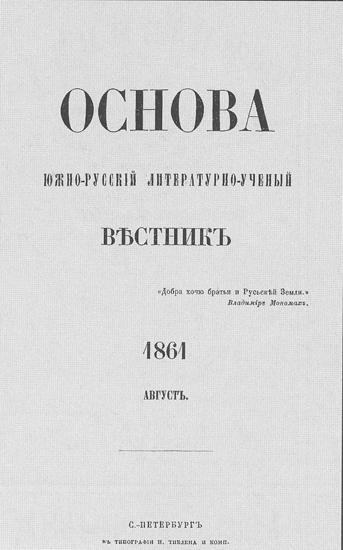

Osnova (Saint Petersburg)

Osnova (Saint Petersburg) (Foundation). A Ukrainian journal published in Saint Petersburg from January 1861 to October 1862 (a total of 22 issues) by Vasyl Bilozersky. It had a major influence on the development of Ukrainian national consciousness and Ukrainian literature in the 1860s. Bilozersky, his brother-in-law, Panteleimon Kulish, and Mykola Kostomarov were the editors; Oleksander Kistiakovsky was the assistant editor and secretary; and Danylo Kamenetsky (the director of P. Kulish's printery, which printed Osnova) and M. Shcherbak were the managers. Osnova united Ukrainophile writers and scholars in the common goal of substantiating the Ukrainians' right to develop fully and independently as a people. It published prose, poetry, folklore, and ethnographic studies in Ukrainian and historical, literary, polemical, economic, pedagogical, and musicological articles, memoirs, diaries, correspondence, news, bibliographies, and reviews mostly in Russian.

Works by over 40 belletrists appeared in Osnova, notably Taras Shevchenko (over 70 poems, including the narratives ‘Ivan Hus’ [Jan Hus] and ‘Neofity’ [Neophytes] and the play ‘Nazar Stodolia’), Leonid Hlibov, Petro Hulak-Artemovsky, Oleksa Storozhenko, Stepan Rudansky, Oleksander Konysky, Oleksander Afanasiev-Chuzhbynsky, Stepan Pysarevsky, Danylo Mordovets, Hanna Barvinok, Marko Vovchok, Yakiv Kukharenko, Mytrofan Aleksandrovych, Vsevolod Kokhovsky, Oleksander Navrotsky, Vasyl Kulyk, Petro Kuzmenko, Danylo Moroz, Borys Poznansky, and Mykola Verbytsky. Mykola Kostomarov, Panteleimon Kulish, Anatolii Svydnytsky, Matvii Nomys, Stepan Nis, Petro S. Yefymenko, and Ivan Rudchenko, besides their own work, provided ethnographic materials. Mykhailo Maksymovych, Petr Lavrovsky, Oleksander Kotliarevsky, and Oleksa Hattsuk contributed essays on the Ukrainian language. The right to public education in Ukrainian and the need for a broad network of Ukrainian-language elementary schools and textbooks and educational literature in Ukrainian were advocated by Pavlo Chubynsky, B. Poznansky, Mykhailo Levchenko, and particularly Kulish.

Panteleimon Kulish wrote most of the literary criticism and critically evaluated the Cossack era in an essay that was planned as the preface to a book on the history of Ukraine. He also wrote articles on the hetmancies of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Ivan Vyhovsky, and in five ‘Letters from the Khutir’ he condemned the culture of Ukraine's Russified towns and idealized the Ukrainian peasants' ways of life. In a historical essay on the traits of the ‘South Russian’ people, Mykola Kostomarov elaborated a new approach to Ukrainian historiography and a methodology for studying the history of the Ukrainian people. In essays entitled ‘The Federative Principle in Ancient Rus'’ and ‘Two Rus' Peoples’ he delineated the Ukrainians' independent historical and cultural development vis-à-vis that of the Russians and Poles.

Panteleimon Kulish, Mykola Kostomarov, Oleksander Lazarevsky, Tadei Rylsky, Pavlo Zhytetsky, and H. Ge contributed polemical articles in which they discussed concepts such as the family, kinship, the nation and the state, the social estates, the Ukrainian national psyche, Ukrainian-Russian and Ukrainian-Polish relations, the peasant emancipation and reforms, and other current issues. Volodymyr Antonovych contributed a ‘confession’ in which he elaborated the principles of the khlopomany. Articles on Ukrainian folk music were written by Aleksandr Serov. Kulish, Vladimir Mezhov, and Mykola Mizko contributed to the bibliographic section. Osnova also published valuable historical documents and Taras Shevchenko's diary, some of his correspondence, and memoirs of him. A news section provided information on attitudes among the peasantry and on economic matters. An album of Lev Zhemchuzhnikov's engravings of Ukrainian scenes was published as a separate appendix.

The Russian press (except for Otechestvennye zapiski and Sovremennik) reacted antagonistically to Osnova, particularly to Panteleimon Kulish's and Mykola Kostomarov's claim that the Ukrainians have a distinct language and should have their own literature. Plagued by disagreements, denunciations for fomenting separatism, police harassment, censorship, a drop in subscriptions, and financial difficulties, the editors were forced to cease publication.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zhyvotko, A. Zhurnal ‘Osnova’ 1861–1862 (Kyiv 1938)

Bernshtein, M. Zhurnal ‘Osnova’ i ukraïn’kyi literaturnyi protses kintsia 50-kh i 60-kh rokiv XIX st. (Kyiv 1959)

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]