Renaissance

Renaissance. A new age in European civilization that started in Italy in the 14th century and culminated in the 16th century. It was marked by the revival of learning, art, and architecture and by the upsurge of humanism, philosophy, vernacular literature, and printing.

In the visual arts and architecture the term Renaissance refers to the style that replaced the prevailing Gothic style of the Middle Ages. Based on a deliberate return to the art and architecture of classical antiquity, it reached Ukraine in the early 16th century and was popular there until the mid-17th century. It became most widespread in Galicia (particularly in Lviv), where it was introduced by Italian and Swiss architects employed by local magnates, burghers, and church brotherhoods. Its development paralleled that of cities and towns and their expanding political and economic roles.

Some of the earliest examples of the Renaissance style in Ukraine are the Church of the Epiphany in Ostroh (rebuilt in 1521) and the synagogue in Sataniv (1532). In secular architecture its influences can be seen in the application of classical systems of articulation of walls and in the harmonious proportions of the rebuilt castles in Kamianets-Podilskyi (1541–4; photo: Kamianets-Podilskyi castle), Stare Selo (photo: Stare Selo castle) and Olesko in Lviv oblast (photo: Olesko castle), and Berezhany (1554; photo: Berezhany castle) in Ternopil oblast.

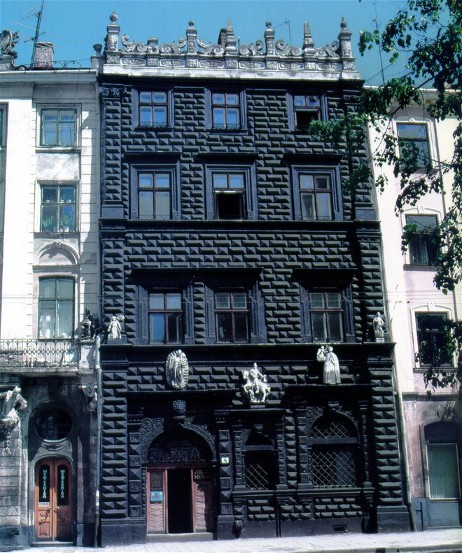

The city of Lviv was reconstructed in the Renaissance style after the fire of 1527. The most interesting examples of surviving Renaissance architecture there are three private residences in Rynok Square: the Hepner building (1540), at no. 28; the Black Building (1577), at no. 4; and the Korniakt building (1580), at no 6. Rusticated stones and pilasters were used in the Black Building; the Korniakt building is a smooth masonry construction with pedimented windows in the upper floors and the only inner-courtyard arcaded loggia in Ukraine. Other examples of Renaissance architecture are the buildings of the Dormition Church in Lviv; the Kampian family chapel, completed in 1619 by Paolo Romanus; the Boim family chapel (1609–11), which has an elaborately carved entablature and a façade profusely decorated with carved ornaments and relief figures that hide the underlying classical structure; and the Roman Catholic Bernardine Church (1600–30), built by Romanus and Amvrosii Prykhylny, which incorporates baroque elements and is thus an example of a transitional building.

The Renaissance had less impact on Ukrainian architecture outside Galicia, because there was little new masonry construction at the time. As old churches were rebuilt, some elements of the late Renaissance were used, but most of these buildings have not survived or were later altered. Saint Elijah's Church (1653) in Subotiv, funded by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, combined the northern Renaissance style with baroque elements.

During the Renaissance sculpture flourished. In Lviv it may be seen in the ornamental and relief carvings of the Black Building, the Korniakt building, and the Kampian and Boim chapels. Their portals and windows are framed with columns and pilasters with elaborately carved plant motifs. The frieze on the exterior walls of the Dormition Church in Lviv has a variety of carved rosettes, sunflowers, grapevines, and figures in the metopes, as does the Kampian Chapel. The façade of the Boim Chapel is covered with relief carvings executed by a group of craftsmen headed by H. Scholtz; it included Jan Pfister, later one of the best-known sculptors in Lviv.

Iconostases were constructed with classical orders and carved plant motifs. The oldest surviving iconostasis, from the Dormition Church in Lviv (1630), is now in the church in Velyki Hrybovychi, Zhovkva raion, Lviv oblast. The iconostasis of the Church of Good Friday in Lviv is another beautiful example of intricate late Renaissance carving in Ukraine.

Memorial tombs were decorated with sculptures of figures in armor reclining or semireclining in traditional Renaissance architectural settings similar to those found in northern Italian tombs. Examples include the tombs of Prince Kostiantyn Ostrozky (1579), at the Kyivan Cave Monastery; of M. Herburt, in the Roman Catholic cathedral in Lviv, by the Nuremberg master P. Labenwolf; of O. Lahodovsky (1573), in Univ (photo: Lahodovsky tomb); of the Sieniawski family (ca 1573–1642), in Berezhany, by Jan Pfister; and of K. Ramultova, in Drohobych.

In book decoration geometric designs gave way to three-dimensional plant motifs. The Peresopnytsia Gospel (1555–61) echoes some aspects of Italian Renaissance ornamentation. The engravings in the Lviv Apostolos (1574), particularly the rendering of the Apostle Luke, are a combination of German Renaissance traditions and Ukrainian-Byzantine influences. In the early 17th century the center of engraving shifted from the presses in Lviv (see Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press) and Ostroh (see Ostroh Press) to the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. It became famous not only for its religious publications but also for its illustrations of historical themes, portraits, and town plans. The gradual shift from Byzantine iconography and stylization to more realistic representation may be seen in the wood engravings in Kasiian Sakovych's book of verses (1622), published on the occasion of the death of Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny.

In painting changes came about gradually. Icons lost some of their flatness and stylization and were painted with more realistic rendering of facial features and with localized landscapes (eg, the icon Transfiguration from Yabluniv, Kosiv raion, Ivano-Frankivsk oblast). In the icon Kiss of Judas from the ‘Passion of Christ’ cycle in the Dormition Church in Lviv, the features of the apostles are individualized, and the figures are more three-dimensional. Portraits of patrons appeared alongside depictions of religious personages (eg, the portrait of Petro Mohyla in the fresco Supplication [1644–6] in the Transfiguration Church in Berestove). Portraits of patrons and their family members without figures of saints came into existence with the rise of rich burghers. In the portrait of the Pochaiv Monastery patron A. Hoiska (ca 1597) the previous static representation and flattened rendering of the figure have given way to a more softly modeled head. Memorial portraits of patrons were usually done on dark backgrounds, and attention was concentrated on the modeling of faces (eg, the portraits of J. Herburt [1578] and Konstiantyn Korniakt [1603]). Secular portraits of the ruling aristocracy and of the rich also gained in popularity. The portraits of K. Zbaraski and K. and O. Korniakt (early 17th century) are full-length formal depictions.

The Renaissance style left its imprint on the furniture of the time and in the decorative arts, particularly in the more realistic rendering of plant motifs. The Easter shroud (1655) from the Kyivan Cave Monastery, with its embroidered silver and gold floral borders, is a fine example of the decorative art of the period.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Miliaieva, L.; Lohvyn, H. Ukraïns’ke mystetstvo XIV–pershoï polovyny XVII st. (Kyiv 1963)

Daria Zelska-Darewych

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)