Mazepa, Ivan

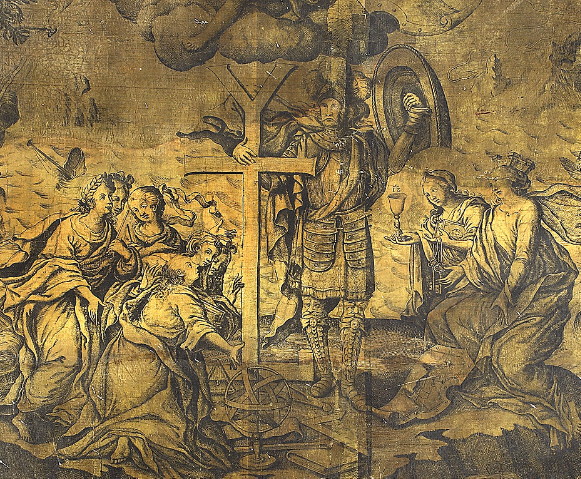

Mazepa, Ivan [Мазепа, Іван], b 20 March 1639 in Mazepyntsi, near Bila Tserkva, d 2 October 1709 in Bendery, Bessarabia. Hetman of Ukraine in 1687–1709; son of Stepan-Adam Mazepa and Maryna Mazepa. He studied at the Kyivan Mohyla College and at the Jesuit college in Warsaw. While a page at the court of Jan II Casimir Vasa in Warsaw, he was sent by the king to study in Holland. In 1656–9 he learned gunnery in Deventer and visited Germany, Italy, France, and the Low Countries. After his return to Warsaw Mazepa continued his service as a royal courtier, and in 1659–63 he was sent on various diplomatic missions to Ukraine. The legend of his affair with Madame Falbowska and his subsequent punishment by being tied to the back of a wild horse was first popularized by the Polish memorialist J. C. Pasek. Although it has no basis in fact, it has inspired a number of European Romantics, including Franz Liszt, Peter Tchaikovsky, George Byron, Victor Hugo, and Aleksandr Pushkin and led to a rather fanciful image of the Ukrainian hetman as a youth.

In 1663 Mazepa returned to Ukraine to help his ailing father. After his father’s death in 1665 he succeeded him as hereditary cupbearer of Chernihiv. In 1669 Mazepa entered the service of Hetman Petro Doroshenko as a squadron commander in the Hetman’s Guard, and later he served as Doroshenko’s chancellor. He took part in Doroshenko’s 1672 campaign against Poland in Galicia and served on diplomatic missions, including ones to the Crimea and Turkey (1673–4). During a mission in 1674 he was captured by the Zaporozhian otaman Ivan Sirko, who was forced to hand him over to Doroshenko’s rival in Left-Bank Ukraine, Ivan Samoilovych. Mazepa quickly gained the confidence of Samoilovych and Tsar Peter I, was made a ‘courtier of the hetman,’ and was sent on numerous missions to Moscow. Mazepa participated in the Chyhyryn campaigns, 1677–8. In 1682 he was appointed Samoilovych’s general osaul. He was elected the new hetman on 25 July 1687 by the Cossack council that deposed Samoilovych and concluded the disadvantageous Kolomak Articles with the tsar.

Mazepa’s political program had become evident during his service to Petro Doroshenko and Ivan Samoilovych. He was a firm supporter of a pan-Ukrainian Hetman state, and his main goal as hetman was to unite all Ukrainian territories in a unitary state that would be modeled on existing European states but would retain the features of the traditional Cossack order. Initially Mazepa believed that the Cossack Hetman state could coexist with Muscovy on the basis of the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654. Mazepa actively supported Muscovy’s wars with Turkey and the Crimean Khanate and sent his forces to help those of Peter I (see Russo-Turkish wars). Although the Treaty of Constantinople of 3 July 1700 did not extend Ukrainian dominion to the Black Sea, it temporarily secured Ukrainian lands from Turkish encroachment and Crimean Tatar incursions. Until 1708 Mazepa also supported Peter I in the first phase of his Great Northern War with Sweden, by providing the Muscovites with troops, munitions, money, and supplies in their effort to capture the Baltic lands. Mazepa’s participation in the war made it possible for him to take control of Right-Bank Ukraine in 1704, after Semen Palii’s Cossack revolt effectively weakened Polish authority there. Mazepa’s relations with Palii were not entirely positive, however. Mazepa did not share the Fastiv colonel’s radical social policies, and that difference gave rise to conflicts between them.

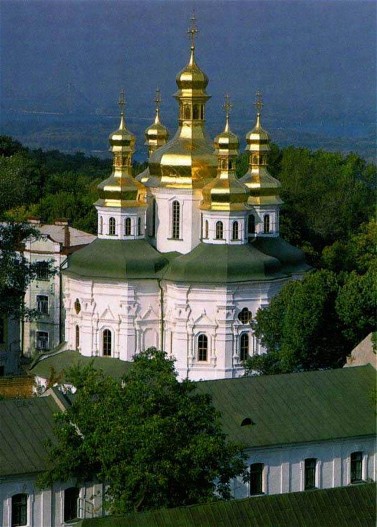

Mazepa contributed to the development of Ukraine’s economy, particularly its industry. He also supported Ukrainian scholarship (history in particular) and education (the transformation of the Kyivan Mohyla College into the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, the establishment of Chernihiv College). Under his hetmancy literature flourished (see Dymytrii Tuptalo, Stefan Yavorsky, Ioan Maksymovych, Teofan Prokopovych, and Yoasaf Krokovsky). Mazepa himself wrote some verse. He was a generous patron of painting and architecture, who funded many churches built in the Cossack baroque style in Kyiv, Chernihiv, Pereiaslav, Baturyn, Pryluky, and other towns. Mazepa was also a patron of the Orthodox church outside Ukraine. He funded the publication of the New Testament in Arabic in Aleppo in 1708, and he donated an Easter shroud and a pure gold chalice for the Tomb of the Lord in Jerusalem.

Although Mazepa was able to establish a new and loyal senior Cossack starshyna, he also faced considerable opposition from many members of the Cossack elite, and even open rebellion (see Petro Petryk, Vasyl Kochubei, and Ivan Iskra). Mazepa’s many attempts to secure the rights of the Cossacks as an estate (the universal of 1691), the burghers (a series of universals protecting their rights), and the peasantry (the universal of 28 November 1701 limiting corvée to two days a week) could not stem the growth of social discontent caused by endless wars, abuse of the population by Muscovite troops stationed in Ukraine, destruction, and increasing exploitation by the landowning starshyna. Mazepa’s alliance with Peter I also caused onerous responsibilities and losses to be inflicted on the population, in particular as a result of the Great Northern War and Muscovite exploitation in Ukraine. Consequently Mazepa was deprived of the popular support he needed at a critical juncture in Ukrainian history.

Peter I not only interfered in the Hetmanate’s internal affairs and mercilessly exploited the population in his belligerent pursuits, but embarked on a policy of annihilating Ukrainian autonomy and abolishing the Cossack order and privileges. When Peter’s intentions became clear, Mazepa, supported by most of his senior officers, began secret negotiations in 1706 with King Stanislaus I Leszczyński of Poland and then with Charles XII of Sweden, and forged with them an anti-Muscovite coalition in 1708. The actual terms of the alliance are unknown, but according to official Russian sources its chief goal was ‘that the Little Russian Cossack people be a separate principality and not subjects of a Muscovite state.’ Later the Zaporozhian Host joined the coalition, and on 28 March 1709 Mazepa, Otaman Kost Hordiienko, and Charles XII signed a treaty in which Charles agreed not to sign any peace with Moscow until Ukraine and the Zaporizhia were freed of Muscovite rule.

But the Russo-Swedish War of 1708–9, which was waged on Ukrainian territory, ended in defeat for the allies. Peter I’s forces captured Mazepa’s capital, Baturyn, together with its large armaments depot and artillery, massacred its 6,000 inhabitants, and succeeded in splitting Mazepa’s followers by engineering the election of Ivan Skoropadsky as a new hetman in Hlukhiv in November 1708. Muscovite military terror descended on those who remained loyal to Mazepa. Captured Zaporozhian Cossacks were brutally executed, the Zaporozhian Sich was destroyed, and many of Mazepa's followers (eg, Dmytro Maksymovych, Archimandrite Hedeon Odorsky) were executed or exiled to northern Muscovy. Mazepa’s efforts at organizing a broad anti-Muscovite front in Eastern Europe proved unsuccessful, and his and Charles XII’s defeat at the Battle of Poltava on 8 July 1709 sealed Ukraine's fate. Mazepa, Charles, and Kost Hordiienko, together with 3,000 followers, fled to Turkish-held territory. Broken by his defeat, old and ill, Mazepa died in Bendery, Moldavia. He was buried at Saint George’s Monastery in Galaţi, where his tomb was subsequently desecrated.

Peter I initially sought Mazepa’s extradition from Turkey. Having condemned Mazepa as a traitor he ordered the Russian and Ukrainian churches to anathematize him. Thereafter, imperial, both Russian and Soviet, propagandists and historians did their utmost to vilify the Ukrainian patriot and statesman. Although there have been controversial assessments of Mazepa, he has remained a symbol of Ukrainian independence. The period of his hetmancy has justifiably been known as the Mazepa renaissance.

Apart from the works by Western European and Russian authors mentioned above, the hetman’s life and legacy inspired works by Ukrainian writers and artists, such as Bohdan Lepky who dedicated a series of novels to Mazepa, and Yurii Illienko who directed the film Molytva za het’mana Mazepu (Prayer for Hetman Mazepa) in 2002.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Umanets, F. Getman Mazepa: Istoricheskaia monografiia (Saint Petersburg 1897)

Kostomarov, N. ‘I. Mazepa,' in Istoricheskiia monografii i issledovaniia, vol 6 (Saint Petersburg 1905); repr: UIZh, 1988, no. 8ff

Jensen, A. Mazepa: Historiska bilder från Ukraine och Karl XIIs dagar (Lund 1909)

Borschak, E.; Martel, R. Vie de Mazeppa (Paris 1931)

Andrusiak, M. Mazepa i Pravoberezhzha [sic] (Lviv 1938)

Smal’-Stots’kyi, R. (ed). Mazepa: Zbirnyk, 2 vols (Warsaw 1938–9)

Krupnyckyj, B. Hetman Mazepa und seine Zeit (1687–1709) (Leipzig 1942)

Het’man Ivan Mazepa. Pysannia (Cracow–Lviv 1943)

Manning, C.A. Hetman of Ukraine Ivan Mazeppa (New York 1957)

Nordmann, C.J. Charles XII et l'Ukraine de Mazepa (Paris 1958)

Ohloblyn, O. Het'man Ivan Mazepa ta ioho doba (New York, Paris, and Toronto 1960)

Kentrschynskyj, B. Mazepa (Stockholm 1962)

Mackiw, T. ‘Mazepa im Lichte der zeitgenössischen deutschen Quellen,’ ZNTSh, 174 (1963)

Mackiw, T. Prince Mazepa, Hetman of Ukraine in Contemporary English Publications, 1687–1709 (Chicago 1967)

Babinski, H. The Mazeppa Legend in European Romanticism (New York 1974)

Subtelny, O. (ed). On the Eve of Poltava: The Letters of Mazepa to Adam Sieniawski, 1704–1708 (New York 1975)

—The Mazepists: Ukrainian Separatism in the Early Eighteenth Century (New York 1981)

Mackiw, T. English Reports on Mazepa: Hetman of Ukraine and Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, 1687–1709 (New York–Munich–Toronto 1983)

Mats'kiv, T. Het’man Ivan Mazepa v zakhidn’oevropeis’kykh dzherelakh, 1687–1709 (Munich 1988)

Ivanchenko, Iu. (ed). Mazepa: Zbirnyk (Kyiv 1993)

Bondarenko, L. (ed). Ivan Mazepa i Moskva: Istorychni rozvidky i statti (Kyiv 1994)

Stanislavs’kyi, Viacheslav (ed). Z epistoliarnoï spadshchyny het’mana Ivana Mazepy (Kyiv 1996)

Universaly Ivana Mazepy 1687–1709 (Kyiv–Lviv 2002)

Stanislavs'kyi, Viacheslav (ed). Lysty Ivana Mazepy: tom 1, 1687–1691 (Kyiv 2002)

Siedina, G. (ed). Mazepa e i suoi successori. Storia, cultura, societa/Mazepa and His Followers: History, Culture, Society (Alessandria 2004)

Pavlenko, S. Ivan Mazepa iak budivnychyi ukraïns’koï kul’tury (Kyiv 2005)

Tairova-Iakovleva, Tatiana. Getman Ivan Mazzepa: Dokumenty iz arkhivnykh sobranii Sankt-Peterburga, vyp. 1: 1687–1705 gg. (Saint Petersburg 2007)

———. Mazepa (Moscow 2007)

Rendiuk, Teofil. Het'man Ivan Mazepa: Vidomyi i nevidomyi... (Kyiv 2010)

Stanislavs'kyi, Viacheslav (ed). Lysty Ivana Mazepy: tom 1, 1691–1700 (Kyiv 2010)

Skochylias, Ihor (ed). Ivan Mazepa i mazepyntsi: Istoriia ta kul'tura Ukraïny ostannioi tretyny XVII–pochatku XVIII st. (Lviv 2011)

Kentrzhyns'kyi, Bohdan. Mazepa (Kyiv 2013)

Tairova-Iakovleva, Tetiana. Ivan Mazepa i Rosiis'ka imperiia: Istoriia “zrady” (Kyiv 2013)

Tairova-Yakovleva, T. Ivan Mazepa and the Russian Empire (Montreal, Kingston, Edmonton, and Toronto 2020)

Oleksander Ohloblyn

[This article was updated in 2008.]

.jpg)