Old Believers

Old Believers [Russian: старовери; starovery or старообрядцы; staroobriadtsy / ‘Old Ritualists’]. A grass-roots religious movement that emerged in 17th-century Muscovy as a reaction against the centralist policies of the Russian Orthodox church under Patriarch Nikon (1652–67). Nikon reformed Muscovite religious rites, customs, and particularly liturgical books, which he had amended with the aid of the Ukrainian scholars Arsenii Koretsky-Satanovsky, Teodosii Safonovych, and Yepifanii Slavynetsky to conform to Greek texts. Many Muscovite parish priests and faithful defended the old rites and texts and rejected the new, despite the support the latter were given by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich and the Muscovite government. Led by A. Petrovich, I. Neronov, and other archpriests, the Old Believers grew into a mass movement even though the Orthodox sobor of 1666–7 anathematized them and the government and church officials persecuted them as schismatics and state criminals. In the 17th century many Old Believers had chiliastic views, and over 20,000 committed suicide by self-immolation instead of waiting for the apocalypse.

The Old Believers took part in political and social movements directed against the tsarist regime, such as the 1668–76 rebellion at the monastery on the Solovets Island in the White Sea, the 1670–1 peasant uprising in southern Russia led by Stenka Razin, and the 1682 Khovanshchina rebellion around Moscow. Fleeing from brutal persecution, they founded communities in Russia’s borderlands in the north, the Urals, the Don region and the Volga region, and beyond in the Left-Bank Hetman state, Polish-ruled Belarus (Vetka in the Homel region), Right-Bank Ukraine, Bukovyna, and Moldavia.

In 1683 the Old Believers split into a moderate majority called popovtsy (‘Priestists’), who had priests (and, from the mid-19th century, bishops) and administered the Sacraments, and a radical minority called bespopovtsy (‘Priestless’), who celebrated liturgies without priests and rejected all Sacraments except baptism. The latter group underwent further sectarian splits.

The popovtsy who settled in the Left-Bank Hetman state in the 1660s formed, with the approval of Hetman Demian Mnohohrishny, ‘schismatic free settlements’ (rozkolnychi slobody) in the territories of Starodub regiment and Chernihiv regiment. Their colonization increased under hetmans Ivan Mazepa and Ivan Skoropadsky largely with the permission of local authorities (Cossack starshyna and monastic superiors, including the archimandrite of the Kyivan Cave Monastery), who expected that they would be able to turn the popovtsy into vassals after their eight-year dispensation ended. The economic strength of the free settlements, however, and Russian centralist politics to 1709 helped the Old Believers avoid subjugation. Peter I’s 1716 ukase legalized their status in the Hetman state and confirmed their rights and landholdings. According to the enumeration of 1715–8 there were 586 households in the 17 schismatic free settlements in the northern Hetman state. The settlements’ autonomy, prosperity, and commercial and manufacturing successes resulted in further repressions, this time by the Hetman state government. In 1716 and 1719 Hetman Ivan Skoropadsky forbade the Old Believers to trade in the Hetman state, but this prohibition was not enforced and his petitions to the tsar to have the Old Believers deported from the Hetman state were in vain. In the second half of the 18th century the free settlement of Klintsy in the northern Chernihiv region became the Old Believers’ cultural and publishing center; from the late 18th century it was an important woolen manufacturing center, which grew to be the largest in Ukraine by the turn of the 20th century.

The free settlements’ economic and population growth and constant conflicts with local officials and the Ukrainian government (particularly over increased taxation) caused many Old Believers in the Chernihiv region and the neighboring Homel region to move to the sparsely populated lands of Southern Ukraine. There they colonized New Serbia and Sloviano-Serbia, and later Kherson gubernia and Tavriia gubernia, particularly Beryslav and Melitopol counties. By 1832 over 7,000 Old Believers lived in Southern Ukraine. The tsarist government supported their efforts to settle Ukraine’s southern steppes and granted them various exemptions. In 1858, 10 percent of the registered Old Believers in the Russian Empire—88,762 individuals—lived in the nine Ukrainian gubernias; by far the largest concentration was in Chernihiv gubernia (51,643), followed by Podilia gubernia (9,913) and Kherson gubernia (7,105). By 1904 their number in the nine gubernias had nearly doubled, to 166,648. In the mid-18th century Old Believers also settled in southern Bessarabia, where they were known as lipovany, and near the Danube River Delta (eg, the village [now town] of Vylkove). Their in-migration increased after Bessarabia was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812, and by the late 19th century nearly 30,000 Old Believers were living in southern and northern (Khotyn county) Bessarabia.

From the 1760s to the 1780s lipovany who had emigrated to Ottoman-ruled Moldavia, Wallachia, and Bessarabia resettled in Bukovyna and Podilia with the support of Austrian authorities. In 1783 Joseph II exempted them from taxes and guaranteed their religious freedom. In Bila Krynytsia (now in Hlyboka raion, Chernivtsi oblast) the Old Believers built a monastery and a cathedral with the financial support of their coreligionists in the Russian Empire. In 1844 the settlement became the Old Believers’ episcopal see. Later a hierarchy headed by a metropolitan was established there and ordained priests and bishops for Old Believers throughout the Russian Empire. After the tsarist edict of toleration was proclaimed in 1905, the center of the popovtsy in the Russian Empire was established in Moscow at their church in the Rogozhskoe Cemetery. In 1784 there were 400 Old Believers in Bukovyna; in 1844, 2,000; in 1900, 3,110; and in 1930, 3,200. Most were popovtsy. In the 1880s and 1890s they published in Kolomyia the journals Staroobriadets and Davniaia Rus’, which were edited by N. Chernichev.

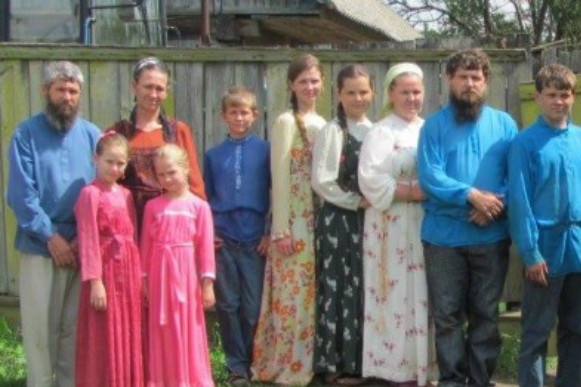

In Ukraine, as elsewhere, the Old Believers lived in separate settlements and ghettos. They considered outsiders to be unclean and thus kept contact with them to a minimum. They differed from their Ukrainian neighbors in virtually all aspects: in religion and rite, language (they spoke Russian), the construction and internal arrangement of their houses, and folkways. They wore traditional Russian clothing and did not shave, smoke, or drink alcohol, coffee, or tea. They had strict prohibitions against taverns in their settlements and rejected theater, music, and dance. Their refusal to serve in the military, to take oaths in court, and to register births, deaths, and marriages brought them into constant conflict with the authorities. The Old Believers were engaged primarily in grain and vegetable farming, orcharding, various trades, and manufacturing. Many of those living in towns were prosperous merchants and factory owners. The Old Believers facilitated the Russification of certain parts of Ukraine, particularly the northern Chernihiv region, which is now part of Briansk oblast in the Russian Federation.

Under tsarist rule in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a special department of the history of the ‘schism’ at the Kyiv Theological Academy; it was headed by Stepan Golubev.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Makarii [Bulgakov, M.]. Istoriia russkago raskola, izvestnago pod nazvaniiem staroobriadchestva, 3rd edn (Saint Petersburg 1889)

Lileev, M. Iz istorii raskola na Vetke i v Starodube XVII–XVIII vv. (Kyiv 1895)

Smirnov, P. Istoriia russkago raskola staroobriadstva, 2nd edn (Saint Petersburg 1895; repr Westmead, Hants 1971)

Kaindl, F.R. Das Entstehen und die Entwicklung der Lippowaner-Colonie in der Bukowina (Vienna 1896)

Polek, J. Die Lippowaner in der Bukowina (Chernivtsi 1899)

Zen’kovskii, S. Russkoe staroobriadchestvo: Dukhovnye dvizheniia semnadtsatogo veka (Munich 1970)

Naulko, V. Razvitie mezhetnicheskikh sviazei na Ukraine (istoriko-etnograficheskii ocherk) (Kyiv 1975)

Poliakov, L. L’Epopée des Vieux-Croyants: Une histoire de la Russie authentique (Paris 1991)

Ivan Korovytsky, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)