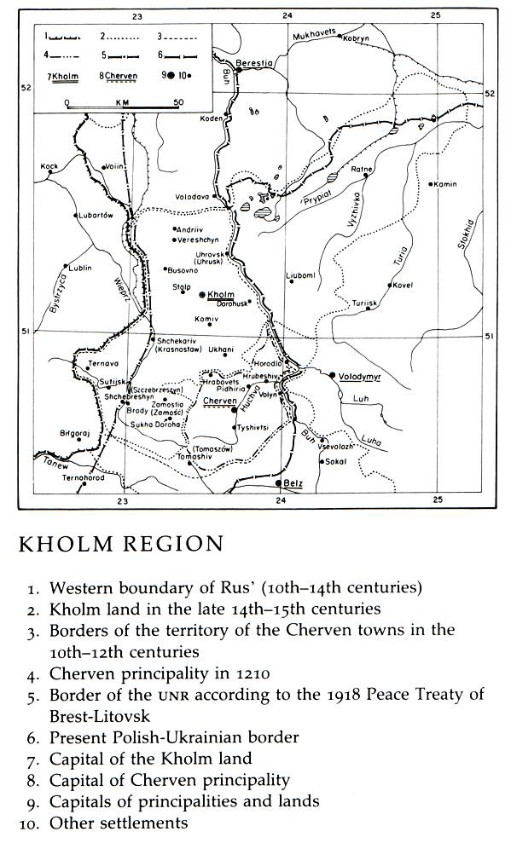

Kholm region

Kholm region [Холмщина; Kholmshchyna; Polish: Chełmszczyzna]. (Map: Kholm region.) A historical-geographic region west of the Buh River, bordering on the Polish Lublin region in the west, Volhynia in the east, Podlachia in the north, and Galicia in the south. The boundary between Siedlce and Lublin gubernias of the Russian Empire can be taken as the boundary between the Kholm region (Kholm, Hrubeshiv, Krasnystaw, Tomaszów Lubelski, Zamość, and Biłgoraj counties) and Podlachia (Biała Podlaska, Volodava, Konstantyniv, and Radzyń Podlaski counties). In the interwar period the Kholm region within Lublin voivodeship had an area of 7,270 sq km. The name of the region, which has also been called Kholm Rus’ (Холмська Русь; Kholmska Rus'), the Transbuh region (Забужжя; Zabuzhia), and Transbuh Rus’ (Забузька Русь; Zabuzka Rus'), has often been extended to include Podlachia, because the latter was part of Kholm eparchy and (from 1912 to 1917) Kholm gubernia; except for northern Podlachia, which was part of Bielsk Podlaski county in Hrodna gubernia, the two regions have shared a common history since 1795.

Because it was a borderland, the Kholm region did not develop strong ties with the rest of Ukraine's territories, and until the 20th century its Ukrainian population had a relatively weak sense of national identity. The reign of Prince Danylo Romanovych of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia was the exception: being on the periphery of the Mongol invasion, the region enjoyed relative peace and prosperity, and Danylo made Kholm, its major city, his capital. Its proximity to Poland, however, made the region susceptible to Polish influences and facilitated its Polonization, beginning in the 14th century. Thereafter the history of both the Kholm region and Podlachia unfolded in a manner that was unique for Ukraine's lands, particularly in the religious sphere. Since 1921 they have belonged to Poland; from 1975 they constituted most of Chełm, Zamość, and Biała Podlaska voivodeships and the southern part of Białystok voivodeship. Since 1999 almost the entire Kholm region has been contained within the borders of Lublin voivodeship. After the Second World War most of the Ukrainian population was forcibly resettled by the Polish authorities (see Operation Wisła), and few Ukrainians live there today.

Physical geography. Most of the Kholm region lies in the western part of the Volhynia-Kholm Upland. Its gently undulating plain has an average altitude of 200–250 m and is built on a chalk foundation overlain with Tertiary strata, loess, and fertile soils (chornozems around Hrubeshiv). The region's small northern and northeastern parts lie in the medium-fertile Podlachia Lowland into which the descent (20–40 m) from the upland forms a distinct step. The southwest lies in the less fertile Sian Lowland. The rivers are part of the large Vistula River Basin; they include the Buh River with its tributaries the Uherka River and Huchva River, the Vepr River (Wieprz River) with the Bystrzyca River, and the Sian River's tributary, the Tanew River.

The region's climate is transitional between continental and oceanic. Winters are mild: in Kholm the median January temperature is –4.4°C. Summers are temperate: in Kholm the median July temperature is 18.5°C. The average annual temperature is 7.4°C. In neighboring Lublin there are 137 clear days per year and the annual precipitation is 546 mm, mainly in summer (250 mm). Almost all of the region belongs to the central-European mixed-forest zone. The eastern limit of the beech, fir, larch, and hornbeam and northwestern limit of the spruce run through it and Podlachia. At one time large forests covered the southwest. The region's soils are of the sandy (20 percent), loess (20 percent), chornozem (10 percent), loam (12 percent), peat-and-bog (16 percent), and pine-forest (15 percent) variety.

History

To 1815. The Kholm region has been inhabited since the Upper Paleolithic Period. In the early medieval period it was settled by the East Slavic Dulibians. From the second half of the 10th century it was ruled by the Volhynian princes of Kyivan Rus’ (see Cherven towns), and from the 13th century to 1340, by the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Its southern part constituted the historical Belz land. In the 14th century territorial wars for control of the region raged. It was held by Lithuania (1340–77) and Hungary (1377–87) before Poland consolidated its four-century rule there. In the 15th century almost all of the region was part of the Kholm land, which was divided into Kholm and Krasnystaw counties; it was governed from Kholm by a castellan appointed by the palatine of Rus’ voivodeship in Lviv. In 1648, during the Cossack-Polish War, the army of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky captured Kholm and Zamość and briefly held the Kholm region and Podlachia. In the 1650s and in 1704–10 Polish-Swedish battles took place there.

Under Polish rule the region's upper social strata succumbed to Polonization, which was bolstered by the influx of Polish colonists there and, in even greater numbers, in Podlachia. The Uniate church played a leading role in the region's cultural and educational life, beginning in the 17th century. The Kholm Uniate brotherhood and Basilian monks ran church schools; Bishop Metodii Terletsky founded a Uniate gymnasium in Kholm in 1639; and Bishop Maksymiliian Ryllo founded a Uniate seminary there in 1760. After the Third Partition of Poland in 1795, the Kholm region and Podlachia were annexed by Austria. From 1809 to 1814 they were part of the Napoleonic Grand Duchy of Warsaw; from 1815 to 1832, the Congress Kingdom of Poland; and from 1832 to 1917, the Russian Empire.

1815–1914. As part of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, the Kholm region and Podlachia were governed by Poles, and linguistic and religious Polonization increased. The Greek Catholic church was the only bulwark against complete assimilation. The region's nobles and magnates of Ukrainian descent had long been Polonized, however, and only the Ukrainian peasants remained loyal to the Uniate church and its clergy. Consequently even the Uniate church was unable to withstand the pressures of Romanization, and its clergy modified its structure by introducing chapters (see Canon), corrupted its ritual with such Roman trappings as organ music and monstrances, had iconostases removed, and delivered sermons in Polish. Thus the Uniate church in the Kholm region came to resemble the Roman Catholic church more than it did its counterpart in Galicia. Unlike the Galician clergy, few priests in the Kholm region and Podlachia had a higher education. Some spoke only Polish and did not know Church Slavonic, and they and their families regarded themselves as Poles. The failure of the Polish Insurrection of 1830–1 did not diminish Polish influence in the Kholm region and Podlachia, for the laws, official language, and administration in Russian-ruled Poland remained Polish. In 1839 the Uniate church was outlawed in the Russian Empire except in the Kholm region and Podlachia; there it continued to be tolerated but was closely supervised by the Russian viceroy in Warsaw, who influenced the nomination of bishops. At the same time, the church was able to retain some measure of Ukrainianness because of the presence of Galician-born priests there and because the metropolitan of Halych still had some say in the election of its bishops, even after Kholm eparchy was subordinated directly to the Vatican in 1830. The position of the church deteriorated after the defeat of the Polish Insurrection of 1863–4, which some local Uniate clergy supported and many priests' sons joined. The tsarist regime in Poland became more repressive, replaced Polish with Russian as the language of government and education, and brought many Russian bureaucrats and colonists into the region. To counteract Polish influence, in 1875 it abolished the Uniate church there, incorporating its 120 parishes into the new Kholm-Warsaw Orthodox eparchy. Around 100,000 of the Uniate faithful, particularly in Podlachia, refused to become Orthodox, and the tsarist authorities resorted to police and military violence, mass arrests, exile to Siberia, and even killing to suppress religious opposition. Only 59 of 214 Uniate clergy embraced the Orthodox faith; 74 others were exiled, and 66 were expelled to Galicia. At the same time, some Greek Catholic clergy from Galicia voluntarily converted and became Orthodox parish priests in the region, and many teachers from central Ukraine moved there and disseminated Ukrainian populist ideas among the peasantry. (See History of the Ukrainian church.)

Religious and ethnic relations in the Kholm region changed during the Russian Revolution of 1905, when Tsar Nicholas II issued an ukase on religious tolerance. Because the Uniate church was still outlawed, 170,000 of 450,000 ‘Orthodox’ converted to Roman Catholicism by 1908; many peasants were blackmailed and coerced by Polish landowners to do so. This conversion resulted in another upsurge of Polonization, particularly among the younger people. As a result the region's population was split into three groups: the nationally conscious Ukrainian-speaking Orthodox, the ethnic Polish Roman Catholics, and the Ukrainian-speaking converts, who by and large lacked a clear sense of national identity and were contemptuously called Kalakuty or ‘Pereketsi’ (turncoats) by the first group.

Alarmed by the conversions, the Russian Holy Synod created a separate Orthodox Kholm eparchy under Bishop Evlogii Georgievsky. To counteract Catholicism and Polonization, Georgievsky allowed the use of certain local liturgical customs and sermons in Ukrainian. At the turn of the 20th century the state of education in the Kholm region was better than in the central and eastern regions of Ukraine. A relatively dense network of elementary schools was in place and teachers were trained at pedagogical seminaries in Kholm and Biała Podlaska and the Kholm Theological Seminary. After the Revolution of 1905 the Ukrainian national movement found adherents among many of these teachers. From 1905 O. Spolitak and Kost Losky published several popular booklets and one issue of the confiscated newspaper Buh in Hrubeshiv. The Popular Enlightenment Society of Kholm Rus’ published books, the Russian and Ukrainian weekly Bratska besida (ed M. Kobryn), and the popular Kholmskii narodnyi kalendar. The Kholm Orthodox Brotherhood (est 1885) published the daily Kholmskaia Rus’ (1912–17).

To undermine Polish influence, local Orthodox circles (particularly the Kholm Brotherhood) proposed that the Kholm region become a separate gubernia. After many public hearings, written submissions, and debates in the Russian State Duma, where the gubernial project was opposed not only by the Polish caucus but also by the deputies of other national minorities (except the Ukrainians), the Kadets, and the socialists, the bill creating Kholm gubernia was passed and enacted by the tsar on 23 June 1912. The gubernia was formed out of the Ukrainian-populated parts of Lublin and Siedlce gubernias; its borders were delineated on the basis of Vladimir Frantsev's ethnographic maps. It was placed under the direct jurisdiction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Saint Petersburg, but its school system came under the supervision of the Kyiv school superintendent. The outbreak of the First World War prevented the law from being fully implemented.

1915–19. In August 1915 the Kholm region and Podlachia became a theater of war. Having already deported all German colonists into the Russian hinterland, before its retreat the Russian army conducted a mass evacuation of the region's population. Fearful of Polish persecution if they remained, almost all Russians and Ukrainians left voluntarily. Only the Poles and practically all the Kalakuty stayed behind. During its retreat the Russian army burned down almost all the Ukrainian villages. After the retreat only 25,000 Ukrainians remained—15,000 in the Kholm region and 10,000 in Podlachia.

Under the Austrian occupation, Ukrainian cultural and educational activity in the Kholm region was ruled out because of the small Ukrainian population and because the Austrian authorities, who were influenced by the Poles, forbade it. In Podlachia, however, which was occupied by the Germans, the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine was allowed to open Ukrainian schools in early 1917, and the Ukrainian Hromada in Biała Podlaska was allowed to publish the newspaper Ridne slovo (1917–19).

The 300,000 evacuees from the Kholm region and Podlachia suffered severe hardships during their chaotic evacuation to the east. Most of them lost their belongings on the way, and many succumbed to disease. Eventually the tsarist authorities set up relief committees to help them resettle in the Volga region or in Central Asia. Most worked as farm laborers; because of their agrarian skills, they managed to live reasonably well. Being displaced among Russians made the refugees aware that they were not Russian. The Revolution of 1917 and the creation of the Central Rada in Kyiv had an even greater impact on their national consciousness. In spring 1917 they held a number of local congresses in various places of the empire and chose 276 delegates to the All-People's Congress of the Kholm Region. Held in Kyiv on 7–12 September 1917, the congress resolved that the people of the Kholm region were Ukrainian and should be part of Ukraine and elected a Kholm Gubernia Executive Committee whose members—Onoprii Vasylenko, Rev Antonii Mateiuk, Tymish Olesiiuk, A. Duda, Semen Liubarsky, K. Dmytriiuk, and M. Shketyn—automatically became delegates to the Central Rada.

On 27 November 1917 the Central Rada adopted the resolution proposed by the Kholm delegates that the Kholm region and Podlachia were an integral part of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) and placed all the evacuees and their institutions under the protection of the General Secretariat of the Central Rada, which was to establish political and administrative order in these regions. The Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed by the UNR and the Central Powers on 9 February 1918, recognized the Kholm region and Podlachia region, defined roughly by the borders of Kholm gubernia, as part of the UNR. This recognition provoked widespread Polish protest even in the Austrian Parliament. Ukrainian commissioners (Oleksander Skoropys-Yoltukhovsky, K. Dmytriiuk) were sent to establish order in the regions, and the evacuees slowly began returning home. There they met with concerted Polish opposition, tacitly supported by the Austrian authorities.

After the Central Powers capitulated, German troops were evacuated in December 1918, and in February 1919 Polish units occupied the Kholm region and Podlachia. Oleksander Skoropys-Yoltukhovsky and many Ukrainian teachers and leaders were imprisoned. Of the 389 Orthodox churches there in 1914, 149 were transferred to the Polish Catholic church; 111 were desecrated, looted, and closed down; and 79 were destroyed during the war or after by the Polish authorities.

1920–39. During the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 the Kholm region and Podlachia were briefly occupied by the Red Army in August. Polish rule of these regions was affirmed by the Polish-Soviet Peace Treaty of Riga. By 1922 many Ukrainian evacuees had returned to their devastated villages, even though the Polish authorities had made it difficult for them, particularly the Ukrainian intelligentsia, to do so. Because of Polish enmity, many remained in the USSR. Altogether, the number of Ukrainians in the region was about 120,000, or a third less than it had been in 1914.

In the interwar period no other Ukrainian territory under Polish rule was subjected to as much official Polonizing pressure as were the Kholm region and Podlachia within Lublin voivodeship. The schools were exclusively Polish, many of the prewar Ukrainian Orthodox churches were given to the Polish Catholic church, the land was distributed to the many Polish colonists who were brought in, and concerted efforts were made to convert the Orthodox to the newly fabricated ‘Roman Catholic church of the Eastern Rite.’ Yet the Ukrainians managed to set up their own community institutions, including the cultural-educational Ridna Khata society with 125 branches, co-operatives (which came under the Audit Union of Ukrainian Co-operatives in Lviv), the newspaper Nashe zhyttia (Kholm), and prayer houses to replace the churches that were not allowed to reopen by the authorities. They demonstrated their political unity in the 1922 Polish elections and, despite gerrymandering, managed to elect Pavlo Vasynchuk, Yosyp Skrypa, Semen Liubarsky, Stepan Makivka, Antin Vasynchuk, and Yakiv Voitiuk to the Sejm and Ivan Pasternak to the Senate. From 1926 the Polish regime became more authoritarian and repressive. It closed down the Ridna Khata society in 1930, prohibited Ukrainian theater and press, cut off the co-operative movement's links with Lviv, and instituted police surveillance and persecution of activists, many of them members of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine or the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance. Democratic Sejm elections were rendered impossible, and in 1928 only one Ukrainian was elected. Hundreds of citizens were imprisoned, many of them on trumped-up charges of being subversive communists. The only Ukrainian institution that was not outlawed was the Orthodox church, but even it was forced to use Polish as the official language of publication, religious instruction, and sermons. Its clergy was closely watched by the police, and many nationally conscious priests were relieved of their duties and not allowed to minister to their flocks. In late 1937 the Polish authorities began a mass demolition of Orthodox churches as ‘superflous entities’; by 1938, of 389 Orthodox churches in the Kholm region and Podlachia in 1914, 149 had become Roman Catholic churches and 189 had been wantonly destroyed by the Polish authorities (112 in 1938 alone). In the late 1930s the authorities tacitly condoned another means of repression against the Ukrainians: armed Polish gangs (‘krakusy’) that attacked Ukrainian homes and destroyed property.

1939–44. Two weeks after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, German troops had occupied all of the Kholm region and Podlachia, which became part of the Lublin district of the occupied Generalgouvernement of Poland. The Germans tolerated Ukrainian cultural activity, and in the larger Ukrainian communities various civic organizations sprang up within the first few weeks of the occupation. They organized refugee relief, defended the interests of the Ukrainian population before the authorities, established a network of Ukrainian schools, revived the branches of the Ridna Khata society and Ukrainian co-operatives, and took back many Orthodox churches that had been Romanized by the Poles. Local Ukrainians were assisted in this work by about 1,500 to 2,000 refugees from the Soviet-occupied Western Ukrainian territories and liberated political prisoners from Polish prisons and concentration camps, living in Lublin and other cities, where they worked as clerks in the German administration, agents of co-operatives, teachers, and community leaders. From 1940 a sizable number of refugee clergymen from Bukovyna performed pastoral functions in the region's Orthodox church. At the same time the German authorities resettled all indigenous Germans in western Poland and replaced them with Poles deported from there, thus increasing the local Polish population. In addition according to a German-Soviet repatriation agreement, about 5,000 indigenous Ukrainians were allowed to emigrate to Soviet Ukraine in 1940.

Soon after the occupation began, Ukrainian committees were created in Biłgoraj, Ternohorod, Tomaszów Lubelski, Zamość, Hrubeshiv, Kholm, Lublin, Volodava, Krasnystaw, and Biała Podlaska. A Central Kholm Committee was established in Kholm to oversee all Ukrainian activity, but in practice it limited itself to that of Kholm and Volodava counties. The most influential local leaders were Antin Pavliuk (chairman of the Central Kholm Committee), Semen Liubarsky, Volodymyr Kosonotsky, O. Rochniak, Volodymyr P. Ostrovsky in Zamość, Ivan Pasternak in Biała Podlaska, and Tymish Olesiiuk in Volodava. By November 1940 all the Ukrainian committees recognized the authority of an umbrella committee in Cracow headed by Volodymyr Kubijovyč which from June was called the Ukrainian Central Committee (UTsK), and the local committees became known as Ukrainian relief committees.

During the German occupation, the Ukrainian church underwent a revival. On 5 November 1939 a Provisional Orthodox Church Council already existed in Kholm, and soon a separate administration of the Orthodox church, led by Rev I. Levchuk and with Rev Mykola Maliuzhynsky as vicar general, was functioning. By the beginning of 1940 the number of Orthodox parishes had increased from 51 to 91. The restoration of the Kholm Cathedral to the Orthodox church on 19 May 1940 symbolized an end to Polish religious domination in the Kholm region. Representations by the Ukrainian Central Committee on behalf of the church before the German authorities led to the official sanctioning of the restored Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church and the restoration of Kholm eparchy (as the Kholm-Podlachia eparchy) and the consecration of Professor Ivan Ohiienko as archbishop of Kholm.

For the first time in the Kholm region and Podlachia, Ukrainian became the language of instruction in a network of elementary schools, the secondary technical and trade schools in Kholm, and the commercial schools in Volodava, Biała Podlaska, and Hrubeshiv. A Ukrainian gymnasium (with as many as 625 students) in Kholm and student residences in Kholm, Biała Podlaska, and Volodava were opened. Correspondence courses were organized by Ukrainian educational societies allowed by Germans. Local co-operatives were subordinated to county unions and an audit union in Lublin. Public Ukrainian activity was co-ordinated locally by the Ukrainian relief committees. A significant number of Ukrainians lived and worked in Lublin; there Volodymyr Tymtsiurak and, from 1941, L. Holeiko represented the Ukrainian Central Committee before the district governor. B. Hlibovytsky and Yevhen Pasternak in Biała Podlaska, Mykola Strutynsky in Hrubeshiv, and Roman Perfetsky in Zamość were noted local Ukrainian relief committee leaders. Thus Ukrainian national life flourished in the region as it never had before. Problems arose, however, with the Kalakuty, most of whom were indifferent to the Ukrainian organizational efforts.

After most of the Galician refugees returned to Galicia when it was occupied by the Germans in the summer of 1941, Ukrainian activity in the Kholm region and Podlachia began declining. In 1942 the anti-German Polish nationalist underground, later known as the Polish Home Army, also began a campaign of terror against the Ukrainians, burning down their villages and murdering the inhabitants. In Hrubeshiv county, the Ukrainians responded by organizing Samooborona (self-defense) units that had links with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. In 1943 the chairman of the Hrubeshiv relief committee, Mykola Strutynsky, the former senator Ivan Pasternak, the Samooborona commanders Ya. Halchevsky-Voinarovsky and Yu. Lukashchuk, and other Ukrainian leaders were assassinated by the Polish underground. In 1943 the Germans began forcibly deporting the inhabitants of many Polish and Ukrainian villages in Zamość and Tomaszów Lubelski counties with the aim of resettling Germans there and undermining the popular base of the undergrounds. This led to an upsurge in Polish underground activity and further German reprisals, which inflicted heavy losses on the Ukrainian peasants. In the summer of 1943 Soviet partisans also appeared in the Kholm region and Podlachia (see Soviet partisans in Ukraine, 1941–5). In 1944, as the Soviet Army advanced into the regions, Polish communist partisans became active there.

1944 to the present. In July 1944 the entire Kholm region and Podlachia were occupied by the Soviet Army, and Kholm became the provisional capital of the Communist Polish People's Republic. In September 1944 a temporary Soviet-Polish border, following roughly the former Curzon Line along the Buh River, was agreed upon. The border was settled in August 1945, and the Kholm region and Podlachia remained part of Poland as the eastern part of Lublin voivodeship.

On 3 September 1944 the Polish-Soviet authorities had signed an agreement in Lublin on the voluntary resettlement of Ukrainians living in Poland to Ukraine and of Poles living in Soviet Ukraine to Poland. The population transfer began in October 1944. By August 1946, 193,500 Ukrainians from the Kholm region and Podlachia had been resettled in Ukraine. Both the Polish Home Army and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army opposed the postwar regime and tried to sabotage the resettlement operation; in 1945 they even co-operated by restricting their operations to mutually agreed spheres of interest. Soviet and Polish government forces ensured the success of the resettlement operation, however, and only a small Ukrainian population—25,000 to 40,000—remained when it ended, in the southeastern part of Hrubeshiv county and in a thin strip along the Buh River in Biała Podlaska and Volodava counties.

In 1947 almost all of the remaining Ukrainians were forcibly resettled in the western and northern territories annexed by Poland after the war (see Operation Wisła). Between 1953 and 1966 about 12,000 managed to return to their ancestral lands. They were concentrated in a strip along the Buh River, mostly in Podlachia. Although they belonged to the Polish Autocephalous Orthodox church, they lacked many of the limited rights that were enjoyed by Ukrainians in other parts of postwar Poland; the Ukrainian language was not taught in any school, branches of the Ukrainian Social and Cultural Society could not be organized there, and persecution and discrimination had caused most Ukrainians to hide their ethnic identity and even to assimilate. The Ukrainian population in northern Podlachia was somewhat better off; most of it was not resettled, but it is officially considered to be Belarusian and was served by Belarusian schools and associations.

Population. In the second half of the 16th century, the Kholm land had 20 towns and 401 villages with a population of approximately 67,000. In 1867 the Ukrainian population was 217,300, of whom only 2,000 were Orthodox. In 1900 the population consisted of 463,902 Ukrainians and Belarusians (51.8 percent), 268,053 Poles (29.9 percent), 135,239 Jews (15.1 percent), and 29,123 others (3.2 percent). In 1939 the total population was 720,000, comprising 220,000 Ukrainians and 160,000 Kalakuty (together 52.8 percent), 260,000 Poles, 70,000 Jews, and 13,000 Germans. The most densely populated areas were the fertile chornozem parts of Hrubeshiv and Tomaszów Lubelski counties, while the least populated was the sandy-soil area of Biłgoraj county. In 1931 only 18 percent of the population was urban; the largest towns were Kholm (1931 pop 38,600), Zamość (24,700), Hrubeshiv (12,600), Tomaszów Lubelski (9,600), and outside Ukrainian ethnic territory, Krasnystaw (14,600) and Biłgoraj (13,800).

As a result of assimilation, the proportion of Ukrainian population in the Kholm region dropped over the years, though not as much as it did in Podlachia. Table 1 and Table 2 show this decline in terms of religious affiliation. It must be pointed out, however, that many of those who were classified as Roman Catholics were of Ukrainian origin. The Kholm region was a mixed Ukrainian-Polish ethnic territory. The Ukrainians were in a majority only in a narrow strip along the Buh River, particularly in Hrubeshiv county, but they were in a minority in every other county.

In 1931 the unreliable Polish census listed a population of 2,464,900 in Lublin voivodeship, of which Ukrainians made up 8.6 percent (212,000). Jews made up 12.8 percent (315,500), of whom about 70,000 lived in the Kholm region. Most of them lived in urban centers (up to the 20th century two-thirds of the region's urban population was Jewish). Most of them perished in the Nazi Holocaust. In 1931 there were only 13,000 Germans in Kholm county and the adjacent part of Volodava county. In 1914 there had been 31,500, most of whom had arrived after 1883 and settled on land as agricultural colonists. In 1915 all the Germans were deported by the Russian army, mostly to Siberia; only some of them were repatriated in 1920. In fall 1939 the German occupation authorities resettled them in the Third Reich. Thus, after the forced resettlement of Ukrainians in 1947, the Kholm region became an essentially Polish ethnic territory.

Economy. Throughout its history the Kholm region has been an agricultural land. Until 1939 about 80 percent of the population, including virtually all the Ukrainians, depended on subsistence farming for their livelihood. Large forests remained only in Biłgoraj county and the Roztochia Hills in the south. Arable land constituted 70 percent of the region's area; 51 percent of it was cultivated, 1.5 percent was orchards and gardens, 18 percent was meadows and hayfields, 24 percent was still forested, and 5.5 percent was wasteland. The principal crops grown were rye (30 percent of the seeded area), wheat (18 percent), potatoes (16 percent), oats (15 percent), fodder crops (11 percent), barley (8 percent), and industrial crops (mostly sugar beets, 2 percent). Dairy farming and hog raising were the only agricultural branches that generated large surpluses.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bańkowski, E. Ruś Chełmska od czasu rozbioru Polski (Lviv 1887)

Petrov, N. Kholmskaia Rus’ (Saint Petersburg 1887)

Kolberg, O. Chełmskie: Obraz etnograficzny, 2 vols (Cracow 1890–1; repr: Wrocław–Poznań 1964)

Ploshchanskii, V. Proshloe Kholmskoi Rusi (Vilnius 1899)

Frantsev, V. Karty russkogo i pravoslavnogo naseleniia Kholmskoi Rusi (Warsaw 1909)

Dymcha, L. de. La question de Chelm (Paris 1911)

Wierciński, H. Jeszcze z powodu wydzielenia Chełmszczyzny (Cracow 1913)

—Ziemia Chełmska i Podlasie (Warsaw 1916)

Korduba, M. Istoriia Kholmshchyny i Pidliashshia (Cracow 1941)

Pasternak, Ie. Narys istoriï Kholmshchyny i Pidliashshia (novishi chasy) (Winnipeg–Toronto 1968)

Kubiiovych, V. Ukraïntsi v Heneral’nii Huberniï, 1939–1941 (Chicago 1975)

Nahaievs’kyi, I. ‘Prychynky do istoriï Kholms’koï zemli,’ Bohosloviia, 39 (1975)

Borysenko, Valentyna et al (eds). Kholmshchyna i Pidliashshia: Istoryko-etnohrafichne doslidzhennia (Kyiv 1997)

Hornyi, Mykhailo. Ukraïntsi Kholmshchyny i Pidliashshia: Vydatni osoby XX stolittia (Lviv 1997)

Isaievych, Iaroslav et al (eds.) Volyn' i Kholmshchyna 1938–1947: Pol's'ko ukraïns'ke protystoiannia ta ioho vidlunnia (Lviv 2003)

Makar, Iurii. Kholmshchyna i Pidliashshia v pershii polovyni XX stolittia (Lviv 2003)

Wysocki, Jacek. Ukraińcy na Lubelszczyznie w latach 1944–1989 (Lublin 2011)

Havryliuk, Iurii. De tserkvy stoiat' i mova lunaie (Lviv 2012)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč

[This article was updated in 2013.]

Cathedral of the Mother of God.jpg)

Orthodox cemetary.jpg)

Orthodox Church.jpg)

Orthodox Church of the Nativity of Mother of God.jpg)

Orthodox Church of the Nativity of Mother of God (interior).jpg)

(panorama).jpg)