Kerch

Kerch [Керч; Kerč]. See Google Map, see EU map: VIII-17. City (2021 pop 154,621) and port on the Kerch Strait in the eastern Crimea. Divided into three city raions from 1938 until 1988, it is a significant historic, industrial and transportation center.

History. Kerch is one of the oldest cities in Ukraine. Throughout its existence it had different names: Panticapaeum (6th century BC), Bospor (6th century AD), Karcha (7th century), Korchev (9th century), Vosporo, Cherkio (13th century), Cherzeti (15th century), and since the 18th century, Kerch. The land was inhabited by humans since the Paleolithic Period, with rich finds from the Mesolithic Period and Neolithic Period.

The city was established as Panticapaeum at the end of 7th century BC by Greek seafarers from Miletus (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast). Located on a fish migration channel (the name of the city, in one of the local dialects, is thought to have meant the way of the fish) and shipping trade routes (north-south and east-west), it developed into an important fishing and trade center. Legend has it that its Cimmerian predecessor was founded by the son of King Aeëtes of Colchis, who possessed the Golden Fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts. According to Herodotus and Strabo, Greek settlers called the strait the Cimmerian Bosporus between Pontus Euxinus (the Black Sea) and the fish-rich Meotida (or Meotis Palus, the Sea of Azov) and recalled its preceding city, Cimmericon (evidenced by its remains of the Golden Mound), in the land of Cimmeria. In the succeeding century, Panticapaeum became the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom (a Greco-Scythian state that had smaller cities on both sides of the strait). Its chief export to Athens was grain, but its industry included the processing of fish, animal products, wine, ceramics, textiles, jewelry and metallurgy.

From the middle of the 1st century BC it was a Roman dependency with its own Hellenized Sarmatian dynasty. Its state emblem was a Poseidon trident with a dolphin. Apostle Saint Andrew the First Called is said to have come to the Crimea by way of Panticapaeum and preached there first. By the 2nd century AD the city already had a community of Christians, who had carved straight crosses on an ancient well. The city and the Kingdom of Bosporus suffered severely from the Ostrogoth raids; then the city was devastated by the Huns in AD 375.

In the 6th century it revived under Byzantine protection, when the citadel Bospor was built and its seat of Christian eparchy established there. In 576 the city was sacked by the Khazars and then taken and re-named (7th century) Karcha from Turkic ‘kierech’ meaning ‘limestone.’ In the 8th-9th centuries the Rus’ drove out the Khazars, adapted the city name to Korchev and included it in their newly-established principality (across the Kerch Strait) at Tmutorokan (the name derived from the Khazar fortress they took, Tamantarkhan).

From the 10th to the 12th century Korchev (in modern Ukrainian, Korchiv), now led by Slavic merchants, belonged to the Tmutorokan principality and was a center of trade between Kyivan Rus’ and the Crimea, Caucasia, and the Orient. In the 12th century it was called both Korchev and Bospor as it became a protectorate of Byzantium and in 1204 its rump successor, the Trebizond (Trapesund) Empire. Interaction with Kyivan Rus’ was cut off by the Pechenegs and Cumans and then the Mongol invasion and the Golden Horde.

When the Venetian merchants arrived in the city, seeking trade with the Orient by way of the Golden Horde, they re-named it Vosporo or Cerco (Cherkio), but in 1318 they were replaced by the more aggressive Genoese, who improved its port with a breakwater and strengthened its fortifications.

In 1475 the fortified city on the geostrategic crossroads fell to the Turks, who re-named it Cherzeti. It served as a slave market and was raided by Zaporozhian Cossacks (1556, 1559, 1560, 1623, 1624, 1631, 1634, 1659, 1662) to free the slaves. After the Turks lost Azak (Azov [Russian] or Oziv [Ukrainian]) at the mouth of the Don River to Muscovy (1696), they built the citadel Yenikale (in 1706) 10 km east of Cherzeti to control the northern entry to the Kerch Strait. Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74, by the Peace Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), Kerch (as the Russians and Ukrainians called it) and its neighboring fortress of Yenikale were ceded to the Russian Empire.

In the Russian Empire. After the 1770s, Kerch, together with Yenikale and a small buffer of rural settlements, formed the Kerch-Yenikale City Administration, answering directly to the Ministry of the Interior of the Russian Empire. The Kerch-Yenikale City Administration territory of 163.77 sq km was retained until 1920. The Russian authorities initially resettled the abandoned city with 1,236 military and civilian personnel, followed by ethnic Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Armenian and Italian settlers. By 1775 Kerch (with Yenikale) became the first naval base of the Russian Empire on the Black Sea until 1784, when this role was overshadowed by Sevastopol. As an exclave (1775–83), it was part of the Azov province of the New Russia gubernia; after Russia’s annexation of the Crimea (1784), it was in the Teodosiia county of Tavriia oblast and then (1802) of Tavriia guberniia.

Because of its location, from 1821 Kerch resumed its role as a trade and fishing port. That year it obtained official Kerch-Yenikale city status, the requirement to quarantine incoming ships, a customs office in 1824, and relief from taxes for 25 years in 1825. The traditional industries of fishing, salt preparing and quarrying of limestone were augmented with metallurgy. Iron ore, the surface deposit re-discovered in 1783 (see Kerch Iron-ore Basin), was tested (1825) and then brought into production (1846) of pig iron at two small furnaces in Kerch. Tobacco curing, canning, and brick-making were added. The city administrator, Ivan Stempkovsky (1826–32, of ethnic Polish origin), himself an avid archeologist, planned the city (architects F. Shal, O. Digby) so as to connect symbolically the ancient with the modern. One of the first museums of antiquity in the Russian Empire was opened in Kerch in 1826. Development of this city plan was completed under the city administrator Colonel Prince Zakhar Kherkeulidze (1833–50). Education was also promoted with the establishment of a school of foreign trade (1828) and the G. Kushnikov Institute for Daughters of the Nobility (first in the Crimea, 1835). A chapel honoring Stempkovsky in the classicist mini-temple form was built on top of Mount Mitridat with a panoramic view of the city.

During the Crimean War in 1855 the British looted the city, burned the docks and destroyed three quarters of the buildings and the iron smelter. To prevent a similar disaster, the Kerch Fortress (originally built by the Turks in 1771) at the Ak-Burun Point, was completely re-built in 1857–77 to shelter the city from the south (Black Sea) side. By the 1860s the city not only recovered (buildings, tobacco factories); it developed with the coming of the British (Bombay-London) telegraph facility (1870s), the extraction of crude oil at Komysh-Buruny (by a French firm, 1880s), the construction of a large metallurgical plant (1897–1900), and the railway link via Dzhankoi to the Donets Basin and the rest of the Russian Empire (1900). Industrial workers in the city held strikes in 1905–6 to improve their working conditions. The city’s population grew from 7,500 in 1839 to 8,230 in 1840, 12,000 in 1849, 13,600 in 1854 and then to 33,347 in 1897, remaining at 32,500 in 1913. According to the 1897 census, Ukrainians formed the third largest minority (after Russians and Jews) in the city and the largest group, outnumbering Russian speakers in the rural settlements, like Komysh Buruny (a Crimean Tatar village re-settled by the 19th century with Ukrainian peasants), in the Kerch-Yenikale City Administration (see Table 1).

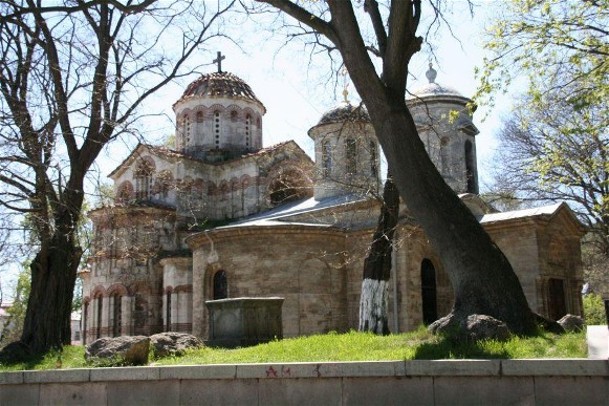

The Jewish identity in Kerch was maintained with the help of four synagogues: old (1837), Krymchak (1866), artisan (1869, elevated to synagogue in 1915), and new (main, 1875). Crimean Tatars attended their Kerch Mosque (built 1842–50). The Greeks attended Saint Athanasius the Great Church while the Armenians and Georgians had their churches. Roman Catholics had the Dormition of the Mother of God Cathedral (funded by the Italian community, built 1831–40). The Germans had their Lutheran Church (built in 1905, converted by the Soviets into the ‘Rodina’ movie theater, demolished in the 1990s for building materials). The Russians and Ukrainians went to the oldest Saint John the Baptist (the Precursor) Church (dated 8th, 9th, or 10th century Byzantine-style structure; in 1803, a 3-nave extension and a bell tower were added, re-built in 1840s, and other changes made in 1892); to the newer and main place of worship, the Holy Trinity Cathedral (built 1832–45, closed in 1931, demolished after the Second World War), and to the Dormition of Most Holy Mother of God Church (built 1903–7 in Komysh-Buruny).

1917–20. During the revolutionary years of 1917–20 Kerch passed from the imperial Russian control to the Russian Provisional Government (March 1917); to militant Bolsheviks with the assistance of a Bolshevik-manned warship from Sevastopol (6 January 1918); to German military who set up the Crimean government of General Suleiman Sulkevich (May 1918); to the Anglo-French coalition-supported Russian White Army (November 1918) led by General Anton Denikin (who, based in the Kuban, held Kerch to keep out the expansion of the Crimean Socialist Soviet Republic [April-June 1919] from taking the Kerch Peninsula) and then succeeded by General Petr Wrangel.

The Revolution of 1917 and Ukraine’s struggle for independence (1917–20) stimulated the awakening of Ukrainian self-consciousness in the Crimea. In Kerch a Ukrainian community called ‘Hromada’ was organized by Dr. Yelysei Voliansky of the garrison hospital, with 178 members, comprising medical staff, gunners, torpedo men and sailors from the garrison. As it expanded, it attracted workers from the metallurgical plant, civil servants, and shopkeepers. By July 1917 ‘Hromada’ had over 500 members and even ran its candidate, Rev. Dziubenko, for city council. The city newspaper began to publish articles on Ukraine and its liberation movement. In August it opened its bookstore on Vorontsov Street (the city’s main street), and gained popularity beyond Kerch; the Kuban Cossacks, who visited Kerch, were its frequent clients.

Following the October Revolution of 1917 and their brief occupation of Kerch (January–April 1918) the Bolsheviks tried to close down the ‘Hromada,’ but their provocations and threats to individuals failed. When the UNR and German forces entered the Crimea, the Kerch ‘Hromada’ military attacked the Bolsheviks and took control of the Kerch fort and city. On 28 April 1918, the Kerch fort batteries saluted the raising of the Ukrainian national flag. On 1 May 1918 a detachment of Ukrainian ‘Free Cossacks’ led a parade singing the Ukrainian national anthem. The disgruntled Bolsheviks celebrated separately, and tried to burn down the fort by setting the adjacent oil barges on fire, but the Ukrainian sailors moved them offshore to avoid this calamity.

By 1920, the White Army of Generals Anton Denikin and Petr Wrangel, who championed “the single, undivided Russia,” destroyed the Ukrainian ‘Hromada.’ They also used the Kerch metallurgical plant to make armored trains and built a runway to fly military aircraft. Kerch, the last city in the Crimea held by the Whites, was finally taken by the Bolsheviks in November 1920 to become part of the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic within the RSFSR.

The Soviet period. Following the First World War and the civil war the city resumed its growth in the late 1920s. The census of 1926 recorded the city of Kerch population of 34,579, with a slight decline in the number (and percent) of ethnic Ukrainians: 2,615 (7.6). The number of Russians increased to 23,210 (67.1), the Jews declined to 3,674 (10.6), as did the Crimean Tatars, 1,297 (3.7) and Greeks, 1,202 (3.5). Soviet industrialization involved collectivization of agriculture, the closure of churches, mosques and synagogues and the diversion of their resources for the expansion of various industries in the 1930s, notably iron ore beneficiation (the Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Complex, 1931–7), a coke-chemical plant, 3 blast furnaces at the Kerch Metallurgical Plant (1929), a thermal-electric power plant, a ship-repair facility (1938), as well as a cannery and cotton ginning plant. In 1933 Kerch also became home of the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Fishing and Oceanography. By 1939 its population had reached 104,500.

During the Second World War Kerch was occupied twice by Nazi Germany. The German 11th Army took it on 16 November 1941, but lost it on 30 December 1941 to the Soviet Army after it landed at the Komysh-Buruny beach (with great losses) and elsewhere, to hold the city for six months; Germans re-took it in May 1942, but were challenged and put down the remnants of the Soviet troops in the Adzhimushkai quarry. In pursuit of petroleum from Baku, they brought in an assembly (made by Krupp) for a railroad bridge over the Kerch Strait and began its construction. A Soviet military landing (with huge loss of life) south of Kerch at Eltigen (re-named Heroivske after the war) on 31 October 1943, then northeast of the city on 3 November 1943, and fierce battles on the Kerch Peninsula led to the re-take of Kerch by the Soviet Army on 11 May 1944. Using the German materials, the bridge was erected (by 3 November 1944), but collapsed (February 1945) when moving ice floes damaged supports. Earlier, battles raging four times through the city destroyed 85 percent of its buildings. Civilian losses during occupation (15,000 killed [mostly Jews and Krymchaks], 14,000 taken to Germany) and Soviet postwar deportation of the Crimean Tatars (18–20 May 1944) reduced the population of Kerch to 41,000 in 1945.

After the Second World War, Kerch was completely rebuilt. Initially, German prisoners of war played an important part in reconstruction. Plans were made in 1949 to re-build the collapsed bridge, but abandoned in 1950 in favor of a ferry in its place. The transfer of the Crimea from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954 facilitated its development: the Dnipro River water enhanced the city’s supply in 1971 via the North Crimean Canal. In 1973, the city was awarded the title Hero City and monuments were built to cultivate the memory of the ‘Great Patriotic War’. Indeed, the first monument to honor the heroes who died to liberate Kerch, the Obelisk of Victory, was erected in 1944, replacing the Stempkovsky Chapel on Mount Mitridat. Manufacturing was restored and diversified to include pipe-making, many kinds of machine-building and glass-packaging; shipbuilding was expanded (oil tankers, atomic ice-breaker). The city’s population grew from 95,000 in 1956 to 98,000 in 1959; the share of Russians increased to about 82 percent, Ukrainians to about 12 percent, while the Crimean Tatars were eliminated by deportation and others reduced to 6 percent. Population grew to 128,000 (1970), 136,000 (1972), 157,000 (1979) and 174,000 by 1989. During Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika period, organized religions revived and then diversified with the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence.

In Kerch, the Russian Orthodox church already had two churches functioning: the Saint Athanasius the Great Church (closed temporarily in 1923, then again in 1937, re-opened during German occupation in 1943 and remained open since), and the Dormition Church (built 1905–7, converted to a clubhouse in 1930, re-sanctified in 1943 and remained open since). Even so, they desired to open the 8th century Saint John the Baptist Church, which then served as a historic museum. In 1989 the city’s Commission on Culture and Education opposed its reactivation to avoid structural damage and retain it as the repository of lapidaries of the Kerch History and Archeology Museum. In 1990 despite similar recommendation by E. Yakovenko, director of the museum, a passionate argument by a local Russian activist E. Desiatov to revive the church activity caused the mayor, I. Kryvorotko, to re-convene the city council the next day; after more arguments, votes were cast by the deputies, and the majority voted to transfer this oldest standing church in the Crimea to the Russian Orthodox church.

Independent Ukraine. Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, the Kerch city council posted Ukrainian as the official language along with Russian and Crimean Tatar. In practice, Russian remained the lingua franca. Initially, elections to the city council were not party based, whereby former Russian-speaking Communist functionaries prevailed. With time the control of the city shifted to representatives of political parties. In Kerch, the Communist Party of Ukraine had the majority in 1997. By 2010, the mayor and, of the 50 members of the city council (a mix of administrators and business owners) 42 (or 84 percent) were members of the Party of Regions, who supported the official use of Russian.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union the large industries of Kerch were hard hit. Some adapted to new market conditions, others closed. For survival, the unemployed turned to subsistence farming and fishing, while pensioners sold their valuables to survive. The city’s infrastructure also deteriorated. Chaotic and gangster-like privatization ensued. As the economy stabilized, financial services and tourism gained importance. Even so, some Kerch residents worked for the Crimea’s integration with the Russian Federation. E. Desiatov, for example, opened his tourist enterprise (1994), but rather than facilitating travel abroad to buy and sell goods, as others did, he hosted young Russians largely from Moscow to experience the natural beauty of Kerch and the Crimea, ending with an open-fire meal and a toast: ‘for the Crimea with Russia.’

The city’s population growth slowed down (when deaths began to exceed births in 1991, but compensated until 1993 by net in-migration), peaked at 183,000 in 1993, then gradually declined (with aging population and net out-migration) to 179,000 (1995), 167,000 (1998), and 162,000 (2001). The 2001 census revealed the population of Kerch was 158,165 of which Russians numbered 124,430 (78.7 percent); Ukrainians increased to 24,298 (15.4), Belarusians declined to 1,795 (1.1), the returned Crimean Tatars numbered 1,635 (1.0), Tatars 383 (0.2), and the remaining others 5,624 (3.6 percent). With out-migration exceeding in-migration and deaths exceeding births, the city’s population continued to decline (January 1 of each year): 151,327 (2006), 147,269 (2010), to 144,626 (2014).

Having returned to the outskirts of Kerch, the Crimean Tatars demanded the return of their Kerch Mosque (closed in 1938, converted to a movie theater, then to the Nekrasov Library); it was re-opened in 1998 and designated by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Ukraine an architectural monument of local significance. The Jews, having been reduced to a small number, managed to organize in 1996 and had their remaining synagogue returned (originally the artisan house of prayer, built in 1869) to become an architectural attribute of the city. The Roman Catholic Dormition of the Mother of God Cathedral (built 1831–40, closed 1938, served as movie theater, was re-claimed as part of the Odesa-Simferopol diocese (established 2002). Evangelists (the Good Tidings Church), Seventh Day Adventists (2 houses of worship), and the Christian Source of Life Church were also established.

The Russian Orthodox church, re-named Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate, already had three active churches in Kerch. Others were opened, like the Saint Luke Church (sanctified in 2000, converted from a 1950s-built club house in Marat), the Dimitri Donskoi Church (sanctified in 2001, converted from a 1935-built club house in Kapkany) or newly built, like the Saint Andrew the First Called Church (built 2007–11 in the Komsomol Park; later, it facilitated Russian invasion in 2014 by hosting the Kuban Cossacks and then supported the erection of the monument to Petr Wrangel [2016]).

By contrast, Ukrainian cultural institutions in Kerch, catering mostly to those who came from mainland Ukraine, were difficult to establish. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate, formed its SS Peter and Paul parish, but was never able to get a permit for its church building; its faithful met at the priest’s residence for prayer. The SS Volodymyr and Olha parish of the Ukrainian Catholic church was registered in 2004; after it attained a permit and had its small church built (2010), its attendance increased from 20 to 50. The attitude of local functionaries and Russian-speaking population to Ukrainian-language activists in the ‘Prosvita’ organization became hostile. In 2000, for example, the local branch of ‘Prosvita’ applied for and obtained a permit to place a plaque and erect a monument to the native son of Kerch and poet who wrote for children, Ivan Lypa. After the plan to put up the already completed monument was announced in the Kerchenskii rabochii newspaper, E. Desiatov intervened (with an article in the newspaper) to stop this ‘shame’ of celebrating someone who served as minister in the Symon Petlura government ‘whose followers committed pogroms.’ As a result, the permit to put up the monument was cancelled and the plaque destroyed by the house owner. The subsequent disappearance of the monument to the Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin, Desiatov surmised, was vengeance by the ‘Prosvita’ members.

When part of Ukraine, Kerch was structurally enhanced. Oleh Osadchy, an able administrator (who came from the Donets Basin) was re-elected twice (2006, 2010) mayor (1998–2014). He brought good governance, revitalized transit by establishing trolleybus operations, re-developed city neighborhoods and beautified the city center (the Lenin Square [aka Square of Glory, pre-Soviet Predecessor Square] with many memorials, fountains [at the city theater, at city hall, at the bay shore, and elsewhere], reconstructed and enhanced the streets with trees, flower pots or decorative lamps and the entry to the city with sculptures) making its citizens proud. He approved (1998) the new Kerch coat of arms (which was recommended by Desiatov, researched in Saint Petersburg and devised by the artist Zhenia Morozova). It featured the Imperial crown (from Tsar Nicholas II, who visited Kerch in 1837), the Gryphon (symbolic of the Bosporus Kingdom), a key (for Russia to the Black Sea), and the Golden Star (Hero City) and profusely decorated the Karl Marx Street.

Russian occupation. In February 2014 the Russian Federation commenced the seizure of the Crimea. This began with anti-Ukrainian meetings and demonstrations, organized by Russian secret service. The first object of seizure was the Kerch ferry docks. The Ukrainian 501st battalion of marines and 127th battalion of coast guard stationed in Kerch were quickly surrounded and neutralized. Soon most of the Crimean servicemen in Kerch succumbed to Russian offers and switched sides. Mayor Osadchy, having refused to approve the raising of the Russian flag, was replaced.

The special population census taken on 14 October 2014 revealed the population of Kerch grew to 147,033. There was an influx of Russians 124,580 (or 84.7 percent of the city’s population) and a departure or concealment of some Ukrainians, down to 12,132 (8.25 percent) and Crimean Tatars 1,374 (0.93), whereas Tatars (not identified as Crimean) increased to 1,097 (0.75); since 2001 Belarusians continued their repatriation, declining to 996 (0.68) by 2014; 4,393 persons (2.99 percent) chose not to answer the ‘nationality’ question.

Pressure on Ukrainian organizations was particularly intense; many priests and faithful of the Ukrainian churches left for mainland Ukraine; in Kerch, as elsewhere in the Crimea, the Ukrainian Catholic church, to serve the remaining faithful, agreed to re-register (2016) as a Byzantine Catholic Church answering directly to the Vatican; the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (formerly Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate) was disallowed, its functioning disrupted.

The city was militarized with an influx of people from the Russian Federation. Industries were revitalized with strategic contracts. To enhance the link with mainland Russia, the Crimea Bridge, comprising a four lane highway and a separate double track railway, was built (2015–18 and 2015–19). The highway bridge was opened to traffic in 2018; the railway bridge, to passenger trains on 25 December 2019 and freight trains on 30 June 2020. Tourism from the Russian Federation was revitalized. Crimean minorities (other than Ukrainians) were offered funding to restore their houses of prayer.

Economy. On the eve of the Second World War Kerch was, after Sevastopol, the second most industrialized city in the Crimea. It had 169 enterprises which employed 42,000 workers. By the 1960–80s Kerch accounted for 20 percent of the industrial output and 75 percent of the fish catch in the Crimea. Formal employment in Kerch in 2017 (23,631 out of 81,168 working age people) reported by sectors as follows (in percent): manufacturing, 21.5; transportation and communications, 20.1; education, 18.1; medical services, 14.6; administration and defense, 6.9; utilities, 5.8; finance, 4.7; communal services; 3.5; wholesale and retail trade and repairs, 2.7; many of working age who did not respond to the survey were engaged in informal economy, mainly services.

The main branches of industry are: ferrous metallurgy, ship-building and ship repair, fishing and fish processing and canning. Other industries include the making of glass, building materials, plastics, machinery, clothing and food processing. Iron ore with vanadium and flux limestone were extracted nearby (see Kerch Iron-ore Basin) and beneficiated at the Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Complex. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and a drop in government orders for metal and ships, this processing plant cut back and then stopped its production; it is now dismantled.

The two largest enterprises are in 1) metallurgy and 2) shipbuilding. 1) the Kerch Metallurgical Plant (est 1900, the largest enterprise in the Crimea, had blast furnaces added in 1913, 1914), fixed armored trains for the Russian Volunteer Army in the Civil War, was nationalized in 1920, destroyed by fire in 1925, restored, and enlarged in 1930–32, re-built without blast furnaces after the Second World War. In independent Ukraine, it was privatized (1996) and then re-structured in 2002 into two enterprises. 1a) The Kerch Switch Plant, making cast iron and steel castings, and turnouts for industrial enterprises and mining and processing plants, main and underground tracks, urban transport routes [tram turnouts], spare parts and components for them), was recognized 2010 by National Business Rating as an industrial leader, provided best work conditions for 1,000 employees; after Russian annexation in 2014 it lost its clients in Ukraine, became the Kerch branch of Krasnodar Switch Company LLC. 1b) The Enamel & Co, making enamel kitchenware, plastic-ware and decals. 2) The shipbuilding and ship repair plant ‘Zaliv’ (est 1938, one of the largest in Eastern Europe, with two construction lines). Since 1945 until 1980 it built 800 vessels, including military frigates, oil tankers and oil platforms and, in 1988, the world’s first nuclear-powered icebreaking container ship ‘Severmorput’. In independent Ukraine, the plant was privatized in 2000, and began to produce civil ship hulls for companies in Greece, Netherlands, and Norway; from 1999 to 2014, the plant also produced vessels for servicing and supplying offshore oil and gas platforms, bulk carriers and container ships, a floating dock, a gas production platform and sections of chemical tankers; during the same period, more than 100 ships (mostly bulk carriers) were repaired. After Russian annexation (2014), the plant was re-registered under Russian ownership, and resumed production of civilian and military ships and sections for the Kerch Bridge; it was sanctioned by the US (2016), the EU (2018) and Canada (2019).

Other processing and machine building in Kerch include: the ‘KMZ KMK Metallurgical Plant’; the ‘PSZ KMPZ Vityaz’ (instruments, machinery); the ‘Kvartz Glass Factory KSZ’ (making glass, optics and instruments); a glass container plant; a building materials plant (making bricks, cement and fabricated products); petrochemical production and storage; two companies, ‘Rhodes’ and ‘Algeal,’ make plastic disposable tableware and packaging. Repair services are provided by the ‘Kerch Aircraft Repair Plant KeARZ’; marine services are provided by the ‘KMZ KMTP SV Fregat’ floating docks and ship repair, and the ‘KSRZ Iuvas-Trans’ floating docks and ship repair.

The food industry is dominated by fish processing and canning, making a large variety of fish products. The largest is ‘Prolyv’ (est 1873). Other plants include ‘Zvezda Rybaka,’ ‘Krymskii Bereg,’ and ‘Kerchrybkholod.’ Other food processing includes grain-milling products and cooking oil.

The light industry is represented by the ‘Kerch Garment Factory’ (est 1939, now an LLC) which sews children’s clothing, has a modeling center and online store. There is also a printing and publishing in Kerch.

Transportation and communication, the second most important activity, is represented by shipping, rail freight, local pipelines and trucking. Shipping is done through four ports. 1) The Kerch Commercial Port provides both freight and passenger service; in 2009, a ferry service was opened between Kerch and Poti (Georgia). 2) South of the city center, at Tsementna Slobidka, a port was dredged to accommodate fisheries, bulk commodities like cement and more recently enhanced to handle oil and petroleum products. 3) Farther south, the ice-free Komysh-Buruny Port, sheltered by the Komysh-Buruny Spit, was built in 1930s next to the Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Complex to ship iron nodules and flux to Mariupol (then called Zhdanov) and received coke and coal in return; in the post-Soviet period, the commodities changed to cement, clinker and grain; on the spit are docks and a fish-processing plant. 4) In the northeast end and narrowest part of the Kerch Strait, beyond other fish processing plants and docks, the Krym Port was built in 1953; it carried railway cars and automobiles between the Crimea and Krasnodar krai (Port Krym–Port Kavkaz) from 1954 until 2020, when the Kerch Strait Bridge replaced the ferry, so it now serves as a back-up.

Research and polytechnical education support fisheries, metallurgy and shipbuilding. These are: 1) the Southern Branch of the All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Fisheries and Oceanography (est. 1933); 2) the commercial ‘IuNIS Scientific Technical Center’ (est 1997, developing fish additives to food); and 3) the Kerch State Marine Technological University (reorganized in 2006 to include Odesa and Kherson branches; in the Soviet period it originated as a branch of the Kaliningrad Technical University of Fisheries). 4) The Crimean Engineering-Pedagogical University (Simferopol) has an educational and counseling office in Kerch; and 5) there was a small Kerch Branch of the Tavriia National University (Simferopol). Other institutions of higher technical education are 1) the Kerch Polytechnical College (formerly tekhnikum), 2) the Kerch Marine Technology College (formerly tekhnikum), 3) the Kerch Tekhnological Tekhnikum, 4) the G.K. Petrova Kerch Medical College, and 5) the Kerch College of Economics and Information Technologies.

General education is provided in the Russian language in 28 schools and 27 preschools. There are 2 music schools, 3 palaces of culture, 9 clubs, 3 movie theaters and 19 libraries.

There are 18 medical establishments in Kerch: 7 (including 3 hospitals) answer to the city, 8 to the Republic of Crimea and 3 (epidemiological and disinfection stations) to the national government. Kerch has 10 hotels, 11 tourist agencies, 23 banks, many restaurants and stores. Main tourist attractions are historic sites and some natural points of interest.

Culture. Kerch is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the Crimea. Within its present boundary there are the remains of six ancient cities, among them Myrmecium (according to some legends, it was home of Achilles of the Trojan War, whose soldiers used iron weapons to defeat their bronze-armed enemies; that city had the sarcophagus with a figure of Achilles, which was found in 1834, placed in the Kerch Museum, then re-located in 1851 to the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg), Tiritaka, Nymphaeum, and Panticapeum. Some 26 km west of the city’s limits, extending from the shores of the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea, stands the Cimmerian Wall, probably built by ancient Greeks in the 4th–3rd century BC and used to protect the Bosporan Kingdom. Archeological excavations in and near Kerch began in the 1830s, led by the Frenchman from Luxembourg, Paul DuBrux.

Historic sites include the ruins of the Panticapeum acropolis on Mount Mitridat with the Sarmatian burial chambers below the surface; excavation sites of the cities of Myrmecium, Nymphaeum, Panticapaeum, and Tiritaka; the nearby royal Scythian burial mound, Kul-Oba (400–350 BC, its golden artefacts preserved in the Saint Petersburg Hermitage and the State Historical Museum in Moscow), the royal burial chamber Tsarskyi kurhan (probably of King Levkon [389–349 BC], robbed in ancient times), the Melek-Chesmen kurhan (discovered in 1858, with burial chamber and dromos [passage] in the 4th century BC Bosporan Kingdom style, robbed in the past), and the Yuz-Oba kurhan (4th–3rd centuries BC, studied in 1858). Some artefacts from these and other sites have been preserved in the Kerch History and Archeology Museum (est 1826, with separate Lapidarium [a new building in the Kolonka neighborhood], pottery museum and golden pantry, with over 130,000 artefacts) reflecting the region’s past.

The city’s most impressive architectural monuments are: Demeter’s Vault with ancient Greek mythological frescoes (1st century AD), the Church of Saint John the Baptist (built in the 8th century in the Byzantine style on the foundations of a basilica [4th or 6th century], with murals from the 13th–14th century), the Yenikale fortress (1706), the Grand Mithridates Stairway (1833–40), and the Kerch Fortress (originally built in 1771, also called Fort Totleben, named after the military engineer, Eduard Totleben, appointed in 1859 to strengthen Kerch; it was re-built several times in the 1850s and later; de-militarized when part of independent Ukraine and made into a historical preserve). These monuments and sites are maintained as part of the Kerch Historical-Cultural Preserve (est 1987).

There are three major Second World War (Great Patriotic War) memorials built in the Soviet period: 1) the Obelisk of Glory on Mount Mitridat (the first to be erected in the Soviet Union, 8 October 1944, on the site of the Stempkovsky Chapel by dismantling it and using the stone from the dismantled Trinity Cathedral; the eternal flame was added nearby on 9 May 1959); here Kerch residents gather to celebrate Victory Day on May 9; 2) the Museum of History of the Defense of the Adzhimushkai Quarries (est 1966, complex completed with dramatic carvings of men on rock outcrop at entrance in 1982); and 3) the Museum of History of the Eltigen Landing (opened 8 May 1985, with rock sculpture of a giant sail). Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence small historical and cultural memorials were built: to Aleksandr Pushkin (1999), Taras Shevchenko (2001), Mithridates VI, the former governors Stempkovsky and Kherkeulidze as well as to the civilian victims of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ (2003), to Saint Luke (Archbishop of Simferopol and Crimea, known as Valentin Voino-Yasenetsky before becoming a widower and monk Luke [1919], founder of purulent surgery, laureate of Stalin Prize in medicine [1946], canonized by the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate in 1996), and others.

Cultural establishments include the Aleksandr Pushkin Drama Theater (1930s), the Kerch Art Gallery (opened 1968), and the Ethnographic Museum of Kerch Life (est 2009, featuring traditional mode of life of ethnic groups inhabiting the Crimea). There were, before 2014, over 30 performance groups, notably the ‘Kerchanka’ folk dance group, the exemplary violin ensemble, a jazz orchestra, and an Arts Lyceum with 6 ensembles.

There is also the Museum of Marine Flora and Fauna at the Southern Scientific-Research Institute of Fishing and Oceanography (displays since 1962). Natural attractions include: secluded Generals’ Beaches, 20 km NW of Kerch, below the coastal bluffs overlooking the Sea of Azov, with grottoes (some previously used by ancient Bosporan elite), therapeutic muds of Chokrak Lake (16 km NW of Kerch), and the Bulganak field of mud volcanoes (6 km N of Kerch). Mass media includes 6 newspapers and a magazine, 18 radio and 14 television frequencies; until 2013, when it was closed, the radio station ‘Breeze’ provided Ukrainian-language broadcasting, with programs from 10 leading stations of Ukraine.

City plan. Kerch developed on the western shore of the Kerch Bay, on the site of the ancient city of Panticapaeum. The old downtown, near the harbor, was the ancient agora; on the hilltop, overlooking the bay, was the acropolis (now in ruins). By 1900 Kerch grew well beyond the walls (which no longer stand) of its ancient predecessor to the west (the Kerch railway station), north and south. By 1938 Kerch had spread mainly 1) to the to the northeast, with a focus on the Kerch Metallurgical Plant, incorporating three settlements, each about 3 km apart a) Karantyn (beside the ruins of ancient Myrmekion), b) Kapkany, and c) Fort Yenikale; and 2) to the south, beyond a) Kerch Fortress on Cape Ak-Burun, which sheltered Kerch Bay as it faced Tuzla Island in the Kerch Strait (initially, it was Tuzla Spit, until a storm severed it from Cape Tuzla of Taman Peninsula in 1925), to b) Komysh Buruny (re-named, in 1948, Arshyntseve). The city was then divided into three city raions: central (Kirov), northeastern (Lenin), and southern (Ordzhonikidze), a division that lasted until 1988.

Following the post-Second World War reconstruction the city limits were extended in two directions. 1) To the northeast, along the Kerch Strait, they extend past Port Krym to Pidmaiachnyi on the Sea of Azov. 2) To the south, between Lake Chubashske and Komysh Buruny Bay of the Kerch Strait, to include (south of the ruins of Tyritake) the settlement of Rybna and the ‘Zalyv’ shipyard sheltered by the Komysh Buruny Spit, and south of it, next to the ruins of ancient Nymphaion, the beach and coastal settlement, Eltingen, re-named (1948) Heroivske. These extensions became parts of the Lenin and Ordzhonikidze city raions, respectively. Tuzla Island was also included in the city.

Presently on a map Kerch forms an irregular boomerang-like shape along the Kerch Strait. It extends from the southwest to the northeast about 26 km (measured in a straight line) or 55 km along the irregular, concave coast and inland from 5 to 10 km (in the middle, maximum width). It occupies an area of 109 sq km. Just beyond the city limits are six villages. In clockwise direction from the south, they are: Pryozerne, Ivanivka and Oktiabrske to the west, and Voikove, Bondarenkove, and Hlazivka to the north. Their population is mainly ethnically Ukrainian.

Within the city limits, over one fifth of the area is built up. Gardens, vineyards, and parks occupy another 2.5 percent of the area. The rest include archeological preserves, quarries, two tailing ponds, abandoned industrial sites and woodlots.

The railway line, approaching the city from the west, branches out: 1) to the east and 2) south, there serving industries and ports. The eastern line, with its main Kerch station, bypasses the old downtown on its way to Port Krym, providing spurs along the way to: 1) the city harbor and 2) the Kerch Steel Plant. The southern line winds its way to Arshyntseve, its Komysh Buruny Thermal Electric Power Station and ice-free port, with spur lines: 1) east, to the dredged marine fishing port at Tsementna Slobidka, 2) south, to the Zalyv Shipyard, and 3) southwest, to the former Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Complex. Other industries are located along the railway lines as well: on the east line, the Kirov Reinforced Concrete Plant (on the south side of the junction of the spur to the harbor) and (on the north side) the brick plant, pre-fabricated concrete (in north Karantyn), and fish processing plant (at Opasne). Along the southern line, southwest of the city center, is an asphalt plant, the Kerch gas utility, and then beyond the spur to Tsementna Slobidka, the ‘Kvarts’ glass works and the former ‘Albatros’ machinery plant.

The central, old part of the city includes Mount Mitridat, its slopes to the north, east and south, where streets conform to contours and then, on the plain to the north, a grid pattern aligned with the coast. The focus in the old city is the Saint John the Baptist Church and facing it, Lenin Square (so named in 1960s, before that, Tolstoy Square, and pre-Soviet, the Precursor Square), with other parks and squares enlarging it to what was formerly a small Turkish (18th century) urban center. From Lenin Square a stairway rises to the southwest up Mount Mitridat (named after Mithridates VI Eupator [120 to 63 BC], king of Pontus who challenged the Roman Empire), to the Obelisk of Glory and the ruins of the Panticapaeum acropolis.

From the vicinity of Lenin Square arterials lead in three directions: 1) to the northeast, Kirov Street (pre-Soviet Karantyn Street, as it follows the coast to Karantyn); 2) to the south, from Kirov Street, bypassing Lenin Square and associated parks along the shore as Admiral Passage, changing its name to Sverdlov Street (pre-Soviet Bosfor Street, the main street of the old Bosfor neighborhood at the southeast base of Mount Mitridat); and 3) inland, to the northwest, Lenin Street (pre-Soviet Vorontsov Street). Lenin Street forms a base line in the grid for several other major streets to the northeast that connect to the coastal Kirov Street.

Central Kerch has many institutions and commercial establishments. Around Lenin Square (with its parks and monuments to Vladimir Lenin and to the victims of the Second World War) in the northwest is the Pushkin Theater; on the southwest side, going south on Theater Street are the Assumption Roman Catholic Church, the former Kerch Institute for Daughters of the Nobility (now High School No. 2) with a monument to the child victims of the ‘Great Patriotic War’, the base of Grand Mithridates Stairway with monuments to Mithridates IV (on the northwest side), and the Kerch Picture Gallery (on the southeast side). On the south side, along Sverdlov Street (going southwest on its northwest side) is the Oceanography Museum, the Kerch City Court House, the City Cultural Center, the Aleksandr-Nevskii Church and the Kerch Historical-Archeological Museum; on the shoreline side of Sverdlov Street are parks with promenades, monuments (to Aleksandr Pushkin, to the sappers, to friendship of Ukraine and Russia, to the fish bounty of the sea, and to student soldiers who landed to liberate Kerch) and a playground with a Ferris wheel. Facing Lenin Square from the north is the main Kerch post office, with a Griffon monument in front of it and on the east side of Kirov Street is the ‘Furshet’ Market. Going north along Kirov Street is the Kerch City Hall; beyond it, the park-like Shevchenko Square with Taras Shevchenko monument and behind it the Christian Church ‘Source of Life’, and beyond the Melek-Chesme River, the Air Force Park with its monument. On the shoreline side of Kirov Street, beyond the market, is a stretch of parks with monuments, and a dock for ships (sailing to Yeisk, Kavkaz, Batumi and Poti); beyond it are ship repair docks and the old commercial port of Kerch with railway tracks serving the docks. West of Lenin Square, at the north base of Mount Mitridat, on Theater Street, is the Armenian Church, and west of it, facing a military cemetery to the west, the old Saint Athanasius the Great Church. The Central City Library and the Ukraina Movie Theater are on Soviet Street; the Central Market is between Proletarian Street and the canalized Melek-Chesme River (now called Prymorska River). Central Kerch has a mix of 2–5 story housing; small parks enhance the center’s livability.

West of the city center, within the central (Kirov) raion, the arterials turn west, re-orienting the street grid. At the city market, the Melek-Chesme River flows in from the west. There, the Marshal Yermelenko Street alongside it also turns west to become part of Highway E97 (going west); at the Shlagbaum Street intersection (where Highway E97 zigs south), Yermelenko Street becomes Train Station Highway and continues west beyond the city limits along the railway line. Reorientation of the grid also occurs on Lenin Street. At its major intersection (where the Holy Trinity Cathedral once stood), the Pyrohova Street (pre-Soviet Feodosiia Street) leads west to E97 west, while Samoilenko Street (pre-Soviet Urban Street) leads north, intersecting with Marshal Yermelenko Street (E97) going east to Port Krym or continuing north as Miroshnyk Street past the Planet Prosport Complex with two sports fields and a clinic on the west side.

Going west from Miroshnyk Street along Marshal Yermelenko Street, the land uses are mainly residential, but include some institutional and industrial. On the north side, is a soccer stadium (home of the Ocean Kerch Football Club, founded 1955 as Metalurh, 1976 as Okean, 2010 refounded) and then some industries and then the Kerch passenger railway station; on the south side, blocks of 4-story apartments, a small park with the Pyrohova Kerch Medical College and Hospital behind it, a neighborhood of town homes, a preserved woodlot, and in its southeast corner, the SS Volodymyr and Olha Church, the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Park Square, and behind it, the Kerch Transformer Station.

North of the city center two arterials lead to the east: the coastal Kirov Street and Highway E97, which bears different street names along the way. Kirov Street, beyond the railway tracks passes the Kerch port (south side) and a fish processing plant (north side), the ‘Fregat’ ship repair (south side) and the Komsomol Park (north side) which now includes the Saint Andrew (the First Called) Church on the park’s east side; beyond it are neighborhoods of 9-story apartments and schools, ending at Karantyn with its own street grid and individual housing; the remains of Myrmekion and its acropolis are at the Karantyn Point.

Similarly, on Highway E97, on the north side of the traffic circle where the arterial changes from Yermelenko to Gorky Street, is the inter-city bus depot and behind it, the Melek-Chesmen kurhan, surrounded by a complex of 4-story apartment buildings, and northeast of them, behind a mini-park, the Demeter’s Vault. To the east, crossing over the railway spur to the port, is the fish cannery (south side), wholesale market and court house (north side), then a strip of apartment neighborhoods with services (both sides). At a traffic circle, Gagarin Street splits off to the northeast through a large single-home residential area to the railway tracks and beyond them, the Adzhimushkai neighborhood with Saint John the Apostle Church, the Adzhimushkai Quarries Memorial Museum, and southeast of it, at the end of Scythian Street, the Tsarskyi kurhan (2.4 km north of Myrmekion). From the traffic circle, Gorky Street continues east to the Komsomol Park (south side), where the street name changes to General Petrov Street and then Voikov Street, flanked by high-rise apartment blocks with schools and parks of the Kolonka neighborhood, before passing old Karantyn (south side). Approaching the Voikov Kerch Metallurgical Plant is the Voikov Park (south side) with the Polytechnical Tekhnikum and the Voikov Factory Stadium in it, and the smaller Gagarin Park (north side), and near it, the new Lapidarium and the Kerch Services Professional Lyceum. Passing the metallurgical plant, the street name changes to Baltic Street, and beyond, in the Kapkany single home residential neighborhood, where the Dimitri Donskoy Church is located, it becomes General Kulakov Street. From Kapkany, Highway E97 turns north, bypassing Fort Yenikale and the Kerch fish processing plant as the Cimmerian Highway, to connect with the ferry at Port Kerch. Other streets lead to the fort, the fish processing plant, and beyond Port Kerch to the neighborhoods of Zhukovka, Gleiki, and Podmaiachnyi on the Sea of Azov coast.

To the south, beyond Mount Mitradat, Sverdlov Street reaches a traffic circle. The arterial continues south as the Komysh-Buruny Highway, with the Marat neighborhood of 4-story apartments on the west side and beyond it, to the west, the Saint Luke Church. The arterial then passes the eastern side of the Tavriia neighborhood of 5–10 story high apartments that extend west. On the east side of the arterial is the trolleybus depot and beyond it, the marine fishing port, fuel and the Tsementna Slobidka cement depot. From here the arterial passes over the newly built rail and highway going to the new Kerch Bridge, past the Sonechnyi neighborhood, bypassing the orchards and elevated grounds with scrub forest and Fort Kerch to the east and Soldatska Slobidka woodlot to the west, past the Partyzanskyi quarry settlement and the Yuz-Oba mound to the west and the television transmission tower to the east.

At Arshyntseve the thoroughfare is called Ordzhonikidze Street. To the east, overlooking the Kerch Strait is a newer Seven Winds neighborhood with town homes and the Dormition of Mother of God Church. Ordzhonikidze Street then passes, on the east side, the Kerch State Marine Technological University, the Hope Child Therapy Center, the Pushkin Youth Park of Recreation and Culture with the second campus of the Kerch State Marine Technology University; on the west side, a hospital and the Metallurg Stadium (built 1936, now neglected); towards the end of Arshyntseve (east side) the ancient remains of Tiritaka and beyond it, the Komysh-Buruny Thermal Electric Power Station and the ‘Zalyv’ Shipbuilding Plant; and (west side), the Komysh-Buruny Transformer Station, the remains of the Komysh-Buruny Iron-ore Enrichment Plant and then, what remains of Churbashske Lake, tailings ponds on both sides of the road and a wastewater treatment plant. Except for a few apartment buildings, most of the housing in Arshyntseve is individual with gardens.

Beyond Arshyntseve, the thoroughfare name becomes the Heroes of Eltigen Highway, turning east to Heroivske; near the Komysh-Buruny Point, the open ground holds the remains of the ancient Nimphei and on high ground, two light houses; along the road is a recreational settlement with a fine beach, rest homes and a grand memorial to the Eltigen landing heroes.

Transportation. City transit consists mainly of buses and microbuses. Streetcars operated in 1935–41 (from the city center to the Voikov Kerch Metallurgical Plant). When part of independent Ukraine, trolley buses were added (first line in 2004, from city center to Tsementna Slobidka; second line added in 2007, from the city center to the Kerch Metallurgical Plant, and in 2009, from city center to the Kerch railway station; an extension was proposed from Tsementna Slobidka to Arshyntseve). Suburban trains also operated between Port Kerch in the northeast and Arshyntseve in the south, with 4 to 6 stations in between. After the construction of the Kerch Bridge from Tsementna Slobidka to Tuzla Island, the passenger traffic by rail was re-oriented so that a new (now main) station for inter-city train travel, ‘Kerch Yuzhnaia’, was built approaching the bridge in the Soldatska Slobidka woodlot. The new E97 (M17) 4-lane divided highway to the bridge, with an interchange to the ‘Kerch Yuzhnaia’ station, also cuts through the former woodlot from the west.

Air transport was provided at the Kerch Airport, located within the city limits 2 km west of the Kerch train station. At its peak, it provided 8–10 flights per day within the Soviet Union. Its upkeep deteriorated after 1990, a revival was attempted in 2005, but was bankrupted and ceased operation in 2008. This airport is sometimes confused with another former strategic bomber airport located 14 km to the west-northwest, 5 km NW of the town of Baherove (2014 pop 3,900). The Baherove Polygon, est. 1947, was a strategic bomber airport for training crews to deliver nuclear bombs, with practice runs to Semipalatinsk, where initially dummies and then real atomic bombs were dropped, returning planes washed off and residue collected into nuclear waste storage. Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, the airport was de-commissioned and its structures dismantled for building material. The secluded beaches to the north on the Sea of Azov were named Generals’ Beaches, where visiting generals were taken for relaxation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Volia, M. ‘Ukraïns'ka hromada v Kerchi,’ Ukraïns'ke slovo no. 55 (Kyiv 1941)

Slavich, S. Gorod-geroi Kerch. Ocherk-putevoditel' (Simferopol 1976)

Kyslyi, O. ‘Kerch,’ in Entsyklopediia istorii Ukraïny, vol 4 (Kyiv 2007)

Krymska, R. ‘Zruinovani khramy Kerchi’ Kryms'ka svitlytsia no 47 (Kyiv 2018)

Desiatov, E. Kniga o Kerchi v khronike odnoi zhizni (Simferopol 2019)

‘Karta Kerchi, Kryma,’ Mapa Ukraïny https://kartaukrainy.com.ua/Kerch

‘Podrobnaia karta goroda Kerch,’ Karty Ukraïny https://euro-map.com/karty-ukrainy/kerch/podrobnaya-karta-goroda-kerch.jpg

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2023.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)