Monasteries

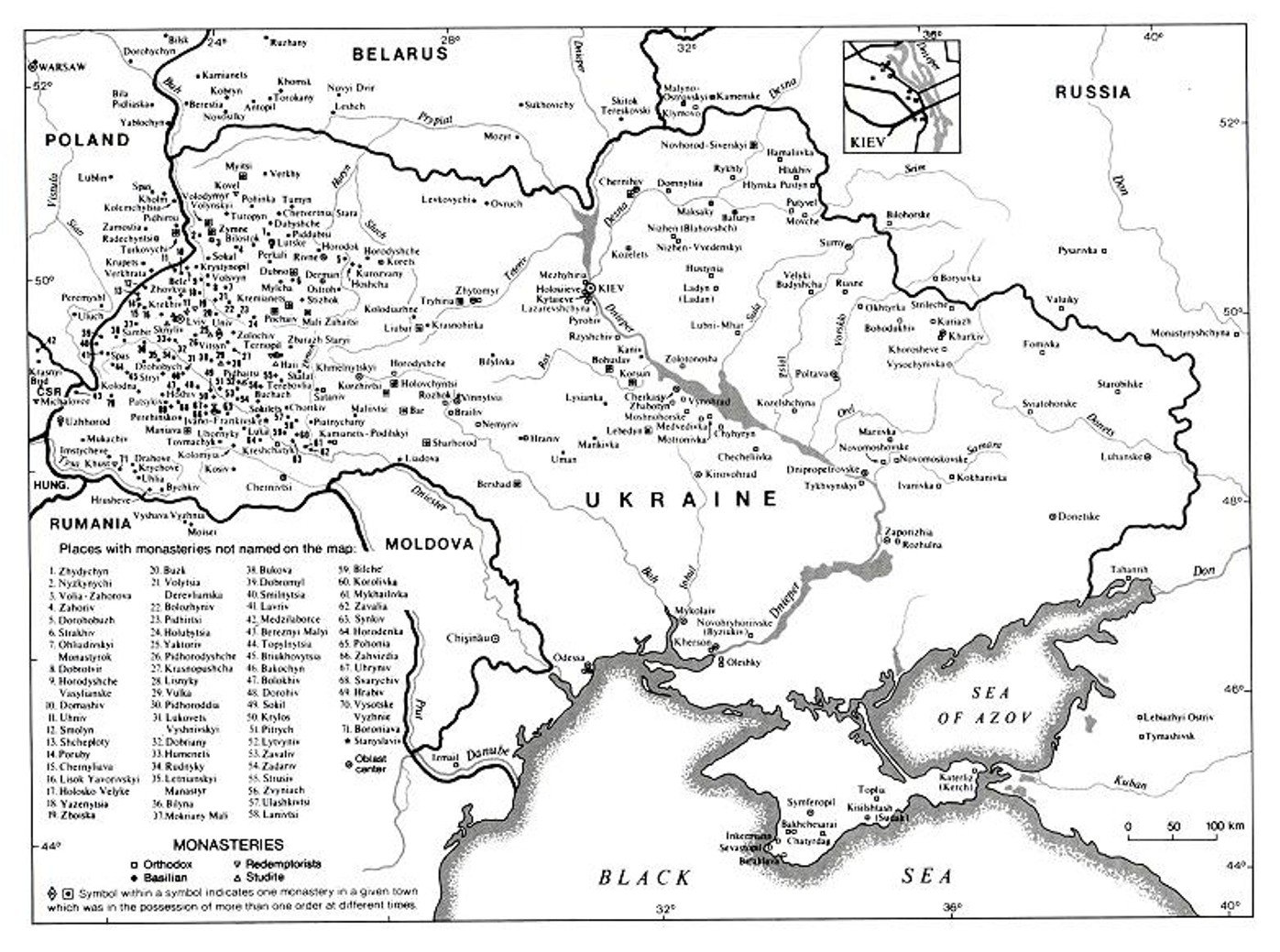

Monasteries. (Map: Monasteries in Ukraine.) Communities and settlements of monks with attendant buildings and estates. Depending on the monastic order that the particular monastery belonged to or the monastic typicon that was followed (see Monasticism), life ranged from strictly anchoritic, to semicommunal (where monks lived in individual cells but ate and prayed together), to communal or idiorrythmic. Novices also lived in the monastery before being tonsured. Monasteries were generally formally headed by a council of all the monks or nuns, which chose an abbot or overseer (an archimandrite or hegumen). Historically, depending on various political, legal, and economic conditions, monasteries enjoyed differing degrees of autonomy. Lavry (see Lavra) (of which there were three in Ukraine, the Kyivan Cave Monastery, Pochaiv Monastery, and the Sviati Hory Dormition Monastery) and stauropegion monasteries were subject only to the highest church authority (initially the Patriarch of Constantinople, later the Patriarch of Moscow and the Holy Synod) and were independent of the local bishop. Cathedral monasteries were directly subordinate to the bishop of the eparchy to which they belonged. Other types included self-administering monasteries (the majority) and hermitages (skyty, skytyky, pustyni) that were dependent on larger monasteries.

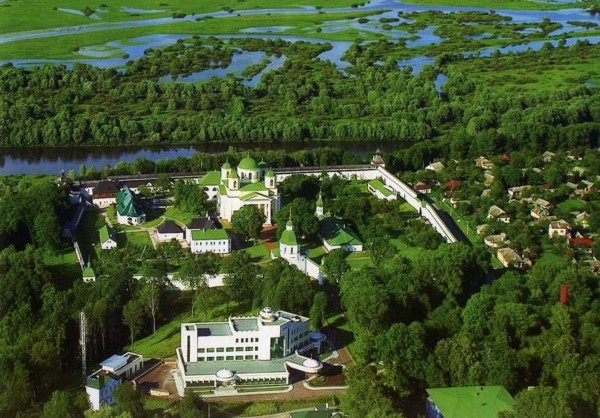

Larger monasteries had a main church and bell tower, as well as smaller chapels, baptismal alcoves, and separate refectories. Apart from the shrines and monks' residences (cells), monasteries typically had an array of administrative buildings and workshops and sometimes their own hospitals, schools, and printing presses. The monasteries were often surrounded by fortified walls or palisades, with defensive ramparts, towers, and trenches, and some monasteries even grew into large complexes that served as fortresses (especially in Slobidska Ukraine and in areas bordering the Tatar-controlled steppes).

Monastic life in Ukraine began before the official adoption of Christianity, but the first monasteries were not built until after the baptism of Kyiv and its environs in the late 10th century (see Christianization of Ukraine). The first formal monasteries were established under Yaroslav the Wise—the men's Saint George's and the women's Saint Irene's monasteries in Kyiv (both mentioned in 1037). Other early monasteries included Saint Demetrius's Monastery (later Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery), the Vydubychi Monastery, and Saint Cyril's Monastery. In the 11th to 13th centuries the number of monasteries in the Kyiv region rose to 20. Monasteries were founded in other parts of Ukraine, primarily in such princely capitals as Pereiaslav, Chernihiv (the Yeletskyi Dormition Monastery and Trinity–Saint Elijah's Monastery), Novhorod-Siverskyi, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, princely Halych, Kholm, and Lviv (Saint George's Monastery). Smaller monasteries were established throughout Ukraine. Although information about these is often incomplete, a partial list of smaller monasteries in the 11th to 13th centuries includes the Zarubyntsi (Zarub) Monastery near Kaniv, the Saints Borys and Hlib Monastery near Pereiaslav, the Zahoriv Monastery near Volodymyr-Volynskyi, the Zhydychyn Saint Nicholas's Monastery in Volhynia, Saint Daniel's Monastery in Uhrovske (Kholm region), the Synevidsko and Polonynskyi monasteries in the Carpathian Mountains, and the Rata Monastery near Rava-Ruska. Other monasteries that were probably established in the Princely era became known only in the late Middle Ages—the Mezhyhiria Transfiguration Monastery near Kyiv, the Novhorod-Siverskyi Transfiguration Monastery, the Peresopnytsia and Dorohobuzh monasteries in Volhynia, the Byblo Monastery near Peremyshl, the Horodyshche Monastery near Sokal, Saint Onuphrius's Church and Monastery in Lviv, and the Lavriv Saint Onuphrius's Monastery and Spas Monastery near Sambir.

Monasteries were established mainly by princes and boyars, although some were founded by spiritual leaders and churchmen. Noble patrons oversaw the monasteries: they cared for their growth and development and often donated estates, valuables, and money. They were thereby guaranteed certain rights over the organization and administration of the monasteries, extending to the approval of charters and the appointment of hegumens or hegumenissas. Patrons also maintained family crypts in their monasteries.

In the Princely era, monasteries became firmly established as important centers of religious, educational, scholarly, cultural, and artistic life. Their influence extended throughout Ukraine, and in some cases (eg, the Kyivan Cave Monastery) throughout Eastern Europe. Their importance in the economic life of the country was also great, particularly as a result of their colonization of outlying territories. Church peasants, essentially serfs, worked on the large monastery estates that were the basis of their wealth. Many monasteries owned mills and even workshops and small factories. In addition the defensive fortifications of monasteries made them important military installations, and they did much charitable work. The largest institutions came to exercise considerable authority in state affairs.

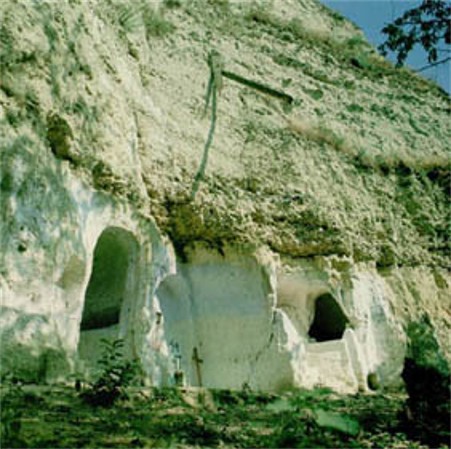

The Tatar invasions in the 13th and 14th centuries (see Tatars) brought devastation to monasteries. Many were wiped out, and the monks forced to hide in cliff-side monasteries (eg, in Bakota and Bubnyshche). Only a small number (notably the Kyivan Cave Monastery) managed to survive. After the annexation of Ukraine by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and then by Poland, new monasteries began to emerge, particularly in Galicia, where by 1500 there were 44 of them.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a revival of monastic life in Volhynia and central Ukraine. Through the efforts of Metropolitans Yov Boretsky, Isaia Kopynsky, and Petro Mohyla, and with support from the Cossacks, a series of monasteries founded in the Princely era were revived. New monasteries were also established, including the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood Monastery and Saint Nicholas's Monastery in Kyiv, the Hustynia Trinity Monastery near Pryluky, the Mhar Transfiguration Monastery near Lubny, the Krasnohiria Monastery near Zolotonosha, and the Moshnohiria Monastery near Cherkasy. In the Cossack era, monasteries again played an important role in the religious, cultural, and economic life of the country. The Cossack elite, especially under Hetmans Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Ivan Mazepa, assisted in the revival or the establishment of many monasteries, particularly in Left-Bank Ukraine. These included the Krupytskyi Saint Nicholas's Monastery near Baturyn, the Maksaky Transfiguration Monastery, the Saints Peter and Paul Monastery in Hlukhiv, the Elevation of the Cross Monastery in Poltava, the Ascension and Saint Michael's monasteries in Pereiaslav, the Annunciation Monastery in Nizhyn, and the Nativity of the Mother of God Monastery in Domnytsia near Mena. The Saint Mary the Protectress Monastery in Kharkiv and the Sviati Hory Dormition Monastery on the Donets River were established in Slobidska Ukraine, and the Samara Saint Nicholas’s Monastery was founded in the Zaporizhia. Hetman Mazepa was a generous benefactor of monasteries: he donated much money, valuable religious objects, and estates with rights for industry and trade, and granted the monasteries exemptions from taxes. After the mid-18th century, however, centralist Russian imperial policies led to a decline in the economic position of monasteries, and in 1786 Catherine II issued a ukase confiscating all their assets. Only a few were selected for state support; the rest had to generate their own income. Many smaller monasteries were closed outright.

In the century of the Church Union of Berestia (1596), most monasteries in Right-Bank Ukraine and Belarus accepted the Union and joined the Basilian monastic order, which in the 17th and 18th centuries grew to encompass approx 150 monasteries in the Ukrainian territories under Polish rule. The exceptions were the Maniava Hermitage and the so-called foreign monasteries of the Orthodox Kyiv metropoly. After the partitions of Poland, however, Joseph II introduced reforms in the Habsburg Empire that confiscated land and property from the orders and closed all but 14 of the Basilian monasteries. In Right-Bank Ukraine, which came under Russian rule, monasteries were either closed or given to the Russian Orthodox church. In 1908 there were 67 men's and 43 women's monasteries in the nine Ukrainian gubernias in the Russian Empire, plus several more in the Kuban and the ethnically Ukrainian territories in neighboring gubernias (see Table).

In Transcarpathian Ukraine the first monasteries date from the 14th century. Hrusheve in the Maramureş region (see Hrusheve Monastery) and the Chernecha Hora near Mukachevo (see Mukachevo Saint Nicholas's Monastery) were important centers, where more than 20 monastic communities of varying size were eventually established. After the Josephine reforms only seven of them remained, including the Krasný Brod Monastery, Máriapócs Monastery, and Imstycheve Monastery. These later joined with the Roman Catholic church to form a separate Basilian province. In Bukovyna there were about 30 monastic settlements, including ones in Suceava, Putna, and Drahomirna. In the late 18th century the authorities confiscated all of their holdings and abolished many of them. In Right-Bank Ukraine and, until 1648, Left-Bank Ukraine there were also a number of Roman Catholic monasteries (of the Bernardines, Dominican order, Jesuits, Carmelites, and others) established under Polish rule.

Throughout history monasteries exerted a great influence on Ukrainian culture. In the Middle Ages and Cossack era they were the principal centers of education and scholarship. The Povist’ vremennykh lit, the Mezhyhiria Chronicle and Hustynia Chronicle, and important manuscripts, such as the Horodyshche Apostolos and Horodyshche Gospel, the Byblo Apostolos, the Putna Gospel, and the Peresopnytsia Gospel, were all compiled in monasteries. With the introduction of printing, many monasteries (especially in Derman, Chernihiv, Pochaiv, Suprasl, Univ, Kyiv, and Lviv—see Derman Monastery, Trinity–Saint Elijah's Monastery, Pochaiv Monastery Press, Kyivan Cave Monastery Press, Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press) became the earliest and most important publishers in Ukraine; they issued secular as well as religious works in a variety of languages. Many of the earliest schools were established at monasteries or in affiliation with them: the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School and Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School; the Chernihiv College, Pereiaslav College, and Kharkiv College; and even the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. Liturgical singing, icon painting (see Kyivan Cave Monastery Icon Painting and Art Studio), the graphic art (esp engraving), fresco painting, embroidery (in women's monasteries), and other art forms flourished in monasteries, and many monasteries maintained important libraries and fostered the development of historiography and literature.

Churches, bell towers, and other monastery buildings are important examples of Ukrainian architecture. Shrines of the 11th to 12th centuries—eg, the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery and Trinity Church of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, the cathedrals of the Vydubychi Monastery and Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, the Transfiguration Church in Berestove in Kyiv, the Dormition Cathedral of the Yeletskyi Dormition Monastery in Chernihiv, and Saint Panteleimon's Church in Halych—were generally three-nave buildings in the Byzantine style, although the last two show Romanesque influences. Monastery churches of the 12th century (eg, Saint Elijah's Church in Halych and Saint Basil's Church of the Zymne Monastery, near Volodymyr-Volynskyi) often included rotundas; in the 15th to 16th centuries three-conch shrines of the Byzantine Renaissance were common (eg, churches of the Lavriv Saint Onuphrius's Monastery and the SS Peter and Paul Church in Kamianets-Podilskyi). Later monasteries were built in various styles: the late Gothic style (eg, the Trinity Church in Mezhyrich, near Ostroh; the Dormition Church in Zymne; and the gate tower of the Derman Monastery), Renaissance (16th–17th century; eg, the monastic church in Zaluzhia, near Zbarazh; the reconstructions of monasteries of the Princely era in Kyiv made under Petro Mohyla; the Church of the Protectress in the Nyzkynychi Monastery), Cossack baroque (17th–18th centuries; eg, the Trinity and Saints Peter and Paul churches of the Hustynia Trinity Monastery, the All Saints', Resurrection, and Saints Peter and Paul churches of the Kyivan Cave Monastery; and other five-domed monastic shrines), and rococo (18th century; eg, the bell tower of the Pochaiv Monastery). The wooden churches and bell towers of the Mezhyhiria Transfiguration Monastery (1611), the Krekhiv Monastery (1658), the Maniava Hermitage (1676), and the Moshnohiria and Medvediv monasteries also had a distinctive style. In the 19th and 20th centuries very few new monasteries were built in Russian-ruled Ukraine, and those were constructed according to local designs or in a Muscovite style (eg, the refectory of the Kyivan Cave Monastery, 1900, and the Trinity Cathedral in Pochaiv, 1906) that stood in stark contrast to the style of the older structures. In Galicia and Transcarpathian Ukraine, notable monastery buildings included the Basilian churches in Hoshiv and at the Zhovkva Monastery, the churches of the Basilian women's monasteries in Lviv and Stanyslaviv, and the churches of the Redemptorist monasteries (see Redemptorist Fathers) in Mykhailivtsi and the Prešov region. Generally, Ukrainian Catholic monasteries were smaller than Orthodox ones and much less ornate.

The Bolshevik occupation of Ukraine brought ruin to virtually all monasteries. On the basis of a decree issued in January 1918, all monastic holdings were nationalized, and the monasteries were abolished and liquidated. The artistic valuables they held, including liturgical objects, icons, decorations, and books, were confiscated, and most were destroyed. Many valuable iconostases were demolished. Even the monastery buildings, of immeasurable historical and artistic value, were razed, particularly in the early 1930s.

During the German occupation of Ukraine in 1941–3, a number of Orthodox monasteries were reopened. After the Second World War, as a result of the new religious policy adopted by the Soviet government, some were allowed to stay open. All Ukrainian Catholic monasteries (over 150 of them) in the newly occupied territories, however, were closed. In 1954 there were approx 39 active monasteries and hermitages in the Ukrainian SSR, as compared with 69 in all of the USSR. Of these, 14 were in Transcarpathia. There were few in central and eastern Ukraine, among them the half-ruined Kyivan Cave Monastery, two women’s monasteries in Kyiv, and the Dormition Monastery in Odesa. In 1954 the antireligious campaign resumed, and most of the remaining monasteries were closed. The Kyivan Cave Monastery was closed in 1964, but part of it was returned to the Russian Orthodox church in 1988 on the occasion of the millennium of the Christianization of Ukraine. By 1970 there were only seven monasteries open (two men's and five women’s), with a total of approx 800 (mostly elderly) monks and nuns. Many monasteries were re-opened after Ukraine gained independence in 1991. In the Ukrainian diaspora, there are now over 250 Ukrainian Catholic men's and women's monasteries and monks’ communities. The Ukrainian Orthodox church has one in the United States.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zverinskii, V. Materialy dlia istoriko-topograficheskogo issledovaniia o pravoslavnykh monastyriakh v Rossiiskoi Imperii s bibliograficheskim ukazatelem, 3 vols (Saint Petersburg 1890–7)

Setsinskii, E. ‘Materialy dlia istorii monastyrei Podol'skoi eparkhii,’ Trudy Podol'skogo istoriko-statisticheskogo komiteta, vol 5 (1891)

Titov, F. ‘O zagranichnykh monastyriakh Kievskoi eparkhii XVII–XVIII vv.,’ TKDA, 1905, nos 1–2

Denisov, L. Pravoslavnye monastyri Rossiiskoi Imperii (Moscow 1908)

Kryp’iakevych, I. ‘Seredn’ovichni manastyri v Halychyni,’ ZChVV, nos 1–2 (1926)

Lukan', R. Vasyliians'ki manastyri v Stanyslavivs'kii eparkhiï (Lviv 1935)

Vavryk, M. Po vasyliians'kykh manastyriakh (Toronto 1958)

Zubkovets, V. Natsionalizatsiia monastyrskikh imushchestv v Sovetskoi Rossii (1917–1922 gg.) (Moscow 1975)

Libackyj, A. The Ancient Monasteries of Kiev Rus (New York 1978)

Senyk, S. Women’s Monasteries in Ukraine and Belorussia to the Period of Suppression (Rome 1983)

Mykhailo Vavryk

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)