Lviv Sobor of 1946

Lviv Sobor of 1946 (Львівський собор; Lvivskyi sobor). The central formal event in the annexation of Halych metropoly of the Greek Catholic church by the Moscow patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox church following the Soviet occupation of Western Ukraine. Held on 8–10 March 1946 in Saint George's Cathedral in Lviv, the sobor was the culmination of a lengthy campaign against the church. Some preparatory work—particularly the probing of political, ideological, and personality differences within the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church—had been undertaken by the Soviet authorities during their first occupation of Galicia in 1939–41. The cohesiveness of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church structure, however, and the exposed strategic location of Galicia on a frontier with German-occupied territories made any campaign of ‘reunification’ with the Russian Orthodox church politically untenable. Postwar conditions were considerably different. The death of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky (1 November 1944), the spiritual leader of Ukrainian Catholics, had left the church without a strong figurehead, and the extension of Soviet influence over the entire Eastern bloc had diminished Galicia’s relative strategic significance. Moreover, the Soviet authorities could conveniently employ charges of ‘treason to the Fatherland’ against the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church because of the moral support it had lent to anti-Soviet Ukrainian groups during the German occupation of Ukraine. Thus the stage was set for a campaign against the church which ultimately led to its formal liquidation in 1946 at the Lviv Sobor.

The Lviv Sobor set the stage for similar actions in Transcarpathia (1949) and Czechoslovakia (1950). The case of Halych metropoly, however, was of particular significance, partly because of the sheer size of the metropoly, with (according to 1938 statistics) 2,354 diocesan and monastic priests, at least 315 monks, 929 nuns, and 3.4 million faithful. More significant was the potential political challenge the church represented because of its traditional role as a bulwark of Ukrainian national consciousness in the newly annexed region.

Events immediately following the Soviet occupation seemed to indicate that a modus vivendi might be reached between the church and the Soviet authorities. An elaborate funeral was allowed for Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky after his death on 1 November 1944, and the Soviet press noted the installation of Yosyf Slipy as the new metropolitan of Halych. In turn, a Ukrainian Catholic delegation went to Moscow in December 1944 for discussions with Soviet officials about the normalization of the church’s status, and also paid a courtesy visit to the Moscow patriarchate. The situation had changed dramatically, however, by the early spring of 1945. In the wake of the church’s refusal to partake in Soviet propaganda efforts, particularly those denouncing the Ukrainian nationalist movement, the official press published articles and pamphlets (notably those written by the publicist Yaroslav Halan) which attacked the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church and accused it of subversive acts. Soon afterwards (11 April 1945) Metropolitan Slipy and Bishops Hryhorii Khomyshyn, Mykola Charnetsky, Nykyta Budka, and Ivan Liatyshevsky were arrested and later (in June 1946) they were sentenced to lengthy terms in forced labor camps for their purported ‘traitorous activities and collaboration with the German occupation forces.’ At the same time the Soviet authorities took measures to block the election by the Ukrainian Catholic clergy of capitular vicars to administer the vacant sees, thus rendering the church leaderless.

A government-approved ‘Sponsoring Group for the Re-Union of the Greek Catholic Church with the Russian Orthodox Church’ emerged publicly on 28 May 1945 and proclaimed itself as the only legally constituted leadership of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church. In spite of a letter of protest from some 300 Ukrainian Catholic clergymen, the sponsoring group was officially given an exclusive jurisdiction over the church by Soviet Ukrainian authorities on 18 June 1945. Likewise, the newly appointed Russian Orthodox bishop for Western Ukraine, Makarii (Oksiiuk), was instructed to ‘assist’ the group in its efforts. The Sponsoring Group consisted of three priests, representing each of the metropoly’s eparchies: Havryil Kostelnyk (the Lviv-based chairman and a well-known critic of the Vatican’s policy toward the Uniate church), Mykhailo I. Melnyk (vicar-general of Peremyshl eparchy), and A. Pelvetsky (a dean in Stanyslaviv eparchy). The three priests led an intensive campaign to convince the Galician clergy of the benefits of ‘reunification,’ focusing mainly on the political realities of living under the new Soviet regime and on dissatisfaction with the Latinizing elements within the Uniate church. Priests who were not convinced by these arguments were subjected to less subtle persuasion by Soviet security officials, through direct threats, deportation, or summary sentences to terms in forced labor camps. By March 1946 a total of 986 priests (over 50percent of the clergy) had been convinced to support the ‘reunification.’ Of the remaining ‘recalcitrant’ priests in Galicia, only 281 were reported to be still at large; others either had been imprisoned or deported or had gone into hiding.

With overt public resistance from the clergy now unlikely, the road was almost clear for completion of the ‘reunification’ process. The one remaining obstacle was the canonic need for the participation of bishops in convening and conducting a church sobor. Since none of the imprisoned Ukrainian Catholic bishops would succumb to Soviet pressure to convert to Orthodoxy, the Moscow patriarchate undertook the extraordinary action of ordaining two of the Sponsoring Group leaders, A. Pelvetsky and Mykhailo I. Melnyk, as Orthodox bishops in February 1946.

The sobor itself was a carefully staged showpiece. Set to coincide with the 350th anniversary of the Church Union of Berestia, which had given birth to the Uniate church, its proceedings were covered by Soviet film crews and reporters. A total of 216 clerical and 19 lay delegates were ‘invited’ to participate. The agenda of the proceedings was not announced until the commencement of the sobor, following the pronouncement by the leaders of the Sponsoring Group that they had appointed themselves as the presidium of the gathering. The first day of the session consisted of the Sponsoring Group’s reports and its presentation of a draft resolution abolishing the Church Union of Berestia and ‘returning’ the Halych metropoly to the Russian Orthodox church. With no further discussion, the resolution was adopted ‘unanimously’ by a show of hands. Only then did Kostelnyk reveal to the delegates that A. Pelvetsky and Mykhailo I. Melnyk had been ordained as Orthodox bishops. The remaining two days of the sobor were taken up with ceremonial aspects of the ‘re-union’, the approval of earlier-prepared political messages to state authorities, and a plea to the clergy and faithful of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church to accept the new state of affairs.

The sobor was followed by a wave of repression against those priests and monks who had refused to accept the ‘re-union’. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic church, as such, became an illegal, catacomb organization. Extensive popular resistance was demonstrated against the new situation as many parishes refused to allow Russian Orthodox clergymen into their churches. In September 1948 the Sponsoring Group leader, Havryil Kostelnyk, was assassinated in Lviv, allegedly by a ‘Vatican-nationalist’ agent; in fact, all indications are that this act was masterminded by the Soviet authorities. The leading polemicist against the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church, Yaroslav Halan, was killed by Ukrainian nationalists in October 1949. In 1972 the ‘re-union’ of the Greek Catholic church was ratified by the local sobor of the Russian Orthodox church. In the West the uncanonical nature of the Lviv Sobor was noted, and the liquidation of the church roundly condemned by Catholic authorities, most notably by the papal encyclical The Oriental Churches of 15 December 1958 and, more recently, at the meeting of the synod of the Ukrainian Catholic bishops in Rome in 1980. On 1 December 1989 the Ukrainian Catholic church was legalized by the authorities of the Ukrainian SSR.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

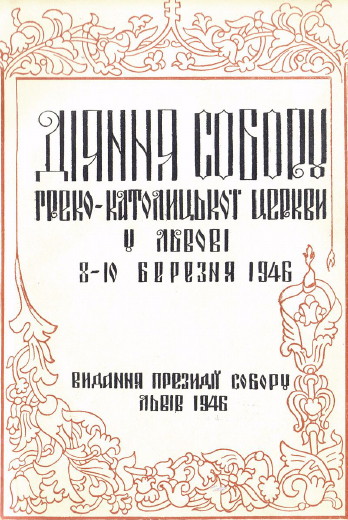

Diiannia soboru hreko-katolyts'koï tserkvy v m. L'vovi 8–10 bereznia 1946 roku (Lviv 1946)

Hryn'okh, I. ‘Znyshchennia Ukraïns'koï Katolyts’koï Tserkvy rosiis'ko-bol'shevyts'kym rezhymom,’ Bohosloviia, XlIV, 1–4 (1980)

Moiseyev, F. The Lvov Church Council: Documents and Materials, 1946–1981 (Moscow 1983)

Bociurkiw, Bohdan. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and the Soviet State (1939–1950) (Edmonton–Toronto 1996)

Bociurkiw, Bohdan. Ukrains'ka Hreko-Katolyts'ka Tserkva i Radians'ka derzhava (1939–1950) (Lviv 2005)

Bohdan R. Bociurkiw

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]