Peremyshl

Peremyshl [Перемишль; Peremyšl’] (Polish: Przemyśl). Map: IV-3. A city (2006 pop 66,715) on the Sian River between the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains and the Sian Lowland in Subcarpathian voivodeship. It has been a county center and, from 1975 to 1998, voivodeship center in Poland. The principal city of the Sian region and one of the oldest cities in Galicia, it has been throughout its history a major Ukrainian political, cultural, and religious center.

History. Peremyshl is first mentioned in the chronicles under the year 981, but the area has been inhabited almost continuously since the Paleolithic Period. The numerous Roman coins found in the vicinity show that by the 1st century AD Peremyshl was a significant trading post on the route between the Dnister River and the Vistula River. The discovery of a large hoard of medieval Arab coins from the 9th and 10th centuries confirmed the town's continued commercial importance. Excavations conducted in 1958–60 on Zamkova Hill support the hypothesis that as early as the 9th century Peremyshl was a capital of White Croatians and Slavonic-rite bishops (see Peremyshl eparchy): the uncovered foundations of a round chapel and a palace were built of cut stone according to the Galician-Volhynian practice, not of brick (according to the Cracow practice). Because of its border location Kyivan Rus’ and Poland, and sometimes Hungary, fought over Peremyshl. In 981 Volodymyr the Great annexed it to the Kyivan state. In 1018–31 and 1071–9 it was held by the Poles. In the late 11th century it became the seat of a separate Peremyshl principality ruled by Riuryk Rostyslavych (1087–92), Volodar Rostyslavych (1094–1124), and Volodar's sons, Rostyslav Volodarovych (1124–30) and Volodymyrko Volodarovych (1131–52). Volodymyrko brought all the Galician lands under his rule and in 1141 moved the capital to the princely Halych. In the early 13th century some rulers of Peremyshl, such as Sviatoslav Ihorovych (1206–11) and Oleksii Vsevolodovych (1231), claimed independence, until Prince Danylo Romanovych finally incorporated the whole Peremyshl region into Galicia. During Danylo's and Lev Danylovych's reigns, German merchants and tradesmen settled in the town and received the right to municipal self-government. At that time the town lay between Zamkova Hill and the Sian River.

Polish period, 1349–1772. In 1349 Peremyshl was captured by the Polish king Casimir III the Great, who built a new castle there. Under Władysław Opolczyk, the viceroy of Louis the Great of Hungary, a Roman Catholic diocese was established in Peremyshl (1375). In 1387 the town returned to Polish rule, and in 1389 King Jagiełło granted it the rights of Magdeburg law. When Polish law and administration were introduced and Rus’ voivodeship was set up in 1434, Peremyshl became a starostvo center in the new province. In 1458 it gained all the rights of a crown city.

In the late 14th century the core of the town shifted east of the old town. A large new market square and a grid of eight streets were enclosed by walls and a moat. In the early 16th century the town's area was 50 ha (similar to Lviv's). Beyond the walls lay the suburbs and, farther on, the gentry estates. Peremyshl prospered from the mid-15th to the mid-17th century. Its residents were engaged mostly in trades and crafts, such as leather-working, brewing, and weaving. Some made their living in local and transit trade. By the mid-17th century the town's population had reached 4,000. Apart from Ukrainians and Poles there were Germans (who were quickly Polonized), Armenians, and Jews, who in 1559 were given special privileges by the king. Each ethnic group lived in a different area of the town. Ukrainians lived mostly in Vladyche district and the suburbs. Ukrainian burghers had to struggle for equal rights with the Poles and organized themselves into a brotherhood. In 1592 they founded a brotherhood school, and later, a hospital. The brotherhood eventually expanded from the Orthodox cathedral to the Church of the Holy Trinity, and in 1633 it set up a printing press, which it sold in the late 17th century to the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood. By the end of the 17th century the Ukrainian community in Peremyshl was in decline, owing partly to Polish discrimination and oppression and partly to religious strife between the Orthodox and the Uniates for the Peremyshl eparchy. The strife lasted throughout the 17th century and ended in the Uniates' victory in 1691. The city became an important Polish cultural center, in which the Polish diocese, the cathedral school (later the Jesuit College), and the educated magnates played the leading role. In the 16th and early 17th centuries the Peremyshl region played a prominent role in the Polish renaissance and reformation. The town was also an important Jewish religious and cultural center.

In the late 17th and the 18th centuries Peremyshl declined. At the beginning of the 18th century its population fell to 1,700. Changing trade routes were partly responsible, but the chief cause was Poland's incessant warfare and social conflicts.

Austrian period, 1772–1918. At the first partition of Poland in 1772, Peremyshl was transferred to Austria, which sold it to Count I. Zetner in 1778. At the request of the burghers, however, Joseph II restored all the town's rights and privileges in 1789, and the town became a county center. Civil servants and tradesmen, mostly Germans and Czechs, settled in Peremyshl. The old ramparts were leveled, and the town was allowed to expand. It grew at a slow pace: in 1860 the population reached only 10,000 (compared to 70,000 in Lviv). The rate of growth increased in the later part of the 19th century as new railway lines linked Peremyshl with Cracow (1859), Lviv (1861), and Hungary (1872); railway yards and agricultural machinery factories were set up in the town, and the local fortress and garrison were expanded after 1876. In 1880 the population reached 20,700, in 1900, 46,300, and in 1910, 54,700 (including 7,500 military personnel).

Under Austrian rule new opportunities opened before the Ukrainian community in Peremyshl. Thanks to the efforts of Ivan Mohylnytsky and the support of Bishops Mykhailo Levytsky and Ivan Snihursky the city became, in the first half of the 19th century, an important Ukrainian educational center. The Societas Presbyterorum, a clerical association for publishing educational materials (est 1816), a precentors' school (est 1817), and the chapter library (later also an archive and museum) took the initiative in the educational movement. A number of Ukrainian textbooks and two grammars were published in Peremyshl. By the 1880s Peremyshl had become, after Lviv, the second-largest center for Ukrainian secondary education in Galicia. It was the home of the Peremyshl Greek Catholic Theological Seminary (revived in 1845), a bilingual women teachers' seminary (est 1870), the Ukrainian Girls' Institute in Peremyshl (est 1895), the Peremyshl State Gymnasium (est 1888), and a number of vocational schools, elementary schools, and boarding schools. Peremyshl was less important as a publishing center, yet an impressive list of periodicals as well as some religious books and school texts appeared there: the first calendars (kalendari) in Galicia, Peremyshlianyn and Peremyshlianka, the monthly Vistnyk Peremys’koï Eparkhiï (1889–1918), the literary journal Novyi halychanyn (1889), the religious monthly Poslannyk (1895–1907), the monthly Prapor (Peremyshl) (1897–1900), the farmers' monthly Hospodar (Peremyshl) (1898–1913), the weekly Selians’ka rada (1907–9), and the biweekly Peremys’kyi vistnyk (1909–14). The influence of its successful Ukrainian economic institutions and co-operatives, such as the Vira co-operative bank (est 1894), the Narodnyi Dim credit union (est 1906), the Ruthenian Savings Bank, and the Burghers' Bank, was felt far beyond the town. The noted community leaders of the period were Bishops Hryhorii Yakhymovych, Toma Poliansky, Ivan Stupnytsky, Yuliian Pelesh, and Konstantyn Chekhovych, the lawyers Teofil Kormosh and Volodymyr Zahaikevych, the businessman Ivan Borys, and the writer Hryhorii Tsehlynsky.

During the First World War the city surrendered after the second siege to the Russian army and was recaptured two months later, in June 1915, by Austrian and German forces.

Interwar period. After the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918, Peremyshl became an arena of the Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia, 1918–19. It was controlled briefly (3–12 November 1918) by the Ukrainian authorities. In 1919–21 a Polish internment camp for soldiers of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic and the Ukrainian Galician Army was located nearby, in Pykulychi. After the war Peremyshl did not grow: from 1921 to 1931 its population increased only from 48,100 to 51,000. The garrison stationed there was a burden rather than an economic advantage. The city's metallurgical and forest industries developed slowly. It remained a Ukrainian religious center: it was the seat of Bishop Yosafat Kotsylovsky and the home of the revived Peremyshl Greek Catholic Theological Seminary and of the Peremyshl Eparchy Aid Association. A Basilian monastery was built in the vicinity. A number of new cultural institutions, such as the Stryvihor Museum, and young people's and sporting organizations, such as Berkut (1922) and Sian (1929), were set up. Some new co-operatives and private enterprises were organized. The weeklies Ukraïns’kyi holos (Peremyshl) (1919–32) and Beskyd (1928–33, later Ukraïns’kyi Beskyd) appeared.

After 1939. With the Polish military collapse in the summer of 1939, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Sian River became the dividing line between the German-occupied and the Soviet-occupied territories. The city was cut into two parts. Many Ukrainians and Poles fled from the Soviet side of the river to the German side. Of those who stayed behind many were deported or shot by the Bolsheviks. Toward the end of June 1941 the whole city came under German rule.

In 1939, of 54,200 residents in Peremyshl, 8,600 (15.8 percent) were Ukrainians (2,000 of whom spoke only Polish), 27,100 (50 percent) were Poles, and 18,400 (34 percent) were Jews. According to the German census of 1942, of 34,000 city residents, 8,100 (23.9 percent) were Ukrainians, 20,200 (59.5 percent) were Poles, 3,800 (11.2 percent) were Jews, and 1,800 (5.3 percent) were Germans.

Peremyshl was recaptured by Soviet Army on 27 July 1944, and 40 percent of it was destroyed in the process. According to the Polish-Soviet agreement of 1945 Poland retained Peremyshl, and its Ukrainian population was resettled (see Resettlement) either in the Ukrainian SSR or the newly acquired territories in western Poland (see Operation Wisła). All Ukrainian schools and organizations were dissolved. Bishops Yosafat Kotsylovsky and Hryhorii Lakota, along with a group of Ukrainian priests, were arrested by the Poles and handed over to the Soviets. The Ukrainian cathedral and chapter buildings were confiscated by the Polish state. The residence of the Ukrainian bishop was converted into the People's Museum of the Przemyśl Land, and most of the holdings of the Stryvihor Museum and the Peremyshl eparchy archives were transferred to it. During the brief political thaw in 1956–60 some Ukrainian cultural activity was permitted. The Ukrainian Social and Cultural Society was formed, parallel Ukrainian-language instruction was introduced in the Polish lyceum, and a Ukrainian boarding school was opened. The last two measures were soon revoked. Peremyshl entered the 1990s with a Ukrainian Orthodox parish. Ukrainian Catholics, however, attended services in a Polish Roman Catholic church. Only in 1991 the Ukrainian Greek Catholic community in Peremyshl was given a permanent church, albeit not the former Ukrainian cathedral, but the Jesuit Church which became the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist. In 1996 another Ukrainian church in the Zasiannia district, formerly used as a building of the State Archive in Przemyśl, was returned to the Basilian monastic order and it was made available to the faithful in 1999. A Ukrainian-language elementary school, named in honor of Markiian Shashkevych, was opened in Peremyshl in 1991. Many buildings owned by Ukrainians in the past were returned to the community by the Polish state in the 2000s, including the residence of the Greek Catholic bishop and the Ukrainian People’s Home.

Cut off by the new border from its natural hinterland to the east and south, Peremyshl stagnated for a decade after the Second World War. From 1946 to 1953 its population increased only from 36,800 to 38,000. Then it began to grow, mostly because of industrial investment. It has a well-developed food industry, a building-materials industry, a metallurgical industry, a woodworking industry, and a confectionery industry. Standing at the junction of the main highways and railways, it was an important center of Polish-Soviet, and currently Polish-Ukrainian trade.

Culture. The city's contribution to Ukrainian culture was largely connected with the Ukrainian Catholic eparchy of Peremyshl (see Peremyshl eparchy). In the early 19th century most of the scholars who worked in Peremyshl, including Antin Dobriansky, Hryhorii Hynylevych, Yustyn Zhelekhovsky, Yosyp Levytsky, and Ivan Mohylnytsky, were priests. In more recent times researchers, such as Ivan Bryk, Yevhen Hrytsak, Ivan Zilynsky, Bishop Hryhorii Lakota, Stepan Shakh, and Vasyl Shchurat, worked there. Writers such as Orest Avdykovych, Petro Karmansky, Uliana Kravchenko, Pavlo Leontovych, Denys Lukiianovych, Volodymyr Masliak, Vasyl Pachovsky, Osyp Turiansky, Hryhorii Tsehlynsky, and Sylvester Yarychevsky lived and worked in the city. Its regional and diocesan museums contain many monuments of Ukrainian culture.

Peremyshl is known for its artistic traditions. The German painter Heil, who decorated Wawel Castle in Cracow in the 15th century, received an estate in Peremyshl from King Jagiełło. During Bishop A. Brylynsky's tenure (1581–91) an icon painting school was established in nearby Rybotychi (Rybotycze). In recent times the painters Teofil Kopystynsky, A. Pylykhovsky, Oleksa Skrutok, Olena Kulchytska, Olha Kulchytska, and S. Chekhovych worked in Peremyshl.

Ukrainian music was cultivated in Peremyshl. The Galician-Volhynian Chronicle under the year 1241 mentions the poet-singer Mytusa, who served at the bishop's court. In the 18th century, a musicians' guild was active in the town. In 1829 Rev Yosyp Levytsky organized a choir at the Greek Catholic Cathedral, which influenced the development of choral music in the 19th century. It was conducted by the Czech composers A. Nanke, V. Zravý, and L. Sedlák. The Ukrainian composers Ivan A. Lavrivsky and Mykhailo Verbytsky lived and worked in the city. The Boian society (est 1891) and the local branch (est 1924) of the Lysenko Music Society in Lviv fostered Ukrainian musical culture.

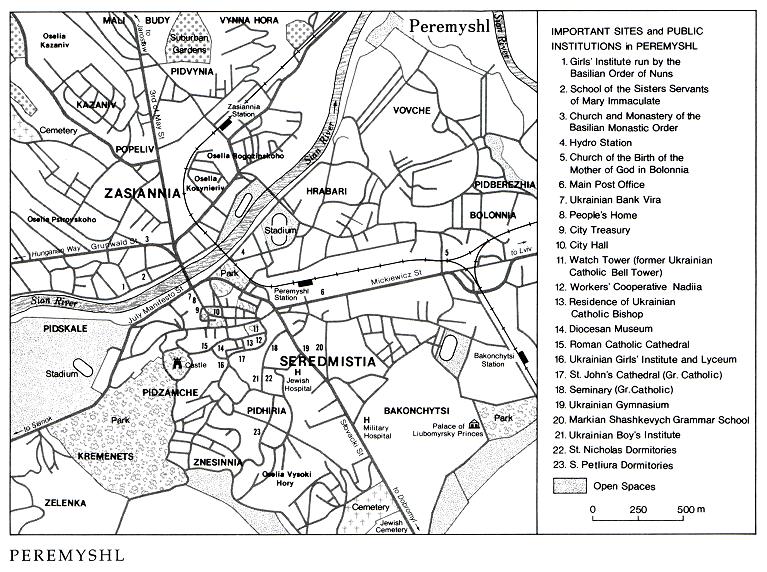

Layout and appearance. Old Peremyshl—now the city center with the Market Square—lies on the right bank of the Sian River. It has preserved some of its original character. The northern part of the old town served as the Jewish district until 1942. Today the old town is the administrative and commercial district of Peremyshl. In the 19th and early 20th centuries the city spread eastward toward Lviv along the railway line and Mickiewicz Street. It also expanded, though not as much, southeastward along Słowacki Street. Northeast of the center lies Harbari district. Today most of the industrial buildings and factories are located on the eastern outskirts of the city, in the former villages of Bakonchytsi (Bakończyce), Perekopana (Przekopana), and Korovnyky (Krówniki). A large district arose on the left bank of the Sian River, known as Zasiannia (Zasanie). In the southwestern section, on the slopes of the Carpathian Mountains foothills, lies a large municipal park.

Most of the noted architectural monuments in Peremyshl are churches. The Ukrainian Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist (a Carmelite church until 1784), which was built in the baroque style (1625–30) and restored in 1876–84, is now a Polish Catholic church. Its unique Byzantine dome was destroyed in the 1990s and replaced with a Western-style spire. The Roman Catholic Cathedral, built in 1460–1571 in the Gothic style at the site of Saint Nicholas's Church (11th–13th century), was reconstructed in 1724–44 in the baroque style. The oldest Roman Catholic churches include the baroque Jesuit Church (1622–37), the late baroque Franciscan Church (built in the gothic style in 1379, rebuilt in 1754–78 with classical elements, renovated in 1848 and 1875), and the Reformers' Church (1627, rebuilt in 1657), which contains remnants of the town wall. The Old Synagogue, built in 1579 in the Renaissance style and renovated in 1910, was active until 1942. Other architectural landmarks include the Old (or Clock) Tower (1775–7), which was to have served as the bell tower of the planned Greek Catholic Cathedral, the remains of the ramparts in Władycze district, several Renaissance and baroque buildings in the Market Square (partly destroyed in 1944 and restored), and the remnants of the 14th-century castle, which was rebuilt in the Renaissance style in 1612–30, torn down by the Austrian authorities, and then partly rebuilt in 1867, 1887, and 1912. The churches of more recent construction include the Church of the Nativity of the Theotokos (1880s), painted by O. Skrutko in 1906, the Church of Saint John the Theologian (1901) in Perekopana, and the church of the Basilian monastery (1935) in Zasiannia.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lewicki, A. Obrazki z najdawniejszych dziejów Przemyśla (Peremyshl 1881)

Hauser, L. Monografia miasta Przemyśla (Peremyshl 1883)

Orłowicz, M. Ilustrowany przewodnik po Peremyślu i okolicy (Lviv 1917)

Smolka, J. Historia miasta Przemyśla (Peremyshl 1924, 1936)

Hrytsak, Ie. Peremyshl’ tomu sto lit (Peremyshl 1936)

Al’manakh: De sribnolentyi Sian plyve (Peremyshl 1938)

Wolski, K. Przemyśl i okolice (Peremyshl 1957)

Shakh, S. Mizh Sianom i Dunaitsem, pt 1 (Munich 1960)

Tysiąc lat Przemyśla (Peremyshl 1961)

Zahaikevych, Bohdan. (ed). Peremyshl’: Zakhidnyi bastion Ukraïny (New York–Philadelphia 1961)

Ziemia Przemyska (Cracow 1963)

Pasternak, Ia. Kniazhyi horod Peremyshl’ u svitli novykh arkheolohichnykh doslidzhen’ (Chicago 1964)

Kunysz, A. Przemyśl w starożytności i średniowieczu (Rzeszów 1966)

Budziński, Tadeusz. Przemyśl (Rzeszów 1990)

Petro Isaiv, Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Marko Robert Stech

[This article was updated in 2013.]

19thcentury engraving.jpg)

main square early 20th cent.jpg)

city center view.jpg)

castle.jpg)

Ukrainian Cathedral.jpg)

(panorama).jpg)

Old Ukrainian Cathedral.jpg)

Carmelites church.jpg)

River in Peremysh (Przemysl).jpg)

former Theological Seminary.jpg)

Basilian church.jpg)

Orthodox_church.jpg)

Markiian Shashkevych elementary school.jpg)

Main Square.jpg)

Bishops residence.jpg)

Peoples Home.jpg)