Modernism

Modernism. An international movement in literature and art that emphasized the sense of a radical break with the past and the possibility of a transformed world. Emerging at the end of the nineteenth century as a rejection of realism and populism, it experimented with new literary and artistic forms, often under the influence of photography, film, and new technologies. Non-traditional materials were often used in architecture and sculpture, such as new metal alloys, glass, and synthetic plastics. The focus in literature and art was often on subjective perceptions and on the inner psychological conflicts and complexes of the urban intelligentsia. Depictions of individual personalities often included the eccentric, the taboo, and the deranged. Modernism coincided with and reflected the rapid growth of capitalist production and the rise of strong feminist, political, and national movements.

Central and East European modernism in the years 1880–1913 is often viewed as encompassing the “isms”: impressionism, symbolism, cubism, abstractionism, futurism, and expressionism. A second wave of modernism appeared in the years 1914–30, which was strongly influenced by radical political movements in Europe and sometimes identified itself as the cultural avant-garde of these movements. It was closely associated with the futurists, constructivists, expressionists, and surrealists of the post-First World War years.

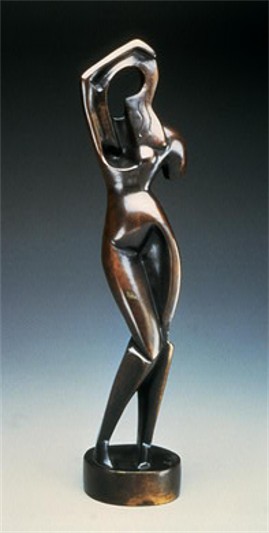

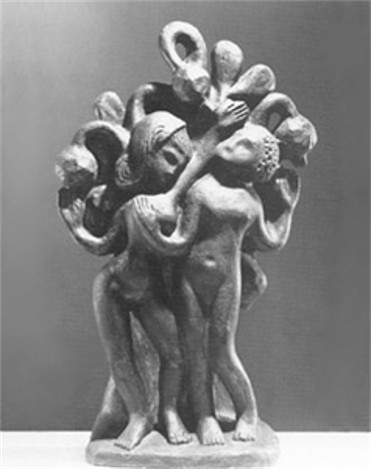

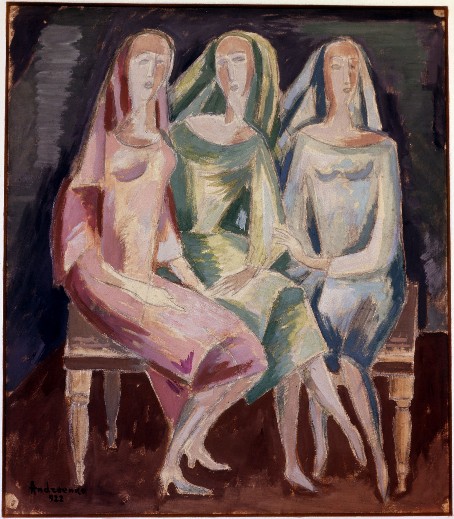

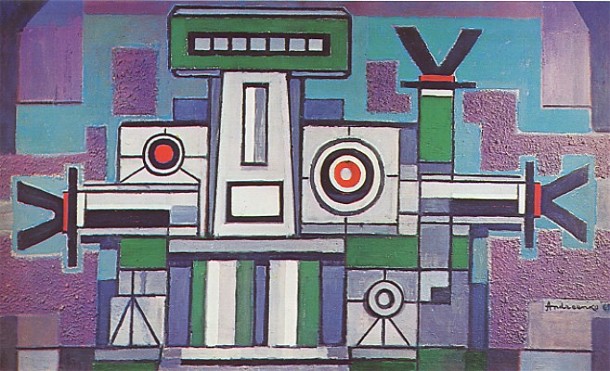

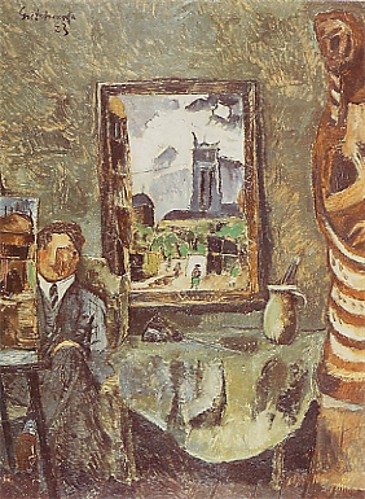

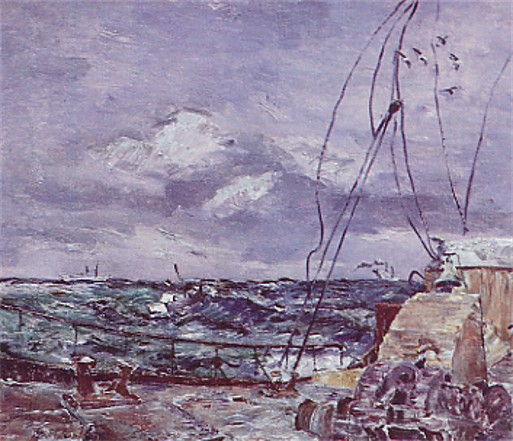

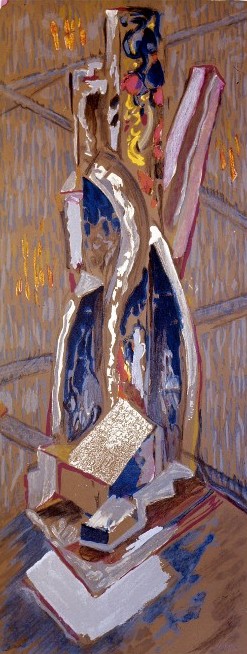

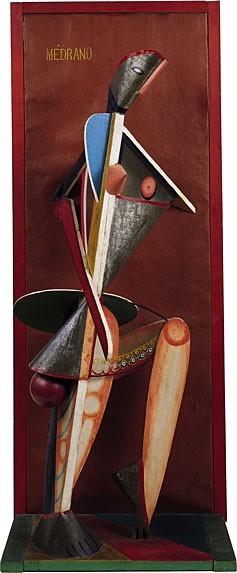

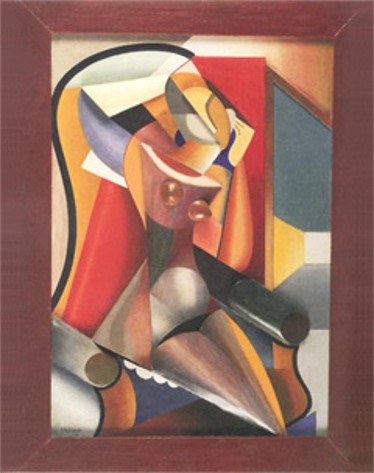

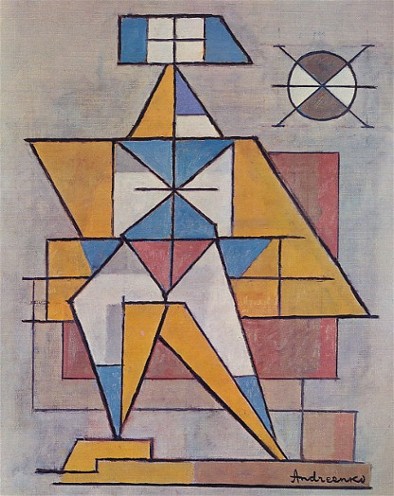

Painters and sculptors from Ukraine were very heavily involved in the artistic revolution that swept Europe in the first decade of the twentieth century. Many spent time in Western Europe, particularly in Paris, in the prewar years, among them Vadym Meller, Alexander Archipenko, Alexandra Ekster (Exter), Mykhailo Boichuk, Davyd Burliuk, Sofiia Levytska, Aleksandr Shevchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, N. Altman, and D. Shterenberg. Some, like Oleksa Hryshchenko (Alexis Gritchenko, A. Grischenko), Mykhailo Andriienko-Nechytailo (Michel Andreenko), and K. Redko came to Paris after the war, and several of them settled there permanently. Other prominent exponents of modernism in Ukrainian art were Oleksander Bohomazov, Anatol Petrytsky, Vasyl Yermilov, Viktor Palmov, Pavlo Kovzhun, Vasyl H. Krychevsky, Mykola Butovych, Halyna Mazepa, and Petro Kholodny. Some of the leading figures in the international avant-garde identified themselves as Ukrainians, among them Burliuk, the “father” of futurism in the Russian Empire, Archipenko, the maker of cubist sculptures, Kazimir Malevich, the creator of suprematist art, and Tatlin, known for his constructivism. Some of these artists were interested in provocatively flouting convention; others, in exploring the machine aesthetic and the use of new materials, still others, in utopian and visionary projects.

Ukrainian modernism was distinguished by its use of color (both Ekster and Sonia Delauney, who originally came from Ukraine, did much to introduce bright colours into Western cubism and modern design) and its special feeling for texture. Another particularly strong Ukrainian modernist feature was the interest in primitivism, the direct, powerful, and simple as expressed in folk creativity or ancient traditions. In Ukrainian architecture modernism was manifested in the revival of a Ukrainian national style in the projects of Vasyl H. Krychevsky, Konstantin Zhukov, Oleksander Tymoshenko, and Ivan Levynsky, and in the constructivism of Vladyslav Horodetsky, Petro H. Yurchenko, Yevsevii Lipetsky, S. Kravets, and others.

After the Second World War, modernism dominated in Ukrainian émigré art, particularly in the United States and Canada, in reaction to socialist realism, the only artistic method sanctioned in the USSR. Strongly influenced by abstraction and the simplified forms of modern design, a modernist esthetic can be seen in the works of Liuboslav Hutsaliuk, Myron Levytsky, Edvard Kozak, Roman Kowal, Arcadia Olenska-Petryshyn, Jurij Solovij, Konstantin Milonadis, Volodymyr Makarenko, and other émigré artists, and in the architectural projects of Radoslav Zuk and V. Deneka.

Modernism was also manifest in the productions of the Molodyi Teatr theater, the Berezil theater led by Les Kurbas, the Mykhailychenko Theater led by Marko Tereshchenko, the Zahrava experimental theater led by Volodymyr Blavatsky, and the émigré Theater-Studio of Y. Hirniak and O. Dobrovolska. It also had its expression in the 1920s in the films produced by the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration (VUFKU) studios in Soviet Ukraine (Oleksander Dovzhenko, Dziga Vertov), in the experimental films of Yevhen Slabchenko (Eugène Deslaw) in France, and in music.

Ukrainian literary modernism made its appearance at the turn of the century with the Lviv-based Moloda Muza group, who championed the idea of ‘pure art,’ and the Kyiv-based journal Ukraæns’ka khata. Mykola Vorony, an early theoretician of the movement, believed that modernism consisted of a change in thematic focus from the social to the psychological, of the enrichment of forms of versification, and of greater sophistication of metaphor. The movement dominated Ukrainian poetry after the publication of Pavlo Tychyna’s Soniashni klarnety (Sunny Clarinets, 1918) and Zamist’ sonetiv i oktav (Instead of Sonnets and Octaves, 1920). In the 1920s it was manifested in the radical poetic experiments of Mykhailo Semenko and Valeriian Polishchuk and in the poetry of Mykola Bazhan and other poets. Examples in prose include the impressionistic works of Vasyl Stefanyk and Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, the psychological prose of Volodymyr Vynnychenko and, in the 1920s, Valeriian Pidmohylny, and the experimental prose of Mykola Khvylovy’s (Syni etiudy [Blue Etudes], 1923) and Leonid Skrypnyk’s (Intelihent [The Intellectual], 1929). Ukrainian literary modernism also produced strong women writers who expressed feminist concerns (eg, Lesia Ukrainka and Olha Kobylianska). In Ukrainian émigré literature, modernism was most apparent in the work of the interwar ‘Prague school’ of Ukrainian poets and the postwar New York Group of poets.

In the early 1930s the Soviet authorities repressed and then eradicated modernism and its exponents in both literature and the arts, demanding in its place a state-sanctioned form of populism that stressed the heroic gesture and loyalty to the Communist party. Most forms of modernist experimentation were denounced as ‘formalism,’ ‘psychologism,’ ‘bourgois nationalism,’ or ‘decadence.’ Not until the 1960s did a literary movement—the shistdesiatnyky— re-emerge in Ukraine that built on the gains made by modernists in the century’s first three decades.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rudnyts’kyi, Mykhailo. Vid Myrnoho do Khvyl’ovoho (Lviv 1936)

Mudrak, Myroslava M. The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in Ukraine (Ann Arbor 1986)

Struk, Danylo Husar. ‘The Journal S’vit: A Barometer of Modernism,’ Harvard Ukrainian Studies 15, no. 3/4 (December 1991)

Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. ‘The Modernist Ideology and Mykola Khvyl’ovyi,’ Harvard Ukrainian Studies 15, no. 3/4 (December 1991)

Tarnawsky, Maxim. ‘Modernism in Ukrainian Prose,’ Harvard Ukrainian Studies\ 15, no. 3/4 (December 1991)

Grabowicz, George G. ‘Commentary: Exorcising Ukrainian Modernism,’ Harvard Ukrainian Studies 15, no. 3/4 (December 1991)

Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. ‘Ukrainian Symbolism and the Problem of Modernism,’ Canadian Slavonic Papers 34, no. 1–2 (1992)

Shkandrij, Myroslav. ‘Ukrainian Avant-Garde Prose of the Twenties,’ in Literature and Politics in Eastern Europe, ed Celia Hawkesworth (New York 1992)

Shkandrij, Myroslav. Modernists, Marxists, and the Nation: The Ukrainian Literary Discussion of the 1920s (Edmonton 1992)

Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. ‘Ukrainska khata and the Paradoxes of Ukrainian Modernism,’ Journal of Ukrainian Studies 19, no. 2 (1994)

Ilnyts’kyi, Mykola. Vid ‘Molodoï muzy’ do ‘Praz’koï shkoly’ (Lviv 1995)

Duvirak, Dagmara. “Ukraïna, Ihor Stravins’kyi i ievropeis’kyi avanhard pochatku stolittia,” in Stravins’kyi i Ukraïna (Kyiv 1996)

Syvokhip, Volodymyr, and Roman Stel’mashchuk, eds. Soiuz ukraïns’kykh profesiinykh muzyk u L’vovi: Materialy i dokumenty (Lviv 1997)

Hundorova, Tamara. ProIavlennia slova: Dyskursiia rann’oho ukraïns’koho modernizmu. Postmoderna interpretatsiia. (Lviv 1997)

Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. Ukrainian Futurism, 1914–1930: A Historical and Critical Study (Cambridge, Mass. 1997)

Kyianov’ska, Liuba. “Styl’ setsesiï v ukraïns’kii muzytsi pershoï tretyny 20-ho stolittia,” in Musica Galiciana: Kultura myzyczna Galicji w kontekście stosunków polsko-ukraińskich (od doby piastowsko-książęcej do roku 1945), ed Leszek Mazepa, vol 3 (Rzeszów 1999)

Pavlychko, Solomiia. Dyskurs modernizmu v ukraïns’kii literaturi (Kyiv 1997; revised ed 1999)

Chepelyk, Viktor. Ukraïns’kyi arkhitekturnyi modern (Kyiv 2000)

Shkandrij, Myroslav, ed. The Phenomenon of the Ukrainian Avant-Garde, 1910–35 (Winnipeg 2001)

Aheieva, Vira. Zhinochyi prostir: Feministychnyi dyskurs ukraïns’koho modernizmu (Kyiv 2003)

Makaryk, Irene Rima. Shakespeare and the Undiscovered Bourn: Les Kurbas, Ukrainian Modernism, and Early Soviet Cultural Politics (Toronto 2004)

Sviatoslav Hordynsky, Myroslav Shkandrij

[This article was updated in 2005.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1952.jpg)