Ornament

Ornament. A decorative design, which is usually symmetrical and rhythmical. It is based on a developed semantic system derived from the repetition of symbols or signs with or without a compositional center.

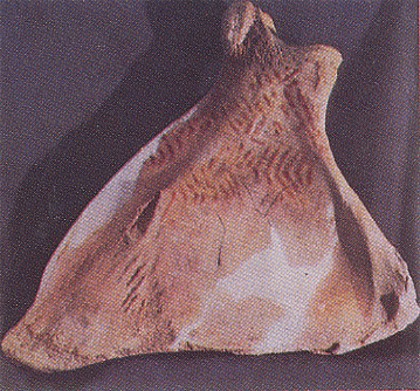

In Ukraine the oldest examples of ornament are found on Paleolithic bracelets and other artifacts made of mammoth bones discovered at the Mizyn archeological site in the Chernihiv region. Extant Neolithic artifacts reveal a greater variety of geometric ornament. The use of parallel and intersecting lines, spirals, waves, triangles, and comb shapes was characteristic of the Linear Pottery culture, the Boh-Dnister culture, the Dnipro-Donets culture, and the Sursk-Dnipro culture. The creation of the last remaining principal elements of geometric ornament was attained in the Eneolithic Period, particularly by inhabitants of the Trypillia culture, who used zoomorphic and anthropomorphic motifs. Ancient ritual ornament was based on a series of geometric archetypes and generalized, stylized, or fragmentary depictions of flora and fauna. Generally they expressed the conceptualization of cosmic phenomena and concretized ritual semantic signs.

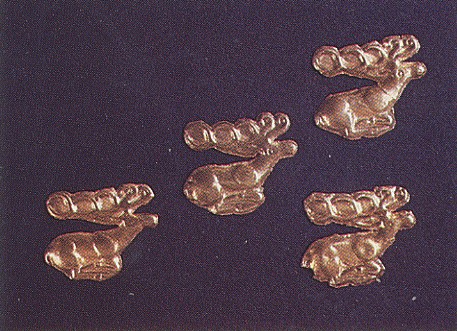

Isomorphic motifs became widespread during the Bronze age and Iron age in the ornament of the Scythians and Sarmatians and the Hellenic ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. The Greek artisans of the coastal colonies ornamented their creations in the style of their own metropolis but adapted them to indigenous tastes, and Scythian craftsmen borrowed Greek motifs in addition to making objects that were typical of their culture.

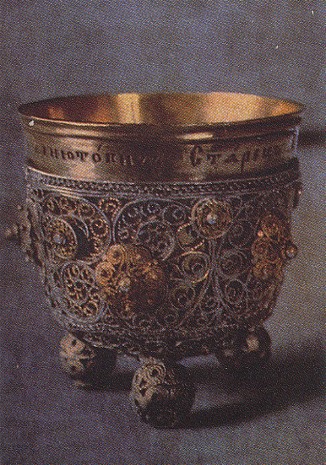

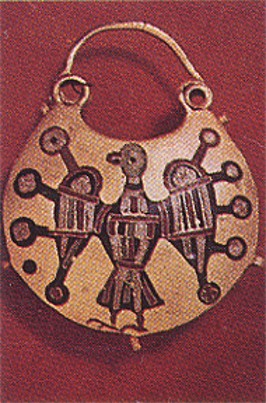

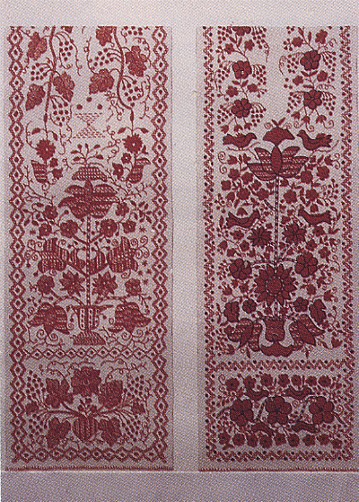

In Kyivan Rus’ the manuscripts, architecture, and implements produced for the higher classes were ornamented with Byzantine motifs and sophisticated drawings depicting mythical beasts (eg, griffins, centaurs, sirens, mermaids) and monograms of Jesus Christ. Ukrainian artisans of the late Middle Ages and early modern times often used motifs borrowed from the widespread European Gothic style, Renaissance, baroque, and classicist styles. The kilims and church vestments manufactured in 17th- and 18th-century Stanyslaviv, Korets, and Buchach were at times ornamented with Oriental (especially Persian) floral motifs. Peasant artisans also creatively adapted European styles. Renaissance floral patterns in backgrounds and borders in particular became popular. The influence of baroque ornament can be seen in the Petrykivka murals, the luxuriant embroidery of the Poltava region, and the lush floral motifs on the Easter eggs of the Chernihiv region. Heraldic eagles and Empire vase shapes were among the most popular motifs used in the woven textiles and embroidery of Left-Bank Ukraine.

Until the end of the 19th century Ukrainian peasant ornament preserved ancient geometric motifs reflecting pre-Christian beliefs and their abstract-associative and logico-symbolic polysemantic imagery. A rhomboid, for example, could symbolize the sun, or a goddess, fertility, ripe grain, a sowed field, or marriage; rhomboid rows on opposite ends of an embroidered towel, the rising and setting sun; and a rosette of eight rhomboids, virginity.

Ukrainian folk ornament has traditionally been associated with sacral and ritual objects. Like other components of the national folkloric universe (fairy tales, legends, carols, ritual folk songs, historical songs, folk painting), it has served as an expression of the ontological origins of human life, the earth, and the universe and has retained vestiges of the belief in its protective functions.

The folkways and spiritual life of the Ukrainian peasantry, which were organically tied to natural cycles (seasons) and rites of passage (marriage, birth, death), were reflected not only in ornament in general but also in its technique and the materials used. Folk ornament has had regional and local traits, which have been manifested through the use of varied motifs, rhythms, and colors. Carpathian (particularly Hutsul) textiles, Easter eggs, and works in metal and wood, for example, have been characterized by their complex geometric, polychromatic designs and multiple local variants (see Hutsuls). Textiles and embroidery from Polisia have been characterized by their age-old use of red and white. In the Middle Dnipro Basin blue was used in embroidery until the late 19th century, when, because of the noticeable deterioration in the quality of blue dyes, it was replaced by black. Embroidery in the Poltava region has been characterized by white geometric ornament on white or gray in shirts and the use of soft, muted colors. From the Dnipro River to Podilia the contrasts in polychromatic embroidery, textiles, Easter eggs, and porcelain have been progressively more pronounced. Yellows and, less often, green highlights appear in addition to the usual red-black harmonies. The range of colors is supplemented with browns and blues in Galicia and becomes most varied in Bukovyna. In the ornament of Bessarabia, Southern Ukraine and Slobidska Ukraine, which were settled relatively late and not only by Ukrainians, a complex interaction of various ethnic influences can be observed.

In Ukrainian ornament there are forms that have been particular to a specific locality and others that have been more common and even universal, in both form and name. The most widespread are spiral ‘ram's horns,’ ‘periwinkle’ leaves, infinity circles, square ‘windows,’ crosses, crosslike ‘windmills,’ rhomboidal ‘wafers’ and ‘loaves,’ various ‘branches’ and ‘combs’ with parallel teeth, ‘roses,’ ‘oak leaves,’ zigzagging ‘snakes,’ ‘grape clusters,’ ‘laurels,’ centrifugal ‘spiders,’ eight-faceted ‘stars,’ ‘teeth,’ and ‘wedges.’

The basic universal cosmological image in Ukrainian folk ornament has been the pre-Christian ‘Tree of Life’ or ‘Tree of the World’ found in ancient legends and medieval apocrypha. It includes solar signs and symbols of natural phenomena, animals, and birds that appear on Easter eggs, wagons, sleighs, embroidered towels, and pottery as ideograms of the creation and ordering of the world. These ideograms convey the spatial and temporal simultaneity of the union of humans and nature and nature and the cosmos. As a rule they constitute a tripartite, symmetrical composition consisting of the vazon (flower pot) motif and ‘branches,’ ‘paws,’ ‘laurel,’ and ‘shamrock.’ Although their various semantic meanings have been largely forgotten, their traditional significance has been preserved as an esthetic criterion in the world of folk culture.

One of the traits of Ukrainian folk ornament has been its conceptualization of motifs, even the most geometric or abstract ones, in terms of the plant world. There have been few animal or architectural motifs, which appear mainly as associative names rather than isomorphic elements.

In the early 20th century, eclecticism in folk ornament became more pronounced. The mass distribution of printed, stylized embroidery patterns squeezed out ancient local techniques and designs. Traditional motifs in engraving, ceramics, and metalwork were continued, however. Ornament became more detailed, and its rhythms became more frequent and more uniform. The use of multiple colors and tonal dispersion increased.

The gradual turn of Ukrainian folk artisans to the urban and foreign markets gave rise to the appearance of professional instructors who taught how to cater to consumer tastes. Thenceforth ornament has evolved not as a result of internal development but under pressure from external conditions. At times this state of affairs has produced the retrostylization of new works through the copying of museum artifacts, or, conversely, examples of ‘folkloric moderne’ or ‘folkloric academism.’

In the 19th and 20th centuries the creators of folk art that has not been mass-produced introduced designs from published sources, isomorphic depictions, migrating motifs, and polychromatics in ornament. Efforts to revive ornament in the early 20th century were often accompanied by the mechanical magnification (infrequently, diminution) of the dimensions of elements and motifs. When such innovations have exhausted their variational possibilities or lost their attractiveness as novelty, interest in local classical ornament has been revived, and ancient models have been reproduced.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kosacheva, O. Ukrainskii narodnyi ornament (Kyiv 1876)

Pavluts’kyi, H. Istoriia ukraïns’koho ornamentu (Kyiv 1927)

Sichyns’kyi, V. Ukraïns’kyi istorychnyi ornament (Prague 1943)

Oleksander Naiden, Mykhailo Selivachov

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 3 (1993).]

Click Home to get to the IEU Home page; to contact the IEU editors click Contact.

To learn more about IEU click About IEU and to view the list of donors and to become an IEU supporter click Donors.

©2001 All Rights Reserved. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)