Galicia

Galicia (Ukrainian: Галичина; Halychyna). A historical region in southwestern Ukraine. Its ethnic Ukrainian territory occupies the basins of the upper and middle Dnister River, the upper Prut River and Buh River, and most of the Sian River, and has an area of 55,700 sq km. Its population was 5,824,100 in 1939. The name is derived from that of the city of princely Halych.

Location and territory. Galicia lies in the middle of the European landmass between the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea, to which it is linked by the rivers Dnister and Prut, and the Buh and Sian respectively. It is linked to the rest of Ukraine by land routes only. It is bounded by Poland in the west, Transcarpathia and the Lemko region in the southwest, Bukovyna in the southeast, Podilia in the east, Volhynia in the northeast, and the Kholm region in the northwest. Its location on the crossroads to the seas led its expansionist foreign neighbors, especially Poland and Hungary, to strive repeatedly to gain control of Galicia.

Galicia's location protected it from the incursions of Asiatic nomadic peoples and facilitated contact with the rest of Europe. After the demise of Kyiv as the capital of Kyivan Rus’ and the decline of the Varangian route, the main trade route linking the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea and Byzantium passed through Galicia. Because of its distance from the Eurasian steppe, medieval Rus’-Ukrainian statehood survived there as the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia for another century after the sack of Kyiv by the Mongols in 1240. The principality provided refuge to the people from other parts of Rus’ who had fled the Mongol invasion. It thus became a reservoir of Ukrainian population, much of which later remigrated to the east. With the decline of commerce in the Black Sea Basin in the 16th century, Galicia lost its importance as the link with the Baltic. Its peripheral role vis-à-vis developments in Ukraine during the period of the Hetman state rendered it relatively insignificant.

Only the southern, natural frontier of Galicia—shaped by the Carpathian Mountains—remained unchanged. The rulers of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia had extended the eastern frontier past the Zbruch River and into the steppe; at one time (end of 12th century), they ruled lands as far south as the lower Danube River. Under Polish rule (1340–1772) Galicia constituted first Rus’ land (Regnum Russiae) and then from 1434 Rus’ voivodeship (palatinate) and the western part of Podilia voivodeship.

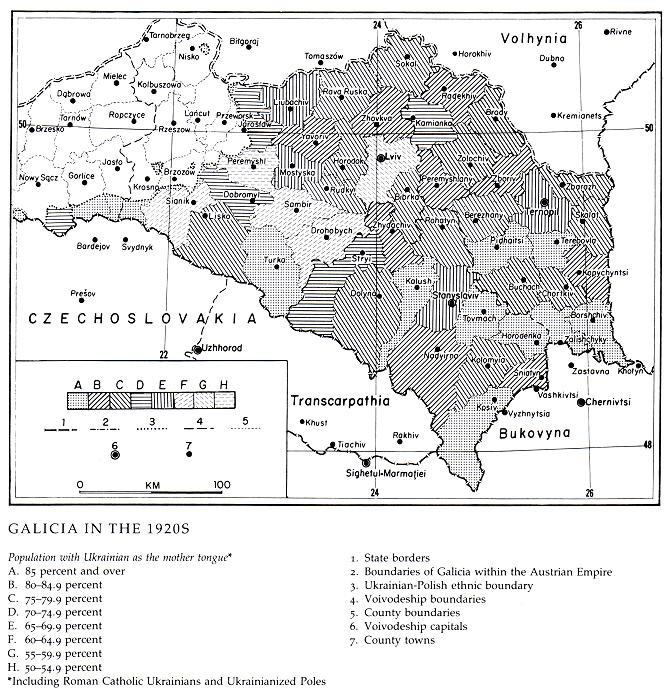

Under Austrian rule (1772–1918), Galicia was bounded in the east by the Zbruch River, and in the southeast, as it had been under Poland, by the Cheremosh River and the Dnister River. After the final partition of Poland in 1795 and territorial adjustments in 1809 during the Napoleonic wars, the administrative territory of Austrian Galicia also encompassed the western, Polish ethnographic part of Galicia—the area west of the jurisdictional boundary between the Lviv and Cracow higher crown land courts, which ran along the western limits of Sianik, Brzozów, Peremyshl, and Jarosław counties. Thus, Galicia embraced almost all the territory of the former Rus’ voivodeship, the southern part of Belz voivodeship, and small parts of Podilia voivodeship and Volhynia voivodeship, as well as some Polish ethnic lands. From 1787 to 1849 and again in 1859–61, Bukovyna was also administratively part of Galicia. From 1809 to 1815, the Ternopil region was occupied by Russia. The Western Ukrainian National Republic (1918–19) encompassed all of Ukrainian Galicia and, for a short time, the Ukrainian parts of Bukovyna and Transcarpathia. Under interwar Poland Ukrainian Galicia consisted of Lviv, Stanyslaviv, and Ternopil voivodeships. During the Nazi occupation (1941–4) it constituted the so-called Galicia district of the Generalgouvernement. In 1945 the west and northwestern borderlands of Ukrainian Galicia became part of Poland. The remaining territory was divided among four Soviet oblasts: Lviv oblast, Drohobych oblast (incorporated in 1959 into Lviv oblast), Stanyslaviv oblast (renamed Ivano-Frankivsk oblast in 1962), and Ternopil oblast.

Physical geography. Galicia is not a biotope, but consists of several natural regions: (1) the Carpathian Mountains; (2) the upper Sian region and Subcarpathia; and (3) the upland chain of Roztochia, Opilia Upland, Podilia, and Pokutia, which are separated by the Buh Depression from the southern fringe of the Volhynia-Podilia Upland. No other part of Ukraine has such a large variety of landforms (mountains, foothills, plateaus, and glacial depressions) in so small an area. Galicia's climate changes gradually from maritime in the northwest to continental in the east, mountain in the south, and Black Sea coastal in the southeast. There are corresponding vegetation zones: mountain forest and alpine meadow in the Carpathians, mixed forest in the west, and forest-steppe in the east. The eastern perimeter of the beech and fir forests runs through Galicia.

Prehistory. The oldest inhabitants of Galicia migrated into the Dnister River Basin from southern Ukraine during the Middle Paleolithic Period. The remains of a few settlements of the Mousterian culture (Bilche-Zolote, Bukivna, Zalishchyky-Pecherna, Kasperivtsi) have been uncovered there. Upper Paleolithic Aurignacian peoples relatively densely populated the basin between present-day Ivano-Frankivsk and Bukovyna, as well as southern Podilia. In the Mesolithic Period, northern Galicia between the Sian River and the Buh River was sparsely populated. In the Neolithic Period and Eneolithic Period, the northeast was inhabited by agricultural tribes of the so-called Buh culture. The Dnister Basin and part of western Podilia were inhabited by people of the Trypillia culture. The first migrating peoples from Silesia arrived, bringing with them pottery decorated with linear bands (see Linear Pottery culture). They were followed by seminomadic Nordic tribes of the Corded-Ware culture. A Nordic tribe that buried its dead in stone slab-cists settled in the Buh River Basin and spread into western Podilia.

In the Bronze Age, seminomadic peoples from the west forced a part of the autochthons in the Buh Basin to resettle in Polisia. Later, they penetrated into the region between the Dnister River and the Carpathian Mountains, where they came into contact with bronze-making tribes from Transcarpathia, and a mixed variant of the Komariv culture arose. In the middle Dnister Basin the Trypillia culture continued. In the 13th and 14th centuries BC, the first wave of the ancestors of the western proto-Slavs from Silesia penetrated into the lower Sian Basin; these tribes of the Lusatian culture occupied the western bank of the Sian River as far north as its confluence with the Tanew River.

In the Iron Age, agricultural tribes migrated back from Polisia into the upper Buh Basin and gave rise to the Vysotske culture. In the Dnister Basin the Thracian Hallstatt culture developed. In western Podilia, the so-called Scythian Ploughmen, who were most likely proto-Slavic tribes of the Chornyi Lis culture, made their appearance. At the end of the La Tène period, a second wave of western proto-Slavs, the Venedi, penetrated into the Dnister Basin and western Podilia. The Lypytsia culture arose; it is perhaps connected with the Getae who settled in the upper Dnister Basin, particularly after the Roman occupation of Dacia.

Galicia in the era of European tribal migration (AD 300–700) is not well known; a few proto-Slavic hamlets with gray, wheel-turned pottery and barrows with the cremated remains of the ancestors of the Tivertsians have been uncovered. Many archeological remains of the Princely era have been found, however: eg, fortified towns, settlements, burial grounds, architectural remains (the ruins of the Dormition Cathedral and other churches in princely Halych and Krylos), and the Zbruch idol. Evidence of foreign in-migration can be found in various localities: eg, ancient Magyar barrows near Krylos, Varangian barrows in the ancient town of Plisnesk, caches of Varangian arms, medieval foreign coins, and Cuman stone baby.

History

The Princely era. In the second half of the first millennium AD, the Buh River, Sian River, and Dnister River basins were inhabited by tribes of Buzhanians, Dulibians, White Croatians, and Tivertsians. Their fortified towns—Terebovlia, Halych, Zvenyhorod, Peremyshl, and others—flourished because of their location on trade routes linking the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea and Kyiv with Cracow, Prague, and Regensburg. This region was first mentioned in the medieval chronicle Povist’ vremennykh lit (Tale of Bygone Years), which described Grand Prince Volodymyr the Great's war with the Poles in 981 and his annexation of Peremyshl and the Cherven towns to Kyivan Rus’. In 992, Volodymyr marched on the White Croatians and annexed Subcarpathia. Thus, by the end of the 10th century all of Galicia's territory was part of Kyivan Rus’, and it shared its political, social, economic, religious, and cultural development.

After the death of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, Kyivan Rus’ began to fall apart into its component principalities. From 1084 Yaroslav's great-grandsons, Riuryk Rostyslavych, Volodar Rostyslavych, and Vasylko Rostyslavych, ruled the lands of Peremyshl, Zvenyhorod, and Terebovlia. Volodar's son, Volodymyrko Volodarovych, inherited the Zvenyhorod principality in 1124, the Peremyshl principality in 1129, and Terebovlia principality and Halych land in 1141; he made princely Halych his capital. Volodymyrko's son, Yaroslav Osmomysl, the pre-eminent prince of the Rostyslavych dynasty, enlarged Halych principality during his reign (1153–87) to encompass all the lands between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dnister River as far south as the lower Danube River. Trade and salt mining stimulated the rise of a powerful boyar estate in Galicia. The boyars often opposed the policies and plans of the Galician princes and undermined their rule by provoking internal strife and supporting foreign intervention. When Volodymyr Yaroslavych, the last prince of the Rostyslavych dynasty, died in 1199, the boyars invited Prince Roman Mstyslavych of Volhynia to take the throne.

Roman Mstyslavych united Galicia with Volhynia and thus created the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. It was ruled by the Romanovych dynasty until 1340. The period from 1205 to 1238 in the Galician-Volhynian state was one of further intervention by Hungary and Poland, of internal strife among the appanage princes and the boyars, and hence of economic decline. During the reign of Danylo Romanovych (1238–64), however, Galicia-Volhynia flourished, despite the Mongol invasion of 1240–1. Danylo Romanovych promoted the development of existing towns and built new ones (Lviv, Kholm, and others), furthered the status of his allies (the burghers), and subdued the rebellious boyars. Using diplomacy and dynastic ties with Europe's rulers, he strove to stem the Mongol expansion. The Galicia-Volhynian state flourished under Danylo Romanovych's successors. In 1272 Lviv became the capital, and in 1303 Halych metropoly was founded. But resurgent boyar defiance, the Mongol presence, and the territorial ambitions of Poland and Hungary took their toll. The Romanovych dynasty came to an end in 1340 when boyars poisoned Prince Yurii II Boleslav, and rivalry among the rulers of Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, and the Mongols for possession of Galicia and Volhynia ensued.

The Polish era. The struggle lasted until 1387. In 1340 King Casimir III the Great of Poland attacked Lviv and departed with the Galician-Volhynian regalia. A boyar oligarchy ruled Galicia under the leadership of Dmytro Dedko until 1349, when Casimir again invaded and progressively occupied it. In 1370 Casimir's nephew, Louis I the Great of Hungary, also became the king of Poland; he appointed Prince Władysław Opolczyk in 1372 and Hungarian vicegerents from 1378 to govern Galicia. After the marriage of Grand Duke Jagiełło of Lithuania and Louis's daughter, Queen Jadwiga of Poland, and the resulting dynastic union in 1386, an agreement was reached whereby Galicia and the Kholm region were acquired from Hungary by Poland, and Volhynia became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Under Polish rule, Galicia was known at first as the ‘Rus' land’ or Red Rus’ and was administered by a starosta, or vicegerent, appointed by the king. Roman Catholic dioceses were established in Peremyshl, Halych, and Kholm and were granted large estates and government subsidies. In 1365 a Catholic archdiocese was founded in Halych; it was transferred to Lviv in 1414. In the early 15th century, the region was renamed Rus’ voivodeship. Its capital became Lviv, and it was divided into four lands: Lviv, Halych, Peremyshl, and Sianik; in the 16th century, the Kholm region was also incorporated. In 1434, Rus’ law, based on Ruskaia Pravda, was abolished in Galicia and replaced by Polish law and the Polish administrative system. Land was distributed among the nobility, who proceeded to build up latifundia and to subject and exploit the peasants.

Major social changes occurred in Galicia. Boyars who refused to convert to Catholicism forfeited their estates. Many resettled in the Lithuanian lands; those who did not became impoverished, déclassé petty gentry and, with time, commoners. Certain boyars received royal privileges; they gradually renounced their Orthodox faith and stopped speaking Ukrainian, and became instead Polonized Catholics. The tendency to assimilate permeated all of Galicia's upper strata and was particularly prominent in the second half of the 16th century; by the end of the 17th century most of the Ukrainian nobility had become Polonized. At the same time Ukrainian merchants and artisans were deprived of their rights by the now favored Polish Catholic burghers who colonized the towns and received official positions and privileges granted solely to them by Magdeburg law. Polish government circles encouraged the inflow of Polish and foreign nobles and Catholic peasants into Galicia. The number of Poles, Germans, Armenians, and (later) Jews increased in the towns, where they established separate communities. The government's discrimination and limitations imposed by the guilds on the Ukrainian burghers provoked them to form brotherhoods to defend their rights towards the end of the 16th century.

In the 16th century corvée was introduced in the Polish Commonwealth. This excessive exploitation of peasant labor, which in many cases became actual slavery, led to peasant uprisings, among them the Mukha rebellion of 1490–2. Many peasants also escaped from the oppression to the steppe frontier of central Ukraine.

The Orthodox church, which had the support of the Ukrainian masses, had played an important role in Galicia. Yet the separate existence of Halych metropoly had been opposed from 1330 on by the metropolitans of Kyiv, who resided in Moscow. Halych metropoly therefore had no hierarch in the years 1355–70 and was abolished in 1401. Halych eparchy had no bishop from 1406 to 1539. At the end of the 16th century, in response to the Roman Catholic threat as well as the Reformation, a Ukrainian Orthodox religious and cultural revival began. The defense of Ukrainian interests was assumed by the aforementioned brotherhoods. One of the first was the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood, which existed as early as 1463, but whose earnest activity began in the 1580s, when it received Stauropegion status and founded a school (Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School), printing press (Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press), and hospital. Brotherhoods were founded in many other towns in Galicia using the one in Lviv as the model. Because of the brotherhoods, Galicia became an important center of Ukrainian cultural and religious life. The Lviv brotherhood, for example, nurtured such major Ukrainian figures as Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, Yov Boretsky, Yelysei Pletenetsky, Zakhariia Kopystensky, and Petro Mohyla.

After the 1596 Church Union of Berestia established the Ruthenian Uniate church, a long period of bitter internal strife between the Ukrainian Orthodox opponents of the union and its Uniate supporters ensued. (See History of the Ukrainian church and Polemical literature.) The Orthodox church lost its official status, which was not restored by the Polish king until 1632, and Galicia's role as the bastion of Ukrainian Orthodoxy was eclipsed. When the efforts of the leaders of the Hetman state to unite all the Ukrainian territories failed, the Orthodox hierarchs in Galicia and the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood accepted the church union, and in 1709 Uniate Catholicism became the only faith practiced by Galicia's Ukrainians.

Under Polish rule, many Ukrainians in Galicia who opposed the Polish state's and nobles' restrictions, interdictions, and oppression fled to the east, where they participated in the organized life and events of central and eastern Ukraine and the Zaporozhian Cossacks. (Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, for example, was from Galicia.) When Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky's army entered Galicia in 1648, 1649, and 1655 during the Cossack-Polish War, Galicia's Ukrainians organized the Pokutia rebellion against the Poles in 1648, joined Khmelnytsky's forces, and many retreated with them. After the war there were other manifestations of support for pan-Ukrainian political unity by Galicia's Ukrainians, but not on a mass scale. Galicia remained primarily a theater where the Cossack and Polish armies clashed; consequently, much of its population fled and settled in the Hetman state and Slobidska Ukraine.

In the Polish era, popular reaction to Polish rule and oppression in Galicia also took the form of social banditry. The brigands, called opryshoks, were particularly active in Subcarpathia and Pokutia from the 16th to the 19th century; their most famous leader was Oleksa Dovbush. From the second half of the 17th century, Poland experienced a series of wars and political, social, and economic crises leading to a general weakening of the regime that its neighbors (Austria, Prussia, and Russia) exploited. In 1772 the first partition of Poland occurred, and Galicia was annexed by the Austrian Empire.

The Austrian era. Austria laid claim to Galicia on the grounds that its empress, Maria Theresa, was also the queen of Hungary, which had occupied the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia in 1214–21 and 1370–87. The new Austrian province, called the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, had an area of some 83,000 sq km and around 2,800,000 inhabitants (in 1786). This artificial union of ethnic Ukrainian lands (with huge Polish latifundia) and Polish lands gave rise to constant disputes between the Poles and the Ukrainians under Austrian rule.

During their reigns, Austria's Maria Theresa (1740–80) and Joseph II (1780–90) introduced reforms to regulate landlord-peasant relations and improve the education of the clergy. In 1786 Austrian codes replaced Polish law and the dietines were replaced by an assembly of estates composed of the magnates, nobility, and clergy, which had no real powers. All the power was placed in the hands of the Austrian bureaucracy and the imperial governor in Lemberg (Lviv). In 1782, personal subjection of the peasants was abolished and serfdom was introduced, whereby the peasantry received certain personal and property rights; this, however, was not well enforced following Joseph's death.

In general, Galicia under Austrian rule was an undeveloped and backward agricultural province that provided food products and conscripts for the empire. The new state boundaries had cut it off from the old trade routes and natural markets, resulting in the decline of its towns. But Austrian rule proved favorable to the Ukrainians' religious life and education. In 1774, the Uniate church was officially renamed the Greek Catholic church; it and its clergy were granted the same rights and privileges as the (Polish) Roman Catholic church. Halych metropoly was reinstated in 1807 with its see in Lviv; it consisted of Lviv eparchy and Peremyshl eparchy. A Greek Catholic seminary, the Barbareum (1774–84), was founded in Vienna by Maria Theresa to give the clergy a proper education. The Greek Catholic Theological Seminary in Lviv was founded in 1783, and a special school, Studium Ruthenum (1787–1809), was established at Lviv University (founded in 1784) to train candidates for the priesthood who did not know Latin. These institutions prepared the future leaders of the Ukrainian cultural and national revival in Galicia, which occurred despite the fact that under the regime of State Chancellor K. von Metternich Austrian policy towards cultural and social emancipation in outlying provinces had changed for the worse. Under Leopold II, Ukrainian primary schools were abolished where Polish or German ones existed; by 1792 instruction in Ukrainian and Greek Catholic religion was very limited; and in 1812 compulsory education, introduced by Joseph II, was abolished. Lectures at Lviv University (which was closed from 1805 to 1817) were given in German and Latin, and Polish was the language of the primary schools. To counteract these developments, the church under Metropolitan Mykhailo Levytsky began founding Ukrainian-language parochial schools, which were approved by the emperor in 1818.

Under the impact of Romanticism and developments in Russian-ruled Ukraine and in other Slavic countries, a Ukrainian cultural and national renaissance began in Galicia in the 1820s. It was initiated by the seminary students Markiian Shashkevych, Yakiv Holovatsky, and Ivan Vahylevych, who were known as the Ruthenian Triad; they published the first Galician Ukrainian miscellany, Rusalka Dnistrovaia (The Dnister Water Nymph), in 1837. This renaissance reached it apogee in the Revolution of 1848–9 in the Habsburg monarchy. On 22 April 1848 Governor Franz Stadion announced the abolition of serfdom in Galicia on the basis of an imperial decree. In May, elections to the first Austrian parliament were held. Thirty-nine Ukrainian deputies were elected, and they soon began demanding social reforms and the division of Galicia along national (Ukrainian and Polish) lines.

The main representative of Galician Ukrainian national aspirations became the Supreme Ruthenian Council, which was founded in Lviv in May 1848. In its manifesto, the council proclaimed the unity of Galicia's Ukrainians with the rest of the Ukrainian people and demanded the creation of a separate crown land (province) in the Austrian Empire consisting of the Ukrainian parts of Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia. It published the first Ukrainian newspaper, Zoria halytska. Its representatives participated in the Slavic Congress in Prague, 1848, where the Ukrainians were recognized as a separate people. The council also organized a national guard, the People's Militia, and the Ruthenian Battalion of Mountain Riflemen. The existence of the council challenged the Polish claim that Galicia was part of Poland, and Polish leaders tried to undermine the council's position by creating a pro-Polish body consisting of nobles and Polonophile intellectuals—the Ruthenian Congress, which published the newspaper Dnewnyk Ruskij. During the Revolution of 1848–9 in the Habsburg monarchy, two cultural and educational institutions, the People's Home in Lviv and the Halytsko-Ruska Matytsia society, were founded, and the Congress of Ruthenian Scholars was held.

The various political and cultural activities ended with the suppression of the revolution, aided by the intervention of the Russian army in Hungary. The government of Emperor Francis Joseph I (1848–1916) tightened its grip throughout the Austrian Empire, re-established centralized rule, and introduced neoabsolutist policies. The Supreme Ruthenian Council was forced to dissolve in 1851. The Polish leaders in Galicia came to an agreement with the government whereby in exchange for their support they would have a free hand in administering the province. The devoted servant of Vienna, Agenor Gołuchowski, was appointed governor (from 1865 vicegerent) of Galicia in 1849; he governed, with a few interruptions, until 1875. Gołuchowski was opposed to all Ukrainian national aspirations and Galicia's territorial division. He filled the ranks of the civil service in Galicia with Poles and Polonized Lviv University. The actions of the government disillusioned a section of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and contributed to the growth of the Russophiles who claimed an affinity between the language of Galicia's Ukrainians and Russian. Their clerical-conservative leaders initially had a general, vague sympathy for tsarist Russia. These Old Ruthenians, as they called themselves, cultivated a macaronic, artificial idiom called yazychiie by its opponents and opposed the use of the Ukrainian vernacular, which was being promoted by their opponents, the Ukrainophile Populists. The Russophiles took control of the Halytsko-Ruska Matytsia society, the Stauropegion Institute, and the People's Home in Lviv, and created the Kachkovsky Society in 1874. They also published the newspaper Slovo (Lviv), the popular journal Nauka, the semimonthly Russkaia rada and Besieda, and other periodicals.

The Young Ruthenians—the young, secular intellectuals of Galicia, many of whom were teachers—organized the Populist movement in reaction to the cultural and political orientation of the Russophiles. They believed in the existence of a Ukrainian nation and considered themselves to be part of it, and they championed the use of the vernacular in schools and in literature. They maintained close ties with intellectuals in Russian-ruled Ukraine, including Panteleimon Kulish, Mykola Kostomarov, Oleksander Konysky, Mykhailo Drahomanov, Volodymyr Antonovych, and Mykhailo Hrushevsky. Inspired by the ideas expressed in the poetry of Taras Shevchenko, the ideology of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, and the work of the Hromada of Kyiv, the Populists organized the Ruska Besida cultural society in 1861, the Prosvita educational society in 1868, and, with the co-operation and financial aid of Ukrainians under Russian rule, the Literary Shevchenko Society in Lviv (later the Shevchenko Scientific Society) in 1873. They began publishing various periodicals, including the widely read journal Pravda, Dilo, and Zoria (Lviv). In the late 1870s a bitter struggle arose between the Russophile and Populist camps, in which the latter, supported by the students (among them Ivan Franko and Mykhailo Pavlyk) and the majority of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, emerged victorious. Thereafter the Russophiles lost most of their popular support and became peripheral to cultural developments. The support given to the Populists by leaders from Russian-ruled Ukraine, especially Drahomanov, helped secure their victory.

After 10 years of neoabsolutism, the constitutional period began in the Austrian Empire in February 1861, when the emperor issued a special patent creating a bicameral central parliament—consisting of a house of lords and a house of representatives—and provincial diets. Initially representatives to the central parliament were designated by the provincial diets, but from 1873 they were elected by four curiae (see Curial electoral system): the large landowners, chambers of commerce, municipalities, and everyone else, primarily rural communities. In 1897 a fifth curia was created in which virtually every literate male could vote, and in 1907 the curiae were abolished and universal male suffrage was introduced. Greek Catholic bishops were ex-officio members of the upper house. In the lower house the number of Ukrainian members varied, the highest being 49, in 1861, and the lowest 3, in 1879. Even though the Ukrainians constituted half of the population of Austrian Galicia, their share in the diet was never more than a third, and often much less, owing to Polish control of the provincial administration and to electoral manipulation. The Ukrainian members of the central parliament and the Galician diet (in Lviv) constantly demanded the administrative and political division of Galicia along national lines, universal suffrage instead of the curial system, the expansion of the Ukrainian secondary-school network, and the creation of a Ukrainian university in Lviv.

After serfdom was abolished in 1848, the peasantry owned only tiny subsistence holdings. Until 1900, up to 40 percent of the arable land remained in the hands of the large landowners. The gentry claimed ownership of pastures and forests and the peasants no longer had the right of use, which they had previously according to the traditional ‘servitudes’, but now had to pay for their use. The Polish nobility strongly opposed any improvement of the peasants’ condition and the equitable distribution of land. As their population rapidly increased, the peasants were forced to subdivide their small holdings even further and to earn money by working on estates. This led to a series of agrarian strikes (see Peasant strikes in Galicia and Bukovyna), the largest of which occurred in July–August 1902 with the participation of some 200,000 peasants. To alleviate the condition of the peasantry, the Populist intelligentsia strove to develop a strong co-operative movement, credit unions, and insurance companies. But for many impoverished peasants, even these efforts were insufficient. Beginning in the 1880s, a mass emigration began, mainly to the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina; by 1914, some 380,000 Ukrainians had left Galicia.

In the period 1867–1914, Ukrainian cultural and, to some extent, political life in Galicia underwent a remarkable growth. After the Ems Ukase prohibited Ukrainian publications in Russian-ruled Ukraine in 1876, Galicia became the ‘Piedmont’ of the Ukrainian movement. Much emphasis was placed on education as the basis of national consciousness and as the means of fostering new leaders, and significant progress in this field was made, especially in the decade before the First World War. By 1914 there were 2,500 public Ukrainian-language primary schools, but only 16 gymnasiums (10 of them private) and 10 teachers' seminaries. At Lviv University, 10 chairs held lectures in Ukrainian; the Chair of Ukrainian History directed by Mykhailo Hrushevsky was particularly important.

The Austrian government's efforts in 1890–4 to bring about a Polish-Ukrainian compromise (the so-called New Era) because of the threat of war with Russia benefited the Poles more than the Ukrainians and did not gain popular support. It resulted, however, in a regrouping of Ukrainian political forces. The Ukrainian Radical party (URP) was founded in 1890. The champion of agrarian socialism and anticlericalism, it opposed the policy of the New Era and the Populists who supported it. In 1895, influenced by Yuliian Bachynsky's Ukraïna Irredenta, the URP adopted the principle of Ukrainian independence. In 1899, the majority of the Populists and certain Radicals founded the National Democratic party (NDP). Advocating pan-Ukrainian independence as the final goal, this coalition party promoted democratic nationalism, social reform, and autonomy of the Ukrainian lands within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Also in 1899, the socialist faction of the URP broke away and founded the Ukrainian Social Democratic party (USDP). It pursued the goal of organizing Ukrainian workers in trade unions. In elections to the central parliament and the Galician diet, the NDP usually got about 60 percent of the Ukrainian popular vote, the URP, about 30 percent, and the USDP, about 8 percent.

In 1900, Andrei Sheptytsky became the new Greek Catholic metropolitan. Under his direction the Greek Catholic church became a staunch supporter of the Ukrainian national cause, and the priests played a much more active role in civic life. At the time, Ukrainian organized life flourished because of the efforts of the Prosvita society, the sports and youth organizations Sich society and Sokil, and the various economic and co-operative associations. Ukrainian-Polish differences were manifested by Ukrainian obstructionism in the Galician Diet, election campaign violence, Polish support of the Russophiles, Polish opposition to electoral reform, open hostility of the Poles to the creation of a separate Ukrainian university in Lviv, and student demonstrations and violence. Ethnic relations deteriorated to the extent that in 1908 the anti-Ukrainian Galician vicegerent Andrzej Potocki was assassinated by the student Myroslav Sichynsky. In this period international tensions came to play an important role in Galicia's domestic affairs. Worried about the impact of the Ukrainian national movement in Galicia on the population of its Ukrainian gubernias, the tsarist regime channeled much more funds to the movement's opponents in Galicia, the Russophiles, who disseminated pro-Russian propaganda in their press. The threat of a European war had existed since 1908, and on 7 December 1912, 200 leading members of the National Democratic party, Ukrainian Radical party, and Ukrainian Social Democratic party met in Lviv to discuss the international crisis caused by the Balkan War. They issued a declaration reaffirming the loyalty of Galicia's Ukrainians to Austria (this loyalty was suspected by the authorities because of the Russophiles' activity) and stating that in the event of war the Ukrainians would actively support Austria against Russia, the greatest enemy of the Ukrainian people.

When the First World War broke out, the Ukrainian parties founded the Supreme Ukrainian Council in August 1914 in Lviv. Headed by Kost Levytsky, the leader of the National Democratic party, it called for struggle against Russia as a means of liberating Ukraine and sponsored the creation of a legion of volunteers, the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, within the Austrian army. In autumn 1914, Russian forces occupied most of Galicia. Ukrainian organizations and the Ukrainian language were outlawed, and thousands of prominent Ukrainians, including Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, were arrested and deported to the east. During the Austrian retreat tens of thousands of Ukrainians suspected, rightly or wrongly, of sympathizing with Russia or being Russian agents were summarily executed; thousands were deported to internment camps, of which Thalerhof near Graz was the largest.

The Russian occupational administration under G. Bobrinsky pursued a policy of Russification with the co-operation of local Russophiles. Ukrainian leaders who had avoided deportation fled westward, mostly to Vienna. There, in May 1915, the General Ukrainian Council (GUC) was founded as the highest political representation of Ukrainians in the Austrian Empire. It consisted not only of 24 Galician and 7 Bukovynian representatives, but also of 3 members of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine, an organization of political émigrés from Russian-ruled Ukraine. In spring 1915, Austrian armies reoccupied most of Galicia, except for a strip of land between the Seret River and the Zbruch River. The GUC strove to obtain territorial autonomy for the Ukrainians of Galicia, but the Austrian regime sided with the Polish conservatives who proposed a Polish state consisting of Congress Poland and Galicia linked with the Habsburg monarchy by ties similar to those between Austria and Hungary. The Ukrainian parliamentary deputies in Vienna, headed by Yevhen Petrushevych, spoke out against the Polish proposal, demanding a separate Galician Ukrainian province and the guarantee of national autonomy well before the end of the war. The establishment of an autonomous Ukrainian government in Central Ukraine in 1917—the Central Rada in Kyiv—encouraged the Galician Ukrainian deputies to demand autonomy and, in late 1918, independence and the union of Galicia with the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR). Galician autonomy was demanded by the Ukrainian delegation during negotiations of the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers and was the subject of a secret additional agreement between the UNR and the Austro-Hungarian government signed on 9 February 1918.

The period of Western Ukrainian statehood. Before the collapse of the Habsburg state, Galician and Bukovynian political leaders—the members of parliament and the provincial diets and party delegates—gathered in Lviv on 18 October 1918 and created a constituent assembly, the Ukrainian National Rada. Headed by Yevhen Petrushevych, it proclaimed a Ukrainian state on the territories of Galicia, northern Bukovyna, and Ukrainian Transcarpathia. On 1 November (see November Uprising in Lviv, 1918), the Ukrainian National Rada seized the government buildings in Lviv and in the county towns of Galicia, thus bringing to an end nearly 150 years of Austrian rule. On 9 November, the Ukrainian National Rada defined the structure of the new Western Ukrainian National Republic (ZUNR) and elected its executive body—the State Secretariat of the Western Ukrainian National Republic headed by Kost Levytsky. From the start, the ZUNR encountered stubborn opposition from the Poles, and heavy fighting ensued. On 21 November, the Ukrainian National Rada was forced to quit Lviv and move to Ternopil and, in late December, to Stanyslaviv. The ZUNR began negotiating unification with the Ukrainian National Republic, and on 3 January 1919 the Rada ratified the law on unification. The union of the two states was officially proclaimed in Kyiv on 22 January 1919 and confirmed by the All-Ukrainian Labor Congress there.

National unification did not change the situation in Galicia where the administration remained in local Ukrainian hands (see Dictatorship of the Western Province of the Ukrainian National Republic), and the Ukrainian Galician Army (UHA) continued fighting the advancing Polish army, reinforced by the divisions of Gen Józef Haller. The Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia, 1918–19, lasted until July 1919, when the Ukrainian government and the UHA were forced to retreat east across the Zbruch River. The UHA fought alongside the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic against the Red Army (see Ukrainian-Soviet War, 1917–21). The ZUNR government under Yevhen Petrushevych went into exile in late 1919 and continued a diplomatic struggle from Vienna and Paris for the independence of Galicia and its recognition by the Entente Powers. During the Red Army's offensive against Poland in Galicia, the Galician Socialist Soviet Republic existed from July to September 1920 and was headed by a Moscow-backed provisional government—the Galician Revolutionary Committee led by Volodymyr Zatonsky. Poland emerged victorious in the Polish-Soviet War, and its occupation of Galicia and western Volhynia was recognized in the Peace Treaty of Riga in March 1921. In March 1923 the Conference of Ambassadors accepted that Ukrainian Galicia was part of Poland but with the proviso that Galicia would retain a certain degree of autonomy. This proviso was never honored by the interwar Polish government.

Galicia within interwar Poland, 1919–39. Well before the final international recognition of Galicia as part of Poland, Galicia was being administered as an integral part of Poland. In 1920 the Galician diet was formally abolished. Galicia was divided among the voivodeships of Cracow, Lviv, Stanyslaviv, and Ternopil; the latter three constituted ‘Eastern Little Poland’, and its Ukrainian inhabitants were officially referred to as Ruthenians (Rusini). The Ukrainians were subjected to a regime of terror—mass arrests, imprisonment in concentration camps, deportation, and the outlawing of Ukrainian organizations and periodicals. Ukrainians' access to government employment was denied. The region was left in a state of economic stagnation (made worse by wartime destruction), and the plight of the landless peasants was exacerbated by the officially promoted colonization of Galicia by ethnic Polish peasants.

The Ukrainians reacted by refusing to recognize the Polish regime. They boycotted the census of Galicia taken on 30 September 1921 and the 1922 elections to the Polish Sejm and Senate. The Ukrainian Labor party, Ukrainian Radical party, Ukrainian Social Democratic party, and Christian Social party joined forces in the Interparty Council (1919–23), which decided what lawful tactics to use against Polish policies and protested against the Polish occupation. Because Ukrainians were effectively excluded from Lviv University in the early 1920s and the university's Ukrainian chairs and lectureships were abolished, the Ukrainians organized various clandestine courses and then the Lviv (Underground) Ukrainian University (1921–5). Revolutionary nationalist struggle against the regime took the form of the underground Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO), led by Yevhen Konovalets, beginning in 1920.

In 1923, Ukrainian political tactics toward the regime began to change. Old parties were reconstituted, and new ones were formed. From 1925 the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance (UNDO) continued in the pragmatic tradition of the prewar National Democratic party and the Ukrainian Labor party (1919–25) to obtain certain advantages for the Ukrainians. It dominated several central cultural-educational and economic institutions—Prosvita, the Audit Union of Ukrainian Co-operatives, the Tsentrosoiuz union of farming and trade associations, and the Dnister Insurance Company—and controlled the influential daily Dilo. The Ukrainian Socialist Radical party replaced the Ukrainian Radical party in 1926. The Ukrainian Social Democratic party became pro-Soviet in 1923, was suppressed in 1924, and was revived in 1928 as a member of the Second International. Various parties of the Christian Social Movement remained active throughout the period. The Sovietophile Sel-Rob (Ukrainian Peasants' and Workers' Socialist Alliance) was founded in 1926, split into two factions in 1927, and was suppressed in 1932. Its majority supported the illegal, underground Communist Party of Western Ukraine, founded in 1919 as the Communist Party of Eastern Galicia, which advocated Galicia's unification with Soviet Ukraine. After the party split in 1927 into a national-Communist majority (which was expelled from the Communist International in 1928) and a Stalinist minority, it lost much of its support. The underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) replaced the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO) in 1929. Its leader remained Yevhen Konovalets, and its main base of support, as well as its main area of activity, was in Galicia. The Polish government responded to the revolutionary sabotage of the UVO-OUN and Ukrainian opposition to the regime with the military and police Pacification of Galicia in the fall of 1930—the destruction of Ukrainian institutional property, brutalization of Ukrainian leaders and activists, and mass arrests. This did not deter the OUN, which intensified its anti-Polish activity and assassinated the Polish minister of internal affairs, Bronisław Pieracki, in 1934, giving the regime the pretext to establish the Bereza Kartuzka concentration camp and to arrest and convict various OUN leaders, including Stepan Bandera and Mykola Lebed.

The legal activity of the Ukrainian parties in Galicia in the Polish Sejm and Senate from 1928 did not produce significant results. The Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance's efforts at reaching a Polish-Ukrainian compromise in the 1930s—the so-called Normalization—were inconclusive, because of the chauvinistic attitude of the Polish authorities and society at large and the increasingly authoritarian and repressive policies of the military rule under Józef Piłsudski.

Ukrainian culture and education suffered under interwar Polish rule. In 1921 education in Poland was centralized, and in 1924 Ukrainian and Polish schools were unified and made bilingual. By the 1930s many of these schools were Polish. To counterbalance the Polonization of education, Ukrainians began opening private schools with the help of the Ridna Shkola society. In the latter half of the 1930s, nearly 60 percent of all Ukrainian gymnasiums, teachers' seminaries, and vocational schools, with about 40 percent of all Ukrainian students, were privately run. Between the world wars, the co-operative movement became better organized and helped the Ukrainian farmers and farm workers—the majority of the Ukrainian population—to withstand economic instability and the Great Depression. The leading co-operative institutions were the Audit Union of Ukrainian Co-operatives, the Tsentrosoiuz union, the Maslosoiuz Provincial Dairy Union, the Silskyi Hospodar farmers' association, and the Union of Ukrainian Merchants and Entrepreneurs. They and other groups, such as the rapidly expanding women's movement and its organization, Union of Ukrainian Women, also contributed a great deal to the cultural development of Galicia's Ukrainians.

As in the Austrian era, the Ukrainians continued to maintain their own scholarly life, literature, press, and book publishing. The leading scholarly institutions were the Shevchenko Scientific Society and the Ukrainian Theological Scholarly Society, both of which published books and serials. Important scholarly, political, and cultural works were also published in the Basilian Fathers' Analecta Ordinis S. Basilii Magni/Zapysky ChSVV and in the leading Galician journal, Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk, which in 1932 was replaced by the journal Vistnyk, edited by the influential Dmytro Dontsov.

The Second World War. On the basis of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence on 23 August 1939, Galicia east of the Sian River was occupied by the Red Army between 17 and 23 September after Germany invaded Poland on 1 September. Soviet-style elections were held on 22 October to a People's Assembly of Western Ukraine, which in turn ‘requested’ the incorporation of the region into Soviet Ukraine. This request was ratified by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 1 November. A Soviet administration was immediately set up in Galicia. The new regime introduced fundamental changes—collectivization of agriculture, the nationalization of industry, the reorganization of the educational system on the Soviet model, albeit with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, the abolition of all existing Ukrainian institutions and periodicals, and the curtailment of the churches' activities. On 4 December Galicia was divided into four oblasts: Lviv oblast, Drohobych oblast, Stanyslaviv oblast, and Ternopil oblast. Many Ukrainian political and cultural leaders managed to flee west across the Sian River and the Buh River into the German-held Generalgouvernement of Poland, but many others did not. Thousands were arrested and deported to the east or died in prisons.

Germany broke the non-aggression pact and invaded the USSR on 22 June 1941. The German army took Lviv on 30 June 1941 and overran all of Galicia in July. Before they retreated, the Soviets executed some 10,000 Ukrainians who had been imprisoned in Galicia.

On 30 June 1941 in Lviv, the OUN (Bandera faction), which had organized the Legion of Ukrainian Nationalists to fight with the Germans against the Bolsheviks, proclaimed the re-establishment of the Ukrainian state in Western Ukraine and formed the Ukrainian State Administration under Yaroslav Stetsko (see Proclamation of Ukrainian statehood, 1941). This government was suppressed by the Germans on 12 July, and its members and leading members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists were arrested.

On 1 August, Galicia became the fifth district of the Generalgouvernement. The German annexation was protested by the Ukrainian National Council in Lviv, 1941(UNC), a public body representing Galicia's Ukrainians that was founded on 30 July and headed by Kost Levytsky (the honorary president was Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky). The UNC in Lviv was suppressed in March 1942 after Metropolitan Sheptytsky sent a letter to Heinrich Himmler protesting against the Germans' persecution of the Jews. The Ukrainian Regional Committee, founded in September 1941, remained the only legal civic umbrella institution; its general secretary was Kost K. Pankivsky. In March 1942, the functions of the committee were taken over by the Ukrainian Central Committee (UCC) based in Cracow, which had represented Ukrainians in the Generalgouvernement since 1940; Volodymyr Kubijovyč was its president, and Pankivsky became the vice-president. Ukrainian civic, cultural, and educational institutions were allowed by the German authorities (Governor-General Hans Frank and Governor Otto von Wächter) within the framework of the UCC. Besides organizing the Ukrainians economically and culturally and overseeing relief work, the UCC was instrumental in the creation of the volunteer Division Galizien in April 1943.

Compared to other Ukrainian territories under Nazi rule, Galicia was relatively better off. Nonetheless, the regime there was very severe: acts aimed at gaining political independence were forbidden; all opposition was brutally suppressed; and the vast majority of Galicia's Jews and Gypsies, as well as many Ukrainians, were murdered or sent to Nazi concentration camps (see Nazi war crimes in Ukraine). From June 1943, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) engaged in guerrilla warfare from its bases in the Carpathian Mountains against both the Germans and Sydir Kovpak's Soviet partisans (see Soviet partisans in Ukraine, 1941–5). As the Germans began retreating from Galicia, leaving Ternopil in April 1944, Lviv and Stanyslaviv in July, and Drohobych in August, the UPA and its political leadership, the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council, continued their struggle against the advancing Red Army.

The Soviet period. When the USSR reoccupied all of Galicia in the fall of 1944, the prewar Soviet regime was reinstalled. The mass persecution of Ukrainians who had co-operated with the German regime or had fought for Ukrainian sovereignty (ie, members of the OUN and soldiers of the UPA and the Division Galizien) ensued. Many Ukrainians were executed, and many others were sentenced to maximum terms in labor camps or deported to Soviet Asia. The official attitude towards the Ukrainian Catholic church was one of extreme hostility. Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky died on 1 November 1944. The hierarchs of the church, including the new metropolitan, Yosyf Slipy, were arrested on 11 April 1945 and sentenced to long terms in labor camps, where most of them died. The Soviet-staged Sobor of the Greek Catholic Church in 1946 held in Lviv renounced the Church Union of Berestia and decreed the abolition of the Ukrainian Catholic church and its ‘reunification’ with the Russian Orthodox church. Priests who refused to submit to these changes were imprisoned and/or deported. Well before the Soviet takeover, a large number of the Galician Ukrainian intelligentsia had fled westward. When the Second World War ended, they became displaced persons in Germany.

According to a Soviet-Polish agreement made in Moscow on 16 August 1945, the border between Polish- and Soviet-occupied Galicia ran along the Curzon Line; thus the Sian region (including Peremyshl), the Kholm region and the Lemko region were ceded to Poland. Soon after, Poles living on Soviet territory were resettled in Poland, and most of the Ukrainians living in the above regions were forcibly resettled in the Soviet Ukraine or in the regions newly acquired by Poland from Germany (see Operation Wisła). In 1951 the border between Poland and Lviv oblast was slightly modified. The forcible depopulation of Ukrainians in the border regions was calculated to destroy the social base of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which continued its activity in the Carpathian Mountains until the mid-1950s.

Because of the profound political, administrative, cultural, religious, social, economic, and demographic changes that have occurred under Soviet rule, historical Galicia has ceased to exist. The name is no longer used officially; instead, ‘Western Ukraine’ is now used to designate the territory of former Galicia (Lviv oblast, Ternopil oblast, and Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) together with western Volhynia (Volhynia oblast and Rivne oblast), northern Bukovyna (Chernivtsi oblast), and Transcarpathia (Transcarpathia oblast).

Population. Galicia has long been the most densely populated part of Ukraine. Although in 1939 it constituted only 6 percent of all Ukrainian ethnic territory, it had 10.5 percent of the latter's total population and almost 10 percent of all Ukrainians. Galicia was already densely populated during the Princely era. Most densely populated were the vicinities of Peremyshl, Lviv, and Halych. From the 13th to the 16th century, the population increased because of the influx of Ukrainians from the east and Polish colonists from the west. From the 15th to the 18th century Galicia also experienced population losses, caused primarily by the peasantry's flight from serfdom to the steppe frontier. After the Austrian annexation, this large-scale flight was stemmed because the Russian-Austrian border now separated Galicia from the rest of Ukraine, and the population rose steadily. It increased by 45 percent between 1869 and 1910. This growth was interrupted only by mass emigration, beginning in the 1890s. In 1939, the average population density in Galicia was 104 per sq km; in the belt between Peremyshl and Pokutia it was as high as 150 per sq km. The urban population grew slowly, from 19 percent in 1900 to 23 percent in 1931; the greatest growth occurred in Lviv and in the towns of the Drohobych-Boryslav Industrial Region. The cities with over 20,000 inhabitants in 1931 (their 2014 population is given in parentheses) were Lviv, 316,000 (729,038); Stanyslaviv (Ivano-Frankivsk), 60,000 (227,030); Peremyshl 51,000 (64,276 in 2012); Boryslav, 42,000 (35,040 in 2011); Ternopil, 36,000 (217,110); Kolomyia, 33,000 (61,429 in 2012); Drohobych, 33,000 (77,624 in 2011); Stryi, 31,000 (60,112 in 2012); and Sambir, 22,000 (35,002 in 2012).

Until the Second World War, Galicia was one of the most overpopulated agrarian regions in Europe, with 101 agriculturalists per 100 ha of arable land (the corresponding figure for all of Ukraine was 54, for Germany, 51, and for Holland, 70). In the last 150 years, certain demographic trends can be singled out: (a) until 1890, a small annual growth (around 1.1 percent) and a high mortality rate; (b) from 1890 to 1914, an average annual natural increase of 14–15 per 1,000 inhabitants (in 1911–13, the birth rate was 40.3 and the mortality rate was 25.9 per 1,000), mass emigration overseas (a total of 380,000 persons), a high rate of seasonal migration for work (up to 100,000 annually), and an influx of Poles into the towns and the countryside; (c) from 1914 to 1921, a population decline of 12 percent; (d) from 1920 to 1939, a sharp decline in natural growth (eg, in 1938 there were 23.9 births and 15.6 deaths per 1,000 inhabitants) and a decrease in emigration (a total of 120,000) and in the influx of Poles; (e) from 1939 to 1945, continued decline in natural growth, the almost total extermination of the Jewish population, the resettlement of the Ukrainian and Polish populations on either side of the new, postwar Soviet-Polish border, the emigration of over 100,000 Ukrainians to the West, and the deportation of an unknown but large number of Ukrainians to the Soviet east; and (f) in the postwar period, a nearly normal rate of natural increase, migration of part of the population to other regions of the USSR (particularly to the Donets Basin and the virgin lands of Central Asia), intensive urbanization, and a large influx of Russians.

Because of centuries-long Polish expansion there, Galicia was the first region of Ukraine to cease being purely Ukrainian; this process transpired first in the towns and later in the most fertile areas of the countryside. The percentage of Poles and/or Roman Catholics increased because their in-migration occurred at the same time as the mass emigration of Ukrainians. In the period 1880–1939 the number of Roman Catholics rose from 19.9 to 25 percent, while the number of Greek Catholics and Jews fell from 66.8 to 64.4 percent and 12.3 to 9.8 percent respectively. An intermediate ethnic category arose, the so-called latynnyky (Ukrainian-speaking Roman Catholics), ie, either Ukrainians who had converted to Roman Catholicism or the descendants of Polish colonists who had to a large degree assimilated into the Ukrainian milieu. A smaller transitional category consisted of Ukrainian Catholics living in a Polish milieu who had become linguistically Polonized (mainly in the western borderlands and in Lviv).

It has been estimated by Volodymyr Kubijovyč (1983) that on 1 January 1939 Galicia had a population of 5,824,100, consisting (percentages are given in parentheses) of 3,727,600 Ukrainians (64.1); 16,400 Polish-speaking Ukrainian Greek Catholics (0.3); 947,500 Poles (16.2), of whom 72,300 (1.2) arrived in the years 1920–39; 515,100 latynnyky (8.8); 569,300 Jews (9.8); and 49,000 Germans and other ethnic minorities (0.8).

Economy. In the Princely era, the economic base of Galicia changed gradually from hunting and utilization of forest resources to agriculture. At the time, grain, as well as hides and wax, was already being exported to Byzantium. Trade in salt mined in Subcarpathia was of particular economic importance. It was exported west via the Sian River and east to Kyiv via land trade routes. From the 12th century, Galicia played the role of intermediary in the trade between the West and the Black Sea. In the 15th and 16th centuries, an economy based on the filvarok developed; the nobility exploited the peasantry in order to export as much grain, beef, wax, and timber products as possible to the rest of Europe. At the same time the salt industry grew, and other industries, such as liquor distilling, brewing, and arms manufacturing (in Lviv), arose. In the 16th century, trade with lands to the east became more difficult; the cities and towns declined because of the detrimental policies of the Polish nobility. Incessant wars and the oppression of the Ukrainian burghers and peasantry resulted in the impoverishment of the population. When Austria annexed Galicia in 1772, it was a poor, backward, and overpopulated land.

Under Austria, Galicia's depressed economy only minimally improved. Its recovery was hindered by a thoroughly unhealthy agrarian system (which did not change even after the abolition of serfdom) and by Austrian economic policies that maintained Galicia as a primarily agricultural internal colony from which the western Austrian provinces could draw cheap farm produce and timber and which they could use as a ready market for their manufactured goods (particularly textiles). Small industrial enterprises (most of them in the hands of landowners), such as textile factories, foundries, glass works, salt mines, paper mills, and sugar refineries, that had been productive in the first half of the 19th century declined thereafter because they were unable to compete with the industries of the western provinces and could not modernize because of a lack of capital, the absence of indigenous coal and iron ore, the long distance from Austria's industrial centers, and poor commercial and communication links with the rest of Ukraine. Only the food industry (liquor distilling and milling by small enterprises) and, beginning in the 1850s, the petroleum industry were developed in Galicia, and only the latter attracted foreign investment. Intensive agriculture could not develop because the peasants had little land, which was further parceled among the family members, and no capital, while the large landowners preferred to maintain the status quo and showed no initiative. Only emigration saved the peasants from destitution; with the exception of Transcarpathia, this process was more significant in Galicia than anywhere else in Ukraine.

Under interwar Poland, Galicia's economic state became even worse. Rural overpopulation increased because of a decline in emigration and the mass influx of Polish colonists, and industry deteriorated even further. The situation of the Ukrainian population became even more precarious with its exclusion from jobs in the civil service and in Polish-owned enterprises. Only through self-organization, especially through the co-operative movement, were the Ukrainians able to avoid economic ruin.

The postwar Soviet annexation placed Galicia's economy on a par with that of the rest of Ukraine. Agriculture was collectivized, and intensive cultivation of industrial crops, mainly sugar beets and corn, was introduced. Great changes occurred in the industrial sector by way of the large-scale exploitation of energy resources and the introduction of new industries.

In general Galicia's economy had been neglected for centuries, and its economic potential—based on its generally good farmland and propitious climate (milder and more humid than in other parts of Ukraine), sources of energy (rivers, petroleum, natural gas, timber, peat, lignite, and anthracite), and abundant labor supply—has been underdeveloped. As late as 1931, for example, 74.6 percent of the population (88 percent of the Ukrainians) were still engaged in agriculture, while only 10.9 percent (5.8 percent) were engaged in industry, 4.7 percent (1.7 percent) in trade and transport, and 9.8 percent (4.4 percent) in other professions. Arable land and farmsteads took up 52 percent of the territory; pastures, grassland, and meadows, 18 percent; forest, 25 percent; and other land, 5 percent. In the Carpathian Mountains forest took up 43 percent; pastures and meadows, 35 percent; and arable land, only 16 percent. In eastern Galician Podilia and Pokutia, arable land took up 77 percent. In Roztochia, western Galician Podilia, and Subcarpathia, arable land took up 50 percent (25 percent was forest and 20 percent was meadows and pastures).

Before the Second World War, Galicia had a sown area of 2,540,000 ha, of which 470,000 ha (18.5 percent) were devoted to wheat, 520,000 ha (20.5 percent) to rye, 220,000 ha (8.7 percent) to barley, 390,000 ha (15.4 percent) to oats, 80,000 ha (3.2 percent) to corn, 60,000 ha (2.4 percent) to buckwheat, 20,000 ha (0.8 percent) to millet, 440,000 ha (17.3 percent) to potatoes, 260,000 ha (10.2 percent) to fodder crops, and 50,000 ha (2.0 percent) to industrial crops (of which sugar beets took up 11,000 ha; flax, 13,000 ha; hemp, 15,000 ha; and rape, 5,000 ha). After the war, the area sown with industrial crops (especially with sugar beets and corn) was increased. In the Carpathian Mountains, oats and potatoes predominated; corn predominated in Pokutia and southeast Podilia; and more wheat than rye was grown in Pokutia, eastern Podilia, and Sokal county.

The poverty of the peasantry is reflected by their holdings in the 1930s. Landowning peasants together possessed only 55 percent of the land, including forests and pastures (80 percent of the arable land); 52 percent of the peasants had less than 2 ha each, 37 percent had from 2 to 5 ha, and only 11 percent had more than 5 ha. Landlessness was rampant and constantly increasing. Consequently, intensive crop growing was not possible, and harvest yields were very low, on the average 5,000 kg of grain and 5,500 kg of potatoes per ha. Even though the population had barely enough food for its own use (before the war, an annual per capita average of 90 kg of wheat and rye, 70 kg of other grain, and 395 kg of potatoes), 200,000 t of wheat and barley were annually exported from Galicia, and only a small amount of rye flour was imported. Animal husbandry was practiced more intensively and constituted the basis of the peasant budget. In 1936, for example (figures in parentheses are per 100 ha of arable land and per 100 inhabitants), 649,000 (17, 11) horses, 1,602,000 (42, 28) head of cattle, of which 1,116,000 were cows, 648,000 (17, 11) pigs, and 387,000 (10, 7) goats and sheep were raised. In general the livestock density in relation to the farmland area in Galicia was greater than elsewhere in Ukraine, and the population's livestock supply was adequate. Horticulture, orcharding (including viticulture in southeast Podilia), and beekeeping played a secondary role.

Industry in Galicia before 1945 was less developed than elsewhere in Ukraine. Manufacturing was based on the processing of indigenous raw materials, including agricultural products, timber, petroleum, and potassium salts; there was practically no textile industry or metallurgy. Therefore the prewar industrial work force was small (with a maximum of 44,000 in 1938), only 2.2 percent of Galicia's hydroelectric capacity was exploited, and electrification proceeded very slowly. Low-grade lignite was mined around Kolomyia, Rava-Ruska, Zhovkva, and Zolochiv, but not on a large scale because of competition from Silesia's coal companies (see Subcarpathian Lignite Region). Petroleum extraction near Boryslav, Bytkiv, Nadvirna, and elsewhere in the Subcarpathian Petroleum and Natural Gas Region was 2,100,000 t (5 percent of world production) in 1909; it fell to 717,000 t in 1938. The natural-gas industry arose in 1923 and was centered in Dashava, which supplied gas to towns in Subcarpathia; in 1938 215 million cu m of gas were extracted. Salt mines near Drohobych, Dobromyl, Bolekhiv, and Dolyna produced in the prewar years a mere 40,000 t, or 2 percent of Ukraine's salt. Ozocerite was mined near Boryslav, Truskavets, Starunia, and Dzvyniach; its production fell from 12,300 t in 1885 to 600 t in 1938. The mining of potassium salt near Stebnyk and Kalush increased, reaching 567,000 t in 1938. The lumber industry in Subcarpathia was well developed; two-thirds of its products were exported. The food industry was underdeveloped; it produced primarily flour, beer, liquor, meat and dairy products, and beet sugar (only three sugar refineries existed before the war). The building-materials industry produced, on a limited scale, glass (in Lviv and Stryi), plaster of paris and lime (in the Dnister River Basin), bricks, and tiles. Light industry was not developed enough to supply the population's needs; small companies manufactured leather, wadding, quilts, curtains, shoes, and clothing accessories. Machine building was not well developed; it was based in Lviv and Sianik.

Before the Soviet period artisans and the cottage industry played an important role in Galicia, especially in the Hutsul region. Health resorts and sanatoriums, mineral waters, and spas, most of them in the Carpathian Mountains, attracted thousands of visitors. The network of railroads and highways was denser than elsewhere in Ukraine, but most roads were in a state of disrepair. Rivers were used merely to float timber to sawmills. (For the economy of postwar Galicia, see Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, Lviv oblast, and Ternopil oblast.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Zubritskii, D. Kritiko-istoricheskaia povest' vremennykh let Chervonoi, ili Galitskoi Rusi (Moscow 1845)

Sharanevych, Y. Ystoriia Halytsko-Volodymyrskoy Rusy ot naidavniishykh vremen do roku 1453 (Lviv 1863)

Levytskyi, I. Halytsko-ruskaia bybliohrafiia XIX-ho stolitiia s uvzhliadneniiem ruskykh izdanii poiavyvshykhsia v Uhorshchyni i Bukovyni (1801–1886), 2 vols (Lviv 1888, 1895)

Zanevych, I. [Terlets’kyi, O.]. Znesenie panshchyny v Halychyni: Prychynok do istoriï suspil'noho zhytia i suspil'nykh pohliadiv 1830–1848 rr. (Lviv 1895)

Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, 12: Galizien (Vienna 1898)

Franko, Ivan. (ed). Materiialy do kul’turnoï istoriï Halyts’koï Rusy XVIII i XIX viku (Lviv 1902)

Mises, L. von. Die Entwicklung des gutsherrlich-bäuerlichen Verhältnisses in Galizien (1772–1848) (Vienna 1902)

Bujak, F. Galicya, 2 vols (Lviv 1908–9)

Krevets'kyi, I. ‘Halychyna v druhii polovyni XVIII v.’, ZNTSh, 91 (Lviv 1909)

Baran, S. Statystyka seredn'oho shkil'nytstva u Skhidnii Halychyni v rr. 1848–1898 (Lviv 1910)

Franko, Ivan. Panshchyna i ïï skasuvannia v 1848 r. v Halychyni (Lviv 1913)

Bujak, F. Rozwój gospodarczy Galicyi (1772–1914) (Lviv 1917)

Doroshenko, D. ‘Rosiis'ka okupatsiia Halychyny 1914–1916 rr.’, Nashe mynule, 1 (Kyiv 1918)

Doroshenko, V. ‘Zakhidn'o-ukraïns'ka Narodna Respublika’, LNV, 1919, nos 1–3

Studyns'kyi, K. (ed). ‘Materiialy dlia istoriï kul'turnoho zhyttia v Halychyni v 1795–1857 rr.’, URA, 13–14 (Lviv 1920)

Lozyns'kyi, M. Halychyna v rr. 1918–1920 (Vienna 1922, New York 1970)

Vozniak, M. Iak probudylosia ukraïns'ke narodnie zhyttia v Halychyni za Avstriï (Lviv 1924)

Levyts'kyi, K. Istoriia politychnoï dumky halyts'kykh ukraïntsiv 1848–1914, 2 vols (Lviv 1926–7)

Shymonovych, I. Halychyna: Ekonomichno-statystychna rozvidka (Kyiv 1928)

Levyts'kyi, K. Istoriia vyzvol'nykh zmahan' halyts'kykh ukraïntsiv z chasu svitovoï viiny, 3 vols (Lviv 1929–30)

Kuz'ma, O. Lystopadovi dni 1918 r. (Lviv 1931, New York 1960)

Pasternak, Iaroslav. Korotka arkheolohiia zakhidno-ukraïns'kykh zemel' (Lviv 1932)

Andrusiak, M. Geneza i kharakter halyts'koho rusofil'stva v XIX–XX st. (Prague 1941)

Barvins'kyi, B. Korotka istoriia Halychyny (Lviv 1941)

Baran, S. Zemel'ni spravy v Halychyni (Augsburg 1948)

Matsiak, V. Halyts'ko-Volyns’ka derzhava 1290–1340 rr. u novykh doslidakh (Augsburg 1948)

Pashuto, V. Ocherki po istorii Galitsko-Volynskoi Rusi (Moscow 1950)

Kieniewicz, S. (ed). Galicja w dobie autonomicznej (1850–1914): Wybór tekstów (Wrocław 1952)

Babii, B. Vozz'iednannia Zakhidnoï Ukraïny z Ukraïns'koiu RSR (Kyiv 1954)

Materialy i doslidzhennia z arkheolohiï Prykarpattia i Volyni, 1–5 (Kyiv 1954–64)

Tyrowicz, M. (ed). Galicja od pierwszego rozbioru do wiosny ludów 1772–1849: Wybór tekstów źródłowych (Cracow 1956)

Z istoriï Zakhidnoukraïns'kykh zemel', 1–8 (Kyiv 1957–63)

Najdus, W. Szkice z historii Galicji, 2 vols (Warsaw 1958–60)

Grzybowski, K. Galicja 1848–1914: Historia ustroju politycznego na tle historii ustroju Austrii (Cracow 1959)

Herbil’s’kyi, H. Peredova suspil'na dumka v Halychyni (30-i–seredyna 40-ykh rokiv XIX stolittia) (Lviv 1959)

Kravets', M. Narysy robitnychoho rukhu v Zakhidnii Ukraïni v 1921–1939 rr. (Kyiv 1959)

Kompaniiets', I. Stanovyshche i borot'ba trudiashchykh mas Halychyny, Bukovyny ta Zakarpattia na pochatku XX st. (1900–1919 roky) (Kyiv 1960)

Sokhotskyi, I. (ed). Istorychni postati Halychyny XIX–XX st. (New York–Paris–Sidney–Toronto 1961)

Steblii, F. Borot'ba selian skhidnoï Halychyny proty feodal'noho hnitu v pershii polovyni XIX st. (Kyiv 1961)

Rozdolski, R. Stosunki poddańcze w dawnej Galicji, 2 vols (Warsaw 1962)

Hornowa, E. Stosunki ekonomiczno-społeczne w miastach ziemi Halickiej w latach 1590–1648 (Opole 1963)

Herbil's'kyi, H. Rozvytok prohresyvnykh idei v Halychyni u pershii polovyni XIX st. (do 1848 r.) (Lviv 1964)

Kravets', M. Selianstvo Skhidnoï Halychyny i Pivnichnoï Bukovyny u druhii polovyni XIX st. (Lviv 1964)

Kosachevskaia, E. Vostochnaia Galitsiia nakanune i v period revoliutsii 1848 g. (Lviv 1965)

Sviezhyns'kyi, P. Ahrarni vidnosyny na Zakhidnii Ukraïni v kintsi XIX–na pochatku XX st. (Lviv 1966)

Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Martha. The Spring of a Nation: The Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia in 1848 (Philadelphia 1967)

Hornowa, E. Ukraiński obóz postępowy i jego współpraca z polską lewicą społeczną w Galicji 1876–1895 (Wrocław 1968)

Grodziski, S. Historia ustroju społeczno-politycznego Galicji 1772–1848 (Wrocław–Warsaw–Cracow–Gdańsk 1971)

Baran, V. Ranni slov'iany mizh Dnistrom i Pryp'iattiu (Kyiv 1972)

Hrabovets'kyi, V. Zakhidnoukraïns'ki zemli v period narodno-vyzvol'noï viiny 1648–1654 (Kyiv 1972)

Chernysh, O. (ed). Starodavnie naselennia Prykarpattia i Volyni (Doba pervisnoobshchynnoho ladu) (Kyiv 1974)

Serhiienko, H. (ed). Klasova borot'ba selianstva skhidnoï Halychyny (1772–1849): Dokumenty i materialy (Kyiv 1974)

Glassl, H. Das österreichische Einrichtungswerk in Galizien (1772–1790) (Wiesbaden 1975)

Horn, M. Osadnictwo miejskie na Rusi Czerwonej w latach 1501–1648 (Opole 1977)

Sirka, A. The Nationality Question in Austrian Education: The Case of Ukrainians in Galicia, 1867–1914 (Frankfurt am Main 1979)

Chernysh, O. et al (eds). Arkheolohichni pam'iatky Prykarpattia i Volyni kam'ianoho viku (Kyiv 1981)

Markovits, A.; Sysyn, Frank. (eds). Nationbuilding and the Politics of Nationalism: Essays on Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, Mass 1982)

Himka, J.-P. Socialism in Galicia: The Emergence of Polish Social Democracy and Ukrainian Radicalism (1860–1890) (Cambridge, Mass 1983)

Kubiiovych, V. Etnichni hrupy pivdennozakhidnoï Ukraïny (Halychyny) na 1.1.1939: Natsional'na statystyka i etnohrafichna karta (Wiesbaden 1983)

Magocsi, Paul. Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide (Toronto–Buffalo–London 1983)

Kozik, Jan. The Ukrainian National Movement in Galicia: 1815–1849 (Edmonton 1986)

Gross, J. Revolution From Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia (Princeton, New Jersey 1988)

Himka, John-Paul. Galician Villagers and the Ukrainian National Movement in the Nineteenth Century (Edmonton 1988)

Himka, John-Paul. Galicia and Bukovina: A Research Handbook About Western Ukraine, Late 19th–20th Centuries (Edmonton 1990)

Hryniuk, Stella. Peasants With Promise: Ukrainians in Southeastern Galicia 1880–1900 (Edmonton 1991)

Partacz, Cz. Od Badeniego do Potockiego: Stosunki Polsko-Ukraińskie w Galicji w latach 1888–1908 (Toruń 1996)

Zayarnyuk, Andriy. Framing the Ukrainian Peasantry in Habsburg Galicia, 1846–1914 (Toronto–Edmonton 2013)

Swiątek, Adam. Gente Rutheni, Natione Poloni: The Ruthenians of Polish Nationality in Habsburg Galicia (Toronto–Edmonton 2019)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Yaroslav Pasternak, Illia Vytanovych, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article was updated in 2014.]