Futurism

Futurism. Art movement that originated in Italy in 1909. Its founder is considered to be F. Marinetti, whose main objective was to destroy old art forms, particularly realism and classicism, the dominant trends of the 19th century. Cubism still recognized a certain convention, while futurism rejected all accepted forms and gave individualism free reign. In painting this freedom led to fantastic forms and colors, and in literature, especially poetry, to abstruse language (zaumna mova) consisting of sound-words that often had no meaning. Futurism sought to transmit the ideas and spirit of the future technological and cosmopolitan society, which was opposed to the old conservative esthetic sensibility of the peasants and petite bourgeoisie. Hence, urban and industrial themes were typical of this movement. One of the key devices of the futurists was the ‘shocking of the bourgeois,’ that is, provoking him/her with various inventions and deformations. Futurism did not receive much sympathy in Ukraine before the First World War because of the dominance of the tradition-oriented peasant masses. Such works as Alexander Archipenko's Dance or Medrano I (1912) were produced in Paris and were known in Ukraine only from reproductions.

The first collection of Ukrainian futurist poetry—Mykhailo Semenko's Preliud (Prelude)—appeared in 1913. It was followed by Derzannia (Audacity) and Kverofuturyzm (Querofuturism). As an active proponent of futurism, Semenko founded several Ukrainian futurist organizations and journals: Fliamingo (1919–21), ASPANFUT (Association of Panfuturists, 1921–4), and, after moving to Kharkiv from Kyiv, the journal Nova generatsiia (1927–30). Because only Communist ideals were permitted, the journal became a militant advocate of ‘proletarian art.’ At first it called for the destruction of old forms and, when this was recognized to be of little use for the building of a new society, it propagated constructivism and suprematism. After Kazimir Malevich's expulsion from Moscow, Semenko published a series of Malevich's articles on suprematism in his journal. A number of talented poets belonged to the futurist group: Geo Shkurupii and Oleksa Vlyzko, who like Semenko were executed for ‘nationalism’ in the 1930s, Mykola Skuba, and the theoretician Oleksii Poltoratsky. The eminent poet Mykola Bazhan and the greatest poet of the Ukrainian revolutionary period, Pavlo Tychyna, were for some time influenced by futurism and utilized some of its ideas in their work. The poet Valeriian Polishchuk was closely associated with futurism, on the basis of which he tried to build his own movement of ‘dynamic spiralism.’ The futurists were never as prominent in the Ukrainian literature of their time as the symbolists or Neoclassicists, who never severed their ties with the past. Yet the futurists succeeded in reinvigorating poetry by introducing fresh themes and forms and above all by their experimentation. The group Nova Generatsiia propagated new Western European trends such as Dadaism and surrealism, although this practice conflicted with its journal's official crude sociological declarations. The journal ceased publication under pressure from the authorities.

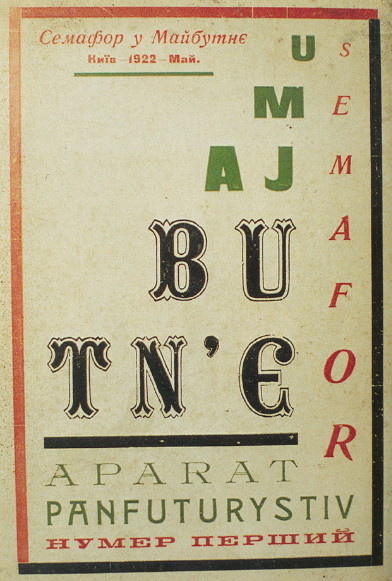

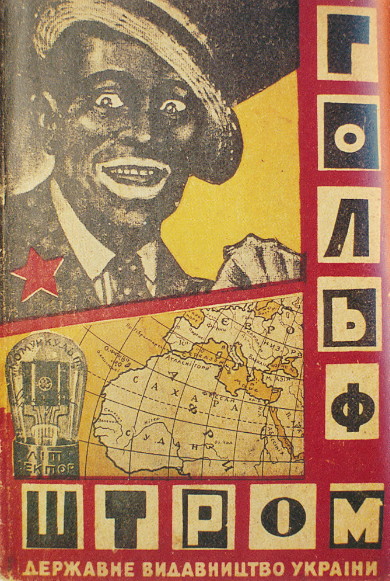

Besides the organizations mentioned above, there were also local groups of futurists: Kom-Kosmos in Kharkiv (1921), Yugolif (including local Russian futurists) in Odesa, and SiM (Selo i Misto [Village and City]) in Moscow (1925), which embraced Ukrainian writers in the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. All these groups rejected the classical legacy and advocated ‘the destruction of forms’ for the sake of ‘the Communist future.’ In the 1920s the futurists published the following periodicals: Universal’nyi zhurnal, Semafor u maibutnie, Katafalk iskusstva, and Holfshtrom.

In the fine arts, besides Alexander Archipenko, who left Ukraine in 1906, the following artists in Ukraine were closely associated with futurism of the constructivist rather than the anarchist bent (the so-called cubo-futurism): Alexandra Ekster, Oleksander Bohomazov, Anatol Petrytsky, Kazimir Malevich, Mykhailo Semenko's brother Vasyl, Vasyl Yermilov, Ye. Prybylska, Yevhen Sahaidachny, Osyp Sorokhtei, Pavlo Kovzhun, and the members of the Nova Generatsiia circle. Still, before all the literary and artistic organizations were disbanded in Ukraine in 1932, futurism was officially denounced as bourgeois and was banned.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Leites, A.; Iashek, M. Desiat’ rokiv ukraïns’koï literatury, 1 (Kharkiv 1928)

Hordyns’kyi, Ia. Literaturna krytyka pidsoviets’koï Ukraïny (Lviv–Warsaw 1939)

Luckyj, G. Literary Politics in the Soviet Ukraine, 1917–34 (New York 1956)

Ilnytzkyj, O. Ukrainian futurism, 1914-1930: a historical and critical study (Cambridge, Mass 1997)

Sviatoslav Hordynsky

[This article was originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)