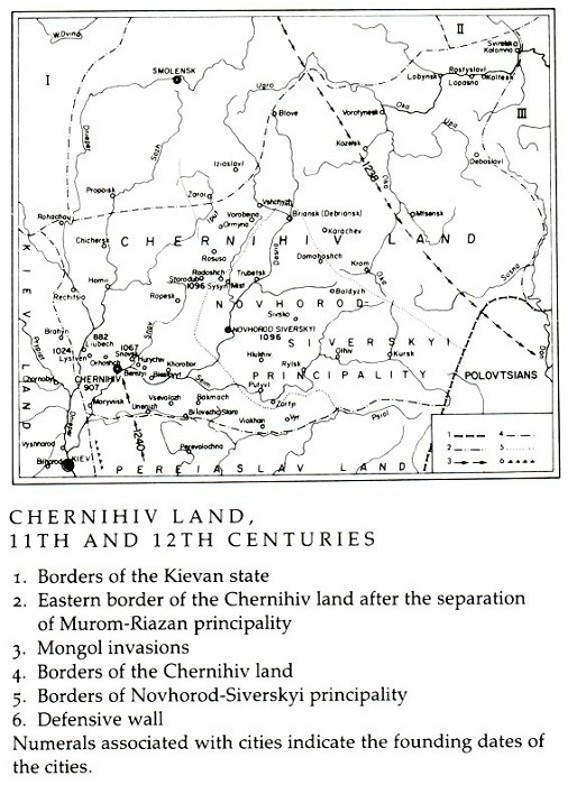

Chernihiv principality

Chernihiv principality. (Map: Chernihiv land.) One of the largest and mightiest political entities of Kyivan Rus’ in the 11th–13th century. The principality was formed in the 10th century and retained some of its distinctiveness until the 16th century. Its basic territory consisted of the basins of the Desna River and Seim River in Left-Bank Ukraine, which were settled by the Siverianians and partly by the Polianians in the south. Eventually the principality expanded to encompass the territory of the Radimichians and some of the lands settled by the Viatichians and Drehovichians. Chernihiv was the capital of the principality, which included a number of towns and cities, such as Novhorod-Siverskyi, Starodub, Briansk, Putyvl, Kursk, Liubech, Hlukhiv, Chechersk, Kozelsk, Homel, and Vyr (now Bilopillia). Until the 12th century the domain and influence of the principality expanded far into the northeast (the Murom-Riazan land) and into the southeast (Tmutorokan principality).

Until the 11th century Chernihiv principality was governed by local (tribal) elders and by vicegerents who were sent from Kyiv to collect tribute, administer justice, and organize a defense against foreign enemies, particularly the nomadic hordes. In 1024–36 the principality was ruled by Prince Mstyslav Volodymyrovych, who came from Tmutorokan. After the reign of the Kyivan grand prince Yaroslav the Wise, who unified the right-bank and left-bank territories of the Kyivan state, the principality was inherited by his son Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych, who founded the Chernihiv house of the Riurykide dynasty. The Riurykides governed the principality until the 14th century by transferring power either from father to son (dynastic inheritance) or from older to younger members of the family. Kyivan grand prince Volodymyr Monomakh ruled the principality for a time, but in accordance with the decision of the Liubech congress of princes (1097) the principality and its appanages went to Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych's sons, Oleh (Mykhailo) Sviatoslavych and Davyd Sviatoslavych, and their descendants, the Olhovych house. Although some of the appanages, particularly Novhorod-Siverskyi, developed into independent principalities (see Siversk principality), the authority of the Chernihiv prince as the head of the princely house and the supreme ruler was great enough to preserve for him the title ‘grand prince.’

The power possessed by the Chernihiv princes, the unity of the Olhovych house, and the wealth and ability of its leading members played an important role in the economic and cultural development of the principality in the 12th-mid–13th century. The policies of the Chernihiv princes were determined by the historical development of the principality and its economic and military importance and were characteristic of a great state. The Riurykides of Chernihiv always aspired to gain the great throne of Kyiv and to hand it on to their descendants. The Chernihiv house ruled Kyiv in the 11th–13th century during the reign of the grand princes Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych (1073–6); his grandsons Vsevolod Olhovych (1139–46) and Ihor Olhovych (1146–7), the sons of Oleh (Mykhailo) Sviatoslavych; Iziaslav Davydovych (1157–61); Sviatoslav III Vsevolodovych (1176–94, with interruptions); Vsevolod Sviatoslavych Chermny (1206–12, with interruptions); and Mykhailo Vsevolodovych (1238–46). At the same time these princes or their relatives retained direct control of Chernihiv principality.

With the title, authority, and influence of the grand prince of Kyiv and the resources of Chernihiv principality at their disposal, the Chernihiv princes conducted an ongoing expansionist policy. In the 11th–mid-12th century their foreign policy was focused mostly on the southeast—the Don region and Lower Volga region (the former Khazar state), Caucasia, and Tmutorokan principality. This policy determined the relations between the Chernihiv princes and the Cumans, who acted at various times either as allies of the princes in foreign undertakings and internal struggles or as opponents to their eastward expansion. One of the last attempts of the Chernihiv Riurykides at eastward expansion was Ihor Sviatoslavych's disastrous campaign of 1185, which is described in the epic Slovo o polku Ihorevi (The Tale of Ihor's Campaign). The Cuman barrier enabled the Byzantine Empire to consolidate its influence over the territory of Tmutorokan principality.

As the eastern ties of Chernihiv principality grew weaker, the attention of the princes turned westward towards the Belarusian territories of the Kyivan realm. With the consent of the Polatsk princes Chernihiv assumed the role of guardian and even sovereign over Polatsk principality. Towards the end of the 12th century the Chernihiv princes both held the Kyiv principality and enjoyed sovereignty over Polatsk principality. Thus, they were in a favorable position, after their attempts to consolidate their influence in Novgorod the Great failed, to bid for control over all Ukrainian territories, including the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, and thus for the primacy of Chernihiv principality among the principalities of Rus’. The attempt of the sons of Ihor Sviatoslavych of Novhorod-Siverskyi to gain control of Galicia ended in failure and the violent death of the brothers in 1211. In 1229 Mykhailo Vsevolodovych of Chernihiv began a prolonged struggle with his brother-in-law Danylo Romanovych of Galicia for the Kyivan and Galician thrones.

These ambitions were undermined by the Mongol-Tatar invasions. In 1223 the grand prince of Chernihiv, Mstyslav Sviatoslavych, died at the battle on the Kalka River. On 18 October 1239 Chernihiv was captured and plundered by the Tatars, and Prince Mstyslav Hlibovych died in battle. In 1245 Prince Rostyslav Mykhailovych, the Chernihiv pretender to the Galician throne, was decisively defeated at Peremyshl. In 1245 and 1246 Danylo Romanovych of Galicia suffered the humiliation of submitting to the Mongol khan's authority, while Mykhailo Vsevolodovych, who refused, suffered a martyr's death. Chernihiv principality was divided into a number of appanage principalities, which for a long time remained directly controlled by the Golden Horde.

The Grand Principality of Chernihiv ceased to exist, but Chernihiv principality, devastated and plundered by the Tatars, restricted in its rights, borders, and aspirations, survived with Briansk as the new capital. In the second half of the 13th century and at the beginning of the 14th century it was governed by princes of the Chernihiv house, beginning with Roman Mykhailovych of Briansk and Chernihiv (1263–85). Then it passed into the hands of the Riurykide princes of the House of Smolensk. In the second half of the 14th century Chernihiv principality became a vassal of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and was ruled, as were all the northern Rus’ principalities, by the Lithuanian princes of the Gediminas dynasty. During his reign as grand duke of Lithuania, Casimir IV Jagiellończyk of Poland granted Chernihiv principality to émigré princes of the Moscow Riurykides, in particular to Prince Ivan Andreevich of Mozhaisk. His son, Semen, submitted to Muscovy in 1500, and in 1515, during the rule of Semen's son, Vasyl Semenovych, Chernihiv principality was annexed by Muscovy, which in 1523 also annexed Novhorod-Siverskyi principality, the last independent Ukrainian principality.

The state traditions of Chernihiv principality outlasted its historical existence by many centuries. They were reflected in the political projects of the Cossack Hetman state of the 17th–18th century (the so-called Kunakov Articles, 1649); in Petro Petryk's Zaporozhian Cossack treaty with the Crimean Tatars in 1692, which mentions Chernihiv principality; in Hetman Ivan Mazepa's use of the title ‘Prince of Chernihiv’ in negotiations with Poland and Sweden in 1708; in the Russian tsars' use of the title ‘Grand Prince of Chernihiv,’ adopted after the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654; and finally in the history of the Ukrainian national renaissance of the 19th-20th century and the founding of a new Ukrainian state in 1917 (see Ukrainian National Republic).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bagalei, D. Istoriia Severskoi zemli do poloviny XIV st. (Kyiv 1882)

Hrushevs’kyi, M. Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy, 8 vols (Lviv 1898–1918)

Andriiashev, O. ‘Narys istoriï kolonizatsiï Sivers’koï Zemli do pochatku XVI v.,’ ZIFV, 20 (Kyiv 1928)

Kuczyński, S.M. Ziemie Czernihowsko-Siewierskie pod rządami Litwy (Warsaw 1936)

Mavrodin, V. Ocherki istorii Levoberezhnoi Ukrainy (Leningrad 1940)

Kuczyński, S.M. Studia z dziejów Europy Wschodniej X–XVII w. (Warsaw 1965)

Zaitsev, A. ‘Chernigovskoe Kniazhestvo,’ in Drevnerusskie kniazhestva X–XIII vv. (Moscow 1975)

Dimnik, M. Mikhail, Prince of Chernigov and Grand Prince of Kiev, 1224–1246 (Toronto 1981)

Dimnik, M. The Dynasty of Chernigov 1054–1146 (Toronto 1994)

Oleksander Ohloblyn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)