Chernihiv

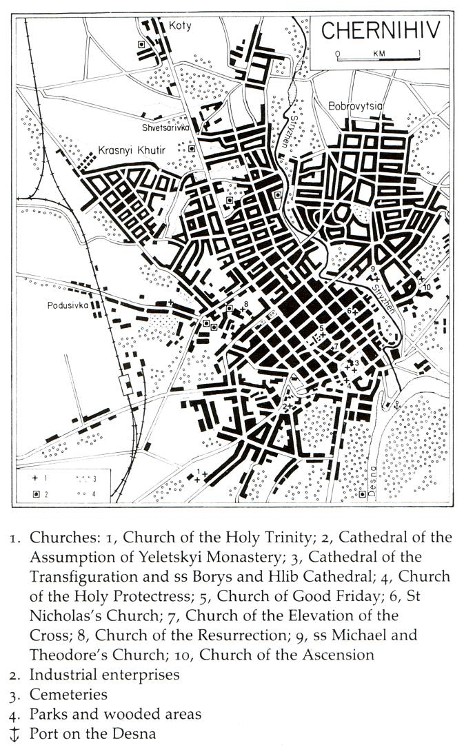

Chernihiv [Чернігів; Černihiv]. Map: II-12. City (2019 pop 288,268) in the Dnipro Lowland situated on the high right bank of the Desna River, principal city of the Chernihiv region and capital of Chernihiv oblast, railway and highway junction, with a port on the river and an airport.

History. Traces of settlements from the Neolithic Period and the Bronze Age have been found on the site of present-day Chernihiv. In historical times Chernihiv was a center of the Siverianians. The city was incorporated into Kyivan Rus’ in the 9th century and became one of the most important and wealthiest cities of the realm. According to local beliefs the kurhan Chorna Mohyla, located in Chernihiv, is the grave of Prince Chorny, the city’s legendary founder. The first mention of Chernihiv in the chronicles occurred in 907. In the 11th–13th century Chernihiv was the capital of Chernihiv principality, whose first ruler was Prince Mstyslav Volodymyrovych, the son of Volodymyr the Great. The old city was situated on an elevated terrace between the Desna River and its tributary the Stryzhen. The city center consisted of the ditynets, which was encircled by the town proper, the suburbs, and a third section known as Tretiak, which was inhabited by merchants and artisans. Each part of the city had its own protective walls. The commercial section known as the Podil stretched along the river’s edge. In the 12th century the area of the city was about 120 ha, excluding the Podil.

In 1239 the Tatars devastated Chernihiv. It fell under the control of Briansk principality in the second half of the 13th century and was incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the second half of the 14th century. In 1503 Chernihiv, along with the whole Chernihiv-Siversk land, came under Muscovy’s rule. During this period the ditynets was fortified, and the suburbs were enlarged. The city was laid waste by the Tatars several times, particularly in 1482 and 1497. In accordance with the Truce of Deulino (1618), Chernihiv was transferred to the Polish Commonwealth and in 1635 became the principal city of Chernihiv voivodeship. In 1623 Chernihiv was granted the Magdeburg law, and in 1648 it became part of the Cossack Hetman state and the capital of Chernihiv regiment.

After the abolition of the Cossack Hetman state Chernihiv became the capital of Chernihiv vicegerency (in 1781), of Little Russia gubernia (in 1797), and of Chernihiv gubernia (in 1802). At the time the city had 4,000 inhabitants. Its population increased to 12,000 by 1844, to 27,000 by 1897, and to 35,000 by 1913. During this time Chernihiv was an administrative, commercial, and manufacturing center with a small food industry; brick, candle, and soap factories; and other enterprises. The city expanded towards the west and the northwest. After the February Revolution of 1917 a Ukrainian administration was established in the city. In 1919 Chernihiv found itself in the territory contested by the Ukrainian National Republic, the Red Army, and Gen Anton Denikin, and by the end of that year Soviet authority was established in the city. It was the center of Chernihiv okruha from 1925 to 1932, when it became the capital of Chernihiv oblast. According to the 1926 census the population of the city of that time was 35,200, of whom 57 percent were Ukrainian, 20 percent Russian, and 10 percent Jewish. In the 1930s, as industry developed rapidly, the population increased to 69,000. During the German-Soviet war in 1941–4 Chernihiv suffered extensive damage.

After the war the city’s industrial capacity reached its prewar level by the beginning of the 1950s, and the population grew rapidly; it was 90,000 in 1959, of which 69 percent was Ukrainian, 20 percent Russian, 8 percent Jewish, and 1 percent Polish; 159,000 in 1970; 250,000 in 1980; and 296,000 in 1989.

Economy. The main branches of industry located in Chernihiv are chemical industry, food processing, light industry, building-materials industry, and woodworking industry. The major industrial enterprises include the Chernihiv Synthetic Fibers Plant (est 1959), the Chernihiv Woolen Fabrics Manufacturing Complex (est 1963), the Chernihiv Musical Instruments Factory (est 1934), a primary wool-processing factory, a clothing factory, a footwear factory, a meat-packing plant, a dairy, a brewery, a confectionery factory, a macaroni factory, a dry-fruits processing plant, a reinforced-concrete plant, a mechanical-repair plant, and a woodworking plant.

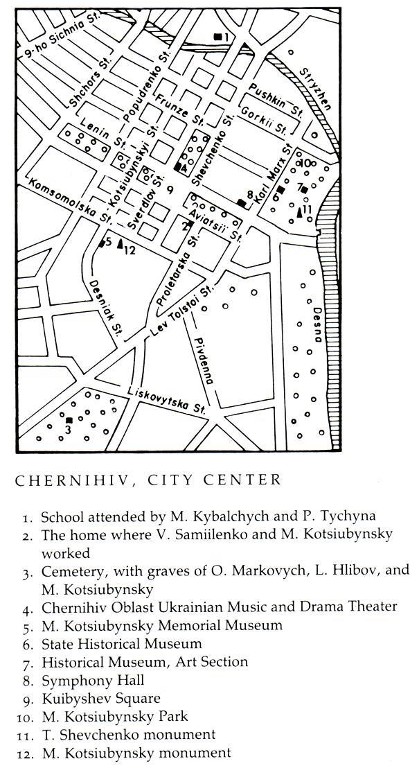

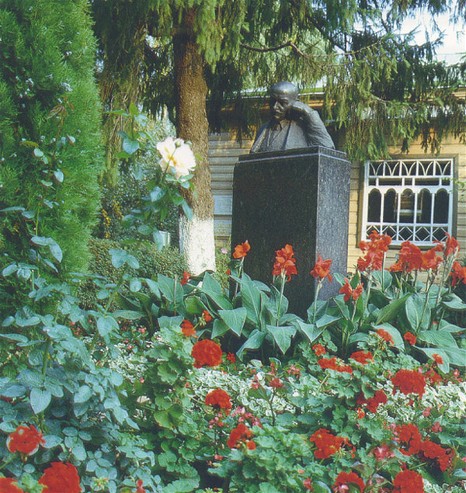

Education and culture. Chernihiv is the home of many educational, academic-research, and cultural institutions, among them Chernihiv College National University; Chernihiv Polytechnic National University; an evening mechanical-technological tekhnikum; a co-operatives tekhnikum; a commercial tekhnikum; a pedagogical and a musical school; regional branches of the Institute of Ukrainian Archeography and Source Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and the Institute of Fine Arts, Folklore, and Ethnology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine; branches of the Ukrainian Scientific Research Institute of Oil and Gas Exploration, the Ukrainian Scientific Research Institute of Machinery for the Manufacture of Synthetic Fibers, and the Ukrainian Scientific Research Institute of Agricultural Microbiology; several museums, including the Chernihiv Historical Museum and the Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky Literary Memorial Museum; a branch of the Saint Sophia Museum; the Shevchenko Ukrainian Music and Drama Theater; and the oblast philharmonic orchestra.

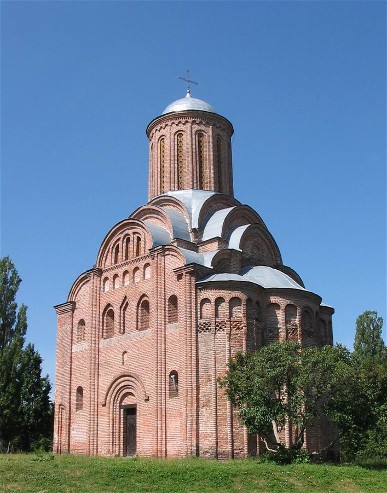

Cultural history. Chernihiv has always played a prominent role in Ukraine’s cultural life. Its cultural traditions date back to Kyivan Rus’, when the broad national scope of the Chernihiv dynasty’s political activity (see Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych, Olhovych house) secured favorable conditions for cultural development and promoted the culture of Chernihiv to an all-Ukrainian level, particularly in the areas of architecture and painting. The city’s monumental structures of the 11th–12th century, especially its churches, were remarkable achievements of the age. In the first half of the 11th century the Cathedral of the Transfiguration was erected at the center of the ditynets. The Saints Borys and Hlib Cathedral, the Dormition Cathedral of Yeletskyi Dormition Monastery, Saint Elijah’s Church, the Annunciation Church, and Saint Michael’s Church, which has not survived, were built in the 12th century. The Church of Good Friday, erected at the turn of the 13th century, was devastated in the Second World War and was later reconstructed. Chernihiv also made contributions to the development of Old Rus’ literature. Hegumen Danylo from Chernihiv wrote an account of his travels to the Holy Land at the turn of the 12th century. Although the Chernihiv Chronicle has been lost, fragments of this work have been preserved in later chronicle compilations.

The Tatar invasions and the destruction of Chernihiv in 1239 interrupted its cultural growth for many years. Chernihiv’s location on the border between the warring Lithuanian-Polish and Muscovite states did not favor its cultural renaissance. The first signs of a cultural rebirth in Chernihiv appeared only in the 17th century. The Uniate archimandrite of the Yeletskyi Dormition Monastery, Kyrylo Stavrovetsky-Tranquillon, the author of poems and theological works, set up the first printing press in Chernihiv in about 1646. The flourishing cultural life of the second half of the 17th century was connected with the work of the archbishop of Chernihiv, Lazar Baranovych, who in 1679 moved to Chernihiv the printing press he had founded in Novhorod-Siverskyi in 1675 (see Chernihiv Press). The circle of writers and artists associated with Baranovych included Ioanikii Galiatovsky, the archimandrite of the Yeletskyi Monastery; Antin Radyvylovsky, the archdeacon of the Chernihiv eparchy; L. Tobolynsky, elder of the Trinity–Saint Elijah's Monastery; the poet Ivan Velychkovsky; Ioan Maksymovych, the future archbishop of Chernihiv; the engravers Ivan Shchyrsky, Leontii Tarasevych, and Nykodym Zubrytsky; and the architects Adam Zörnikau and Johann Baptist. Owing to Baranovych’s initiative and funds provided by the Hetman administration and Chernihiv’s Cossack starshyna, the city’s architectural monuments, and particularly the Trinity Cathedral (built in the 16th century), were renovated and reconstructed in the baroque style. Of particular significance was the founding in 1700 of Chernihiv College, which became one of the main centers of learning in the Hetman state. In the first half of the 18th century the Chernihiv Chronicle and the Lyzohub Chronicle were written. Grand new churches such as the baroque Saint Catherine’s Church (1715) and secular buildings such as the regimental chancellery known as Ivan Mazepa’s building and the building of Yakiv K. Lyzohub were erected.

In the second half of the 18th century Chernihiv preserved its importance as a great cultural center. During this period the principal cultural figures were O. Shchadunsky, Dmytro Pashchenko (the author of a monograph describing Chernihiv vicegerency, 1731), the general judge H. Myloradovych, the writer Opanas Lobysevych, and the historian Mykhailo Markov. At the turn of the 19th century a circle of Ukrainian ‘patriotic nobles’ grew out of the cultural milieu of Chernihiv. Among its members were the Chernihiv gubernia marshal, Andrii Poletyka; the amateur historian Andriian Chepa; Yakiv A. Markovych; and Tymofii Kalynsky. They devoted themselves to history, collected historical documents and chronicles, and composed memoranda based on them about the history and rights of the Ukrainian gentry. These memoranda were known all over Left-Bank Ukraine. The purposes of the circle were to defend Ukraine’s right of autonomy and to obtain for the Cossack estate rights enjoyed by the nobility.

From the middle of the 19th century cultural life in Chernihiv developed rapidly. In contrast to the earlier period, in which regional and nobility interests and aspirations were dominant, general national objectives came increasingly to the fore. The following scholars and writers worked in Chernihiv during this period: the historians Oleksander Lazarevsky, Count Hryhorii Myloradovych, Oleksander Khanenko, the brothers Mykola and Mytrofan Konstantynovych, Arkadii Verzylov, and Petro Ya. Doroshenko; the ethnographers Opanas Markovych, Oleksander Shyshatsky-Illich, and Stepan Nis; the writer Leonid Hlibov; and the statisticians Oleksander Rusov, V. Varzar, Petro Chervinsky, and Oleksander Shlykevych. Some of these individuals belonged to the Chernihiv Hromada, one of the more radical hromadas in Ukraine.

Towards the end of the 19th century intellectual life in Chernihiv expanded in scope and intensity. Its main centers were the Statistical Committee; the Gubernia Archival Commission, established in 1896 through the efforts of Oleksander Lazarevsky and Hryhorii Myloradovych; and the Museum of Ukrainian Antiquities in Chernihiv, founded by Vasyl V. Tarnovsky. Scholars, pedagogues, writers, and artists of the Chernihiv zemstvo, whose work and interests often extended beyond the boundaries of the Chernihiv region, were active in these institutions.

At the turn of the century the writers Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Borys Hrinchenko, Volodymyr Samiilenko, Mykola Vorony, and Mykola Cherniavsky, the painter Ivan Rashevsky, and the historian Vadym Modzalevsky lived in Chernihiv. Young Ukrainians, most of them graduates of the Chernihiv gymnasium or seminary, gathered at the homes of these prominent artists or scholars. Some of these young people made important contributions to Ukraine’s cultural and scholarly life after the Revolution of 1917. The writers Pavlo Tychyna, Ivan Kocherha, and Vasyl Blakytny, the historians P. Savytsky, Yevhen Onatsky, Mykola Petrovsky, Vasyl Dubrovsky, and Valentyn Shuhaievsky, and the art scholar O. Hutsalo spent at least some years of their youth in Chernihiv. In 1911 the 14th Archeological Conference took place in Chernihiv. The city maintained its importance as a cultural center in the 1920s and the early 1930s. It was the home of such institutions as the Chernihiv Historical Museum (the greatly expanded former Vasyl V. Tarnovsky’s Museum of Ukrainian Antiquities), a historical archives, a learned society, and an institute of people’s education. The work of these institutions was closely connected with the work of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and particularly with the work of its historical section of the academy; the Archeological Committee; the central historical archives of Ukraine in Kyiv and Kharkiv; and the Scientific Research Institute of the History of Ukrainian Culture in Kharkiv. Their further development was curtailed by Soviet political repression in the 1930s and by the Second World War.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ocherk istorii goroda Chernigova 907–1907 gg. (Chernihiv 1908)

Hrushevs'kyi, M. (ed). Chernihiv i Pivnichne Livoberezhzhia (Kyiv 1928)

Rybakov, B. Drevnosti Chernigova (Moscow 1949)

Ignatkin, I. Chernigov (Kyiv 1955)

Iedomakha, I. Chernihiv (Kyiv 1958)

Logvin, G. Chernigov, Novgorod-Severskii, Glukhov, Putivl' (Moscow 1965)

Asieiev, Iu. Arkhitektura Kyïvs'koï Rusi (Kyiv 1969)

Karnabida, A. Chernihiv. Istorychno-arkhitekturnyi narys (Kyiv 1969)

Derykolenko, O. (ed). Istoriia mist i sil Ukraïns'koï RSR. Chernihivs'ka oblast' (Kyiv 1972)

Asieiev, Iu. Dzherela. Mystetstvo Kyïvs'koï Rusi (Kyiv 1980)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Oleksander Ohloblyn

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)