Proclamation of Ukrainian statehood, 1941

Proclamation of Ukrainian statehood, 1941 (Akt 30-oho chervnia). In the wake of Germany's attack on the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on 22 June 1941, several members of the Bandera faction of the recently split Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN[B]) set out to proclaim a Ukrainian state in Lviv. They put into motion a bold plan to force the German government to commit itself to an independent Ukraine. It was their hope the Germans would take what they perceived to be a rational course of action and ally themselves with the ‘enslaved’ nations of the USSR; alternately, a proclamation of statehood could provide a rallying point for national resistance in the event that Germany should turn against the interests of the Ukrainian people. Their actions have been assessed as brilliant or reckless (even foolish) by supporters of Ukrainian aspirations for independence. The Soviet authorities (especially after regaining control of Western Ukraine) painted them in the blackest terms as the perfidious undertakings of evil collaborators riding on the coattails of the Nazis.

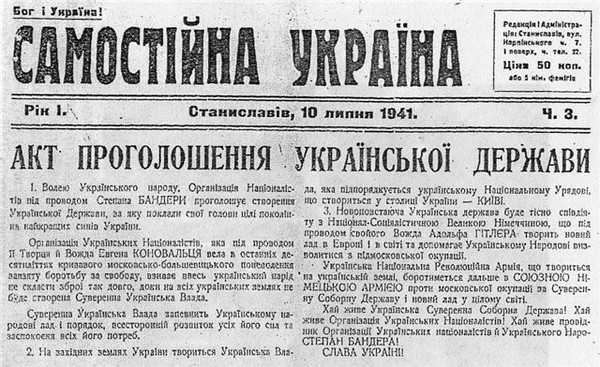

Stepan Bandera's lieutenant, Yarosalv Stetsko, entered Lviv on the same day as the Germans, 30 June 1941, and began the task of state-building. A group of 50 to 200 Lviv residents (estimates vary) came to a hastily arranged evening meeting to hear what the OUN ‘émigrés’ from Cracow had to report, only to witness Stetsko declare: ‘By the will of the Ukrainian people the OUN, under the direction of Stepan Bandera, proclaims the creation of a Ukrainian state.’ What is believed to be the original of several versions of the proclamation went on to say that this Western Ukrainian government would submit to a national government yet to be created (in Kyiv), and that it would co-operate with Germany in its struggle against Moscow's occupation of Ukraine.

The OUN(B) ‘Akt 30-oho chervnia’ (Act of 30 June), as the proclamation has come to be known, was followed by a decree by Stepan Bandera appointing Yaroslav Stetsko as head of state. In that way the OUN(B) executed its plan as a rapid series of what it hoped would become faits accomplis that took both the Germans and the Ukrainians by surprise. That course of action, in fact, was based on a practical consideration, for if the Gestapo had been warned of the possibility, it likely would have stopped the entire affair.

The OUN(B)'s coup was in harnessing a significant, albeit short-lived, legitimacy for its ‘Akt.’ Yarosalv Stetsko could intimate that the foundation for his government had already been laid in Cracow on 22 June 1941 through the OUN(B)'s efforts at consolidating the émigré community in a Ukrainian National Committee (Cracow). The split in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists' ranks did not immediately undermine Stetsko's position, since the Soviet occupation of Galicia had kept Lviv residents largely ignorant of that development. (Ironically, it was the ‘Akt’ itself which attracted attention to the matter by highlighting that there was an OUN under Stepan Bandera; Lviv residents knew only of an OUN under Andrii Melnyk, ie, OUN(M). More important, the evidence suggesting a German-OUN(B) agreement (where there was none) was overwhelming. The OUN(B)'s confident and unprecedented public appearances, the fact that its volunteer unit Nachtigall, dressed in German uniforms, was leading the German army into Lviv, the greetings of a German officer at the proclamation itself, and the OUN's peaceable control of Lviv radio for some three days after the German arrival all contributed to the impression that there was such an agreement. Doubts even among the skeptics dissipated when Stetsko and Nachtigall's chaplain, Ivan Hrynokh, had an audience at the residence of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky and procured his blessing as well as his immense authority for the OUN(B)'s imminent ‘Akt.’ Hrynokh spoke at the proclamation on behalf of the Ukrainian soldiers in Nachtigall and read over Lviv radio Sheptytsky's pastoral letter, which exhorted the nation to support Stetsko's government. The inaction of the German army in establishing a civil administration, and the fact that spontaneously formed Ukrainian administrations were at first tolerated, strengthened the illusion of German approval. Various Ukrainian bodies pledged their allegiance to Stetsko's government, and the proclamation was joyously repeated at mass gatherings all over Western Ukraine.

Stetsko's government was effectively paralyzed when he was quietly ushered to Berlin for ‘discussions’ on 12 July 1941, although public perception did not immediately recognize the significance of the move. Shrewdly, the Germans did not begin their mass arrests of OUN(B) members until mid-September, by which time most of Ukraine had been easily occupied.

During his brief tenure 29-year-old Yaroslav Stetsko controlled no significant forces and was unable to bring in outside (non-OUN[B]) expertise to his administration. Much of the Lviv leadership had denied him their co-operation on three grounds: that the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists first had to mend its internal split; that neither the international nor the internal situation justified the risks of such a proclamation in the absence of knowledge of Germany's plans for Ukraine; and that there was concern about what was perceived as the amorality of OUN(B) behaviour. The last objection was based on false or misleading OUN(B) claims about its relationship with the Germans, about the nature of its consolidation of Ukrainian émigrés, about internal OUN difficulties, and about the consent of Lviv leaders to positions in Stetsko's administration. The OUN(B) quickly lost its credibility, and a non-OUN(B) council to deal with the Germans was formed. Even Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky publicly withdrew his support. In spite of those setbacks and pressure from the Germans, the OUN(B) leadership resisted all demands to revoke the ‘Akt.’ Their resistance was a key element in the subsequent arrest of the OUN(B) leaders by the Nazis, as well as of prominent OUN(M) figures, who themselves had been considering making a proclamation of Ukrainian statehood in Kyiv.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lysyi, V. ‘Do istoriï 30 chervnia,’ Vil’na Ukraïna, no. 11 (1956)

Pankivs’kyi, K. Vid derzavy do komitetu (New York–Toronto 1957)

Rosliak, M. ‘Do istoriï 30 chervnia 1941 r.,’ Vil’na Ukraïna, no. 14 (1957)

Stets’ko, Ia. Trydsiatoho chervnia 1941 (Toronto 1967)

Kosyk, V. L'Allemagne national-socialiste et L'Ukraine (Paris 1986)

Michael Savaryn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]