Volhynia

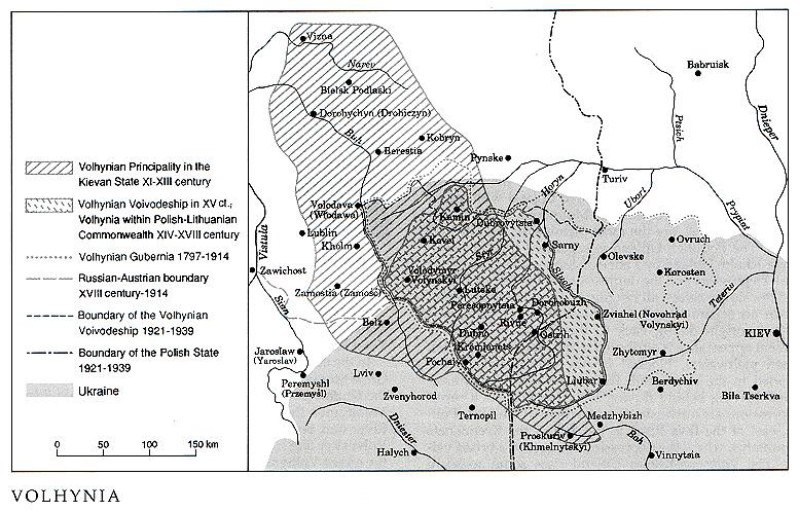

Volhynia (Ukrainian: Волинь; Volyn). (Map: Volhynia.) A historical region of northwestern Ukraine, located north of Podilia, south of Polisia, east of the Buh River, and west of the upper parts of the Teteriv River and the Uzh River (Polisia). Its area is approximately 70,000 sq km, and its population exceeds 4 million. Volhynia's borders have changed considerably over the centuries, shifting consistently from west to east. In the 12th century the Volhynia principality was larger than the present region. It extended to the Wieprz River in the west and to the Narev River and the Yaselda River in the northwest and thus encompassed the present Kholm region and Podlachia. Until 1170 it also encompassed the Belz land in the south. Under Poland the smaller Volhynia voivodeship (1569–1793) did not reach west beyond the Buh River, but included new territory to the east and southeast. Within the Russian Empire Volhynia gubernia consisted approximately of the same territory, except for the Zbarazh region, but expanded east to the upper Teteriv and the Uzh rivers. Even its capital, Zhytomyr, belonged once to Kyiv principality, not Volhynia principality. After the 1921 partition of Volhynia between Poland and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic the western part became Volhynia voivodeship. Today Volhynia encompasses most of Volhynia oblast, Rivne oblast, and Zhytomyr oblast, and parts of the former Volhynia gubernia belong to other oblasts—the Kremianets region, to Ternopil oblast, and the Iziaslav (Zaslav) and the Starokostiantyniv regions, to Khmelnytskyi oblast. Berdychiv and Radomyshl counties of the former Kyiv gubernia now belong to Zhytomyr oblast. Volhynia is usually associated with the territory of the former Volhynia gubernia, which covered 71,700 sq km and in 1914 had a population of 4,190,000. The present Volhynia oblast, Rivne oblast, and Zhytomyr oblast cover 70,200 sq km and have a total population of 3,623,000 (2001 census).

Physical geography. Volhynia is the meeting ground of two distinct landscapes: the glacial, characteristic of Polisia, and the plateau, characteristic of Podilia. From south to north the following landscape zones appear: (1) the Podolian Upland, (2) Little Polisia, (3) the Volhynia-Kholm Upland, and (4) Volhynian Polisia. East of Slavuta the zone of depressions that forms Little Polisia disappears, leaving only two zones. The northward-flowing Ikva River and Horyn River have cut deeply into the Podolian plateau and turned it into an eroded upland with mesas and pinnacles. The Kremianets Mountains, rising to 407 m above sea level, are the most picturesque part of Volhynia. The Podolian Upland is separated from the Volhynia-Kholm Upland by a zone of depressions. The upper Buh Depression and the depressions of the Styr River, the Ikva River, and the Horyn River, all ranging in elevation from 200 to 220 m, are separated by low divides. Although they are of tectonic origin dating back to the Paleozoic era, their present appearance is attributed to the Pleistocene period, when meltwaters, blocked by the continental glacier, ponded in the upper Buh Depression and spilled eastward, leaving behind fluvioglacial deposits. As a result depressions are outwash plains, particularly in Little Polisia, east of the Ikva River at the foot of the Kremianets Mountains, where the depression changes to a broad valley. The Volhynia-Kholm Upland rises some 40–80 m above the depressions. The undulating plain has an elevation of 240–300 m. It is built of chalk in the west and granite in the east and is overlain with a thick layer of loess. In the north it descends abruptly to Volhynian Polisia.

Prehistory. The earliest settlements in Volhynia date back to the Lower Paleolithic Period. Flint tools of the Acheulean culture have been uncovered in the Kremianets region. There are more finds from the Upper Paleolithic (around Kremianets, Dubno, Rivne) and even more from the Mesolithic Period (tools of the Swiderian culture and its successor, the Campignian culture). During the Neolithic Period (5500–4500 BC) and the Eneolithic Period (4500–2800 BC) Volhynia was relatively densely peopled by an agricultural tribe that developed flint tools and linear-band pottery (the Linear Pottery culture and Volhynian Neolithic culture). Then the first immigrants from the south (the Trypillia culture), from Silesia (the Volute Pottery culture), and from the northwest (the Stone-Cist Grave culture) appeared. In the Bronze Age (2800–1000 BC), the population of Volhynia quickly assimilated immigrants from Silesia (Lausitz culture), and adopted from them the cremation of the dead. It established trade with Transcarpathia, where it acquired bronze weaponry. Toward the end of the Bronze Age the culture evolved into the Vysotske culture. Its carriers, according to Herodotus, were the Nevrians. In the Sarmatian-Roman period (50 BC to 200 AD) Volhynia's contacts with the Dnister River and Dnipro River regions and the Roman trading stations on the Black Sea increased.

History. The first historical name of the people of Volhynia was Dulibians. In the 10th century that name was replaced by Buzhanians (found also in Western sources) and Volhynians.

The name Volhynia (Volyn) probably comes from a fortified town from before the 10th century, located at the confluence of the Buh River and the Huchva River. Archaeologists have discovered many artifacts from the 6th to 9th centuries, including Roman and Arab coins, at the site. The Arab geographer Mas’ūdī (10th century) called Volhynia Valinana, its inhabitants, the Dulaba, and their king, Vand Slava.

In the 9th century Volhynia came under the sway of the Great Moravian state. By the beginning of the 10th century the Dulibians were subject to Kyiv. In 981 and 993 Prince Volodymyr the Great secured the lands along the Sian River and beyond the Buh River and built Volodymyr-Volynskyi (988), which he gave to his son, Vsevolod. In the 990s a Volhynian eparchy was established (see Volodymyr-Volynskyi eparchy). From 1015 to 1030 Volhynia was the battleground of Polish-Rus’ wars. After the death of Yaroslav the Wise Volhynia was inherited by Ihor Yaroslavych and then by Iziaslav Yaroslavych, his son Yaropolk Iziaslavych (d 1087), and his grandson, Yaroslav Sviatopolkovych (d 1123). During that period Volhynia acquired political individuality. In the 1120s it passed into the hands of the Volodymyr Monomakh dynasty, and in 1154, to the Iziaslav dynasty (Mstyslav Iziaslavych and Yaroslav Iziaslavych).

Having subordinated the Galician boyars and beaten foreign invaders Roman Mstyslavych established a large state encompassing Volhynia, Galicia, and Kyiv and known as the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. After protracted wars with Hungary and Poland his son Danylo Romanovych reclaimed all of Volhynia (1227) and Galicia (1230s) and granted western Volhynia to his brother, Vasylko Romanovych. Galicia-Volhynia survived the Mongol invasion (1240–1). After Danylo Romanovych's death (1264) eastern Volhynia was ruled by his son, Mstyslav Danylovych, and after Vasylko Romanovych's death western Volhynia was inherited by his son, Volodymyr Vasylkovych (d 1288). After Volodymyr Vasylkovych's death Mstyslav Danylovych briefly brought most of Volhynia under his rule. In the second half of the 13th century Mazovia principality became subject to Volhynia.

At the beginning of the 14th century Volhynia and Galicia were reunited under Yurii Lvovych and maintained under the rule of his grandson, Yurii II Boleslav. In 1349, however, the state was partitioned, and Volhynia fell under the control of Liubartas. By the beginning of the 15th century Volhynia was a distinct principality within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Its local princes supported Švitrigaila in his bid to gain the Lithuanian throne. From 1452 to 1569 Volhynia was a province of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania consisting of Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Lutsk, and Kremianets starostvos. It came under increasing Polish administrative and economic influence, but maintained the church traditions, customs, and way of life of the Princely era. In the 15th and 16th centuries the princely and noble families (most notably, the Ostrozky princes), who led a continuing struggle against the Tatars, consolidated their privileged positions in society. As the Turks and Tatars blocked access to the Mediterranean markets, Volhynia strengthened its trade with the Baltic ports. In the 16th century the flow of Polish nobles and tradesmen into Volhynia, which was one of the most densely populated Ukrainian regions, increased. As Polish influence grew, the condition of the Volhynian peasantry became more difficult.

After the Union of Lublin (1569) Volhynia became a Polish crown voivodeship without losing its internal autonomy and Ukrainian character. The union, however, accelerated the Polonization of the administration and the upper estates of Volhynia. The struggle against Roman Catholicism and the Ukrainian national-cultural movement at the beginning of the 17th century was expressed in the writings of the opponents and the supporters of the Church Union of Berestia (1596) (see Polemical literature), the Orthodox opposition to the Reformation in Hoshcha, Lutsk, and elsewhere, the activities of the Orthodox brotherhoods in Ostroh, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, and Lutsk (see Lutsk Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Cross), and the founding of the Ostroh Academy, schools in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Lutsk, Dubno, and elsewhere, and printing presses in Ostroh (Ostroh Press), Pochaiv (Pochaiv Monastery Press), Derman, Kremianets, Kostiantyniv, and Chetvertnia.

The insurrections of Kryshtof Kosynsky (1591–3) and Severyn Nalyvaiko (1595) received wide support in Volhynia. During Bohdan Khmelnytsky's uprising rebel groups led by Maksym Kryvonis, I. Donets, and M. Tyt were active there. Some of the battles of the Cossack-Polish War of 1648–57 took place in Volhynia (Zbarazh, Vyshnevets, Brody, and, most notably, the Battle of Berestechko). Nevertheless Volhynia never became part of the Hetman state but remained a province of Poland. After Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death heavy Polish oppression and Tatar raids forced much of the Ukrainian population to emigrate to Left-Bank Ukraine. The Ukrainian nobility in Volhynia lost its political significance. As the Uniate church spread, the Polish authorities granted the Uniate Lutsk eparchy jurisdiction over the remaining Orthodox clergy. In the 18th century the haidamaka uprisings (1734, 1768) received popular support in Volhynia.

After the partitions of Poland (1772, 1793, and 1795) Volhynia, with the exception of the southern part of Kremianets county, which was taken by Austria in 1772, became part of the Russian Empire. At the beginning of the 19th century Volhynia gubernia, with Zhytomyr as its capital, was set up. But the region continued to be dominated by the Polish nobility, and the position of the Ukrainian peasantry remained unchanged. The Polish language prevailed. The school superintendent, Tadeusz Czacki, opened many Polish schools, and the Kremianets Lyceum (1819–31) served as a Polish educational center.

The Polish Insurrection of 1830–1 provoked the Russian government to introduce an anti-Polish Russification policy, particularly in Volhynia, which was part of Kyiv general gubernia. The Kremianets Lyceum, Polish schools, and many Roman Catholic and Uniate monasteries were closed down. In 1838 the Uniate Church in Volhynia was abolished. The Lithuanian Statute was replaced by Russian law, and Russian became the language of the courts and government. The emancipation of the serfs (1861) and the Polish Insurrection of 1863–4 weakened the Polish nobility. In the 1860s a program of rapid and comprehensive Russification was launched. Russian official circles set up a center for Black Hundreds propaganda at the Pochaiv Monastery. Volhynia was cut off from the Ukrainian national revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until 1911 it did not even have zemstvos, which in other gubernias provided a measure of self-government and within permitted limits supported Ukrainian cultural expression.

The process of national rebirth began in Volhynia only with the Revolution of 1917. Andrii Viazlov, a native of Volhynia, was appointed gubernia commissioner by the Central Rada. Networks of Ukrainian schools, Prosvita reading rooms, and co-operatives were organized. With the Bolshevik advance against Ukraine, in February 1918 Volhynia became the battleground of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic and the Seventh Russian Red Army. Zhytomyr served as a temporary seat of the Central Rada. In the spring of 1919 Rivne became a temporary capital of the UNR, whose army fought the Bolsheviks in eastern Volhynia, then the Poles in western Volhynia, and again the Bolsheviks in 1920. In November 1921 the Volhynian military group under Gen Yurii Tiutiunnyk staged a raid which inspired many popular revolts against the Bolsheviks (see Winter campaigns).

In 1921 Volhynia was partitioned according to the Peace Treaty of Riga: the eastern part was annexed by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the western part by Poland. Eastern Volhynia experienced the same changes as the rest of Soviet Ukraine. In the early 1920s much of the evacuated population returned to Volhynia. The Volhynian intelligentsia was active in the Ukrainization movement of the 1920s, but became a victim of Stalinist terror in the 1930s. Collectivization and industrialization changed the economic and social profile of Volhynia.

The position of Western Volhynia was unique. In the 1920s the national rebirth was promoted by a sizable group of Ukrainian intelligentsia, who had close contact with activists in the Kholm region, Podlachia, and Galicia. There was a united and fairly strong Ukrainian representation from Volhynia in the Polish Sejm and Senate (see Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation). Volhynian and Galician political groups worked closely together. Ukrainian co-operatives in the two voivodeships were linked organizationally, and their Prosvita societies co-operated with one another in spite of official prohibition and the establishment of the Sokal border. Nevertheless the authorities managed to fragment and then influence the Ukrainian political movement in Volhynia. The Volhynian Ukrainian Alliance advocated loyalty and collaborated with the Polish regime. The Polish government's Pacification and policy of terror in the 1930 elections weakened the Ukrainian parties. The governor of Volhynia, Henryk Józewski, tried to isolate Volhynia from Galicia. The authorities took strong measures to suppress Ukrainian national and cultural activity: in 1928–32 they closed down the Prosvita societies in Kremianets, Ostroh, Dubno, Rivne, Kovel, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, and Lutsk (along with 134 branches). On the eve of the Second World War there were only 8 Ukrainian elementary schools in Volhynia, compared to 443 in 1922–3, 1,459 Polish schools, and 520 bilingual schools, where most subjects were taught in Polish. There were three Ukrainian private secondary schools, but not one state school. Printed matter from Galicia was not allowed into Volhynia. In 1934, Volhynian co-operatives were subordinated to Polish co-operatives. In the border zone, which covered about one-third of Volhynia, the terror against Ukrainians was intensified: political activists were imprisoned, and people were forcibly converted to Roman Catholicism or to the Uniate church. The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) reacted to the repressions by stepping up its activities, and Ukrainian deputies from Volhynia, such as Mstyslav Skrypnyk, protested strenuously in the Sejm.

In 1939 western Volhynia was occupied by the Soviet Army and annexed by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Two oblasts, Volhynia oblast and Rivne oblast, were formed out of it, and the Kremianets region was attached to Ternopil oblast. In 1941, as Soviet forces retreated, they committed mass murders in the prisons of Lutsk, Dubno, and other cities. Initially the German occupational authorities that replaced them tolerated the revival of Ukrainian civic and religious life. But as soon as the Reichskommissariat Ukraine had been set up, in the fall of 1941, the German terror intensified. The Ukrainians of Volhynia responded with armed resistance. The Germans secured the cities and railway lines, but not the countryside. They staged punitive raids on the villages, which they burned and killed their defenseless inhabitants (see Nazi war crimes in Ukraine). In the spring of 1944 the resistance was redirected against the Soviet occupational forces.

Volhynia played an important role in the recent history of the Ukrainian Orthodox church. In the early 1920s a group of Ukrainian Orthodox priests and laity in Volhynia began to Ukrainianize the Orthodox Lutsk eparchy that had been Russified until the Revolution of 1917. The Mohyla Society in Lutsk and a number of church brotherhoods were active in the work. The Kremianets Seminary and the Orthodox faculty at the University of Warsaw trained Ukrainian Orthodox priests. When the Bolsheviks dissolved the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church (UAOC) in 1930, Polish-ruled western Volhynia became its chief stronghold. After the German occupation of that part of Volhynia Bishop Polikarp Sikorsky of Lutsk became metropolitan (1942) and revitalized the UAOC. In 1943 the hierarchy of the UAOC fled to the West. Under Soviet rule the Orthodox parishes of Volhynia were forced to submit to the patriarch of Moscow.

Population. The average population density of Volhynia is 54 persons per sq km (1989 figures). The highest densities occur in the southern (80 persons/sq km) and central (65 persons/sq km) parts of Volhynia, average densities in the zone of depressions (55 persons/sq km), and the lowest densities in Polisia (40 persons/sq km). Because of lagging industrialization the proportion of the population that is urban is one of the lowest in Ukraine. In western Volhynia it was 12.1 percent in 1931 and 46.6 percent in 1987; in eastern Volhynia it was 20.5 percent in 1939 and 51.2 percent in 1987. In all of Volhynia it was only 8 percent in 1897, 17 percent in 1939, and 48 percent in 1987. The largest cities in Volhynia are (2001 figures) Zhytomyr (284,000), Rivne (249,000), Lutsk (209,000), Berdychiv (88,000), Korosten (67,000), Kovel (66,000), Novovolynsk (54,000), and Novohrad-Volynskyi (formerly known as Zviahel) (56,000).

Until the mid-19th century non-Ukrainians accounted for nearly 20 percent of the population. Among them were Jews, Poles, Ukrainian-speaking Roman Catholics, and a few Russians. After the abolition of serfdom the landlords sold some of their estates and deforested lands to colonists. Some 20,000 Czechs settled in Volhynia (mostly in Dubno, Zdolbuniv, and Rivne counties), nearly 100,000 Germans (usually on newly cleared land) in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Lutsk, Zhytomyr, and Zviahel counties, and Poles mostly in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Kostopil, and Zviahel counties. The proportion of the Ukrainians in the population declined to 70 and even 65 percent. During the First World War the Russian government deported some of the German colonists. After 1920 the number of Poles in western Volhynia increased (see table 1).

The Second World War changed the national composition of Volhynia (see table 2). Most Jews not evacuated by the Soviets were killed by the Germans. At the end of the war almost all the Germans and Czechs left, and many Poles, particularly from western Volhynia, changed places with Ukrainians living in Poland. An increasing influx of Russians and Belarusians strengthened the influence of the Russian language in the region.

Economy. Volhynia is an agrarian land with low industrial development, especially in the western part. At the beginning of the 1930s some 78 percent of the population was employed in agriculture, and only 8 percent in industry. In 1987, 52 percent of the population was rural, and most of it based its livelihood on agriculture.

Most of the sown area in 1940 was devoted to grain (73 percent), including rye (29 percent), oats (15 percent), wheat (14 percent), and barley (9 percent). Feed crops occupied 11 percent, potatoes, 9 percent, and industrial crops (sugar beet, flax, hemp, hops, and tobacco), 7 percent of the cultivated land. By the 1970s grain accounted for only about 44 percent of the sown area and feed crops had increased to 32 percent, potatoes and vegetables, to 14 percent, and industrial crops, to 10 percent. Grain yields rose from about 12 centners per ha in 1940 to over 20 centners per ha in the 1970s. Southern Volhynia produced a grain and hop surplus. In northern Volhynia forestry and animal husbandry (dairying and hog farming) prevailed.

Industrial development in Volhynia has been hampered by lack of energy resources, by competition from the more developed central regions of the Russian Empire, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and Poland, and by the region's exposed position between two unfriendly powers. After the Second World War the political and economic conditions for industrialization along the western Soviet frontier improved. The development of the Lviv-Volhynia Coal Basin has strengthened the local base for power generation. The Rivne and Khmelnytskyi nuclear power stations have made Volhynia a power exporter. Pipelines feed the major cities of Volhynia with natural gas for industrial as well as domestic use. The oil pipeline crossing Volhynia transported only Soviet crude oil to the West and contributed nothing to Volhynia's economy.

The most important industry in Volhynia is the food industry. Based on local raw materials, it accounts for over one-third of the value of industrial goods. Its major branches are grist milling, sugar refining, liquor distilling, brewing, fruit and vegetable canning, meat packing, milk processing, and butter making. Sugar refining has expanded to western Volhynia. Berdychiv has the only malt kiln in Ukraine. Other food-processing operations are more or less ubiquitous. Second in importance are the lumber industry, the woodworking industry, the furniture industry, the wood-chemical industry, the pulp industry and the paper industry. The large woodworking plants and furniture factories in Kovel, Lutsk, Rivne, Sarny, Zhytomyr, Korosten, and Malyn (Zhytomyr oblast) are based on the forest resources of Volhynian Polisia. The Kostopil prefabricated-house-building plant is the largest of its kind in Ukraine. Paper mills at Korostyshiv, Malyn, Myropil, and Chyzhivka account for 20 percent of the forest-based industrial output of the region. Third in importance, light industry accounts for less than one-quarter of the region's industrial output. The machine building industry and the metalworking industry have developed only in the last five decades. They produce equipment for the chemical industry and the food-processing industry (Berdychiv, Korosten), metal-cutting machines (Zhytomyr, Berdychiv), road-building (Korosten) and farm machinery (Novohrad-Volynskyi, Kovel, Rivne), tools (Zhytomyr, Lutsk, Rivne), automobiles (Lutsk), and railway equipment (Kovel). Volhynia's chemical industry produces fertilizers (Rivne), synthetic fibers (Zhytomyr), pharmaceuticals (Zhytomyr) and plastics (Lutsk). The building-materials industry is well developed and supplies other regions. Crushed stone and asbestos-cement (Zdolbuniv) are used for prefabricated cement products. Granite, labradorite, basalt, and other rock quarrying provides fine building stone. Local kaolin clays and sand are used for manufacturing pottery, china, and glass, particularly in a cluster of small towns between Zhytomyr and Rivne. The mining of bog iron ores is obsolete, but the discovery and development of ilmenites has given rise to nonferrous metallurgy at Irshansk, which produces titanium dioxide and phosphate fertilizers. The most important industrial centers in Volhynia are Zhytomyr, Rivne, Lutsk, Novohrad-Volynskyi, Kovel, and Zdolbuniv.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Antonovich, V. ‘Arkheologicheskaia karta Volynskoi gubernii,’ Trudy 11 arkheologicheskogo s"ezda (Moscow 1901)

Trudy Obshchestva issledovatelei Volyni, 1–13 (Zhytomyr 1902–15)

Rocznik Wołyński, 1–8 (Rivne 1930–9)

Richyns’kyi, A. Staryi horod Volyn’ (1938)

Levkovych, I. Narys istoriï Volyns’koï zemli (Winnipeg 1953)

Litopys Volyni, 1–15 (New York–Winnipeg 1953–88)

Baranovich, A. Magnatskoe khoziaistvo na iuge Volyni v XVIII v. (Moscow 1955)

Starodavnie naselennia Prykarpattia i Volyni: Doba pervisnoobshchynnoho ladu (Kyiv 1974)

Tsynkalovs’kyi, O. Stara Volyn’ i Volyns’ke Polissia, 2 vols (Winnipeg 1984, 1986)

Iakovenko, N.; Kravchenko, V. (comps); Kotliar, M. et al (eds). Torhivlia na Ukraïni, XIV–seredyna XVII stolittia: Volyn’ in Naddnipriashchyna (Kyiv 1990)

Boiko, M. Bibliohrafiia volynoznavstva v Pivnichnii Ameritsi, 1949-1993 (Bloomington, Indiana 1993)

Iakovenko, N. Ukraïns’ka shliakhta z kintsia XIV do seredyny XVII st.: Volyn’ i Tsentral’na Ukraïna (Kyiv 1993)

Petro Hrytsak, Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Yaroslav Pasternak, Ihor Stebelsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993).]

%20in%20Piddubtsi.jpg)