Kholm

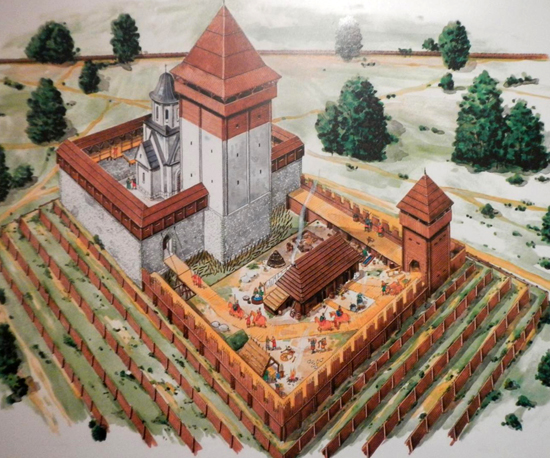

Kholm [Холм; Xolm] (Polish: Chełm). Map: II-4. The principal city (2019 pop 60,217) of the Kholm region, situated on the steep bank of the Uherka River, a tributary of the Buh River; from 1975 to 1999 the capital of Chełm voivodeship in Poland, currently a city in Lublin voivodeship. The date of its origin is unknown. In 1237 Prince Danylo Romanovych of Volhynia built a castle there and reinforced the town with stone walls and with defensive towers in the neighboring villages of Bilavyne and Stovp. As a result Kholm withstood the Mongol invasion of 1240. At that time the trade route linking Kyivan Rus’ via Galicia with the Mediterranean lost its importance because of Constantinople's decline and the Mongols' control of the steppes and was supplanted by the route linking western Rus’ via the Buh River and the Vistula River with the Baltic Sea ports and the realm of the Teutonic Knights. Because Kholm was located on the latter route, after also becoming the ruler of Galicia, Danylo made it his capital and the see of Kholm eparchy. Starting in the 1250s he constructed a formidable fortress in Kholm and transformed the city into an important commercial and cultural center.

As the capital of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia (until 1272) and then of an appanage Kholm principality, the town withstood another Mongol siege (1261) but suffered greatly during the Lithuanian-Polish-Hungarian wars for control of Galicia-Volhynia in the 14th century before being annexed by Poland in 1387. In 1392 the city obtained the rights of Magdeburg law, which were later supplemented with royal privileges. From 1484 it and the Kholm region were part of Rus’ voivodeship. From the mid-15th century Kholm was an important trade center. Yet in 1612 it had only 2,200 inhabitants, 800 of whom were Jews. As an eparchial see and religious-educational center, it had some cultural influence. From the mid-17th century Kholm declined because of Poland's continual wars. In 1648, during the Cossack-Polish War, it was captured and briefly held by the Cossack army of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Later it was ravaged by Swedish and Muscovite troops, particularly during the Great Northern War (1700–21). In the late 18th century its population was only 2,500 (over 1,000 Jews, 1,000 Poles, and only 200 Uniate Ukrainians).

After the Third Partition of Poland the town belonged to Austria (1795–1807), the Grand Duchy of Warsaw (1807–12), the Congress Kingdom of Poland (1812–32), and Russia (1832–1917). It remained a small Polonized county capital and trade center with a predominantly Jewish population (in 1860, 2,480 of its 3,600 inhabitants were Jews). Its importance was as the see of a Uniate Kholm eparchy. In the second half of the 19th century, Russians, mostly civil servants, began settling in Kholm. In 1873 it had a population of 5,595, consisting of 263 Orthodox (Russians), 530 Uniates (Ukrainians), 1,294 Roman Catholics (Poles), and 1,503 Jews. By 1911 its population had grown to 21,425, consisting of 5,181 Orthodox (Ukrainians and Russians), 3,820 Roman Catholics (Poles), 12,100 Jews, and 315 Lutherans (Germans). With the abolition of the Uniate church and the influx of Russian Orthodox clergy, Russian influence grew, and Kholm became the center of Russification in the Kholm region, with several Russian secondary schools and a theological seminary. During the brief liberal period after the Revolution of 1905 the city's Ukrainian inhabitants were able to establish the Prosvita Enlightenment Society of Kholm Rus’ (which published the bilingual Ukrainian-Russian journal Brats’ka besida) and a Prosvita society, but after Kholm gubernia was formed in 1912, Russification pressures increased with the rise in the number of Russian functionaries in the city.

During the First World War almost all of Kholm's Ukrainians and Russians were evacuated east in 1915, before its capture by the Austrian army. Many Ukrainians returned in 1920–2, those who had been in the Ukrainian National Republic with a developed national identity. Under interwar Polish rule (1921–39) the city was a minor center of Ukrainian life. The region's cultural-educational Ridna Khata society was centered there. Published there were the pro-Soviet and Socialist weeklies Nashe zhyttia (Kholm) (1921–8), Selians’kyi shliakh (1927–8), and Nove zhyttia (Kholm) (1928–30), calendars, and other materials. In the late 1920s, however, these activities and publications were suppressed by the Polish authorities, as was Ukrainian church life (the city's Orthodox cathedral and cemetery were desecrated by the Poles and closed down as early as 1919).

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Kholm was part of the Generalgouvernement and experienced a resurgence of Ukrainian activity to which refugees from Soviet-occupied Galicia made an important contribution. A Ukrainian Committee and Provisional Church Council were formed. Thanks to the efforts of the Ukrainian Central Committee in Cracow the Orthodox cathedral was restored to the Ukrainians, and Kholm became the see of the new Kholm-Podlachia eparchy; its archbishop, Ivan Ohiienko, established a small seminary there. A Ukrainian Relief Committee was also active there. Ukrainian schools (including a gymnasium, a technical school, and two trade schools), educational and artistic groups, a theater troupe, co-operatives, and various private businesses were allowed to function. This revival was cut short by the Soviet and Polish Communist occupation in July 1944. Many of Kholm's active Ukrainians fled west to Germany and emigrated after the Second World War to the New World. The majority of those who stayed behind were forcibly resettled in 1946 by the Polish authorities in the former German territories of western Poland. Today only a small number of Ukrainians live in Kholm, where they have an Orthodox parish.

The city's most important architectural monument is the Cathedral of the Mother of God built by Prince Danylo Romanovych in the mid-13th century on Castle Hill. Rebuilt after being destroyed by fire in 1256, at the end of the 16th century (1736–57) it became the residence of the Uniate bishop. It underwent major alterations in 1638–40 under Bishop Metodii Terletsky and was renovated in 1735–56 in the style of the late baroque. Minor alterations were made in 1874–8 after it became an Orthodox church. Its iconostasis, many icons, and several murals were destroyed by the Poles in 1919, after which it belonged to the Roman Catholic church. Further changes were made after the building was restored to the Orthodox church in 1940, and again after it was taken over once more by the Roman Catholic church in 1946. The miraculous medieval icon of the Theotokos has been preserved in the cathedral. Other architectural monuments in the city include the Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit (1849), a Roman Catholic church in the late rococo style (1753–63) designed by P. Fontana, and the monastery of the Franciscan Reformaci (1736–40, rebuilt in the 19th century). The city's museum contains many masterpieces of church art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Batiushkov, P. Kholmskaia Rus’ (Saint Petersburg 1887)

Czernicki, K. Chełm, przeszłość i pamiątki (Kholm 1936)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Misto Kholm (Cracow 1941); repr in Nadbuzhanshchyna: Istorychno-memuarnyi zbirnyk, 1, ed M. Martyniuk et al (New York–Paris–Sydney–Toronto 1986)

Pasternak, Ie. Narys istoriï Kholmshchyny i Pidliashshia (Novishi chasy) (Winnipeg–Toronto 1968)

Zimmer, B. Miasto Chełm: Zarys historyczny (Warsaw–Cracow 1974)

Havryliuk, Iurii. De tserkvy stoiat' i mova lunaie (Lviv 2012)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč

[This article was updated in 2013.]

city center.jpg)

Cathedral of the Mother of God.jpg)

John the Theologian Orthodox Church.jpg)

Orthodox cemetary.jpg)

aerial view.jpg)