Landscape art

Landscape art. The depiction of natural scenery. In Ukrainian art highly conventionalized landscape elements were used in icons (eg, The Transfiguration [14th century] in the Church of the Mother of God in Busovysko, near Turka, Galicia). Architectural settings became part of the separately enclosed scenes in icons illustrating the lives of saints (eg, in the icon of Saints Cosmas and Damian [15th century] from Tylych in the Lemko region). During the Renaissance landscapes in icons became less schematized and began looking more like the surrounding Ukrainian countryside (eg, in The Dream of Jacob [1650] in the iconostasis of the Church of the Holy Ghost in Drohobych). Architecture and local scenery were important elements in the icons of Ivan Rutkovych (Road to Emmaus [1697–9] in the iconostasis of the church in Skvariava Nova, near Zhovkva, Galicia) and Yov Kondzelevych (the landscape on The Dormition in the Bilostok Monastery [late 17th century]). Landscapes also appeared as backgrounds to portraits (portrait of Yevdokiia Zhuravko [18th century]).

Some of the earliest landscapes were settings for religious engravings. At first they were variations on landscapes borrowed from Western European models, but later, local elements emerged. In 1669 Master Illia depicted the Dnipro River in his engraving The Coming of Iconographers from Constantinople. Similar engravings by Leontii Tarasevych showed an even greater preoccupation with local scenery. In 1674 Nykodym Zubrytsky engraved the siege of the Pochaiv Monastery, and in 1699 Dionisii Sinkevych engraved the architectural ensemble of the Krekhiv Monastery; both were from a bird's-eye view. Depictions of churches and secular buildings appeared in the engraved theses produced in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. Hryhorii K. Levytsky engraved a realistic panorama of the land and architecture for the thesis dedicated to Metropolitan Rafail Zaborovsky (1739). Ifika iieropolitika (1712) contained Zubrytsky's engraving of a windmill on a river bank.

In the 18th century, landscapes gained greater prominence in religious pictures (eg, the depiction of Mount Sinai in the mural in the west wall of Saint George's Church in Drohobych). One of the earliest attempts to convey the local scenery was made by M. Terensky (the town of Dubets as seen through a window in his Krasytsky Family Portrait [1753]). Vasyl Hryhorovych-Barsky popularized landscape art through his drawings of his travels (1723–47) in Europe and the Near East.

At the beginning of the 19th century landscapes became an integral part of icon compositions. In Mary and Elizabeth in the iconostasis of the church in Sulymivka, Poltava gubernia (ca 1830), the foliage and trees dominate the composition.

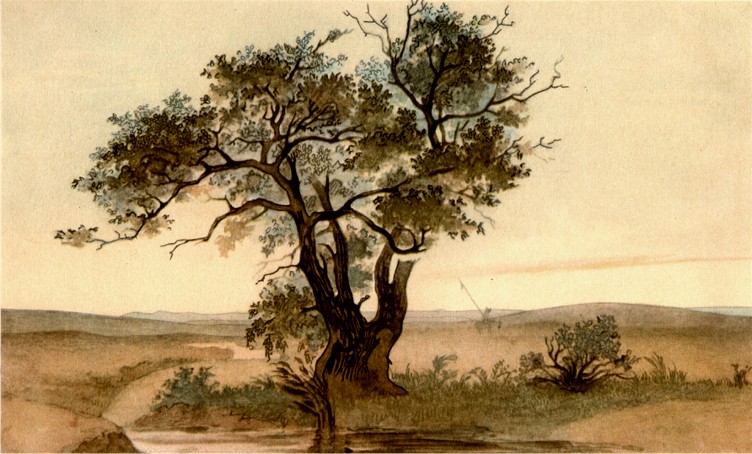

Landscape painting did not, however, become an independent genre in Ukrainian art until the 19th century. Romanticism inspired artists to record faithfully the pastoral scenery of thatched-roof cottages and the surrounding countryside. Among them were Ivan Soshenko (The Ros River near Bila Tserkva), Taras Shevchenko, and Vasilii Shternberg (View of [the] Podil [District] in Kyiv, 1837). Shevchenko painted watercolor landscapes of interesting architecture when he worked for the Kyiv Archeographic Commission. He did two landscapes (Kyiv and The Vydubychi Monastery) for his series of etchings on Ukrainian topics called Zhivopisnaia Ukraina (1844). In exile he depicted the surrounding countryside in numerous drawings and watercolors; they included landscapes of the Aral Sea coast (1848–9), the Mangishlak Peninsula (1851), and the area around the Novopetrovsk Fortress (1853–7).

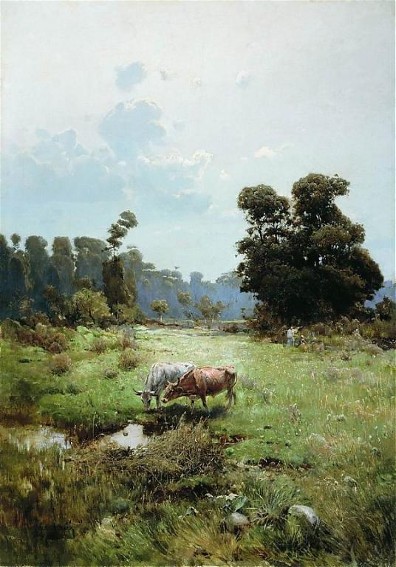

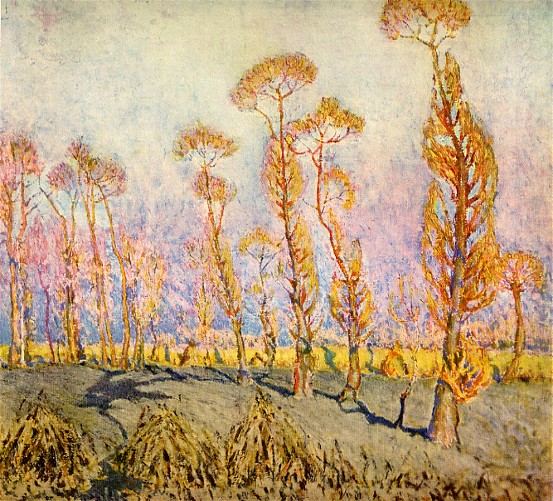

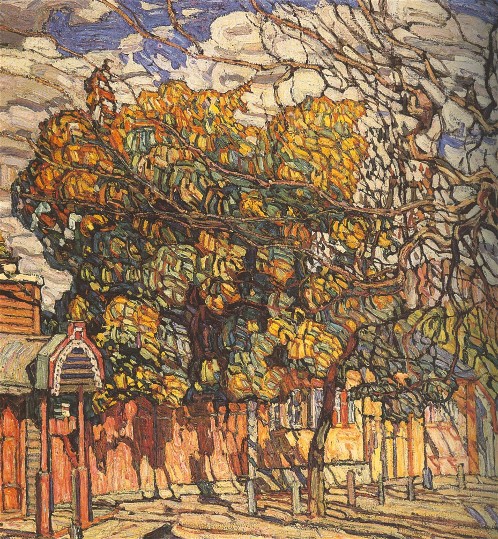

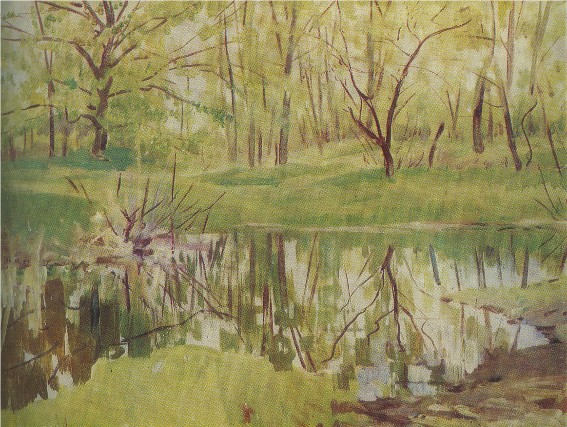

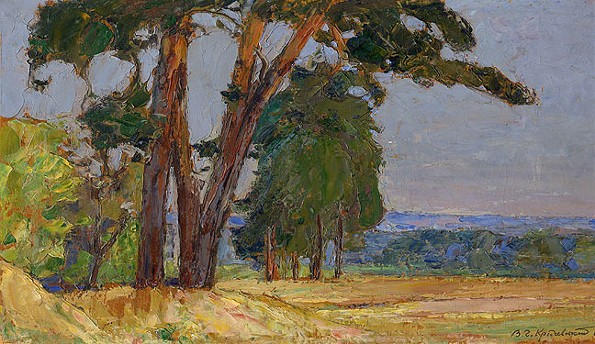

With time two types of landscape art developed, the poetic and the epic. Among the 19th-century artists who devoted much of their work to Ukrainian landscapes were two artists of non-Ukrainian origin, Ivan Aivazovsky, who is famous for his marine paintings, and Arkhyp Kuindzhi, who painted Romantic moonlit scenes. Other Ukrainian artists who devoted their efforts to landscape painting were Serhii Vasylkivsky, Ivan Pokhytonov, Mykhailo S. Tkachenko, and Serhii Svitoslavsky. In the early 20th century Petro Levchenko painted intimate lyrical views in impressionist colors capturing the fleeting effects of light in both urban and rural scenes (Fountain near the Golden Gate and Cottage, Zmiiv, 1915). Vasyl H. Krychevsky and Abram Manevich also worked in the impressionist manner. Symbolism was dominant in the fantasy landscapes of Yukhym Mykhailiv (Music of the Stars, 1920s). Oleksander Bohomazov painted landscapes utilizing elements of cubism (Cityscape, Kyiv, 1912–13) and cobofuturism (Tram, 1914).

In Western Ukraine Ivan Trush painted idyllic sunsets, ordinary fields, and panoramic views (The Dnipro, 1910) only slightly influenced by impressionist colors, and Olena Kulchytska depicted informal scenes using an impressionist palette (Willows, 1907). Oleksa Novakivsky became known for his expressionist views of the countryside (Mount Grehit, 1934) and urban scenes (numerous views of Saint George's Cathedral in Lviv, such as St. George's Cathedral, 1921–2). Landscape painting was also prominent in the work of the Transcarpathian artists Yosyp Bokshai (First Frost, 1927), Emilian Hrabovsky (Thaw, 1921), and Zoltan Sholtes (Wooden Church, 1939).

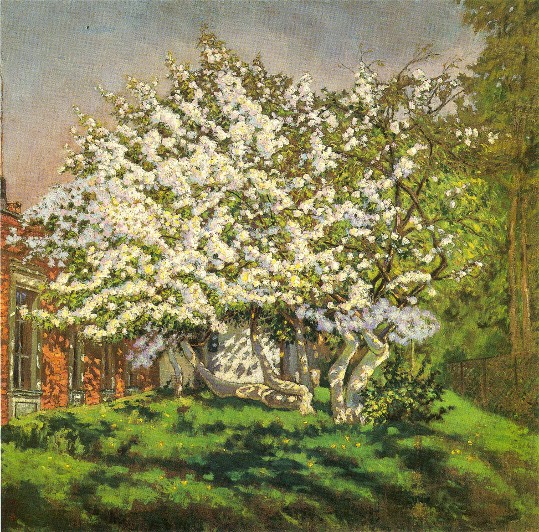

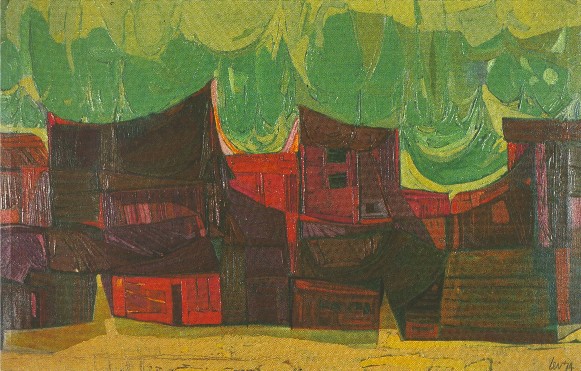

In the 1930s, after socialist realism was imposed as the only sanctioned artistic method in the USSR, landscape painting in Soviet Ukraine was limited to views of collective farms (eg, Hryhorii Svitlytsky's Collective Farm in Blossom [1935] and Mykola Burachek's Road to a Collective Farm [1938]) and industrial sites. Pure landscape painting was revived in Ukraine after the Second World War through the influence of Western Ukrainian artists, such as Yosyp Bokshai, Roman Selsky, and Vitold Manastyrsky. But landscapes were painted in a naturalist manner in keeping with socialist realism. During Nikita Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’ landscape painting regained some of its lost prominence largely as a result of efforts by Oleksii Shovkunenko (Flood in Koncha Zaspa, 1954), Mykola Hlushchenko (Winter Morning, 1958), Serhii Shyshko (Carpathian Landscape, 1951), and Dmitrii Shavykin (Evening on the Dnipro River, 1957) in Kyiv; Selsky and his wife, Margit Selska, in Lviv; and Bokshai, Antin Kashshai, and Fedir Manailo in Uzhhorod.

In Lviv Roman Selsky popularized Carpathian landscapes (eg, Chornohora, 1968), seascapes, and views of Crimea, often using natural scenery to create constructs of color and form (Thicket, 1968). Vitold Manastyrsky painted landscapes characterized by rhythmic patterns of flat pigment (eg, Under the Mountain Sokil, 1962). Hryhorii Smolsky, Oleksa Shatkivsky, S. Koropchak, and D. Dovboshynsky have painted landscapes in a variety of figurative styles. Landscapes have been particularly prominent in the work of Volodymyr Patyk, who paints with great spontaneity and expressive hues (Summer, 1972), and Liubomyr Medvid, whose monochromatic, highly realistic views, with forms reduced to their essentials, are a departure from socialist realism (Heat Wave, 1969).

In Kyiv Tetiana Yablonska painted panoramic views of the land in the 1960s (Nameless Heights, 1969) and eventually turned to landscape studies in contrasts of light in the manner of the French impressionists (Our Beautiful Kyiv, 1986). Realistic landscapes depicting the beauty of the Ukrainian countryside have dominated in the work of Vasyl Nepyipyvo. The Kyiv artists H. Havrylenko, Ya. Levych, A. Lymariev, and Moisei Vainshtein devoted considerable time to landscapes that did not conform to socialist realism, as did Yevhen Yehorov, O. Voloshynov, V. Basanets, Volodymyr Strelnikov, and Volodymyr Tsiupko in Odesa. Both Strelnikov (By the White House, 1979) and Tsiupko (Boats, 1978) have painted landscapes bordering on abstraction and abstractions inspired by landscapes. There are folk-art elements in Volodymyr Padun's landscapes of rural Ukraine around Dnipropetrovsk (Old Village, 1979). Unusual but realistic landscapes, as well as nightmarish, surrealistic scenes of desolate places, have been created by Ivan Marchuk, who works with a weblike technique (Night in the Steppe, 1984). Ye. Hordiiets (Pink Rocks, 1986) paints meticulous photorealist landscapes that often contain elements of the fantastic, as do the works of V. Pasyvenko and Dmytro Stetsko. Expressionism prevails in the landscapes of Mykhailo Popov and Yurii Lutskevych.

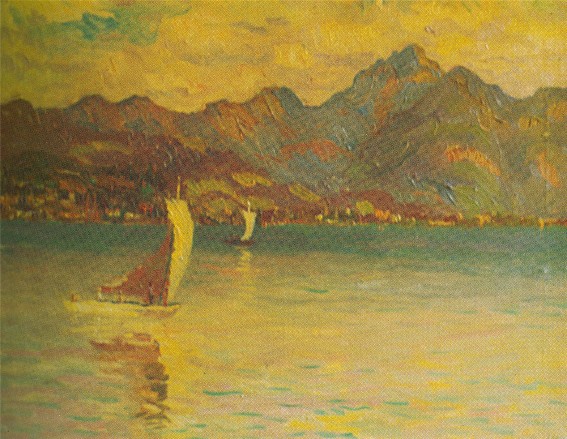

Of the Ukrainian landscape artists who worked outside their homeland, the most prominent was Oleksa Hryshchenko (Alexis Gritchenko), who achieved recognition in France for his landscapes and seascapes (eg, Toulon [1925]), painted mostly in an expressionist manner. Mykola Krychevsky, who worked in Paris from 1929, specialized in sensitive watercolor views of the city. Andrii Solohub has concentrated on watercolor landscapes of Paris and Istanbul, and Zoia Lisovska has specialized in gouaches of landscapes of the Swiss Alps. Expressionistic glimpses of France alongside those of his native Carpathian scenery constitute the major portion of the work of Omelian Mazuryk, who worked in Paris from 1968 (Villaret, 1971; Carpathian Church, 1985).

In the United States vibrant colors and expressive brush strokes have been typical of the work of Mykhailo Moroz (Bar Harbor, Maine), Mykola Nedilko (Boats, 1965), and Liuboslav Hutsaliuk (Architectural Landscape). Other artists who have painted landscapes there include Vasyl V. Krychevsky, Myroslav Radysh, K. Krychevska-Rosandych, and M. Harasovska-Dachyshyn. Of the artists who emigrated to Canada Myron Levytsky has painted numerous semiabstract landscapes (Spanish Town, 1965), Halyna Novakivska has experimented with textural effects (Along the Road), and Mariia Styranka has concentrated on delicate watercolor views (Winter, 1988). William Kurelek, the most famous Canadian artist of Ukrainian origin, depicted the Canadian landscape from coast to coast in a highly personal, realistic manner often bordering on the primitive (Fields, 1976). William Lobchuk, Don Proch, Peter Shostak, and Dmytro Stryjek have also painted Canadian landscapes.

Daria Zelska-Darewych

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)