Political prisoners

Political prisoners [політичні в’язні; politychni viazni]. Persons imprisoned for their political beliefs or activities or for committing a political crime. Imprisonment for political reasons is a modern phenomenon connected to the introduction of criminal and criminal-procedure codes, state courts, and limitations on monarchical absolutism. The first such political prisoners in Ukraine were incarcerated under Austrian rule in the early 19th century and under Russian rule in the later 19th century. Up to that time, particularly during the period of unchecked absolutism, the concept of political prisoner was unclear, and imprisonment and exile were matters of the monarch's discretion rather than consequences of proven guilt. Pavlo Polubotok, Petro Kalnyshevsky, and other representatives of the Cossack starshyna became political prisoners by tsarist fiat. Taras Shevchenko was exiled as a result not of a judicial process but of an administrative decision. Political trials and an increase in the number of political prisoners often occur after ‘illegal’ means are used to combat a government. Political trials were rare in Ukraine prior to 1914.

Ukrainian SSR. From the beginning of Soviet rule, the authorities and their terroristic apparat sought to liquidate or isolate persons they did not trust because of their social origins or because of their attitudes to the state’s economic and cultural plans. Such people were considered counterrevolutionaries and ‘wreckers.’ Rarely were people repressed for actions that were truly contraventions of state laws. In fact most Soviet political prisoners did not violate any law.

In 1918 the Cheka was established in Russia to combat political crime, and the first revolutionary tribunals were set up. Their enemy was anyone who opposed Soviet rule or was a potential opponent. The definition of the ‘enemy’ changed as the Soviet state evolved, and in the 1930s it subsumed even the social class that ostensibly supported the Soviet regime, the poor peasantry. The Cheka was succeeded in 1922 by the GPU, which was replaced in 1934 by the NKVD.

In 1934 Joseph Stalin’s decrees ‘On the Investigation and Examination of Cases of Terrorist Organizations and Terrorist Actions against the Workers of Soviet Power’ and ‘On the Examination of Actions of Counterrevolutionary Sabotage and Diversions’ were included in the criminal-procedure codes of all Soviet republics, including the Criminal Procedure Code of the Ukrainian SSR. Those decrees allowed the trial and sentencing of persons 24 hours after their being officially accused, or in absentia. No provisions were made for appeals, and death sentences were carried out immediately. Such trials were conducted by oblast courts or military tribunals. All that was required as proof of guilt was a coerced confession or the secret testimony of a state operative. Trials were conducted without the accused’s being allowed even the most elementary rights and without the participation of either a prosecutor (the court itself had that function) or a defense counsel. The prosecution had unlimited rights to re-examine earlier trials and to ‘correct’ verdicts that had been handed down. Consequently, political prisoners in the 1920s and 1930s were often reincarcerated for the very same ‘offense,’ and Soviet concentration camps were soon filled with innocent people or those whose offenses were trivial.

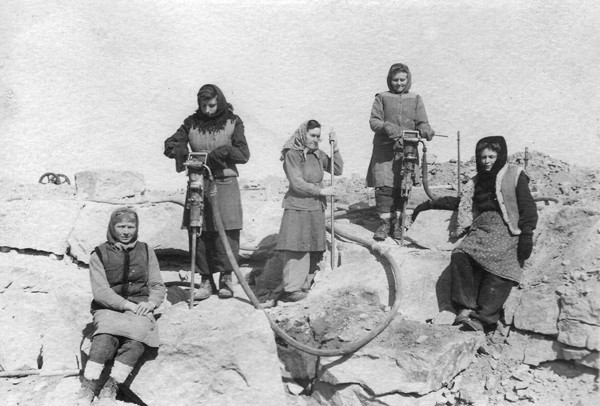

Ukrainian political prisoners in camps included both those who actively opposed the Soviet regime and those whom the Bolsheviks simply disliked or distrusted: peasants or agronomists opposed to collectivization, religious leaders, priests, believers, writers, artists, soldiers who were captured by or surrendered to the Germans during the Second World War, anyone suspected of having nationalist views, and, after 1944, members or supporters (however marginal) of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists or the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

Although political trials took place in the Ukrainian SSR from its inception, it has been impossible to obtain reliable information about most of them because they were secret or closed. The actual number of such trials has never been determined. Until recently the only available information was drawn from the testimonies and reminiscences of émigrés about the persecution of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church in the 1920s; the trials of the alleged members of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU) in 1930; the trials of Dmytro Falkivsky, Hryhorii Kosynka, Antin Krushelnytsky and his sons, and Oleksa Vlyzko in December 1934; the Trial of the 59 in January 1941; and samvydav accounts of the trials of members of the dissident movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

After the 20th CPSU Congress in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev declared that there would no longer be political prisoners, and that only those who truly committed crimes against the state would remain in labor camps. In fact, however, far from everyone imprisoned under Joseph Stalin was freed, and in the ensuing years the number of political prisoners grew as the dissident movement gained momentum. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s they included not only members of underground nationalist organizations but also those who publicly defended Ukrainian language rights and spoke out against Russification and political and religious persecution. From the 1960s on most political prisoners were charged with ‘malicious hooliganism’ or fabricated criminal offenses. The concept of political prisoner thus remained fluid, and it was not defined in the criminal code. The investigation of all ‘political’ cases was conducted by the KGB, and the courts were subordinated to it. Thus, one could say that anyone whose case was handled by the KGB was a political prisoner. Many trials continued to be held in camera or with a ‘selected’ audience.

In April 1991 over 1,100 former political prisoners gathered in Lviv to form the Association of Ukrainian Political Prisoners. I. Hubka was elected chairman of the new organization. In June 1991 the First World Congress of [former] Ukrainian Political Prisoners was held in Kyiv. Attended by some 1,000 participants from Ukraine and the West, it elected as its head the president of the recently created All-Ukrainian Society of the [Politically] Repressed, Yevhen Proniuk.

The brutal treatment of political prisoners has been documented in the writings of former prisoners, such as Valentyn Moroz, Petro Grigorenko, Leonid Pliushch, Mykhailo Osadchy, Semen Pidhainy, Danylo Shumuk, Hryhory Kostiuk, and Lev Kopelev. The most comprehensive account is provided by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago.

Western Ukraine. In interwar Western Ukraine under Polish rule, the first political prisoners were former active participants in the Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia, 1918–19, civic and community leaders, and members of the underground Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO) and Communist Party of Western Ukraine (KPZU). During the Pacification of Galicia in 1930, many members of legal Ukrainian political parties were imprisoned. In the 1930s many members of the KPZU and Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) were tried and imprisoned. Hundreds of OUN members were confined in the Bereza Kartuzka concentration camp in 1934–9. Altogether in the interwar period, there were some 1,000 Ukrainian political prisoners under Polish rule. Several dozen were executed.

Persons accused of political crimes were tried by jury in Galicia and by regular courts in the northwestern Ukrainian lands until 1939. Extraordinary and emergency courts were convened in some cases, as, for instance, in the trials of Vasyl Bilas and Dmytro Danylyshyn in 1932. Membership in the UVO and OUN was punishable by up to several years of imprisonment, and from the mid-1930s by up to 15 years.

Political prisoners organized their own hierarchically structured communities in the Polish prisons and prison camps. They maintained internal communications, conducted political training, and co-ordinated activity (eg, hunger strikes and demands for Ukrainian newspapers, the rights to correspond, privacy, separate cells, and indictments written in Ukrainian). Such communities were illegal, but prison authorities knew about them and often negotiated directly with their leaders. Those who were sentenced to longer terms were sent to prisons in Poland proper (eg, in Tarnów, Rawicz, Wronki, Katowice, and Siedlce), where they were placed in cells with common criminals.

Political prisoners in Romanian prisons in the interwar period were mostly members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, but there were also some members of some public Ukrainian organizations.

In Transcarpathia political prisoners became a widespread phenomenon during the Hungarian occupation of 1939–44, and hundreds of people were interned in concentration camps without trial. In 1942 in Mukachevo, a military tribunal sentenced in camera over 150 members of the OUN to terms in the Sátoraljaújhely and Vác prisons. Many Communist underground members and partisans were also imprisoned.

During the Second World War hundreds of members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists were imprisoned in German concentration camps, notably in Oświęcim Concentration Camp (Auschwitz) and Sachsenhausen.

Andrii Bilynsky, Myroslav Prokop

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993).]