Portraiture

Portraiture [портретистика; portretystyka]. The artistic depiction of one or more particular persons. The oldest form of secular art in Ukraine, it dates back to the 4th-century BC portraits found in burial sights in Chersonese Taurica. Medieval examples are the depictions of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and his family (1044) in the frescoes of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv and the depictions of Grand Prince Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych and his family in the illuminations of the Izbornik of Sviatoslav (1073). Prince Yaropolk Iziaslavych and his wife, Kunigunde-Irina, are shown in the Trier Psalter (1078–87).

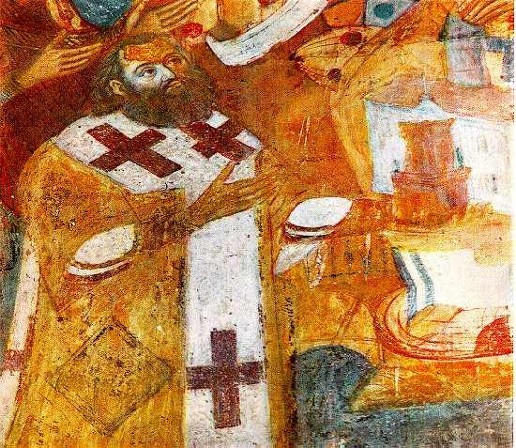

Although portraiture did not emerge as a separate genre until the 16th century, its existence may be traced back to the canonical renderings of Saint Anthony of the Caves and Saint Theodosius of the Caves in the Holy Protectress of the Caves icon (ca 1288), where they have been given individualized features. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries the rendering of icon countenances became more realistic as a result of Renaissance influences (eg, the Krasiv Mother of God). In the 17th century, realistic portrayals of patrons were part of the composition of icons, such as the Crucifixion, with a portrait of Leontii Svichka, by Y. Ivanovych, the Holy Protectress, with a portrait of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the fresco Supplication (1644–6), with Metropolitan Petro Mohyla, in the Transfiguration Church in Berestove in Kyiv.

Late 16th- to 18th-century religious and secular portraits at first had some characteristics of the icon, such as flattened forms, static frontal composition, and hieratic figural representation. With time, under the influence of Renaissance painting, they became three-dimensional and were painted with a linear and aerial perspective. Many portraits of patrons of shrines and churches were painted and displayed inside churches. In one of the earliest surviving portraits of this type, that of J. Herburt (ca 1578), only the face and hands show signs of modeling. The later portrait of Konstiantyn Korniakt (1630s) is more three-dimensional, but its composition is static. A portrait of T. Palii (ca 1711), however, is rendered rather flatly and hieratically, her garments decoratively silhouetted against a shallow backdrop.

Memorial portraits of members of the upper classes were painted on wood or metal and attached to the lids of their coffins. One of the most sensitive and beautifully modeled was that of V. Lanhysh (1635), found in the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood's portrait collection. Thought to be by Mykola Petrakhnovych, it was painted in oils on a metal oval. Portraits were also painted on banners used at funerals; the one of Konstiantyn Korniakt (1603) is an outstanding example. Small votive pictures with unsophisticated portrayals of deceased individuals, such as F. Stefanykova (1618), S. Komarnytsky (1654), and I. Vykotsky (1677), were also popular.

The rich also commissioned sculptural depictions of deceased family members, which were set atop tombstones; notable cemetery sculptures were those of Prince Kostiantyn Ostrozky (1579), O. Lahodovsky (1573), the Sieniawski family (ca 1573–1642) in Berezhany, K. Romultova (1572) in Drohobych, and Adam Kysil (1653) in Nyzkynychi, Volhynia.

Secular portraits of nobles, notable Cossacks, peasant leaders, and rich burghers gained currency in the 16th century and grew in popularity through the 17th and 18th centuries. A portrait of the Polish king Stephen Báthory (ca 1578) painted by the Lviv guild artist V. Stefanovsky during the king's visit to Lviv was a realistic depiction without the pomposity and idealization prevalent in portraits of that time. A special type of portrait painting developed in Ukraine, the parsunnyi (from the Latin persona), depicting notable figures in rich attire and formal poses against a background reaffirming their official status; included in this category are portraits of K. Zbarazky (1620s), Hetman Ivan Samoilovych (1674), Mykhailo A. Myklashevsky (ca 1700), V. Darahan (1760s), and H. Hamaliia (1750s).

During the baroque period of the late 17th and early 18th centuries many official portraits of Cossack hetmans, including Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Ivan Mazepa, Danylo Apostol, Ivan Skoropadsky, and Pavlo Polubotok, were painted depicting the regalia of office. Church leaders were also well represented in portraiture (eg, Yosaaf Krokovsky, 1718; Dymytrii Tuptalo, 1752). Family portraits mirrored social and historical changes in their composition and the manner in which the subjects were painted. The portrait of Col Semen Sulyma and his wife (1754), for example, depicts them in the elaborate dress of Cossack leaders, whereas that of their son and his wife (1780s) portrays them as typical courtiers.

Until the 18th century, artists rarely signed their works. Of the few names of portraitists that are known, Fedir Senkovych, Mykola Petrakhnovych, Vasyl of Lviv, Ivan Rutkovych, Oleksander Lianytsky, Master Samuil, and Master Andrii deserve mention. The development of regional styles gave rise to the Kyivan, Galician, and Volhynian schools of portrait painting. Portraits were also made by engravers, such as Leontii Tarasevych, Oleksander Tarasevych (K. Klokotsky, 1685), Ivan Shchyrsky (V. Yasynsky, 1707), O. Irkliivsky, and Hryhorii K. Levytsky (portrait of Rafail Zaborovsky, 1739). L. Tarasevych was the most prominent portraitist of royalty and nobility (eg, Princess Sofiia Alekseevna, 1689; K.-S. Radziwiłł, 1692). Danylo Haliakhovsky was the author of the engraving of Ivan Mazepa printed in a scholarly tract.

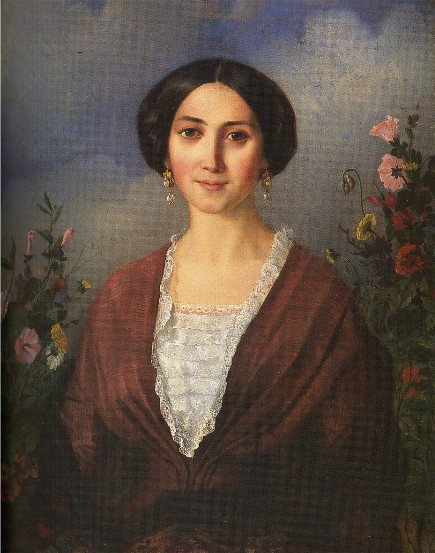

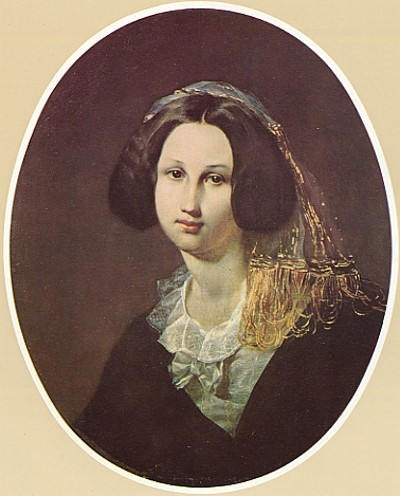

The tsarist abolition of Ukrainian autonomy in the 18th century coincided with the establishment of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1758), which attracted many Ukrainian artists. Dmytro H. Levytsky of Kyiv became a professor at the academy and the greatest portraitist in the Russian Empire of his time. Volodymyr Borovykovsky, another outstanding portraitist, also worked in Saint Petersburg in the classical, academic manner favored by the imperial court. In the 19th century many portraits were painted in Ukraine by trainees of the academy (Vasilii Tropinin, Apollon Mokrytsky, Kapiton Pavlov, Havrylo Vasko) and of guild workshops (H. Hanetsky, H. Kushliansky) as well as by self-taught artists (M. Dykov, I. Sliusarenko) and amateurs (O. Berdiaeva, Hlafira Psol). Among the many portraits painted, Portrait of My Wife (1835) by Mokrytsky and Portrait of a Young Man (1847) by Vasko stand out. Portraits were also painted by wandering artists (P. Orlov, K. Yushkevych-Stakhovsky) and by artists who were formers serfs, such as D. Maliarenko, Ivan Shapovalenko, I. Zaitsev, I. Zasidatel, and Taras Shevchenko, whose contribution to the Ukrainian art has often been underrated. Shevchenko's portraits displayed a broad social range of subjects, from peasants (The Kazakh Girl, 1856) to nobility (Princess E. Keikuatova, 1847), and sensitive three-dimensional modeling with light. He painted over 150 portraits, 43 of them self-portraits.

Portraits remained popular throughout the 19th century. They were done by most artists, including Mykola Ge (Portrait of Mykola Kostomarov, 1870), Mykola I. Murashko (Portrait of M. Ge, 1906), Mykola Kuznetsov (Portrait of P. Tchaikovsky, 1893), Mykola Pymonenko (Portrait of the Wife in Green Dress, 1893), Hryhorii Tsyss (V. Mahdenko, 1910), and Kyriak Kostandi (Portrait of M. Kniazeva, 1898). Porfyrii Martynovych created strong images of Ukrainian peasants (H. Honchar, Portrait, 1870s), and Serhii Vasylkivsky specialized in historical portraits, including ones of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Petro Mohyla, and Ivan Gonta. Women artists who painted portraits included Mariia Raievska-Ivanova (Self-Portrait, 1866) and Mariia Bashkirtseva (Portrait of a Parisienne, 1883), who worked mostly in France.

In the 20th century, artists have created portraits in a variety of styles. Oleksander Murashko, famous for his Girl in a Red Hat (1902–3), experimented with impressionist light effects (Zhorzh and Oleksandra Murashko, 1904–8; Portrait of a Peasant Family, 1914). Fedir Krychevsky's interest in impressionism, postimpressionism, and cubo-futurism can be seen in his Girl in Pale Blue (1904), H. Pavlutsky (1922), and N. Krychevska (1926) respectively. In the 1930s he turned to more realistic depictions (Happy Dairymaids, 1937). Mykhailo Zhuk painted a variety of portraits, including some with cubist analysis of space (P. Tychyna, 1919). Anatol Petrytsky painted a series of over 150 portraits of the leading Ukrainian cultural figures in the 1920s and 1930s. Among the followers of Mykhailo Boichuk, Oksana Pavlenko devoted considerable time to self-portraits and portraits of women (Mariika, 1920; Self-Portrait, 1925, 1930, 1970). Anatol Petrytsky, who explored cubo-futurism, deserves special mention for creating, between 1928 and 1933, 150 portraits of Ukrainian cultural figures; tragically, most disappeared or were destroyed during the Stalinist terror.

With the imposition of socialist realism by the Soviet regime in the early 1930s, all open explorations in modernism came to a standstill. Thenceforth most portraits created in Soviet Ukraine portrayed Communist party leaders, revolutionary figures, and workers, peasants, and soldiers in an idealized manner. Among the more versatile portraitists working within the framework of socialist realism were Oleksii Shovkunenko (M. Rylsky, 1944–5), Volodymyr Kostetsky (P. Voronko, 1945), and the graphic artist Vasyl Kasiian (a series of etchings of Vladimir Lenin, 1947; and the often-reproduced portrait of Taras Shevchenko, 1960). Mykhailo Bozhii painted several portraits of Lenin and of Shevchenko.

In Western Ukraine under Austro-Hungarian and Polish interwar rule, portraitists painted in the styles popular in Western Europe. Ivan Trush painted prominent Ukrainian writers, such as Ivan Franko (1897), Vasyl Stefanyk (1897), and Lesia Ukrainka (1900). The best-known portraitist in Lviv was Oleksa Novakivsky, who painted numerous portraits in a modified impressionist (Portrait of My Wife, 1906) and later an expressionist manner (Self-Portrait, 1927; Oleksa Dovbush, 1931). Olena Kulchytska also used an impressionist palette in her early works (Portrait of My Sister Olha, 1912). In 1920 she rendered a series of linocut portraits of Ukrainian literary figures.

After Western Ukraine became part of the USSR in 1944, artists were required to produce socialist-realist portraits (eg, Vitold Manastyrsky's Highlander, 1949). During the Nikita Khrushchev cultural thaw, however, many Lviv artists returned to exploring a variety of figural styles. Portraits of women in Hutsul dress have been painted by Manastyrsky (Marichka, 1973) and Hryhorii Smolsky (The Fiancée, 1960). Margit Selska painted several portraits in a semiabstract manner, using flattened areas of color and heavy textures (R. Selsky, 1968). D. Dovboshynsky has worked with heavy impasto and vibrant hues (R. Turyn, 1984); Volodymyr Patyk's portraits have been rendered in an expressionist manner (Woman from Rusiv, 1971). Of the younger artists Liubomyr Medvid has painted portraits in a superrealistic manner without any details (Portrait of My Wife, 1968; S. Liudkevych, 1980).

Of the portrait painters in Transcarpathia, Adalbert Erdeli painted Young Woman (1940) and Engaged Couple (1953) in bold, vibrant colors and with the subjects wearing folk dress, as did Andrii Kotska (Highland Woman, 1956, 1970).

In Soviet Ukraine from the 1930s, most sculptural portraits were of Communist party leaders, revolutionaries, and workers rendered in a heroic, idealized manner (Petr Ulianov's October Hero, 1931; I. Yakunin's V. Lenin, 1968). Busts and full-length figures of writers and artists have also been popular (Ivan Severa's I. Franko, 1947; Emmanuil Mysko's Portrait of a Young Architect, 1972). Most were commissioned for public display. Officially favored sculptors included Mykhailo Lysenko, Ivan Znoba, Yakiv Chaika, Severa, Halyna Kalchenko, Yulii Synkevych, H. Redko, and Dmytro Krvavych.

Not all postwar Soviet Ukrainian artists adhered strictly to socialist realism, however. In sculpture M. Hrytsiuk modeled sensitive and intimate portraits (Rostropovich; Valia, 1969), and in painting Opanas Zalyvakha chose subjects not sanctioned officially (Hetman Kalnyshevsky, 1964) and a manner of depiction labeled as formalist.

In Kyiv Ivan Marchuk turned to portraiture in the 1980s and painted several starkly modeled, intimate portraits against fantastically rendered backgrounds (S. Pavlychko, 1982) and neutral settings (R. Selsky, 1982). One of the more impressive portraitists of a classical style is Borys Plaksii. Among the Kyiv women artists Tetiana Yablonska, V. Vyrodova-Gotie, and V. Kuleba-Barynova painted portraits of children and adults.

Ukrainian portraitists also worked outside their homeland. Mykhailo Parashchuk, a sculptor who modeled expressive busts of Vasyl Stefanyk and Stanyslav Liudkevych in 1906 while still in Lviv, worked in Sofia, Bulgaria, from 1922. The world-renowned sculptor Alexander Archipenko left Kyiv in 1908 and worked thereafter in France, Germany, and the United States. He created several busts of Taras Shevchenko as well as portraits of his wife, Angelica. Vasyl Masiutyn, who lived in Berlin from 1921, created 63 medallions of Ukrainian political and cultural leaders and busts of Hetmans Petro Doroshenko and Ivan Mazepa. Hryhorii Kruk, who worked in postwar Munich, modeled and carved memorable heads of children (Portrait of Peter) and intimate portraits of his contemporaries (A. Zhuk, V. Kubijovyč, and V. Yaniv).

Several postwar émigré artists in North America have devoted considerable time to painting portraits in a variety of figurative styles: Jacques Hnizdovsky (K. Antonovych, 1972), Mykhailo Dmytrenko (Romtsia Savchuk, 1966), Petro Andrusiv (The Painter's Wife, 1955), Petro Mehyk (The Sculptor V. Simiantsev, 1978), Liuboslav Hutsaliuk (Renata, 1958) in the United States, and Kateryna Antonovych (Woman from Bukovyna, 1956), Myron Levytsky (Self-Portrait, 1948, 1951, 1960), and Andrii Babych (Vera, 1979) in Canada. Leonid Molodozhanyn, who settled in Winnipeg, gained an international reputation for his sculptural portraits of famous people. Emigré sculptors who have worked in the United States are Mykhailo Chereshnovsky (Y. Hirniak, Lesia Ukrainka), Serhii Lytvynenko (E. Andiievska, 1962), and Valentyn Simiantsev (Prof. A. Shtefan, 1948).

Among the postwar generation of artists of Ukrainian origin born in North America, portraiture has been central to the work of L. Bodnar-Balahutrak, who paints close-up likenesses in a photorealist manner (The Madonna Complex, 1981).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Holubets’, Mykola. Ukraïns’ke maliarstvo XVI–XVII stolit’ pid pokrovom Stavropihiï (Lviv 1920)

Shcherbakivs’kyi, D; Ernst, Fedir. Ukraïns’kyi portret: Vystavka ukraïns’koho portretu XVII–XX st. (Kyiv 1925)

Ovsiichuk, V. L’vivs’kyi portret XVI–XVIII st.: Kataloh vystavky (Kyiv 1967)

Bilets’kyi, P. Ukraïns’kyi portretnyi zhyvopys XVII–XVIII st. (Kyiv 1969)

Ruban, V. Ukraïns’kyi radians’kyi portretnyi zhyvopys (Kyiv 1977)

Zholtovs’kyi, Petro. Ukraïns’kyi zhyvopys XVII–XVIII st. (Kyiv 1978)

Ruban, V. Portret u tvorchosti ukraïns’kykh zhyvopystsiv (Kyiv 1979)

Beletskii, P. Ukrainskaia portretnaia zhivopis’ XVII–XVIII vv. (Leningrad 1981)

Ruban, Valentyna. Ukraïns’kyi portretnyi zhyvopys pershoï polovyny XIX st. (Kyiv 1984)

———. Ukraïns’kyi portretnyi zhyvopys druhoï polovyny XIX–pochatku XX stolittia (Kyiv 1986)

———. Zabytye imena: Rasskazy ob ukrainskikh khudozhnikakh XIX–nachala XX veka (Kyiv 1990)

———. (ed). Anatol’ Petryts’kyi: Portrety suchasnykiv: Al’bom (Kyiv 1991)

Valentyna Ruban, Daria Zelska-Darewych

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]

.jpg)

portrait_1603.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1904).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)