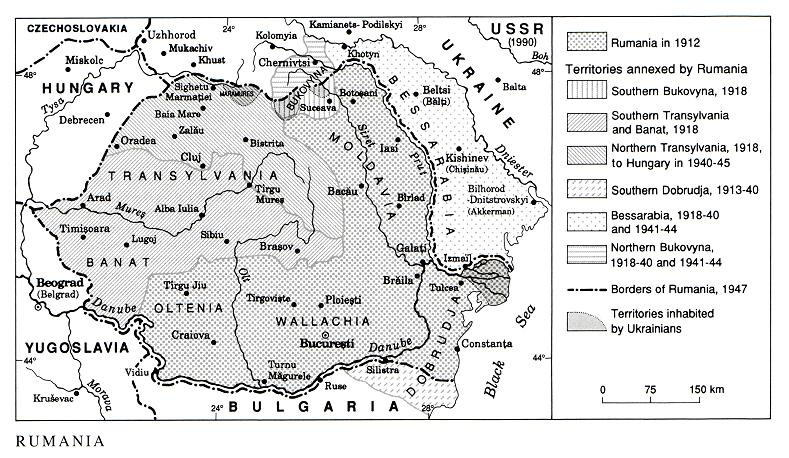

Romania or Rumania. A country in southeastern Europe (2011 pop 20,141,641) in the lower Danube River basin, situated between Hungary (west), Ukraine (north and east), Bulgaria (south, with the Danube as the border), and Serbia (southwest). Its capital is Bucharest. Its 237,500 sq km consists of sections of the eastern and southern Carpathian and Transylvanian Uplands, the Panon and Wallachian Lowlands to the west of the mountains, and the Moldavian and Dobrudja (Dobrogea) Uplands to the east. Its history is closely related to that of its historical neighbors: Bulgaria, Hungary, Austria, Austria-Hungary, Kyivan Rus’, the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Hetman state, the Russian Empire, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Turkey, and Ukraine. Parts of Romania (and at certain times, the entire country) were under the control of these states or were protectorates of them.

In the past, Romania was divided into three political formations: Moldavia (a country between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dnister River; its eastern section is known as Bessarabia), Wallachia or Muntenia to the south, and Transylvania to the west. The first two came together as Romania in 1861, and all three were united in 1918. Romanians also constitute a majority of the inhabitants in Moldavia (at present called Moldova). Moldavians was the official name given to Romanians living in the Russian Empire.

Ukrainians and Romanians share an arching border which is 900 km long. Both nationalities have in common Orthodoxy, the influence of Byzantine art and culture, and their struggle against Turks and Crimean Tatars. They also have some similar folk traditions. Political and cultural relations between the two were active in the 16th and 17th centuries, but they subsequently tapered off because neither had its own state. In fact Ukrainians and Romanians had virtually no direct political contact in modern times until after the First World War.

Until the creation of the Romanian state in 1859–61, Romanian-Ukrainian political relations were conducted mainly through Moldavia. Contacts with Wallachia were insignificant, and even more rare with Transylvania. In the 16th and 17th centuries Cossacks assisted Moldavia and Wallachia in their struggles against Turkey. M. Viteazul’s army in 1595 had 7,000 Cossacks. Bohdan Khmelnytsky signed a treaty with Moldavia and married his son, Tymish Khmelnytsky, to Roksana Lupu, the daughter of Vasile Lupu, a Moldavian hospodar. T. Khmelnytsky led 8,000 soldiers on a campaign to defend his father-in-law, but was defeated at the Finta River on 17 May 1653 and killed on 15 September 1653 in the Battle of Suceava. The increasing control of Muscovy over Ukraine and of the Ottoman Empire over Romania that followed ended any possibility of further relations.

The Austrian annexation of Bukovyna in 1774 and the Russian annexation of Bessarabia in 1812 brought Ukrainians and Romanians into direct contact with one another. In Bessarabia, where the national consciousness of neither people was well developed, conflict between the two did not arise. In contrast, ethnic relations in Bukovyna became increasingly strained through the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the Ukrainians began to become politically active and demand certain national rights. The balance of power in Bukovyna shifted dramatically in 1918, when the crown land was ceded to the new Romanian state. Ukrainians, now considered to be errant Romanians who had forgotten how to speak their ‘native’ language, came under relentless attack: all schools were Romanianized, the use of the Ukrainian language in the courts and in public offices was banned, the Ukrainian chairs at Chernivtsi University were abolished, and many Ukrainian societies (including Ruska Besida in Bukovyna) were closed down. Bukovynian Ukrainians were extremely dissatisfied with this harsh treatment. In 1940 the Romanians withdrew from Bessarabia and North Bukovyna in response to an ultimatum from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which subsequently occupied the region.

In 1917–21 the Ukrainian National Republic sought to establish normal relations with Romania. In January 1918 A. Halip was sent on a public relations mission there. Subsequent representatives of Ukrainian governments included Mykola Halahan, V. Dashkevych-Horbatsky, and Kost Matsiievych (1919–22). Romanian diplomats in Ukraine included the generals Coanda and Concescu. Romania recognized the Ukrainian state de facto and entered into trade agreements with it. At one point Romania agreed to supply arms in exchange for other goods, but the collapse of the Ukrainian front in 1919 put an end to these plans. Some conflicts arose over Romania’s military occupation of Bessarabia in March 1918 and of northern Bukovyna in November 1918, and there was a rearguard attack on the Ukrainian Galician Army in May 1919 during a brief Romanian invasion of Pokutia.

During the interwar era the Romanian government did not foster diplomatic or other ties with the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a whole. At the same time it took care not to antagonize the Soviets and was reluctant to grant asylum to refugees from Ukraine. In 1940 Romania ceded North Bukovyna to the USSR. After having allied itself with Nazi Germany, Romania invaded Bukovyna, Bessarabia, and Transnistria in 1941 and controlled these regions until 1944, when they again came under Soviet rule. That same year Romania was overrun by the Soviet Army troops and became an Eastern-bloc satellite of the USSR, and closely began to follow the latter’s edicts about the Ukrainian question. Romania maintained a consulate in Kyiv.

In the realm of culture, Ukraine’s most significant ties to Romania were with Moldavia, although it also had connections with Wallachia (most notably Petro Mohyla’s assistance with the establishment of printing presses). U. Năsturel, a scholar of the 17th century, had close relations with Kyiv and imitated Ukrainian writers in his works. Meletii Smotrytsky’s grammar was published in Snagov (1697) and Râmnic (1755), and it was influential in the preparation of the first Romanian grammars. Pamva Berynda’s Leksykon slavenorosskyi (Slavonic-Ruthenian Lexicon) was published in five editions in Romanian translation. U. Năsturel, V. Măzăreanu (1710–90, archimandrite, writer, and reformer of Moldavian schools), G. Banulescu-Bodoni (metropolitan of Kyiv, and then of Moldavia and Wallachia), M. Stefanescu (a bishop), and other Wallachian leaders studied at the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. Paisii Velychkovsky, who became hegumen of the Neamţ Monastery in 1779, revived Romanian monastic life and was active in publishing and other cultural concerns. V. Costache (1768–1846), the metropolitan of Moldavia, corresponded with Ukrainian church leaders and published the Kyivan Sinopsis in Romanian in 1837.

In the 19th century a number of Romanian writers and scholars focused on Ukrainian subjects. A. Hâjdău (1811–74) studied at Kharkiv University, and published a biography of Hryhorii Skovoroda in 1835. His son, B. Petriceicu Haşdeu (1838–1907), was born in Khotyn, studied in Kharkiv, and wrote on Ukrainian themes. His Ioan-Vodă cel Cumplit (Ioan-Raging Prince, 1865) was based on Leontii Bobolynsky’s chronicle. N. Gane’s (1838–1916) Domniţa Roxana (Princess Roksana) was an original rendering of Tymish Khmelnytsky’s marriage to Roxana Lupu. G. Asachi (1788–1869), Boleslav Hâjdeu (1812–86), and C. Stamati (1785–1869) were other writers interested in Ukraine, as were the Slavists I. Bogdan (1864–1919) and I. Bianu (1856–1935). C. Dobrogeanu-Gherea (1855–1920) studied at Kharkiv University, became the leader of the Romanian Social Democratic party, and popularized the work of Taras Shevchenko in Romania.

Among the Romanians interested in the Ukrainian question in the 20th century were the community leader Z. Arbore; the writers E. Bogdan, L. Fulga, Mihal Sadoveanu, and M. Sorbul; the literary scholars E. Camilar and Mahdalyna Laslo-Kutsiuk; the historians G. Bezviconi, P. Constantinescu-Iaşi, M. Dan, Eudoxiu Hurmuzachi, Nicolai Iorga, I. Nistor, S. Ciobanu, P. Panaitescu, D. Strungaru, and A. Vianu; and the linguists T. Macovei, G. Mihăila, E. Petrovici, M. Stefanescu, and E. Vrabie. Romanian scholars have devoted most of their attention to the 17th century in particular. Many articles on Ukrainian-Romanian relations appeared in the 17 issues of Romanoslavica, which were published in 1958–70 in Bucharest before a change in Romanian government policy toward national minorities led to its demise. Emigré scholars who focused on the subject include G. Ciorănescu, G. Nandriş, and E. Turdeanu. Romanian-Ukrainian relations have been studied in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic by V. Haţak, N. Mokhov, S. Popovici, and I. Varticean.

Ukrainian scholars and writers who delved into Romanian-Ukrainian influences included the historians M. Cheredaryk, Volodymyr Hrabovetsky, Omelian Kaluzhniatsky, Oleksander Yu. Karpenko, Hryhorii Koliada, N. Komarenko, Myron Korduba, Yevhen Kozak, V. Mylkovych, Antin Petrushevych, O. Romanets (who was interested in Ukrainian-Moldavian relations), Isydor Sharanevych, Fedir Shevchenko, and Yurii Venelin (who studied Slavic manuscripts in Romanian libraries); the ethnographers and historians Mykhailo Drahomanov, Ivan Franko, Ivan Reboshapka, Fedir Vovk, and V. Zelenchuk; the musicologists Klyment Kvitka and Sydir Vorobkevych; the art critic Vsevolod Karmazyn-Kakovsky; the linguists Petro Buzuk, I. Doshchivnyk, Oleksa Horbach, Yu. Kokotailo, Ivan Ohiienko, Mykola Pavliuk, S. Semchynsky, Ivan Sharovolsky, Dmytro Sheludko, Vasyl Simovych, and Roman Smal-Stotsky; and the writers Yurii Fedkovych, Hnat Khotkevych, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Andrii Miastkivsky, V. Pianov, Yakiv Stetsiuk, and Sydir Vorobkevych.

Romanian literature is largely inaccessible to Ukrainian readers, but several translations into Ukrainian have been made. The novels translated include B. Haşdeu’s Răzvan şi Vidra, L. Rebreanu’s Ion, and Mihail Sadoveanu’s Mitrea Cocor and Nicoară Potcoavă. Maksym Rylsky, Ya. Shporta, Volodymyr Sosiura, and Mykola Tereshchenko contributed to an anthology of translations of M. Eminescu’s poetry, and other verse in Ukrainian translation includes that of V. Tulbure and C. Petrescu. I.L. Caragiale’s drama O scrisoare pierdută (The Lost Letter) has also appeared in translation. A. Miastkivsky and V. Pianov have translated a number of Romanian works into Ukrainian.

V. Tulbure translated Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar into Romanian, and it was published with an introduction by M. Sadoveanu in 1957. Other Ukrainian writers whose works have been rendered in Romanian include Ivan Drach, Volodymyr Drozd, Ivan Franko, Oles Honchar, Yevhen Hutsalo, Olha Kobylianska, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Lesia Ukrainka, Dmytro Pavlychko, Valerii Shevchuk, Vasyl Stefanyk, Mykhailo Stelmakh, Pavlo Tychyna, and Yurii Yanovsky.

In 1958 the Ukrainian Society for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries began staging days of Romanian culture in Kyiv and other cities of Ukraine. Various Romanian soloist musicians and the National Theater gave performances. Romanian films were shown, and exhibitions of Romanian art and books were organized. There was a Ukrainian department of the Soviet-Romanian Friendship Society (established in 1959), but it was not very active.

Economic ties. From the mid-17th century, merchants from Kyiv, Nizhyn, Pereiaslav, and Romny were engaged in vigorous trade with Moldavia and Wallachia. Wine was an important Romanian export (2,769 barrels in 1759), as were nuts, salt, salted fats, and fruits. Ukrainian exports included manufactured goods, furs, agricultural produce, and various raw materials. In the 19th century imports from Moldavia included wheat, corn, and fruits; Ukrainian exports consisted mainly of sugar, coal, and livestock.

After 1918 trade between Romania and Ukraine came to a virtual standstill; it resumed only after 1950. Ukraine had a negative trade balance with Romania. Exports to Romania constituted only 8 percent of its total exports, whereas Romania sent 20 percent of its exports to Ukraine. In the 1970s Ukraine imported milled lumber (approximately 260,000 cu m annually, 12 percent of the Romanian total), petroleum products (approximately 460,000 tonnes annually), steel freight cars, agricultural machinery, chemical supplies, furniture, clothing, shoes, canned goods, and fruit. Ukraine mainly exported raw materials, such as iron ore (in 1971, 50 percent of Romania’s imports), coke (29 percent), hydroelectric power (16 percent), cast iron (12 percent), and coal (7 percent). Other exports included metal rollers, lathes, conducting material, and small-sized boats.

Ukrainians in Romania. Before 1918 Ukrainians settled primarily in the northern Dobrudja region, in the Danube River delta (see also Danubian Sich). The settlements flowed directly out of the Ukrainian demographic territory in South Bessarabia and had a total population of around 20,000. About 50,000 Ukrainians also lived in northern Moldavia in the Dorohoi and Botoşani districts, where they were the predominant group until the 17th century. Today the Ukrainian language and folk customs have been only partially preserved, in villages such as Căndeşti, Rogojeşti, and Semenicea.

After the First World War Ukrainian ethnographic lands in Bukovyna, Bessarabia, and the Maramureş region (a small section of Transcarpathia) were ceded to Romania, in addition to a number of Ukrainian ‘oases,’ such as Banat, that had previously belonged to Hungary. A total of about 1.2 million Ukrainians lived in Romania, which figure included approximately 800,000 on Ukrainian ethnographic territory. Until 1944 they were subjected to discrimination and socioeconomic exploitation.

Many Ukrainians, particularly teachers and civil servants, were transferred from Bukovyna and Bessarabia to cities in the Romanian heartland in an effort to speed up the pace of Romanianization. In spite of these conditions, efforts were made to maintain Ukrainian community life.

The Public Relief Committee of Ukrainian Emigrants in Romania was established in 1923; it was headed by Kost Matsiievych, with V. Trepke as vice-president and D. Herodot as secretary. The committee co-ordinated the work of 10 émigré communities, the largest of which was the Community of Ukrainian Emigrés in Bucharest. Also active in Bucharest were the Union of Ukrainian Emigré Women (headed by N. Trepke), the Society of Ukrainian Veterans in Romania (headed by H. Porokhivsky), and the Union of Ukrainian Farmers in Bucharest (a hetmanite group founded in 1921, headed by P. Novitsky). Ukrainian students in postsecondary schools in Bucharest established the Zoria society, which was active in 1921–6, and, later, the Ukrainian Cultural and Sports Association Bukovyna (1926–44) and the student Hromada in Iaşi, as well as a student umbrella organization the Union of Ukrainian Student Organizations in Romania.

The number of Ukrainians residing in central Romania grew in 1940, when the Soviet annexation of Bukovyna and Bessarabia sent out waves of refugees. Before the outbreak of the Second World War the Romanian government granted the Ukrainian minority certain cultural rights, and as a result, a Ukrainian radio station (director, Mykola Kovalevsky), newspaper (Zhyttia, edited by I. Havryliuk), and journal (Batava) were established.

During the war the government once again deprived Ukrainians of their rights and began a campaign of terror to speed up assimilation, Romanian colonization, and economic exploitation. All forms of Ukrainian organizational life were proscribed, and concentration camps were built. Ukrainian patriots, such as Olha Huzar and M. Zybachynsky, were subjected to a show trial by a military tribunal in Iaşi on 26 January 1942. Prior to the invasion of Romania by the Soviet Army, some Ukrainians fled to the West, but most stayed behind. With the Soviet occupation, some Ukrainian activists (Ivan Hryhorovych, O. Masykevych, V. Yakubovych, and others) were arrested and deported to the USSR.

The boundaries of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Romanian Socialist Republic established after the Second World War did not coincide with ethnographic territories, and thus small segments of Ukrainian ethnographic territory remain part of the latter. These include southern Bukovyna (50,000 Ukrainians in 32 locales), Dobrudja (40,000 Ukrainians in 23 locales), and the Maramureş region (about 45,000 Ukrainians in 15 locales). There are about 15,000 Ukrainians living in eight villages of the Banat region (some of whom emigrated to the Ukrainian SSR in 1940) and another 15,000 dispersed throughout central Romania. Ukrainians reside also in Baia Mare, Bucharest, Cluj, Constanţa, Iaşi, Lugoj, Ploieşti, Timişoara, Braşov, Tulcea, Suceava, Rădauţi, and other cities. The figures amount to a total of approximately 165,000 Ukrainians in Romania, although the official figure of the 1956 census was only 68,300. The Union of Ukrainians in Romania, however, claimed in 1991 that there were 250,000 Ukrainians living in 142 cities of Romania (preliminary official statistics for 1992 stated there were only 66,800). According to the official 2011 census numbers, 51,007 Ukrainians live in Romania which constitutes 0.27% of the country’s total population.

Under the socialist regime in Romania, no official Ukrainian community organizations existed even though the constitution recognized the rights of national minorities. The attitudes of the Communist party and government to local Ukrainians were variable, but usually negative. Before 1947 they did not even acknowledge the existence of a Ukrainian minority. In 1948–64 Ukrainians were afforded the opportunity for a measure of cultural and educational activity. Nevertheless, an attempt to intimidate the Ukrainian intelligentsia was made at a show trial in 1959, when V. Bilivsky, the editor of a Ukrainian publication, was charged with encouraging readers to read Ukrainian-language materials and maintain their culture, and sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. A similar trial was held in Sighetul Marmaţiei. In 1964 the Romanian government began to close down Ukrainian cultural institutions. The adoption of a new constitution in 1965 once again enshrined minority rights, but it brought no practical gains for Ukrainians. In 1968 Ukrainians were allowed to organize district workers’ councils in the Suceava region and Maramureş region. These were headed by I. Zakhariichuk and Yu. Kaniuka, but achieved little. The policies of Nicolae Ceauşescu’s regime (1965–89) thereafter became increasingly chauvinistic.

Cultural and educational life. The school reform of 1948 enabled the development of Ukrainian-language instruction at the primary, secondary, and postsecondary levels. For the next 10 years there were 120 active primary schools with Ukrainian-language courses (involving about 200 Ukrainian teachers and nearly 10,000 pupils). Ukrainian courses matching the regular school curriculum were conducted in gymnasiums in Seret, Sighetul Marmaţiei, and Suceava (with 77 graduates by 1957), and courses in Ukrainian were also offered in teachers' colleges in Seret, Sighetul Marmaţiei, and Tulcea (with 54 graduates by 1957). Textbooks were written to assist in instruction, including Mykola Pavliuk’s Kurs istorychnoï hramatyky ukraïns’koï movy (Course in the Historical Grammar of the Ukrainian Language, 1964) and Yu. Kokotailo’s Rumuns’ko-ukraïns’kyi slovnyk (Romanian-Ukrainian Dictionary, 1963), with 30,000 entries, and Ukraïns’ko-rumuns’kyi slovnyk (Ukrainian-Romanian Dictionary, 1964), with 35,000 entries.

Various reading rooms, clubs, cultural homes, self-help groups, and youth associations provided cultural amenities in Ukrainian villages. In the cities there were branches of the Asociaţia Romôina pentru legături cu Uniunea Sovietică, the Romanian-Soviet friendship society. In general, however, the level of cultural life remained quite low, with local programs conducted in Ukrainian, Romanian, and Russian. Outside Bucharest no notable folk art ensembles or individual artists existed.

Beginning in the mid-1960s Ukrainian cultural and educational efforts were repressed in both the city and the country. All forms of Ukrainian-language instruction were liquidated, with the exception of the titular existence of the Ukrainian department of the Sighetul Marmaţiei gymnasium and the lectureship in Ukrainian at Bucharest University. Even the use of the Ukrainian forms of place-names in publications was forbidden.

The biweekly Novyi vik appeared in 1949–90, under the editorship of V. Bilivsky and S. Zahorodny until 1959, when they were replaced by M. Bodnia and I. Kolesnyk. Its circulation was initially 10,000 but declined to 4,000 in the 1970s. By that time it consisted largely of Ukrainian translations of Romanian content. The literary-historical bimonthly Kulturnyi poradnyk, edited by V. Bilivsky and V. Fedorovych, was published bimonthly in 1950–8 with a pressrun of 600 to 1,000.

A number of Ukrainians worked in universities and scientific institutes, including I. Robchuk and A. and K. Regush, at the Institute of Linguistics; V. Vynohradnyk (d 1973), at the Pasteur Institute in Bucharest; the Slavists K. Drapaka and I. Lemny; the pedagogue O. Antokhii; the physicist B. Pavliukh, at a polytechnical school in Iaşi; and Vsevolod Karmazyn-Kakovsky, also in Iaşi. In 1952 a department of Ukrainian language and literature was established at the Slavic department of Bucharest University. In 1963–74 the head of the chair of Slavic languages of the Institute of Foreign Languages and Literatures was Mykola Pavliuk, in 1974–83 Mahdalyna Laslo-Kutsiuk, and from 1983 D. Horia-Mazilu and I. Robchuk.

Ukrainian literature is relatively well represented in Romania. In the 1950s Ukrainian writers published their works in Kul’turnyi poradnyk and in the literary supplement to the biweekly Novyi vik. Departments for the publishing of works by representatives of national minorities were set up at the Literaturne Vydavnytstvo (1968–70) and Kryterion publishing houses in Bucharest. The editor of the Ukrainian section was M. Korsiuk. In the 1960s collections of poetry by H. Klempush, O. Melnychuk, D. Onyshchuk, and O. Pavlish were published in Bucharest, as were the novels and short stories of I. Fedko and S. Yatsentiuk. Serpen’ (August, 1964), edited by Y. Myhaichuk, and Lirychni struny (Lyrical Strings, 1968) were literary almanacs. Since 1970 the Romanian Writers’ Union’s Literary Studio of Ukrainian Writers (headed by H. Mandryk) has steered through the publication of collections of verse by M. Balan, I. Fedko, K. Irod, I. Kovach, M. Korsiuk, O. Masykevych, O. Melnychuk, M. Mykhailiuk, I. Nepohoda, Yu. Pavlish, P. Romaniuk, and Stepan Tkachuk. Ivan Reboshapka transcribed and edited folk songs from southern Bukovyna, the Maramureş region, Banat, and Dobrudja, and published the anthologies Narodni spivanky (Folk Songs, 1969), Oi u sadu-vynohradu (In the Vineyard, 1971), and Vidhomony vikiv (The Echoes of the Ages, 1974). Other collections of folk songs include Narod skazhe (The People Will Tell, 1976), Na vysokii polonyni (In the Highlands, 1979), and Oi Dunaiu, Dunaiu (Oh Danube, Danube, 1980). Literary anthologies include Nashi vesny (Our Spring, 1972, prose, edited by M. Mykhailiuk), Pro zemliu i khlib (About Land and Bread, 1972, newspaper reports), Antolohiia ukraïns’koï klasychnoï poeziï (Anthology of Ukrainian Classic Poetry, 1970, edited by Laslo-Kutsiuk), Z knyhy zhyttia: Antolohiia ukraïns’koho klasychnoho opovidannia (From the Book of Life: An Anthology of Classic Ukrainian Short Stories, 1973), and the annual almanac Obriï (est 1979). Mahdalyna Laslo-Kutsiuk published a study of Romanian-Ukrainian literary relations (Relaţiile literare româno-ucrainene în secolul XIX şi la începutul secolului al XX, 1979), a general examination of 20th-century Ukrainian literature under the name Shukannia formy (In Search of Form, 1980), and other literary works. She also edited and published a two-volume collection of Sylvester Yarychevsky’s works (1977–8).

The majority of the Ukrainian population in Romania is Orthodox, although in the Maramureş region and Banat region Greek Catholics are greater in number. After the abolition of the Greek Catholic church in Romania in 1948, its congregation was forced to convert to Orthodoxy, the country’s majority religion. In the 1980s permission was granted for Ukrainians in the Maramureş region to form a Ukrainian Orthodox church, which acts as a distinct jurisdiction within the Romanian Transylvanian eparchy. Liturgies and sermons are almost exclusively (except in Seret) conducted in Romanian, a practice which abets the process of assimilation. The Romanianization of Ukrainians has also proceeded quickly because they are dispersed throughout the country and isolated from other countries with large Ukrainian populations, including Ukraine itself. Also, the intelligentsia has been intimidated to the point that it lives in the cities without any contact with the largely rural population.

After the overthrow of the Ceauşescu regime in 1989, Ukrainian life in Romania began once more to revive. On 29 December 1989 the Union of Ukrainians of Romania was formed and Stepan Tkachuk was elected its first president. The current head of the Union is M. Petretsky. Novyi vik was reconstituted in 1990 as Vil’ne slovo (under the editorship of I. Petretska-Kovach and Yu. Lazarchuk) and began printing articles that were more pertinent to the interests of its readers. In 1997 the Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian Lyceum, the only Ukrainian-language secondary school in Romania (which had been closed down in 1960), was reestablished in Sighetul Marmaţiei.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Iorga, N. Românii de peste Nistru (Iaşi 1918)

Panaitescu, P. L'influence de l'oeuvre de P. Mogila dans les Principautés Roumaines (Paris 1926)

Nistor, I. Problema ucraineană in lumina istoriei (Chernivtsi 1934)

Ciobanu, S. Legăturile culturale româno-ucrainene (Bucharest 1938)

Nistor, I. Ucraina în oglinda cronicelor moldoveneşti (Bucharest 1941–2)

Constantinescu-Iaşi, P. Relaţiile culturale romîno-ruse din trecut (Bucharest 1954)

Tykhonov, Ie. Derzhavnyi lad Rumuns’koï Narodnoï Respubliky (Kyiv 1959)

Studii privind relaţiile romîno-ruse şi romîno-sovietice (Bucharest 1960)

Mokhov, N. O formakh i etapakh moldavsko-ukrainskikh sviazei v XIV–XVIII vv. (Kishinev 1961)

Bezviconi, G. Contribuţii la istoria relaţiilor romîno-ruse (Bucharest 1962)

Ciorănesco, G.; et al. Aspects des relations russo-roumaines. Rétrospective et orientations (Paris 1967)

Marunchak, M. Ukraïntsi v Rumuniï, Chekho-Slovachchyni, Pol’shchi, Iugoslaviï (Winnipeg 1969)

Pavliuk, M.; Robchuk, I. ‘Regional’nyi atlas ukraïns’kykh hovirok Rumuniï,’ Pratsi XII Respublikans’koï diialektolohichnoï narady (Kyiv 1971)

Romanets’, O. Dzherela braterstva. Bohdan P. Khashdeu i skhidnoromans’ko-ukraïns’ki vzaiemyny (Lviv 1971)

Joukovsky, A. Relations culturelles entre l’Ukraine et la Moldavie au XVII-eme siècle (Paris 1973)

Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article was updated in 2011.]

.jpg)