Mural

Mural. A large-scale artistic work created as a permanent part of an architectural structure with the use of media such as buon fresco or fresco secco, mosaic, egg tempera, or various glue, oil, or polymer paints.

The earliest existing examples of murals in Ukraine are fragments of fresco paintings from the Greek colonies on the northern Black Sea coast (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast). Mosaics and frescoes were used in the mural decorations of churches in Kyivan Rus’.

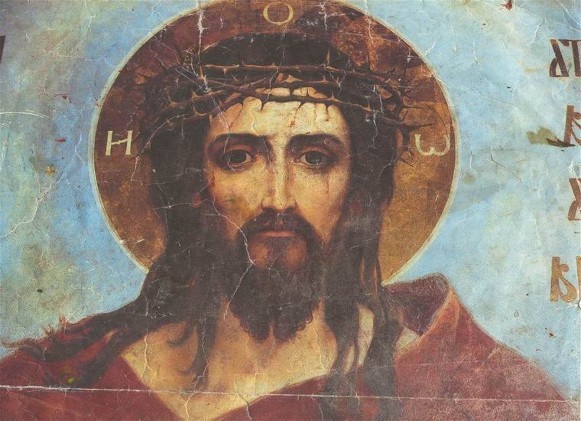

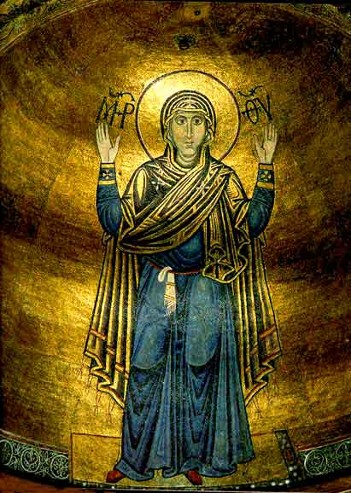

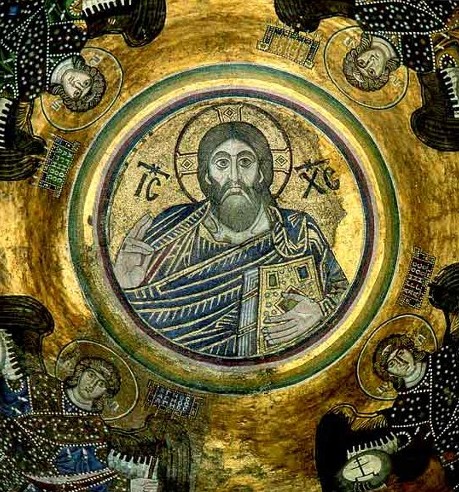

The most spectacular and complete extant mural cycles from that period are found in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. Most of the major mosaics there have been preserved, including the grand, 5.45-m Orante, in the apse, and the Deesis, in the main dome. Apart from the fine mosaic the Eucharist and fresco renderings of the sacrifice of Abraham, and of numerous saints, the Saint Sophia Cathedral also houses fresco portraits of the family of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and numerous secular subjects (hunting scenes, court musicians, and jesters).

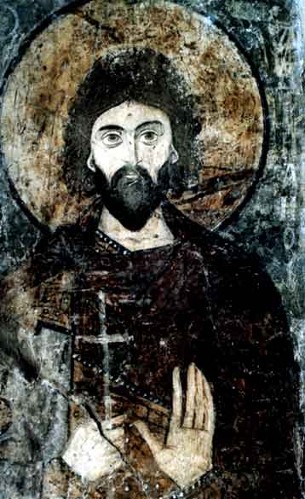

Though the murals of Kyivan Rus’ were strongly influenced by Byzantine art, they chronicle the development of an indigenous style. By the 13th century frescoes had replaced mosaics as the preferred media in mural decoration. The preserved fresco cycles of the Armenian Cathedral in Lviv (14th century) attest to stylistic changes in mural painting based on a synthesis of Byzantine and Western art.

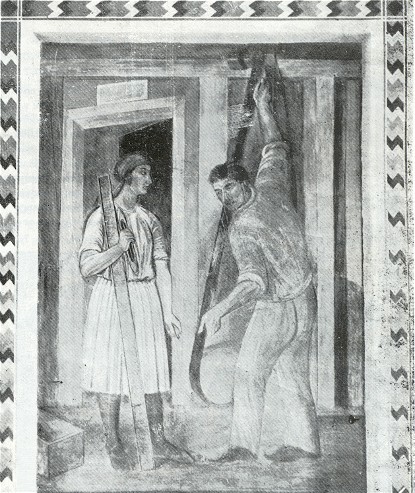

By the 17th century the use of fresco in mural painting had markedly declined. Examples of frescoes from this period have been preserved in Kyiv, in the Transfiguration Church in Berestove (1644–6). Many mural cycles from this period were painted with egg tempera on gesso, which was applied directly to the wooden structure of the church. The murals of the Potelych Church of the Holy Ghost (1620) and the Church of the Elevation of the Cross in Drohobych (ca 1636) differ greatly in style from those in the Kyivan Church of the Transfiguration. Whereas in the latter naturalistic renderings show Renaissance influences, in the Drohobych and Potelych churches the linear murals show the influence of indigenous folk-art styles.

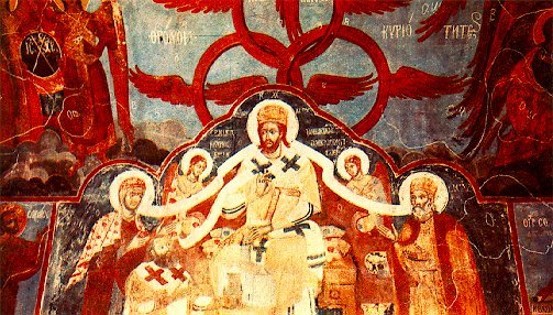

From the late 17th century a new Kyivan school of monumental painting flourished. By the third decade of the 18th century, when this school reached its apex, many churches in Kyiv, Chernihiv, Poltava, and Pereiaslav had been decorated by its members. Of the Cossack baroque murals of this period only those in the Holy Trinity Church above the main gate of the Kyivan Cave Monastery have survived in good condition. They were painted in the 1720s and 1730s by artists with a solid knowledge of illusionistic figurative methods, who adapted standard Western baroque methods of depicting space and modeling form to conform to more Byzantine standards, and depicted figures with fully modeled heads and hands who are clothed in heavily gilded, ornamented, and flattened robes.

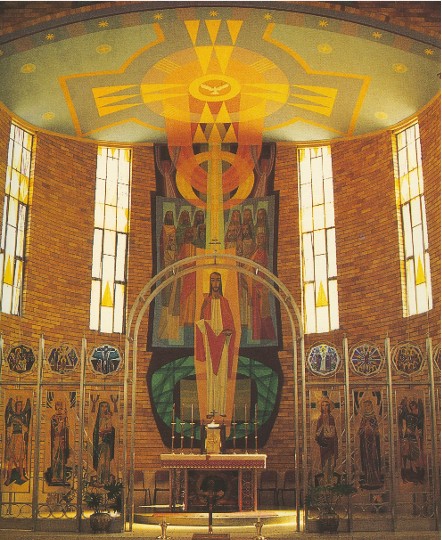

This tension between foreign art and indigenous traditions became a central problem during the revival of large-scale fresco painting in the 20th century. In the 1900s and 1910s the prominent mural painters were Serhii Vasylkivsky and Mykola Samokysh in Russian-ruled Ukraine and Modest Sosenko in Galicia. In Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s, Mykhailo Boichuk and his students (including Oksana Pavlenko, Ivan Padalka, Vasyl Sedliar, Mykola Rokytsky, Kyrylo Hvozdyk, and Manuil Shekhtman) at the Workshop of Monumental Painting in the Kyiv State Art Institute worked to revive traditional mural painting as well as to synthesize modern formalist ideas with indigenous folk and icon traditions. These artists composed numerous murals for various public buildings. Apart from the ‘Boichukists,’ Vasyl Yermilov, Lev Kramarenko, Mykola A. Pavliuk, and H. Dovzhenko extensively worked on murals combining indigenous and modernist styles. After the imposition of socialist-realist dicta in the 1930s, most of these works were destroyed.

The new stylistic imperatives of socialist realism encourage the creation of propagandistic forms of large-scale mural art. Works such as the ceiling in the vestibule of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR in Kyiv (1936–41, by V. and B. Shcherbakov), which drew on the grandiose decorative traditions of baroque painting, became popular. Apart from works apotheosizing the communist state, many monumental works with more mundane subjects, such as Mother Nursing Her Child (by Vasyl Ovchynnykov) and Harvest (by Stepan Kyrychenko and N. Klein, 1957), were commissioned for public buildings.

Outside Soviet Ukraine most mural painting has been done in churches. In interwar Galicia Petro Kholodny, Mykhailo Osinchuk, Pavlo Kovzhun, and Yurii Mahalevsky painted neo-Byzantine murals using traditional tempera techniques. In Transcarpathia, church murals were executed by Yulii Virah, Ihantii Roshkovych, and Yosyp Bokshai. Emigré artists who have worked in the large-scale format include Petro P. Kholodny, Mykhailo Dmytrenko, George (Yurii) Kozak, Myron Levytsky, Ivan Dyky, Roman Kowal, and Sviatoslav Hordynsky. One of the best examples of mural decorations in Ukrainian émigré art is Hordynsky's mosaics in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Rome.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kholotenko, Ie. Monumental’ne maliarstvo Radians’koï Ukraïny (Kyiv 1932)

Lobanovs’kyi, B. Mozaïka i freska (Kyiv 1966)

Bazhan, M.; et al (eds). Istoriia ukraïns’koho mystetstva, 6 vols (Kyiv 1966–70)

Garkusha, N.; et al. Monumental’noe i dekorativnoe iskusstvo v arkhitekture Ukrainy (Kyiv 1975)

Zholtovs’kyi, P. Monumental’nyi zhyvopys na Ukraïni XVII–XVIII st. (Kyiv 1988)

Nestor Mykytyn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1910s.jpg)

.jpg)