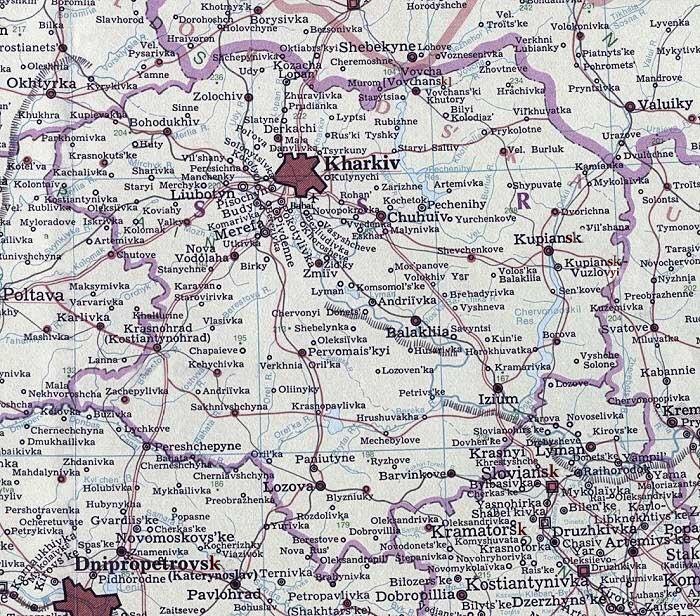

Kharkiv oblast

Kharkiv oblast [Харківська область; Kharkivska oblast]. (Map: Kharkiv oblast.) An administrative region in northeastern Ukraine formed on 27 February 1932, with an area of 31,400 sq km and a population in 2005 of 2,848,000. The oblast has 27 raions, 17 cities, 61 towns (smt), 381 rural councils and 1,683 villages and smaller rural settlements. The oblast’s capital is Kharkiv.

Physical geography. The oblast’s western half is in the Dnipro Lowland, the southeastern third of the oblast is in the Donets Lowland, and its northern part is in the Central Upland. The vegetation in is of the steppe and forest-steppe variety. The oblast's northwestern forest-steppe has medium-humus chornozem, dark-gray podzolized, and podzolized chornozem soils. Its eastern and southern steppe has ordinary medium-humus chornozems and, in the river valleys, soddy, weakly podzolized meadow-chornozem and also marshy soils. Forests cover 9.4 percent of the oblast. Large deposits of natural gas (30 percent of Ukraine’s proven reserves), petroleum and gas condensate (8 percent of Ukraine’s proven reserves), and significant deposits of peat, anthracite, lignite, rock salt, iron ores, phosphates, limestone, marls, ordinary and quartzose sands, chalk, refractory clays, zinc, and ocher are located there.

The largest waterways in the oblast are the Donets River and its right-bank tributaries the Udy River (aka Uda, with its tributaries the Kharkiv River and the Lopan River), the Mozh River, the Chepil River, and the Bereka River (with its tributary the Brytai River); the Donets’s left-bank tributaries the Vovcha River, the Velykyi Burluk River, the Voloska Balakliika River, and the Oskil River; and the Merlia River (aka Merlo) and the Orel River (aka Oril) with its tributaries the Orilka, the Berestova, and the Bahata rivers of the Dnipro River Basin. This network is supplemented by the Dnipro-Donbas Canal, which draws water from the Dnipro and follows the Orel, Orilka, lower Brytai, and Bereka rivers to the Donets River. The needs for municipal and industrial water supply also led to the creation of the Pechenihy Reservoir on the Donets River, the Chervonooskil Reservoir on the Oskil River, the Krasnopavlivka Reservoir and the Orilka Reservoir along the Dnipro-Donbas Canal. Mineral springs and several small natural lakes are found in the oblast; most of the natural lakes are in the Donets marshlands (Lyman, Borove, Bile, Lebiazhe, Chaika).

The oblast’s climate is temperate-continental, with an average temperature in January of -7 to -8̊C and in July of 19.5 to 21.5̊C. The annual precipitation ranges from 490 mm in the southeast to 570 mm in the northwest. Dry spells occur in the summer, and dry winds and dust storms in the spring.

History. In the Middle Ages, the oblast's territories belonged to the Kyiv principality and Chernihiv principality of Kyivan Rus’. With the Mongol invasions of the 13th century they were largely depopulated and constituted part of what became known as “Dyke Pole” (Loca Deserta). In the 16th century the lands became nominally part of Muscovy. Ukrainian Cossacks and Ukrainian and Russian peasants began settling there, and in the 17th and 18th centuries the oblast’s lands constituted parts of the Cossack Kharkiv regiment and Izium regiment of Slobidska Ukraine. From 1765 they were under direct tsarist rule as part of Slobidska Ukraine gubernia (1765-80, 1796-1835), Kharkiv vicegerency (1780-96), and Kharkiv gubernia (1835-1917). During the Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917-21, the gubernia changed hands several times among the Ukrainian National Republic, the Hetman government, the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic, the Red Army, and the Russian Volunteer Army. Soviet rule over the gubernia was consolidated in 1920. In 1925 the gubernia was abolished, and its territory was divided among Kharkiv, Izium, Kupianka (now Kupiansk), and Sumy okruhas. In 1932 the okruhas were amalgamated to create Kharkiv oblast. Its borders were modified several times; in 1937 parts of the oblast were incorporated into the newly created Poltava oblast, and in 1939, Sumy oblast.

Population. The oblast's population did not grow between 1930 and 1945 because of the many deaths and deportations that occurred during the Stalinist Terror, the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3, and the Second World War. In 1959 it was 2,520,000, less than the 2,556,000 counted in 1939. By 1965 it had increased to 2,650,000, reaching a peak of 3,196,600 in 1990. Since then, as a result of sharply decreasing birth rates and growing death rates, the population has again declined, to 2,848,000 in 2005.

In 1965, the average density was 75 inhabitants per sq km; by 1990 it had risen to 102, but by 2005 it had receded to 91 inhabitants per sq km. The proportion of urban dwellers grew from about 25 percent in the mid-1920s to 53 percent in 1939, 69 percent in 1970, and 79 percent in 2005. Ukrainians made up a declining share of the oblast’s population: 68.8 percent in 1959, 66.1 percent in 1970, 64.2 percent in 1979, and 62.8 percent in 1989. But with Ukraine’s independence in December 2001, 70.7 percent of the oblast’s population declared itself Ukrainian. This shift is more than the post-independence repatriation movement would explain, and may be reflective of the children of mixed parentage preferring to identify themselves now as Ukrainians.

During the Soviet period the share of ethnic Russians and Belarusians in the oblast’s population increased, while that of the Jews declined. Their respective percentages for 1959, 1970, 1979, and 1989 were: Russians, 26.4, 29.3, 31.8, and 33.2 percent; Belarusians, 0.47, 0.62, 0.65 and 0.72 percent; and Jews, 3.3, 2.7, 2.1, and 1.5 percent. In post-Soviet Ukraine the shares of all three minorities declined: in 2001 Russians made up 25.6 percent of the oblast’s population; Belarusians, 0.51 percent; and Jews, 0.40 percent.

However, linguistic Russification is well advanced: whereas in 1959, 89.0 percent of the oblast's Ukrainians claimed the Ukrainian language as their first language, by 1989 only 79.5 percent did so. In independent Ukraine the percentage of Ukrainians in the oblast claiming Ukrainian as their first language has continued to decline, to 74.1 percent of all the oblast’s Ukrainian inhabitants and 66.8 percent of its urban Ukrainians in 2001. Meanwhile, 95.6 percent of the oblast’s Russians, 93.5 percent of its Jews, and 60.1 percent of its Belarusians claimed Russian as their first language. This suggests that the process of linguistic Russification has not been reversed in independent Ukraine. Indeed, the Russian language has become a political wedge issue. In elections for the president of Ukraine, many inhabitants of the oblast have voted for the candidate who has articulated support for the introduction of Russian as Ukraine’s second official language. In April 2006, contrary to Ukraine’s constitution, which stipulates Ukrainian as the only official language, the Kharkiv oblast council voted in favor of granting Russian an official status in the oblast.

In 2005 the most populous cities in the oblast were Kharkiv (1,465,000 or 51.4 percent of the oblast’s population), Lozova (61,400), Izium (54,600), Chuhuiv (34,400), Kupiansk (31,200), Balakliia (30,900), and Liubotyn (22,500).

Industry. The oblast is one of the most industrialized in Ukraine. In 2000, with 5.9 percent of Ukraine’s population, the oblast produced 6.8 percent of the value of the country’s industrial output, including 12.3 percent of Ukraine’s machines, 8.9 percent of its processed food, 6.5 percent of its fuel and energy, and 3.9 percent of its light industry output. Since the demise of the USSR in 1991, the oblast’s industrial output has declined, resulting in significant unemployment (15.2 percent in the cities in 2000).

In response to new market conditions, the industrial mix has also changed. Between 1990 and 2000, the share of machine building and the metalworking industry in the oblast’s total value of industrial output declined from 54.1 percent to 29.0 percent; of light industry (clothing, textiles, footwear), from 11.2 percent to 1.0 percent; of the chemical and petrochemical industries, from 2.7 to 1.2 percent; and of the building-materials industry, from 3.1 to 2.7 percent. Meanwhile the value of output of the oblast’s food industry increased from 18.7 to 28.8 percent; of electric power, from 3.4 to 15.5 percent; of the fuel industry, from 1.0 to 12.9 percent, of the medical technology industry, from 2.0 to 3.5 percent; and of the lumber industry, woodworking industry, and paper industry, from 1.1 to 2.2 percent. Other branches experienced smaller shifts: the metallurgical industry, from 1.3 to 1.4 percent, and other industries, from 1.4 to 1.8 percent.

Machine building, metallurgy, and the metallurgical industry in the oblast are concentrated in Kharkiv (turbines for electric-power generating stations, electric motors, diesel engines, tractors, power tools and equipment, aircraft assembly, electronics and avionics). Secondary plants are found in the nearby cities of Chuhuiv, Derhachi, and Izium, in the more distant Kupiansk to the east, and in Lozova and adjacent Paniutyne to the south. Kharkiv is Ukraine’s primary producer of confectioneries. The oblast’s largest sugar refineries are in Kupiansk and Orilka; smaller ones are located in the towns of Huty, Bilyi Kolodiaz, Kostiantynivka, Chapaieve, and Savyntsi. Flour mills are found in Kharkiv, Krasnohrad, Vovchansk, and Barvinkove. The oblast’s major bakeries are in Kharkiv, Vovchansk, Kupiansk, Lozova, and Krasnohrad. The vegetable-oil industry is concentrated in Kharkiv, Vovchansk, and the town of Prykolotne; the meat-processing industry, in Kharkiv, Lozova, Izium, Kupiansk, Krasnohrad, Chuhuiv, and Vovchansk; the dairy industry, in Kharkiv, Barvinkove, Bohodukhiv, Izium, and Kupiansk; Enterprises of liquor and spirits distilling, the brewing industry, and the wine-making industry are mostly in Kharkiv; distilleries are also located in Merefa and Liubotyn. Plants of the tobacco industry are located in Kharkiv and Krasnohrad.

The oblast’s light industry (textiles, clothing, footwear, and leather goods) is concentrated in Kharkiv. Cotton mills are also found in Krasnohrad, Liubotyn, Vovchansk, and the village of Komarivka. Sewing plants are also located in Valky, Bohodukhiv, Derhachi, the town of Pechenihy, Kupiansk, Lozova, and the village of Hrushuvakha in Barvinkove raion. Footwear is also made in Vovchansk. Various building materials are made in Kharkiv; porcelain and ceramic tiles, in the town of Budy; asbestos, cement, reinforced-concrete, and slate products, in Balakliia; and glass, in Merefa. Wood products and furniture are made in Kharkiv, Merefa, the town of Vilshany, Derhachi, Chuhuiv and Izium. Pulp and paper mills are located in Zmiiv and the town of Rohan. The oblast’s printing industry is concentrated in Kharkiv.

Chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics are made in Kharkiv and the town of Pervomaiskyi. Medical equipment is produced in Kharkiv and Izium. Natural gas extracted from the deposits at the Shebelynka gas field, the town of Kehychivka, the villages of Yefremivka in Pervomaiskyi raion, Melykhivka in Nova Vodolaha raion, Khrestyshche, Sosnivka, and Berezivka in Krasnohrad raion, and elsewhere is the oblast's main source of fuel. Electricity is generated by two large regional thermal power stations at Zmiiv and the town of Eskhar, and by smaller thermal co-generating stations in Kharkiv, Kupiansk, and Vovchansk.

Agriculture. Kharkiv oblast is a major agricultural producer in Ukraine. Occupying 5.2 percent of the country’s area, it has 6.2 percent of Ukraine’s arable land. In 2003 the oblast produced 5.6 percent of the value of Ukraine’s total agricultural output. Grains, vegetables, fruit, fodder crops, industrial crops, livestock, and poultry produced on many small and some large farms provide raw material for the oblast’s vibrant food industry.

In 1983 there were 274 collective and 158 state farms in the oblast. Associated with these large enterprises were over 220,000 private plots worked by the residents of those farms. With the introduction of agrarian reforms in independent Ukraine, many of the collective and state farms were broken up into autonomous, smaller enterprises, and individuals were allowed to leave the collective farms and establish their own family farms. By 1998 there were 718 large farms (444 collective enterprises, 204 state enterprises, 25 co-operatives, 45 joint-stock companies) and 1,160 family farms in the oblast. In addition, villagers working on the large farms and urban dwellers seeking to grow their own vegetables cultivated 582,000 private plots. By 2003 the number of large farms had increased to 831 (411 farming associations, 242 private enterprises, 50 farm cooperatives, 40 state enterprises and 88 other forms of farm-holding), and there were 1,332 family farms. The number of private plots probably remained about the same.

Land used for farming in the oblast has declined slightly since 1990, reflecting the rising costs of inputs, a decline in livestock and a corresponding decline in the demand for feed. In 1988 of all the land held by farming enterprises (2,671,000 ha), 90.4 percent (2,414,000 ha) was classified as farmland. Of the latter, 82.4 percent (1,989,000 ha) was used for crops and 15.8 percent (382,000 ha) as pasture and hayfields. By 1998 the land held by all farming enterprises declined to 2,616,000 ha, of which 91.4 percent (2,390,000 ha) was classified as farmland; of the latter, 81.6 percent (1,950,000 ha) was used for crops, but 16.4 percent (391,000 ha) for pastures and hayfields. Sown area declined from 1,839,000 ha in 1988 to 1,639,000 ha in 1998 and 1,548,000 ha in 2003. Its crop composition also changed from 1988 to 2003: grains (winter wheat, spring barley, corn, millet, and buckwheat) declined from 50.3 to 45.9 percent, and feed crops (corn for silage, root crops and sugar beets for feed, sown annual and perennial grasses for hay) declined sharply from 30.9 to 19.1 percent. But the production of industrial crops (sugar beets, sunflowers) increased from 13.9 to 27.1 percent; and of potatoes, vegetables, and melons, from 4.8 to 7.9 percent.

In 1997 animal husbandry accounted for 32.6 percent of the oblast’s agricultural output. In 2003 the oblast had 4.7 percent of the cattle (366,000 head), 4.0 percent of the cows (171,700 head), 4.2 percent of the pigs (306,500 head) and 3.9 percent of the sheep and goats (71,600 head) in Ukraine; and it produced 6.1 percent of the country’s meat, 4.6 percent of the milk, and 5.5 percent of the eggs. Cattle raising prevails in the oblast, but hogs, poultry, sheep, goats, rabbits, honey bees, and fish are also produced.

Transportation. In 1989 the oblast had 1,523 km of railway, of which 1,016 km was electric. Trunk lines crossing the oblast include the Moscow–Kharkiv–Sevastopol, Briansk–Kharkiv–Mariupol, Moscow–Kharkiv–Donetsk, and Lviv–Kyiv–Poltava–Kharkiv–Kupiansk–Valuiky lines. The major junctions are Kharkiv, Kupiansk, Krasnohrad, Merefa, and Liubotyn. In 1989 there were 8,700 km of roads in the oblast, 8,000 of which were paved. The density of paved roads per 1,000 sq km is 253.4 km. In 2003 truck transportation in the oblast moved 33.3 million tonnes, or 3.4 percent of Ukraine’s freight. The truck freight turnover was 1,230 million km, or 5.0 percent of Ukraine’s total. The major highways are Moscow–Kharkiv–Simferopol and Kyiv–Kharkiv–Rostov-na-Donu. An international airport is located near Kharkiv. Crossing the oblast are major gas pipelines. One set radiates in three directions from Shebelynka: north to Kharkiv and thence to Russia; west to Poltava and thence to Kyiv or to Kremenchuk; and south to Lozova and thence southwest to Dnipro, Kryvyi Rih, Mykolaiv, and Odesa. Another represents the major Soiuz transit pipeline that carries gas from Orenburg in Russia westward through Shebelynka to central Europe. A feeder pipeline bringing more gas from Russia via Ostrogozhsk passes Kupiansk and Chuhuiv to Shebelynka. Porous rock formations at Shebelynka (with its now depleting gas deposits) serve as active storage for natural gas from Russia.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Istoriia mist i sil Ukraїns’koї RSR: Kharkivs’ka oblast’, ed. M. A. Siroshtan et al (Kyiv 1967; Russian edn 1976)

Sotsial’no-ekonomichna heohrafiia Ukraїny (Lviv 2000)

Cherniuk, L.; Klynovyi, D. Ekonomika rehioniv (oblastei) Ukraїny (Kyiv 2002)

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2006.]

.jpg)

.jpg)