Prešov region

Prešov region [Пряшівщина; Priashivshchyna]. An area within the northeastern part of Slovakia inhabited by Ukrainians. The region has never had a distinct legal or administrative status, so the term Prešov region—also Prešov Rus'—is encountered only in writings about the area. The name derives from the city of Prešov (Ukrainian: Пряшів; Priashiv), which since the early 19th century has been the religious and cultural center for the region’s Ukrainians. The alternate term, Prešov Rus', reflects the fact that until the second half of the 20th century the East Slavic population there referred to itself exclusively by the historic name Ruthenian (Rusyn), or by its regional variant, Rusnak.

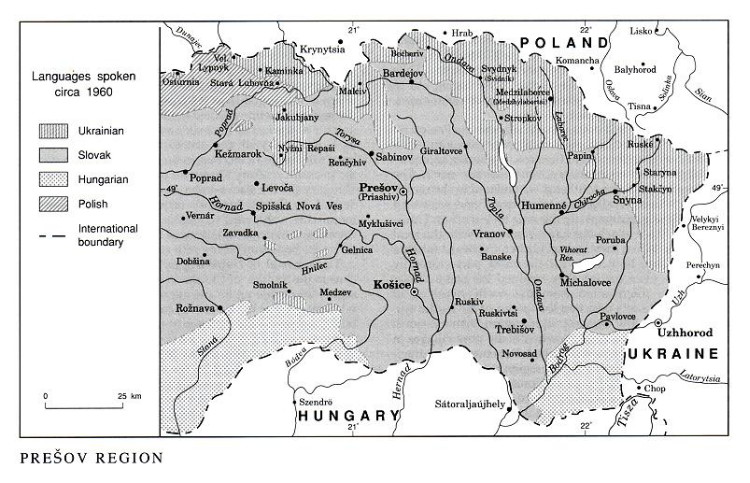

At present the Prešov region is administratively part of Slovakia. The part of Slovakia inhabited by Ukrainians consists of about 300 villages located within the northernmost portions of the counties (Slovak: okresy) of Stará L’ubovňa, Bardejov, Svydnyk (Svidník), Prešov, and, in particular, Humenne. Before 1918 the area made up the northernmost portions of the historical Hungarian komitats (megye) of Spiš (Hungarian: Szepes), Šariš (Sáros), Zemplin (Zemplén komitat), and southwestern Už (Ung). According to official Czechoslovak and Slovak census data Ukrainians form a majority in none of the present-day counties. In 1991, 32,400 inhabitants in the Prešov region designated their national identity as Ruthenian (Rusyn) or Ukrainian, although unofficial sources estimate their number could be as high as 130,000 to 140,000.

The Ukrainians inhabit a small strip of territory that somewhat resembles an irregular triangle bounded by the crests of the Carpathian Mountains in the north. Starting from the west at a point in the valley of the Poprad River, the Prešov region gradually widens in an eastward direction until it reaches as far south as the outskirts of Uzhhorod, near the border with Ukraine.

The Prešov region forms an ethnographic unit with the Lemko region on the adjacent northern slopes of the Carpathian crests. Scholars therefore often refer to the Prešov region as the southern Lemko region. The region’s inhabitants, however, have never, with rare exceptions, designated themselves Lemkos, and their political separation from the north (which eventually fell under Polish control) has allowed them to follow a distinct historical development.

Geography and climate. The Prešov region makes up about 3,500 sq km of territory. It sits in some of the lowest elevations of the Carpathian Mountains within the Lower Beskyd and Western Beskyd ranges; most of the Ukrainian villages are situated only 450–900 m above sea level. The generally low Beskyds (highest elevation 1,289 m) are broken by several passes—Tylych Pass (683 m), Duklia Pass (502 m), Lupkiv Pass (657 m), Ruskyi Pass (797 m)—which historically have played an important role in the movement of people and goods to and from Poland.

Several river valleys connect the region southward into the Slovak lowland and the Hungarian plain. The major rivers, the upper reaches of which flow southward through the Prešov region toward the Tysa River, include (from west to east) the Poprad River (which unlike the others flows northward) and the Hornád River, the Torysa River, the Toplia River, the Laborets River, the Ondava River, and the Chirokha River. The north–south flow of the rivers has until recently made it easier for Ukrainians to reach Slovak-inhabited towns at the southern end of their several valleys than to reach the valleys immediately to the east or west inhabited by their fellow Ukrainians.

The climate is basically continental, although somewhat warmer than in the neighboring Transcarpathia to the east. At lower elevations the temperature averages 21°C (July) to –3°C (January), with an annual rainfall of 580 mm. At higher elevations the temperature averages drop to 14°C (July) and –8°C (January), with rainfall increasing to 1,100 mm annually. The Prešov region today remains an agricultural and pastoral land which, owing to the mountainous and forested terrain, at best affords a subsistence-level economy. Lumbering is the only other viable economic pursuit.

Early history. There is much disagreement concerning the early history of the Prešov region and of the Ukrainians (Ruthenians) living south of the Carpathian Mountains. Archeological evidence suggests that the region was already inhabited during the late Stone Age. From the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD a series of peoples—Celts, Dacians, Goths, Huns, and Avars—passed through, settling there briefly and leaving behind remnants of their way of life. Linguistic and archeological evidence indicates that by the 6th or 7th century AD the region's inhabitants were Slavs, although there is no consensus on whether they were West Slavs (‘ancestors’ of the Slovaks) or East Slavs (White Croatians, ‘ancestors’ of the Ruthenians [Ukrainians]). It seems that the first permanent settlers in the Prešov region arrived from north of the Carpathian Mountains sometime between the 6th and 11th centuries, which date would suggest that they were East Slavs. Slovak scholars contend, however, that there was a continuous settlement of West Slavs from the 7th century, and that the ancestors of the Ukrainian-Ruthenians did not arrive in the area until their migration from Galicia beginning in the 14th century (a view also held by Hungarian scholars). It has also been debated whether the Prešov region received Christianity in the Byzantine form from the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century or from Kyivan Rus’ in the 11th century. What is certain is that the first parishes in the Prešov region, for which there are documents beginning only in the 14th century, were initially under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox bishop of Peremyshl and then (after the 15th century) the bishop of Mukachevo.

Throughout its early history the Prešov region was a sparsely settled border area between the Hungarian Kingdom to the south and the Rus’ Halych principality to the north. In the 11th and 12th centuries the Hungarian kings pushed northward toward the crest of the Carpathians and even beyond, into parts of Galicia, where they ruled intermittently until the end of the 14th century. To ensure their control of that northern border region the Hungarian kings granted, during the 14th century, large tracts of land to princes (mostly from southern Italy and therefore related to Hungary’s new ruling House of Anjou), such as the Drugeth family in Zemplin county (see Zemplén Komitat) and the Perényi family in Šariš county. Thus from the 12th century until 1918 the Prešov region was to remain within the political and socioeconomic framework of the Hungarian Kingdom.

The first consistent documentation about the Prešov region dates from the 14th century, thereby coinciding with the increasing settlement of the area. Ukrainian colonization came from two directions, southeast and north. The colonization from the southeast was related to the movement of Vlachs (Wallachians) northward and westward through the Carpathian Mountains. By the time they reached Transcarpathia, the Wallachians had assimilated with the local population. When they moved farther westward into the Prešov region, they were for the most part ethnically Ukrainians, even though they retained the name Wallachians. The colonization from the north consisted of Ukrainian peasants who fled the spread of the feudal system in Galicia. The heaviest immigration from the north dates from the 16th century, when many new villages in the Prešov region were established. Peasants were attracted to the sparsely settled Prešov region because of the special privileges granted to new colonists, including limited taxes and duties, a certain degree of self-rule and judicial authority over minor crimes, and the right to buy and sell land.

The 16th and 17th centuries. Hungarian control over the Prešov region increased during the 16th century, after Hungary’s Christian princes were forced to retreat to the northern part of the kingdom in the wake of their defeat at Ottoman hands in 1526. As a result the feudal duties required of Ukrainian peasants and Wallachian shepherds increased. The princes themselves were soon embroiled in a dynastic struggle for the Hungarian crown.

The Hungarian rivalries assumed a religious dimension in the second half of the century, when the Reformation pitted Hungarian Protestant princes in Transylvania against Catholic princes in the rest of the non-Ottoman-ruled kingdom. The Orthodox Ukrainians found themselves caught in the middle. The Prešov region came under control of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty, and Transcarpathia, including the Orthodox eparchial see of Mukachevo, came under Protestant Transylvania. The Ukrainians in the Prešov region were now cut off from their brethren just to the east. The situation strengthened their contact northward with the diocese of Peremyshl, from which Orthodox church books, icons, and other religious materials now came in greater numbers. The contact grew after the Church Union of Berestia of 1596, when the Uniate church (Greek Catholic church) came into being in Ukraine. Following that example, Prince G. Drugeth III (d 1620) of Humenne, who owned numerous villages in the Prešov region, tried in 1614 to introduce a church union on his lands. As part of his effort he established the Jesuit College in Humenne (1613), the first secondary school for the Prešov region. Although Drugeth's efforts failed, his desires were realized with the Uzhhorod Union of 1646. Backed by pro-Habsburg Hungarian rule, the union took hold in the Prešov region, and most of the Orthodox Ukrainian villages there became Uniate. Among the exceptions were a few villages that became Protestant (Lutheran and Calvinist). The Protestant presence, however, was short-lived. By the mid-18th century all the Ukrainian villages had become Uniate (later Greek Catholic); they remained so, with few exceptions, until 1918.

Dynastic and religious wars between pro- and anti-Habsburg forces broke out in the wake of the Uzhhorod Union of 1646 and ravaged the Prešov region. The Ukrainians in the region sometimes joined in the military conflicts, most notably in the last of the major anti-Habsburg revolts, led by F. Rákóczi. With the restoration of order (and Habsburg rule) came an increase in the feudal dues imposed on the peasantry. Many Ukrainian peasants fled to southern Hungary (in the Bačka-Vojvodina region of present-day Serbia), to Slovak territory farther west, or across the mountains northward to Galicia. In Šariš and Zemplin counties (see Zemplén komitat) as many as one-third of the villages were deserted by the beginning of the 18th century.

The renewal of Habsburg authority. The marked decline in the number of Ukrainian inhabitants in the Prešov region was made up for during the 18th century by natural demographic increases that resulted from political stability and economic prosperity under Habsburg rule as well as new immigration from Galicia, especially after the 1730s. Since local Hungarian landlords were anxious to repopulate their villages in the Prešov region, they welcomed the newcomers with reduced taxes and other temporary privileges. The period also saw an influx of Galician Jews, who were often contracted by the lords to collect rents, tolls, and other duties and granted the right to brew and sell liquor.

The 18th century also witnessed an improvement in the status of the Uniate clergy following an imperial decree of 1692 that had freed them from all duties previously owed to local landlords. Before long the priests themselves became village landlords.

The prosperity of the 18th century encouraged significant cultural development. Numerous churches were constructed throughout the Prešov region; those built entirely of wood still represent some of the finest achievements of Ukrainian church architecture. The first publications for Ukrainians also date from the period, including the Bukvar (Primer, 1770) attributed to Bishop Ivan Bradach. Elementary schools were established at the rural monasteries of Bukovská Hôrka and Krásny Brod, the latter including an advanced philosophical and theological school, where monks such as A. Kotsak prepared grammars and other texts that in part used the local Ukrainian (Ruthenian) vernacular. The second half of the 18th century also saw the appearance of the first histories of Ukrainians, the most extensive being a three-volume work by Yoanykii Bazylovych, a native of the Prešov region.

In 1771, under Bishop Bradach, the Habsburgs granted the Mukachevo eparchy equal status with the Roman Catholic church and accepted a change in the name of the church from Uniate to Greek Catholic. In 1787 the Mukachevo eparchy established a vicariate for Greek Catholics in the Prešov region with a seat in Košice (in 1805 it was transferred to Prešov). Finally, in 1815 an Austrian imperial decree, confirmed three years later by the Apostolic See, raised the Prešov vicariate to the status of an independent eparchy. The new eparchy under its first bishop, Hryhorii Tarkovych, consisted of 193 parishes, with 149,000 faithful. With the creation of the eparchy Ukrainians in the Prešov region were for the first time made jurisdictionally distinct from their brethren just to the east in Transcarpathia, who remained within the Mukachevo eparchy. That development also brought about the rise of Prešov as the region's cultural center and the establishment of an eparchial library, a cathedral church, an episcopal residence, and, eventually, a seminary (1880) and teacher's college (1895).

The Greek Catholic church remained the only choice for Ukrainians of the Prešov region who wished to pursue a career other than agriculture. For those few who obtained an education but wished to enter secular professions without having to become assimilated to the increasingly dominant Hungarian culture of the kingdom in which they lived, one possibility was emigration abroad. By the beginning of the 19th century Ukrainians had begun to emigrate eastward from the Prešov region, some to neighboring Galicia, but most to the Russian Empire, where they were to become leading figures in the recently reformed tsarist educational system—Mykhailo Baluhiansky, Petro Lodii, and Ivan Orlai. Only Orlai continued to maintain contact with his homeland. He published a history of the Carpatho-Ruthenians (1804), which contended that Hungary's ‘Russians’ were related to other ‘Russians,’ especially those living in Little Russia (Ukraine).

The socioeconomic structure in the Prešov region changed little during the first half of the 19th century. Nor did the national consciousness of the Ukrainians in the region (and in Transcarpathia) manifest itself in the same manner as among their Slavic neighbors during what was a general period of national awakening. They had no newspapers, no cultural organizations, and no standard language. Their secular intelligentsia emigrated abroad (mostly to the Russian Empire), and the few Greek Catholic clergymen who thought in national terms expressed at best vague ideas of unity with Russia. Most, nevertheless, adapted to the new conditions in Hungary, where a vibrant Hungarian national movement called upon all its citizens—of whatever ethnolinguistic background—to learn Magyar and to adopt it as the cultured medium for communication. That state of affairs made the growth of Ukrainian national life that began with the Revolution of 1848–9 in the Habsburg monarchy all the more remarkable.

The national awakening and decline. With the outbreak of the Revolution of 1848–9 in the Habsburg monarchy the Greek Catholic clergy and seminarians in the Prešov region immediately expressed support for Hungary. In sharp contrast to them, the secular leader Adolf Dobriansky formulated a political program calling for the unity of Ukrainians in Hungary with their brethren north of the mountains in Galicia. He then played an important role in the suppression of the Hungarian revolt as Austrian liaison with the Russian army, which Tsar Nicholas I sent in response to Vienna's request for aid. After Hungary was defeated in August 1849, the kingdom was reorganized under direct Austrian military control. Dobriansky became administrator of the Uzhhorod civil district (Uzh, Bereg [Berehove], Ugocsa, and Maramureş counties), where he implemented policies for Ukrainian national autonomy. Ukrainians in the Prešov region demanded to be united with the ‘Rusyn’ Uzhhorod district, but that ambition was not realized before the district was abolished in March 1850.

More lasting than political gains were the cultural achievements of the Ukrainians of Hungary. Again, they were associated with an activist from the Prešov region, the Greek Catholic priest Oleksander Dukhnovych. In 1850 he organized the first Ukrainian cultural organization in the region, the Prešov Literary Society. In 1862 he worked with Dobriansky to establish the Society of Saint John the Baptist in Prešov, whose purpose was to educate young people in a national spirit. Dukhnovych also wrote several histories of his people and newspaper accounts of their current affairs.

Despite the achievements of Adolf Dobriansky and Oleksander Dukhnovych in stimulating the political and cultural renaissance of their people, the majority of the Greek Catholic clergy and young seminarians remained immune to the Slavic aspects of their culture. They preferred to speak Magyar, to adopt Magyar mannerisms, and to strive to be loyal citizens of Hungary—even at the expense of surrendering their national identity.

The political changes that resulted from the 1867 Ausgleich that created the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy (Austro-Hungarian Empire) had a profound effect on Ukrainian life in the Prešov region. The Magyars now had full control over all national minorities living in Hungary, including (1870) approximately 450,000 Ukrainians (18 percent of whom lived in the Prešov region). Magyarone Ukrainians had little difficulty in adjusting to the new situation. Oleksander Dukhnovych and his generation, however, were now in a more tenuous position. Their situation was exacerbated by the fact that they had never resolved the question of a standard literary language (often resorting to a jargonish yazychiie viewed as superior to the ‘peasant vulgarism’ of vernacular speech) and the closely related problem of national identity. Increasingly they began to identify with the Russian nationality as a way of preventing the disappearance of their people and became Russophiles.

By the 1870s no Ukrainian institutions or publications remained in the Prešov region. Literary production continued, although local writers were forced to work in isolation and to publish whenever possible in Uzhhorod or in Lviv in neighboring Galicia. Of the best-known Ukrainian writers in Hungary of that period four were natives of the Prešov region: Oleksander Pavlovych, Anatol Kralytsky, Yulii Stavrovsky-Popradov, and I. Danylovych-Korytniansky. All were Greek Catholic priests, who through their poetry, prose, and plays tried to instill pride and patriotism by describing the physical beauties of their Carpathian Mountains homeland and the supposed greatness of its historical past. Their message, however, was for the most part not in the vernacular speech of the local populace, but in the yazychiie.

More problematic for the survival of Ukrainians was the fact that the educational system was not producing any new cadres of leaders with some form of national consciousness. The few secondary schools in Prešov were administered by the Greek Catholic church, and all taught exclusively in Magyar. At the lower level there were elementary schools sponsored by the church, village, or state, where students received at least rudimentary training in the Cyrillic alphabet and therefore some exposure to their native culture. That situation was to change rapidly, however. In 1874 the Prešov region had 237 elementary schools using some form of the Ukrainian language; three decades later, in 1906, that number had decreased to only 23, with 68 more offering Ukrainian-Magyar bilingual instruction.

Those decades saw the economic situation of the Prešov region decline substantially, as farm holdings diminished in size owing to a growing population, and the need for agricultural laborers decreased owing to mechanization. Those factors forced Ukrainians to emigrate, in particular to the United States. The first few individuals left in the late 1870s, and by 1914 an estimated 150,000 Ukrainians had left Hungary, approximately half of them from the Prešov region. The departing emigrants not only helped to relieve the immediate pressures on the local economy but also contributed to it by means of the remittances they forwarded from the New World. Some later returned home to buy up as much land as possible.

The Hungarian authorities maintained and intensified their policy of Magyarization in the early 20th century. All Greek Catholics were now considered ‘Magyars of the Greek Catholic faith,’ and people were compelled to Magyarize their family and given names. A new school law took effect in 1907, as a result of which the 68 Magyar-Ukrainian bilingual schools in the Prešov region were fully Magyarized by 1912, and the number of schools using some form of Ukrainian declined from 23 to 9. The government's policy was more often than not implemented by local Magyarone teachers, priests, and officials of Ukrainian background. Foremost in such efforts was the Magyarone Greek Catholic bishop of the Prešov eparchy, I. Novak, who in 1915 introduced the Latin alphabet into school and liturgical texts and dropped the traditional Julian calendar in favor of the Gregorian.

At the time of the First World War Ukrainian national life in the Prešov region had reached its lowest point. There were no secondary schools and only a few elementary schools where the native language was used; there were no national institutions, and the only publication was a weekly (Nase otecsesctvo, 1916–19) written in a Magyar-based Latin alphabet and devoid of Ukrainian patriotism. Finally, the hierarchy and many priests in the Greek Catholic church, as well as the secular and lay intelligentsia, had been completely Magyarized.

The impact of the First World War. In the months immediately following the end of the Firts World War the implications of the contemporary political upheavals for Ukrainians living south of the Carpathian Mountains were unclear. The first movement toward change came from Ruthenian immigrants living in the United States. Under the leadership of a young Ruthenian-American lawyer, Hryhorii Zhatkovych, the American National Council of Uhro-Rusins was established in the summer of 1918. By the end of the year its members were actively pursuing efforts to incorporate their European homeland into the new Czechoslovakian state as an autonomous region. Meanwhile Ukrainians in the Transcarpathian region began holding a series of meetings (councils) to discuss their political future. The first was the Ruthenian People's Council in L’ubovňa, held on 8 November 1918. The gathering concluded that continued life under Hungary was unacceptable, but it could reach no consensus on an alternative. When a group of Ukrainians met in Uzhhorod on 9 November 1918 and pledged their loyalty to Hungary, the Ruthenian People's Council reconvened in Prešov. Several months of contradictory political activity followed: national councils were convened farther east in Transcarpathia, and called for union with Ukraine; the Hungarian government (republican and communist) attempted to restore its rule in the area; and the Carpatho-Ruthenian–American delegation arrived with its proposal for union with Czechoslovakia. The developments culminated on 8 May 1919, when some 200 Ukrainian delegates met in Uzhhorod to form the Central Ruthenian People's Council. The council unequivocally endorsed the option of autonomy within a Czecho-Slovak state, albeit at the cost of dropping plans for union with the Lemkos to the north.

The establishment of the territory of Subcarpathian Ruthenia (Czech: Podkarpatská Rus) created a ‘temporary’ boundary along the Uzh River, which left Ukrainians of the Prešov region separated administratively from their brethren farther east for the first time. Within a decade the boundary, with slight changes, became permanent. The Prešov region remained outside Subcarpathian Ruthenia and under Slovak administration.

The interwar years. Ukrainian life in Czechoslovakia experienced a notable renaissance during the interwar era. The Hungarian authorities had had an active policy of assimilation but the Slavic state was generally sympathetic to the Ukrainians’ language and culture. The situation did not entirely hold for the Ukrainians of the Prešov region, however, for whereas their kinfolk in Subcarpathian Ruthenia were established as one of the state nationalities, in the Prešov region they constituted only a national minority with no political or administrative autonomy.

The political status of the Prešov region remained uncertain until 1928. All Ukrainian leaders had maintained from the earliest negotiations with Czechoslovak leaders in the United States and Europe that the Ukrainian-inhabited Prešov region would have to become part of an autonomous Subcarpathian Ruthenia. Slovak leaders, however, remained completely opposed. The question of unification with their brethren to the east became the basic goal of the Russophile Ruthenian People's party, established in 1921 in Prešov by the brothers Konstantyn, Nikola, and Antin Beskyd. The matter was finally resolved in 1928, when the national parliament passed a law dividing the Czechoslovak Republic into four provinces (Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia) and making permanent with only slight changes the formerly temporary boundary between Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia. Despite that decision the Ruthenian People's party and its organs, Rus’ (Prešov 1921–3) and Narodnaia gazeta (Prešov 1924–36), continued in vain to demand unification.

Separated from Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the Ukrainians of the Prešov region were subject to the policies of a Slovak administration unsympathetic to them. The Slovakization of the school system began in 1922, when the minister of education in Bratislava adopted a policy whereby Greek Catholic elementary schools that had taught in Magyar before 1919 should now use Slovak. In spite of guarantees in the Czechoslovak constitution that (theoretically) required at least 237 elementary schools to provide Ruthenian-Ukrainian vernacular instruction, only 95 elementary schools in the Prešov region were doing so in 1923–4. Slovak authorities defended that state of affairs by citing census statistics. But the statistics had been manipulated by local officials who had urged Ruthenian Ukrainians to identify themselves as ‘Czechoslovaks’ on census questionnaires and thereby caused a drop in the number of Ukrainians officially noted as such, from 111,280 (1910) to 85,628 (1921). The resulting census dispute added to the friction between Slovaks and Ukrainians that continued to grow (especially among political leaders) throughout the interwar period.

The economic situation of the Ukrainian population deteriorated as well. Eastern Slovakia, particularly the Prešov region, remained one of the most underdeveloped sections of Czechoslovakia. Lumber mills in about a dozen locations (the largest being Medzilaborce and Udavské) employed only approximately 3.3 percent of the work force in 1930. The vast majority of the Ukrainians (89.6 percent in 1939) remained agriculturalists. Their already precarious situation worsened in the 1930s as a result of a bad harvest in 1931–2, coupled with the Depression. The ensuing bankruptcies and foreclosures prompted several significant disturbances and strengthened the support of antigovernment political parties.

Despite serious political and economic problems there were notable social and cultural developments in the Prešov region during the period. Continued protests by the Ruthenian People's party and the Greek Catholic Prešov eparchy resulted in an increase in the number of schools teaching in some variant of the local dialect of Ukrainian, so that by 1938 there were a total of 168 of such elementary schools and 43 others in which some Ruthenian-Ukrainian was taught. A gymnasium (albeit Russian-language) was opened in Prešov in 1936.

The Orthodox church began making greater inroads in the region during the interwar era. Pro-Orthodox sentiment had arisen in the area for the first time in centuries in the 1890s, as an outgrowth of Russophile tendencies and a response to tsarist propaganda and the return of emigrants from the United States (who had converted during their sojourn abroad). It had been kept in check, however, by the Hungarian authorities. Now, from a base in the village of Ladomirová, near Svydnyk, the church grew to include 18 parishes, with more than 9,000 adherents, by 1935. The initial success of the Orthodox movement was in part related to a crisis in the Greek Catholic Prešov eparchy resulting from the earlier Magyarone sympathies of Bishop Novak and other church hierarchs. The growing shift of Greek Catholics to Orthodoxy was stemmed somewhat by Bishop Dionisii Niaradi, the church's apostolic administrator in 1922–7. The situation of the Greek Catholic church finally stabilized with the appointment of a new bishop, Pavlo Petro Goidych, who provided the active leadership needed to revive it.

The greater freedom of Ukrainians under Czechoslovak than under Hungarian rule made possible a broader discussion concerning national identity. The residents of the region, having had no experience comparable to the blossoming of Ukrainian civic culture in Galicia during the 19th century or to the cathartic Revolution of 1917 in central Ukraine, largely rejected a Ukrainophile orientation. The local intelligentsia urged the people instead to identify themselves as Ruthenians (Rusyny or Rusyns). Characteristically that orientation was manifested in one of two forms, Russian or regional, although it was often difficult to distinguish between the two, as both groups claimed they were Carpatho-Ruthenians (karpatorusskii) maintaining the tradition of 19th-century leaders such as Oleksander Dukhnovych and Adolf Dobriansky. The Russophiles were initially represented by Antin Beskyd and his supporters in the Ruthenian People's party, who demanded the introduction of the Russian language into local schools and touted the notion of one ‘Russian’ people ‘from the Poprad River to the Pacific Ocean.’ The regional Ruthenian orientation was represented by the Greek Catholic hierarchy and by the Prešov branch of the Dukhnovych Society. Their views commonly appeared in the unofficial organ of the Greek Catholic eparchy, Russkoe slovo (Prešov) (1924–38). They were marked by a strong attachment to local culture and institutions as well as to the language used in the area, one of the Transcarpathian dialects that they regarded virtually as a separate Subcarpathian Ruthenian language.

In 1930 Dionisii Zubrytsky and Iryna Nevytska set up in Prešov a branch of the Ukrainianophile Prosvita society, which was also based in Uzhhorod. The group published a few issues of a Ukrainian-language newspaper, Slovo naroda (Prešov 1931–2), but failed to develop a broad network of village affiliates.

A modest renaissance in literature also took place in the Prešov region during the interwar years. The older generation, best represented by I. Kyzak, was joined by new writers, such as Iryna Nevytska, Dionisii Zubrytsky, Fedir Lazoryk, A. Farynych, and M. Horniak. Several other natives of the Prešov region, such as the poet Sevastiian-Stepan Sabol and the playwright P. Fedor, lived and published in nearby Subcarpathian Ruthenia. Among the most prolific scholars at the time was Nikola Beskyd. With the exception of Nevytska, Zubrytsky, and Sabol, most other representatives of the intelligentsia of the Prešov region wrote in Russian and for the most part supported a Russophile national orientation.

The decade of international crises, 1938–48. Following the signing of the Munich Agreement in September 1938 the state of Czechoslovakia was redrawn and transformed into a federal republic. As a result both Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia received their long-awaited autonomy. In October the Ukrainians of the Prešov region, now living in an autonomous Slovakia, formed a national council led by parliamentary deputies I. Pieshchak and P. Zhydovsky. The council called for greater autonomy for the Prešov region and its eventual incorporation into Subcarpathian Ruthenia. The Subcarpathian autonomous government in Uzhhorod included Pieshchak as a state secretary representing the Prešov region.

In early November the Ukrainophile Avhustyn Voloshyn became head of the government of Carpatho-Ukraine. Voloshyn's government demanded union with the Prešov region, but the local population and their predominantly Russophile leaders now rejected association with what they considered an alien ‘Ukrainian’ government. On 22 November the national council in Prešov voted against unification with Carpatho-Ukraine. Instead it urged participation in the December elections to the Slovak Diet. The issue of unification soon proved a moot point. On 15 March 1939 Adolf Hitler made Bohemia and Moravia protectorates of the Third Reich, Slovakia became an independent state allied to Germany, and Hungary forcibly annexed Carpatho-Ukraine as well as a section of eastern Slovakia that included 36 Ukrainian villages (20,000 people) from the Prešov region.

For the duration of the Second World War most of the Prešov region was under the control of a state governed by Slovaks in Bratislava. The government aimed to Slovakize all aspects of the country and targeted the Ukrainians of the Prešov region, since immediately after the Munich crisis they had expressed a desire to unite with Subcarpathian Ruthenia. The national council was banned, and the activity of the Dukhnovych Society restricted. Ukrainians were allowed three deputies to the Slovak Diet, and they were expected to support the government's policy. One newspaper was permitted to operate. Only the Greek Catholic church under Bishop Pavlo Petro Goidych was able to defend the national interests of the Prešov region’s Ukrainians; he did so particularly by assuming responsibility for teaching in elementary schools.

The Ukrainians were among the first in Slovakia to organize an underground resistance, the Carpatho-Ruthenian Autonomous Union for National Liberation (Karpatorusskii Avtonomnyi Soiuz Natsionalnogo Osvobozhdeniia, or KRASNO). They also received assurances from the underground Slovak National Council that the restored state would be ‘a fraternal republic of three equal nations’—Czechs, Slovaks, and Carpatho-Ruthenians. Almost immediately after the withdrawal of German troops village and town councils were formed throughout the Prešov region. On 1 March 1945 their representatives met in Prešov to form the Ukrainian People's Council of the Prešov Region. That was the first time that the name Ukrainian had been used in the title of an organization in the Prešov region. The People's Council also reiterated the long-standing desire for unification with their Transcarpathian brethren, who had been calling for ‘unification with the Soviet Union’ since November 1944. That decision worried the Slovak leaders, who urged Ukrainians in the Prešov region to remain within Czechoslovakia. To that end they guaranteed full rights for the Prešov region Ukrainians as a national minority. By May 1945 the Prešov council finally declared its intention to support the new Czechoslovak government headed by the pre-1938 president, Edvard Beneš, but only on the condition that political and cultural autonomy be granted. On 26 June 1945 the area of Transcarpathian Ukraine became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Ukrainians of the Prešov region were left territorially divided from their Transcarpathian brethren.

According to an agreement on population transfers signed in July 1946 between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, Prešov region Ukrainians were given a chance to emigrate to the Ukrainian SSR if they wished to. More than 8,000 local Ukrainians did so, largely for economic reasons. They settled mainly near Rivne in lands abandoned by Volhynian Czechs who had gone to Bohemia.

The Communist party emerged as the strongest political group in postwar Czechoslovakia. In the Prešov region the Communists obtained 45.9 percent of the vote in the open elections of 1946. Communists also dominated the Ukrainian People's Council of the Prešov Region, which continued to demand that it be recognized as a political body representing Ukrainians. The demand was rejected by the Slovak National Council in 1947, and the rejection highlighted the fact that Ukrainians would have no special autonomous or corporate political status in the restored Czechoslovak republic. The People's Council was more successful in matters of culture: it sponsored the Ukrainian National Theater, a publishing house, an office for schools, a youth organization, and the influential newspaper Priashevshchina (1945–52). In spite of the People's Council's Ukrainian name, much of its business was conducted in Russian.

1948 to 1968. In 1948 the plurality of Czech political life was replaced by communist domination. Major political and social transformations were then undertaken, three of which were to have a profound impact on the Ukrainians in the Prešov region: collectivization, de-Catholicization, and Ukrainianization. Those occurred more or less simultaneously between 1949 and 1953. By 1960 an average of only 63 percent of the farmland in the Prešov region was collectivized. The process of de-Catholicization went much more quickly. The Greek Catholic church was liquidated at a church council in Prešov on 28 April 1950, and all 239 former Greek Catholic parishes, as well as 20 Orthodox parishes, were reorganized into the Orthodox eparchies of Prešov and Michalovce within the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox church. In November 1951 the two Prešov region eparchies became part of the newly created Autocephalous Orthodox church of Czechoslovakia.

The question of national identity was also settled by administrative fiat. Following the Soviet model in Transcarpathia, the regime decided to promote a Ukrainian identity and cultural orientation. Standard Ukrainian was introduced in schools as a subject in 1949. In June 1952 the Slovak Communist party in Bratislava decreed that Ukrainian should be used in all schools of the Prešov region, and the following year it became the language of instruction for all subjects. The local Russophile intelligentsia were compelled to Ukrainianize or lose their positions, and the local population was expected to identify itself as Ukrainian. Most of the new postwar organizations, whether or not they were Russophile in orientation, were liquidated between 1949 and 1952, including the Ukrainian People's Council of the Prešov Region.

In 1951 a new nonpolitical and acceptably socialist organization was created, the Cultural Association of Ukrainian Workers (KSUT). It became the dominant representative association for Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia, until it was succeeded in 1990 by the Union of Ruthenian-Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia. The KSUT sponsored a variety of publications, organized lectures throughout the Prešov region, supported (by 1963) 242 local folk ensembles, and sponsored annual drama, sport, and folk festivals, the largest of which has been held annually since 1956 in Svydnyk. The Czechoslovak government also provided funds to establish the Svydnyk Museum of Ukrainian Culture (1956), a department of Ukrainian language and literature at Šafárik University in Prešov, and the Duklia Ukrainian Folk Ensemble as part of the Ukrainian National Theater in Prešov.

While the Prešov region’s Russophile intelligentsia was adjusting to the new cultural order, some Ukrainian activists from the Ukrainian Transcarpathia, such as Ivan Hryts-Duda and Vasyl Grendzha-Donsky, helped to fill the gap. Also of importance were Ukrainian scholars from Prague, among them Ivan Pankevych, Ivan Zilynsky, and Orest Zilynsky. Former Russophiles from Subcarpathian Ruthenia who were active in the Prešov region’s cultural organizations included Fedir Ivanchov, Yurii Kostiuk, O. Liubymov, and Olena Rudlovchak. Several younger Prešov region intellectuals were sent to Kyiv to supplement their Ukrainian education. Since the 1960s the Prešov region has had a growing number of talented native-born Ukrainian leaders. They include belletrists and publicists, such as Yurii Bacha, Vasyl Datsei, Stepan Hostyniak, Fedir Lazoryk, Ivan Matsynsky, Mykhailo Shmaida, and Vasyl Zozuliak; the theatrical director I. Ivancho; and scholars, such as the linguists P. Bunganych, Vasyl Latta, Mykola Shtets, the literary historians Fedir Kovach and A. Shlepetsky, the historians I. Baitsura, A. Kovach, M. Rychalka, O. Stavrovsky, and I. Vanat, the ethnographers Mykola Mushynka and M. Hyriak, and the musicologist Yu. Tsymbora.

Despite the continued and substantial funding by the Czechoslovak government for the cultural development of the Ukrainian minority, considerable assimilation (to the Slovak nationality) has taken place. Some scholars believe the assimilation is the result of the local population's unwillingness to accept a Ukrainian identity seemingly imposed upon it by external forces. The response is most graphically revealed in the census figures (Prešov inhabitants were asked to identify themselves as Rusnak/Russian/Rusyn/Ukrainian or Hungarian/Czech/Slovak) and school statistics. The census data reveal a decline in the number of people who identify themselves as Ukrainians in the 20th century despite a natural increase in their numbers (from 88,010 in 1880 to 111,280 in 1910 and 37,179 in 1980).

The number of schools teaching Ukrainian (including the regional Transcarpathian dialect) declined during the period 1948–66 from 275 to 68 elementary schools, from 41 to 3 municipal schools, and from 4 to 1 gymnasiums. In many cases Slovak instruction replaced Ukrainian.

The Prague Spring and after. During the political thaw under the regime of A. Dubček, Ukrainians began raising the issue of their status within the country. In March 1968 the Cultural Association of Ukrainian Workers called for a national congress to reconstitute the Ukrainian People's Council of the Prešov Region, and the newspaper Nove zhyttia burst forth with a series of articles demanding political, economic, and cultural autonomy for Ukrainians. The discussion regarding territorial autonomy for the Prešov region that was raised in the debate, however, overstepped the bounds that the Party would tolerate, and the proposed national congress was abruptly called off by the authorities. Greater success was realized in religious affairs when the Greek Catholic church was again legalized, in June 1968. It failed, however, to assume its historic role as a unifying force for Ukrainian interests when it became embroiled in disputes with the Orthodox church over property division and with the church's Slovak clergy over language and leadership issues. Other demands centered on the old question of national identity. Meetings, letters, and newspaper articles reflected a popular desire to do away with the ‘artificial’ Ukrainian orientation of the ‘little band of intellectuals’ and return to ‘our own’ schools and cultural leaders. The people were once again officially referred to as Ruthenians—which term had been forbidden since the introduction of Ukrainianization in 1952—and the proposed national council was to be called the Council of Czechoslovak Ruthenians (Rada Chekhoslovatskykh Rusyniv).

The discussions and plans for change were cut short on 21 August 1968 when the invasion of more than half a million Warsaw Pact troops led by the USSR put an end to the Prague Spring. The shock of external intervention was compounded for Ukrainians of the Prešov region by the protracted Catholic-Orthodox religious struggle and an increasingly hostile attitude toward them on the part of the Slovaks, who were openly critical of their political and cultural demands and even accused Ukrainians of collaboration with the Soviets. (See Slovak-Ukrainian relations in the Prešov region.)

In those circumstances Ukrainian villagers often tried to demonstrate their loyalty by demanding Slovak schools. By 1970 there was only one elementary school using Ukrainian exclusively and 29 with some degree of instruction. That year only 42,146 (out of a potential 130,000 to 140,000) Ukrainians identified themselves as such in the census, in spite of a campaign to do so by the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Beginning in 1970 a policy of ‘political consolidation’ removed supporters of the Prague Spring from the Communist party. Many also lost their jobs, among them the more vocal leaders in the Prešov region. Supporters were also expelled from the Ukrainian Writers' Union and forbidden to publish for periods of time that in some cases lasted two decades. Nonetheless, belletristic and scholarly books and serial publications continued to appear, and Ukrainian cultural institutions, such as Cultural Association of Ukrainian Workers, the Svydnyk Museum of Ukrainian Culture, and the university department in Prešov, maintained about the same level of activity with even greater financial backing than they had before 1968.

Since the Second World War there have been substantial socioeconomic developments in the Prešov region, with the establishment of a communications system, the building of new roads, and the setting up of several industrial enterprises. The development has drastically changed the region's social structure. By 1970 only 30.1 percent of Ukrainians were engaged in agriculture and forestry, and another 24.3 percent in nonindustrial pursuits (probably related to agriculture) whereas 27 percent worked in industry, 9.9 percent in the building trades, 4.5 percent in stores and restaurants, and 2.9 percent in transport. In spite of such improvements the average income of Ukrainians in 1968 was almost three-fifths of the all-Czechoslovak average. The discrepancy has spurred many young people to emigrate to Slovak cities in the eastern part of the country, or westward to the industrial regions of northern Moravia, where wages were much higher; their migration has caused labor shortages on the farms and turned many Ukrainian villages into little more than havens for older people.

That state of affairs has raised some questions about the future of Ukrainians in the Prešov region as a group. For many years assimilation was staved off by the area's economic backwardness and geographic isolation. Social and economic mobility has now altered the physical base of Ukrainian life and increasingly brought younger Ukrainians into the mainstream of a largely Slovak world. Slovakization is further facilitated by the advent of television that is exclusively in Czech or Slovak, the similarity in language and religion between the two groups, and increasing interethnic marriage in which Slovak becomes the dominant medium of the household.

Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution of November 1989 profoundly changed life throughout the country, including the Prešov region. Communist rule came to an end and pluralism was rapidly implemented in political, cultural, religious, and economic affairs. Since that time the Ukrainian intelligentsia of the Prešov region has split into two factions, each with its own organization and publications. Those who eschew the name Ukrainian and insist on calling themselves by the historical name Ruthenians (Rusyns) formed the Ruthenian Renaissance Society (Rusynska Obroda) in March 1990. It began publishing its own newspaper (Narodny novynky) and magazine (Rusyn) using the local Ruthenian dialect of Ukrainian. Together with the newly created World Congress of Ruthenians (established in March 1991) it promotes the idea that the population of the Prešov region together with that of the neighboring Lemko region and Transcarpathia comprise a ‘distinct fourth’ East Slavic nationality. The Oleksander Dukhnovych Theater (formerly the Prešov Ukrainian National Theater) has joined the Ruthenian Renaissance Society's orientation and now stages plays in the local dialect of the Ukrainian language. The Union of Ruthenian-Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia (SRUCH), since February 1990 the successor of the Cultural Association of Ukrainian Workers, later renamed the Union of Ruthenian-Ukrainians of the Slovak Republic, continues to publish in Ukrainian and to favor a Ukrainian self-identification and closer ties with the newly independent Ukraine. The factiousness which effectively splits the Ukrainian minority in the Prešov region has been recognized and supported since 1990 by the Czecho-Slovak federal government and, after the break-up of Czhechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, by the Slovak government as well.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hnatiuk, V. ‘Slovaky chy rusyny? Prychynok do vyiasnennia sporu pro natsionalnist' zakhidnykh rusyniv,’ ZNTSh, 42 (1900)

Húsek, J. Národopisná hranice mezi Slováky a Karpatorusy (Bratislava 1925)

Halaga, O. R. Slovanské osídlenie Potisia a východoslovenskí gréckokatolíci (Košice 1947)

Shlepetskii, A. (ed). Priashevshchina: Istoriko-literaturnyi sbornik (Prague 1948)

Haraksim, L. K sociálnym a kúlturnym dejinám Ukrajincov na Slovensku do roku 1867 (Bratislava 1961)

Varsik, B. Osídlenie košickej kotliny, 3 vols (Bratislava 1964–77)

Bajcura, I. Ukrajinská otázka v ČSSR (Košice 1967)

Stavrovs’kyi, O. Slovats’ko-pol'sko-ukraïns'ke prykordonnia do 18-ho stolittia (Bratislava–Prešov 1967)

Kubinyi, J. The History of Prjašiv Eparchy (Rome 1970)

Vanat, I. Narysy novitnoï istoriï ukraïntsiv Skhidnoï Slovachchyny, 2 vols (Bratislava–Prešov 1979–85)

Rudlovchak, O. Bilia dzherel suchasnosti: Rozvidky, statti, narysy (Bratislava–Prešov 1981)

Magocsi, P. R. The Rusyn–Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia: An Historical Survey (Vienna 1983)

Pekar, A. B. The History of the Church in Carpathian Rus’ (New York 1992)

Paul Robert Magocsi

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)