Film

Film. Motion pictures were first seen in Ukraine in 1896 when the cinematographic productions of the Lumière brothers appeared in Odesa and then spread to other cities. At first short films that were imported from France were shown. These were soon joined by others when Alfred Fedetsky, a photographer in Kharkiv, began to show his own homemade films, such as Train Departing from the Kharkiv Station, Procession of the Cross from Kuriazh to Kharkiv (1896), and Folk Celebrations at the Horse Market (1897). At the beginning of the 20th century film studios in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa began to produce films on Ukrainian themes. Oleksa Oleksiienko, D. Baida-Sukhovii, and Danylo Sakhnenko were among the first Ukrainian film directors. At first primitive, everyday dramas were filmed, but by the early 1910s the classics of drama were being produced. In particular, the Katerynoslav studio filmed in 1911 the Sadovsky's Theater performing Ivan Tobilevych's Naimychka (The Servant Girl) and Ivan Kotliarevsky's Natalka Poltavka (Natalka from Poltava) featuring Mykola Sadovsky, Mariia Zankovetska, Hanna Borysohlibska, Liubov Linytska, and Ivan Marianenko. With the outbreak of the Revolution of 1917 the development of cinema almost ceased. Only the Ukrainfilm studio, which was established in 1918 during Ukrainian independence, produced a few documentary films.

Period of the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration. After occupying Ukraine, the Soviets nationalized all private film studios and placed them under the jurisdiction of the cinema section of the Theater Committee. After several reorganizations the section became in 1922 the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration (VUFKU) and was subordinated to the People's Commissariat of Education. Thus began the most productive period in the development of the Ukrainian cinema, which lasted to the beginning of the 1930s. During this period the production base of the film industry, the technical and artistic cadres, and the network of theaters expanded enormously. At first there were only two film studios (known as film factories)—one in Yalta and one in Odesa (see Odesa Artistic Film Studio). In 1929 the largest VUFKU film studio opened in Kyiv (see Kyiv Artistic Film Studio). Four films were produced in 1923, 16 in 1924, 20 in 1927, 36 in 1928, and 31 in 1929. In these years the technical-manufacturing personnel of the studios increased from 47 in 1923 to 1,000 in 1929. The number of movie theaters grew just as rapidly, from 265 in 1914 to 5,394 in 1928. The outstanding film directors of this period were Petr Chardynin, V. Hardin, Yurii Stabovy, Heorhii Tasin, Dziga Vertov, Marko Tereshchenko, Favst Lopatynsky, Oleksander Dovzhenko, and Ivan Kavaleridze. Among the large number of screenwriters there were some well-known Ukrainian writers—Mykola Bazhan, Yurii Yanovsky, Hryhorii Epik, Dmytro Falkivsky, Oles Dosvitnii, and Maik Yohansen. Besides the stars of Ukrainian theater who acted in films before the revolution, many prominent actors of the older and the younger generations appeared in films. Among them were Ivan Zamychkovsky, Yurii Shumsky, Stepan Shkurat, Mykola Nademsky, and the following actors of the Berezil theater: Amvrosii Buchma, Liubov Hakkebush, Marian Krushelnytsky, Valentyna Chystiakova, Nataliia Uzhvii, and Petro Masokha.

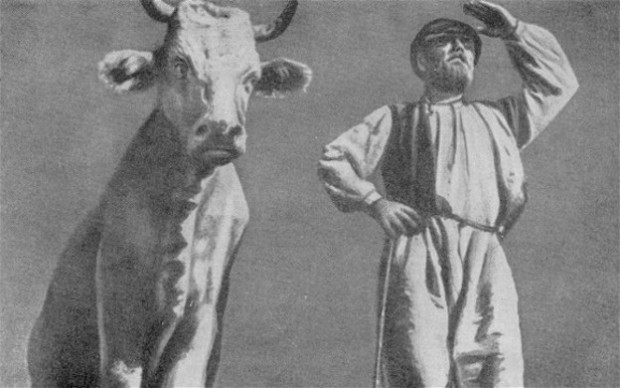

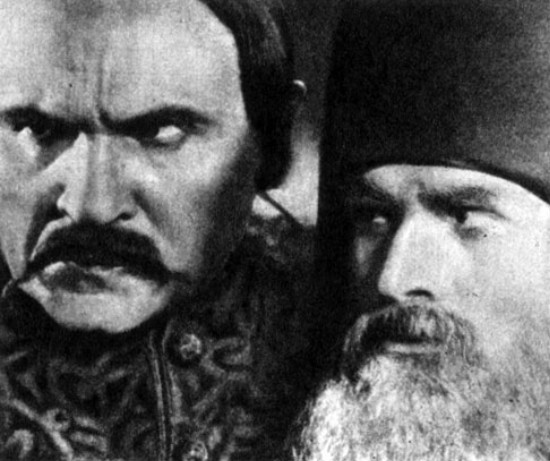

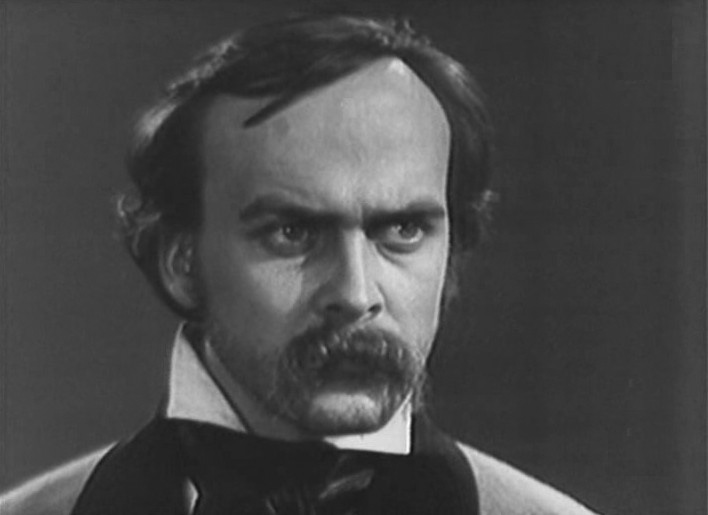

A number of excellent films on purely Ukrainian themes were made in this period: Taras Shevchenko (1926), directed by Petr Chardynin and starring Amvrosii Buchma in the title role; Boryslav smiiet’sia (Boryslav Is Laughing, 1927), based on Ivan Franko's novel, directed by I. Rona and starring Ivan Zamychkovsky and Yurii Shumsky; Mykola Dzheria (1927), based on Ivan Nechui-Levytsky's novel, directed by Marko Tereshchenko and starring A. Buchma in the main role; Taras Triasylo (1927), directed by P. Chardynin and starring A. Buchma, Nataliia Uzhvii, I. Zamychkovsky, and Yu. Shumsky; Cherevychky (The Shoes, 1928), based on a work by Nikolai Gogol and directed by P. Chardynin; Zvenyhora (1928), directed by Oleksander Dovzhenko and starring Semen Svashenko and Mykola Nademsky. All these films to some degree marked a technical and artistic achievement in the history of silent film. Many of them were attacked by the official critics for nationalist deviations and were banned in the early 1930s. Ivan Kavaleridze's film Zlyva (The Downpour, 1929), starring Stepan Shkurat and Ivan Marianenko, was criticized with particular severity. It attempted to present the epic of the Haidamaka uprisings and experimented with innovations in form, using a black velvet backdrop and geometric props instead of a naturalistic setting.

In this period a number of other films on Soviet themes still preserved a Ukrainian setting to a considerable degree and, in spite of official propaganda, managed to convey real life artistically. Among them were Ostap Bandura (1924), one of the first films about the civil war, directed by V. Hardin and starring Mariia Zankovetska; Ukraziia (1925), directed by Petr Chardynin; Dva dni (Two Days, 1927), directed by Yurii Stabovy; Arsenal (1929), written and directed by Oleksander Dovzhenko and starring Semen Svashenko and Amvrosii Buchma. Several films are known for the masterly performance of the actors, for example, Prodanyi apetyt (The Sold Appetite, 1928), starring A. Buchma and directed by N. Okhlopkov. Documentary films of the period such as Dziga Vertov's Odynadtsiatyi (The Eleventh One, 1928), Cholovik z kinoaparatom (Man with a Movie Camera, 1929), and Symfoniia Donbasu (Symphony of the Donbas, 1931) are interesting because of their formal innovations.

The best Ukrainian silent motion pictures were Oleksander Dovzhenko's three films, which won him the reputation as ‘the first poet of cinema’—Zvenyhora, Arsenal, and particularly Zemlia (The Earth, 1930). In 1958 an international jury included Zemlia among the 12 best films in world cinematography. Dovzhenko developed his own style in the art of motion pictures and trained a group of actors according to its demands. Among these actors Stepan Shkurat, Mykola Nademsky, Petro Masokha, and Semen Svashenko were particularly well known. A separate school of camera work in the Ukrainian cinema emerged under Dovzhenko. Its most outstanding representative was Danylo Demutsky.

1930–41. The end of silent films in the history of the Ukrainian cinema coincided with the beginning of the campaign to crush Ukrainian culture, including the cinema. The All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration, which until 1930 was independent, was then reorganized into Ukrainfilm and shortly thereafter subordinated to central Soviet film organizations in Moscow. The semimonthly magazine Kino (1925–33) ceased publication. The Odesa Artistic Film Studio was used almost exclusively by Mosfilm and Lenfilm, while the Yalta film studio was officially transferred to Russian film organizations. Film directors such as Yurii Stabovy and Favst Lopatynsky, cameramen such as Danylo Demutsky, and screen writers such as Maik Yohansen, Yurii Tiutiunnyk, and Hryhorii Epik suffered political persecution. F. Lopatynsky's last film, Karmeliuk, was produced in 1930. In 1932 Oleksander Dovzhenko completed his first sound film, Ivan. After this he was accused of being a Ukrainian nationalist and was forced to live as though in exile in Moscow for the rest of his life. There he worked in Mosfilm. His next film, Aerograd (Air City, 1935), lacked the slightest hint of a Ukrainian theme. Shchors (1939), which was ordered by Joseph Stalin and produced during the Yezhov terror, contains only a few scenes that recall Dovzhenko's artistic power. In the 1930s Ivan Kavaleridze was quite successful in making films on Ukrainian themes: Perekop (1930), Koliïvshchyna (1933), and Prometei (Prometheus, 1935). Later he also adapted the operas Natalka Poltavka (1935) and Zaporozhets’ za Dunaiem (Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube, 1937) for film. Until the Second World War the standard film was an adaptation of a literary work about a Soviet civil war hero (eg, Yurii Yanovsky's Vershnyky [The Riders, 1939]). Ukrainian history was distorted, as in Oleksander Korniichuk's screenplay Bohdan Khmel’nyts’kyi (1941). These last two films were directed by Ihor Savchenko, one of the outstanding directors of the Ukrainian cinema of the 1930s–1940s. The decline in quality was accompanied by cutbacks in production, from 30 films in 1931 to 10 in 1933 and 7 in 1941.

1941–5. By the beginning of the Second World War the Ukrainian cinema was in a state of almost complete ruin: either short propaganda films were produced, or films begun before the war were completed; for example, Dochka moriaka (The Sailor's Daughter, 1941), directed by Heorhii Tasin; Mors’kyi iastrub (The Sea Hawk, 1941), directed by Volodymyr Braun; and Oleksander Parkhomenko (1942), directed by L. Lukov. The majority of the films made until the end of the war were adaptations of war novels: Oleksander Korniichuk's Partyzany v stepakh Ukraïny (Partisans in the Steppes of Ukraine, 1942), directed by Ihor Savchenko, and Wanda Wasilewska's Raiduha (The Rainbow, the only Ukrainian film released in 1944), directed by M. Donskoi. Oleksander Dovzhenko's two documentary films of this period should be mentioned: Bytva za nashu Radians’ku Ukraïnu (The Battle for Our Soviet Ukraine, 1943) and Peremoha na Pravoberezhnii Ukraïni (The Victory in Right-Bank Ukraine, 1945).

Postwar production, 1945–55. During Andrei Zhdanov's period and the growing campaign against nationalism, film production was low: one to two films per year, with six films in 1953 and 1954 and five in 1955. Except for the film Taras Shevchenko (1951), directed by Ihor Savchenko and starring Serhii Bondarchuk, nothing of artistic worth was produced during this period. After the war Russification efforts increased: the better Ukrainian actors were sent to Moscow, while Russian actors filled the studios in Ukraine.

1956–69. From 1956 onwards the Ukrainian cinema experienced a steady revival. This was evident first of all in the expansion of its production base: the Kyiv Artistic Film Studio and the Odesa Artistic Film Studio were expanded. In 1957 the Yalta studio again became a Ukrainian studio. Film production increased rapidly: 16 films were released in 1957 and 23 in 1958. Most of the films made in the 1950s dealt with the October Revolution of 1917; for example, Pravda (The Truth, 1957), an adaptation of Oleksander Korniichuk's novel; and Pavlo Korchagin (1956) and Narodzheni bureiu (Born of the Storm, 1957), adaptations of Nikolai Ostrovsky's novels. Some films depicted life on collective farms, for example, Daleke i blyz’ke (The Distant and Near, 1957). Screen adaptations of literary classics were also popular: Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's Pekopt’or (1956) and Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko's Svatannia na Honcharivtsi (The Marriage Engagement in Honcharivka, 1958). Some concerts and ballets were filmed, for example, the ballet adaptation of Taras Shevchenko's poem Lileia (The Lily, 1959). In 1958 the total production of artistic, documentary, popular science, and other films amounted to 109 titles. Except for a few films, such as Hryhorii Skovoroda (1959, written and directed by Ivan Kavaleridze), that were devoted to original themes, the quality of this production reflected the general level of Soviet art.

In the 1960s the quantity of production remained similar to that of the 1950s but with a falling-off tendency: 22 films in 1960, 17 artistic films in 1965, 11 in 1966, and 18 in 1967. As before, these were mainly typical screen adaptations of literary works, concerts, and operas: Mykhailo Starytsky's play Za dvoma zaitsiamy (After Two Hares, 1961), directed by Viktor Ivanov; Panas Myrny's Poviia (The Strumpet, 1961), directed by Ivan Kavaleridze; Andrii Holovko's Pylypko (1964), directed by M. Sergeev; and others. The two outstanding films of the decade were Ivanna (1960), written by V. Beliaev and directed by Viktor Ivchenko, a typical propaganda film directed against the Catholic church and nationalism; and the adaptation of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky's novel Tini zabutykh predkiv (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, 1964), directed by Serhii Paradzhanov, camera work by Yurii Illienko, and artistic direction by Heorhii Yakutovych, which won awards at film festivals in Argentina (1965), Rome (1965), and Greece (1966). Two other outstanding films directed by Yurii Illienko, Krynytsia dlia sprahlykh (Well for the Thirsty, 1965) and Vechir naperedodni Ivana Kupala (The Eve of Ivan Kupalo, 1967) were banned fom distribution by the censors. The increasing Russification of the Ukrainian cinema in the 1960s is evident from the fact that after Oleksander Dovzhenko's death all the films based on his scripts—Poema pro more (Poem about the Sea, 1958), Povist’ polum'ianykh lit (Tale of Fiery Years, 1960), Zacharovana Desna (The Enchanted Desna, 1964), and Nezabutnie (The Unforgettable, )—were made not in Ukraine but in Moscow, by his wife, Yuliia Solntseva.

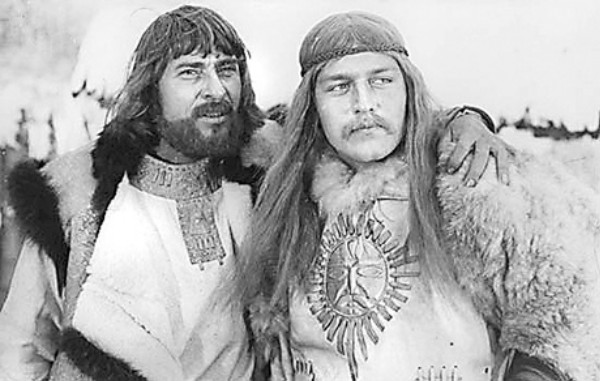

1970s. In the 1970s the Ukrainian cinema continued to develop along the basic lines fixed in the 1960s without significant variation in annual production. No films of exceptional artistic merit appeared. It is difficult to determine how many Ukrainian films were made, because the Kyiv Artistic Film Studio and the Odesa Artistic Film Studio produced Russian films as well, and these were not clearly distinguished from the Ukrainian ones. The basic themes of the films remained as before: (1) the October Revolution of 1917 and the civil war, with such examples as Rodyna Kotsiubyns’kykh (The Kotsiubynsky Family, 1970), directed by Tymofii Levchuk; a new adaptation of Nikolai Ostrovsky's Kak zakalialas’ stal’ (How the Steel Was Tempered, 1973), directed by Mykola Mashchenko; and Bilyi bashlyk (The White Hood, 1975), directed by Yurii Illienko; (2) the Second World War and the partisan movement (see Soviet partisans in Ukraine, 1941–5), with such examples as Sofiia Hrushko (1971), written by Vadym Sobko and directed by Viktor Ivchenko; Nina (1971), written by S. Smyrnov and directed by Oleksii Shvachko; Simnadtsiatyi transatlantychnyi (The Seventeenth Transatlantic, 1972), directed by Volodymyr Dovhan; a trilogy (1974–6) on Sydir Kovpak's campaign consisting of Spolokh (Alarm), Khurtovyna (The Storm), and Karpaty (The Carpathians); (3) industrial achievements, with films such as Dyvytysia v ochi (To Look into the Eyes, 1976), written by Ye. Onopriienko and directed by V. Luhovsky, and Kanal (The Canal, 1976), written by L. Cherevatenko and V. Bortko and directed by V. Bortko; (4) life on the collective farm, with such films as Tut nam zhyty (Here We Can Live, 1972), written by Mykola Ya. Zarudny and directed by A. Bukovsky, and Sered lita (In the Middle of Summer, 1975), written by Yu. Parkhomenko and Mykhailo Tkach and directed by V. Illiashenko. The antireligious struggle was continued in the film Spokuta chuzhykh hrikhiv (Penance for the Sins of Others, 1978), written by Vasyl Sychevsky and directed by V. Pidpaly. A large number of films were again adaptations of literary classics: several films based on the works of Lesia Ukrainka, and Ivan Franko's Zakhar Berkut (1971), written by Dmytro Pavlychko and directed by Leonid Osyka, Mykhailo Stelmakh's Husy, lebedi letiat’ (The Geese and Swans Are Flying, 1974, directed by O. Muratov) and Shchedryi vechir (Epiphany Eve, 1978, directed by O. Muratov), and Oles Honchar's novel Bryhantyna (The Brigantine, 1979, directed by Yurii Illienko).

In the 1970s ans 1980s some younger screenwriters have established themselves—Mykola Ya. Zarudny, Dmytro Pavlychko, and Ivan Drach. Alongside the older film directors several younger ones have appeared, among them, Yurii Illienko, noted for his films Vechir na Ivana Kupala (The Eve of Ivan Kupalo, ), Bilyi ptakh z chornoiu oznakoiu (White Bird with a Black Spot, 1972), and the adaptation of Lesia Ukrainka's Lisova pisnia (The Forest Song, 1980); Ivan Mykolaichuk, noted for his Vavylon–XX (Babylon–XX, 1979); and Ihor Hrabovsky, noted for his Lesia Ukraïnka (1971), Kryla peremohy (The Wings of Victory, 1972), and Vohnennyi shliakh (The Fiery Road, 1974). All three of these directors also wrote the scripts for some of their films.

The Kyiv Studio of Popular Science Films and the Ukrainian Studio of Documentary Films in Kyiv released several hundred titles per year, many of them of a propagandist nature. The former produced a series of historical films, including Marusia Bohuslavka, Kyrylo Kozhum’iaka, Skazannia pro Ihoriv pokhid (The Tale of Ihor's Campaign), and Lisova pisnia. A popular illustrated film magazine Novyny kinoekrana has been published on a monthly basis since 1961.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Romitsyn, A. Ukraïns’ke radians’ke kinomystetstvo (Kyiv 1958)

———. Ukraïns’ke radians’ke kinomystetstvo, 1941–1954 (Kyiv 1959)

Korniienko, I. Ukraïns’ke radians’ke kinomystetstvo, 1917–1929 (Kyiv 1959)

Zhurov, H. Z mynuloho kino na Ukraïni, 1896–1917 (Kyiv 1959)

Zhukova, A.; Zhurov, H. Ukraïns’ke radians’ke kinomystetstvo, 1930–1941 (Kyiv 1959)

Berest, B. Istoriia ukraïns’koho kina (New York 1962)

Shymon, O. Storinky z istoriï kino na Ukraïni (Kyiv 1964)

Korniienko, I. Pivstolittia ukraïns’koho radians’koho kino (Kyiv 1970)

Kriz’ kinoob'iektyv chasu: Spohady veteraniv ukraïns’koho kino (Kyiv 1970)

Leyda, J. Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film (New York 1973)

Korniienko, I. Mystetstvo kino (Kyiv 1974)

Moroz-Pohribna, L. Ukraïns’ka radians’ka kinodramaturhiia: Stanovlennia i rozvytok zhanriv (Kyiv 1976)

Shupyk, O. Stanovlennia ukraïns’koho radians’koho kinoznavstva (Kyiv 1977)

Youngblood, D. Soviet Cinema in the Silent Era, 1918–1935 (Austin, TX 1985)

Levchuk, T. et al (eds). Istoriia ukraïns’koho radians’koho kino v tr’okh tomakh (Kyiv 1986–87)

Briukhovets’ka, L. Poetychna khvylia ukraïns’koho kino (Kyiv 1989)

Hosejko L. Histoire du cinéma ukrainien: 1896–1995 (Dié 2001)

Ivan Koshelivets

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)