Sudak

Sudak [Судак]. See Google Map; see EU map: IX-15. A city (2014 pop 15,532; 2021 pop 17,834) on the Crimean southern shore and a raion center in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. It also served as a raion center, then after 1991 as the administrative center of Sudak Municipality (aka Greater Sudak, formerly Sudak raion, 539 sq km, 2014 pop 30,857, of which urban pop 16,649 and rural pop 14,208, containing the town of Novyi Svit [pop 1,117] and 14 villages).

History. A fort called Sugdaia (in Greek Σουγδαία) was built on this location in 212, probably by in-migrant Alans, for in their Iranian language, sugda means ‘pure’ or ‘holy.’ Soon afterward the fort was annexed by the Bosporan Kingdom. Roman legions advancing from Chersonesus took it and built (in 330s) two towers (‘burgs’, one of which was called ‘Suggestu’) to protect its port. In the 450s the town was destroyed by invading Huns led by Ernak. In the mid-6th century, Byzantium helped restore Sugdaia; by mid-7th century it became a seat of an Orthodox eparchy. Although the Roman towers were destroyed by the earthquake in 741, under Khazar rule (660s–1010s) Sugdaia became an important seaport. In the 8th and 9th centuries, while maintaining economic ties with Byzantium, the fort was raided by the Rus’ (probably Varangians, with one attack led by a man named Bravlin). The demise of the Khazar rule (1016) revived Sugdaia’s allegiance to Byzantium within the Chersonese Taurica thema. The fort was yielded to the Cumans (1090s–1204), then became part of the Trapezund empire (one of the successor states of the Byzantine Empire). From the second half of the 12th century the city hosted merchants from Venice (including Marco Polo’s uncle), who traded here with the Cumans and merchants from Central Asia and Kyivan Rus’. In the Rus’ documents the fort was called Surozh; it maintained commercial and cultural ties with various Rus’ principalities, notably the Chernihiv principality, Tmutorokan principality, and Volodymyr principality.

Sugdaia was besieged and taken by the Seljuk Turks led by Husam al-Din Choban in 1226, who had the first mosque built there. The Mongols raided it in 1223 and 1238; by 1249 the city came under the control of the Golden Horde. Retaining its autonomy, it prospered from trade on the Silk Road and grew to a population of 8,300, including Greeks, Alans, Mongol-Tatars, Armenians, Venetians, and Jews. Meanwhile, the Genoese merchants secured a concession from the Golden Horde for Caffa (now Teodosiia, in 1266), made it their center of operations, competed for their presence in other ports, and in 1365 seized Sugdaia, subordinated it to Caffa and called it Soldaia. On the hill east of Soldaia, enclosing part of the city and overlooking the sea, the Genoese built a sprawling fortress with 16 turrets, which today is the best preserved medieval fortress in the Crimea. Even with this fotress, howerver, Soldaia did not measure up to the Genoese port city of Caffa.

In 1475, after a long siege, Soldaia was captured by the Ottomans (with the help of Crimean Tatars), annexed and renamed Sudak; it lost its commercial importance but retained its strategic position. Some Christians left the city; others converted to Muslim faith. In 1656, Sudak was temporarily taken by the Ukrainian Cossacks. During the subsequent Russo-Turkish wars, it was occupied by the Russian army (commanded by Petr Rumiantsev) in 1771; became part of independent Crimean Khanate in 1774; and was annexed to the Russian Empire in 1783 (when the Saint Cyril’s Regiment was stationed in the Genoese fortress, and took material from its structures to build their own barracks). Wartime instability, combined with the removal of the remaining Christian residents from the town on orders of Grigorii Potemkin in 1778, reduced Sudak’s population to 33 residents by 1805.

The first Russian governor of Tavrida oblast, V. Kakhovsky, appointed (1774) the Frenchman, Joseph Bank, to settle in the Sudak Valley and manage state orchards in the Crimea. Bank commissioned the planting of Tokaj grapevines, supplied fruit from this state orchard to Saint Peterburg, and established a distillery to produce cognac and liqueurs. This development in the Sudak Valley (NE of the Genoese fortress, on the west bank of the Karahach above its confluence with the Usuuk-Su) gave rise to ‘Russian Sudak.’ The settlement gained the first Russian school of viticulture (established by Peter Pallas, functioned in 1804–1841); then the Holy Protectress Russian Orthodox Church (built 1819–20, consecrated in 1829). By 1886 ‘Russian Sudak’ had 49 homes with 245 residents, a church, and a school.

Meanwhile, Germans (originally from Württemberg) established (in 1804) a colony in Sudak on the NW side of the Genoese fortress. The colony remained a separate entity from the ‘Russian Sudak’ and built its Lutheran Church (1887). Farther on the coast, Prince L. Golitsyn established (1878) his estate at Paradis (Crimean Tatar name, Yañı Dünya, re-named in the Soviet period Novyi Svit, 4 km WSW of Sudak) where he developed a vineyard for the production of Champagne-style wines. Administratively at this time, the Sudak area was within the Teodosiia county.

The completion of the railway to Teodosiia (1892) facilitated access from there by road or boat (60 km) to Sudak. This enabled the wealthy to begin building summer cottages in the Sudak area. Even so, the main activity was grape-growing and winemaking.

Following the First World War, the Civil War, and the establishment of the USSR, Sudak became one of 10 okruha centers in the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Republic (within the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic), thus gaining a minor administrative function. The 1926 population census identified in Sudak 1,897 residents, comprising (in percent) Russians (39.9), Crimean Tatars (22.0), Ukrainians (15.7), Germans (5.4), Armenians (5.0), Greeks (2.6) and others (9.4). Outside the town of Sudak, the Sudak okruha, with a rural population of 13,898, was predominantly Crimean Tatar (89.7), with small Russian (5.0), German (2.6) and Ukrainian (1.5) minorities. At first, the Crimean Tatars were granted prerogatives, including the printing of the raion center Communist Party weekly newspaper Brigadir in their own language (1933–41) and in Russian (after 1937). However, all religious institutions were closed. In the 1930s Sudak began to develop its resort facilities; by 1939 its population doubled to 3,246.

During the Second World War, after pre-emptive deportation of Crimean Germans and evacuation of Soviet authorities, Sudak was occupied by German and Romanian armed forces (November 1941 to April 1944); a landing (16 January 1942) by the Soviet Army in a 10 day battle resulted in a loss of nearly all their men. On 14 April 1944 the Red Army retook Sudak. On 18 May 1944, the deportation of Crimean Tatars took place, village names were changed and the territory was repopulated with Russians, Ukrainians, and others. The local weekly newspaper changed its name to Put' Illicha and appeared in Russian only (1944–62, 1980–90).

After the post-war reconstruction and the improvement of the coastal highway (P29, east to Teodosiia and southwest to Alushta) and the route north over the Crimean Mountains (P35), Sudak was developed within the Ukrainian SSR as a health resort featuring its historic Genoese fort. Its population grew rapidly: from 3,612 (1959) to 9,802 (1970), 11,281 (1979), and 15,399 (1989). At first, the former German colony of Sudak remained a separate entity, renamed Uiutnoie (in Russian, or Zatyshne in Ukrainian, meaning ‘comfortable’) in 1944 when it no longer had Germans living there; it became a resort. In the 1970s it was absorbed into the town of Sudak. Sudak was granted city status in 1982.

Following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, Sudak’s population growth slowed down (due to the city’s ageing demographics): 14,495 (2001), 15,112 (2009), 15,532 (2014). Part of the growth was related initially to the returning Crimean Tatars, and later to the recovering economy. Houses of prayer were reopened or new ones built. The raion newspaper was renamed Sudakskii vestnik (1991–2005) and in 1992 an insert was introduced in Crimean Tatar, Sudaq sesi (‘Voice of Sudak’, employing Rustem Aliev, son of Esma Alieva, former editorial employee of Brigadir); no similar accommodation was made for Ukrainian readers. Financial difficulties interrupted the newspaper’s publication; it was replaced by Sudakskie vesti (2006–), a Russian-language organ of the city council with reporting by local journalists. The Sudaq sesi continued its publication.

According to the 2001 population census, Greater Sudak had 29,448 residents, comprising by declared ethnicity (in percent) Russians (59.2), Ukrainians (17.6), Crimean Tatars (17.4), Belarusians (1.3), Tatars (1.0), Armenians (0.5), and others (3.0); the city had 14,495 residents: by ethnicity (in percent) there were more Russians (64.3) and Ukrainians (19.4), but fewer Crimean Tatars (9.8); in the city, the Ukrainians were more Russified in terms of ‘mother tongue’ (in percent): Russian (77.8), Crimean Tatar (9.7), Ukrainian (9.2).

Following the Russian invasion and annexation of the Crimea (February–March 2014), a special census of its population (14 October 2014) registered a slight decline of Ukrainians in the city. Of Sudak city’s 16,492 counted residents, by declared ethnicity (in percent) they were: Russians (63.8), Crimean Tatars (16.9) and Ukrainians (12.3), with (4.7) others and (2.3) who did not declare their ethnicity. Since 2014 the city’s population fluctuated at its current size: 16,615 (2015), 16,766 (2019), 17,834 (2021).

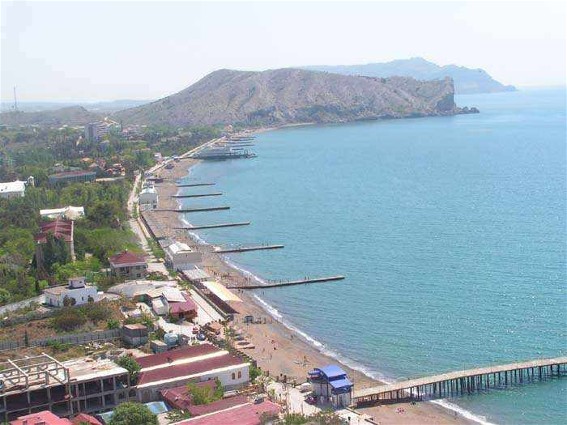

Economy. Most of Sudak’s inhabitants are employed in the city’s health resorts. Of the resort cities in the Crimean southern shore, Sudak has the sunniest conditions (2,350 hours per year) and one of the longest bathing seasons (138 days, from the beginning of June to mid-October). In all of the Crimea, only Sudak is endowed with clean quartzite sand beaches and sulfate-hydrocarbonate mineral water. Its 18 health resorts, including its largest, the ‘Sudak,’ provide treatment for non-tuberculosis ailments of breathing, heart, vascular, and nervous system. There are 60.4 ha of parkland and a ‘Water World’ for recreation, as well as scenic nature outside the city (the Kara-Dag Nature Reserve; the natural monuments Ai-Serez, Karaul-Oba, and Liagushka Peak; and the 477 ha Novyi Svit State Botanical Reserve [est 1974 for the protection of the relict species Stankevych pine, prickly juniper, and tree-form juniper]), and historic-cultural attractions (see below). Until 2014, each summer the city was visited by some 180,000 tourists; in 2003 its 18 health resorts accommodated 49,000 vacationers, one-third coming from abroad.

The city’s tourist industry is supported by 12 hotels, camping facilities, some food processing (notably flour-milling), restaurants, a travel bureau, and city (10 routes) and inter-city bus connections.

Vintage wines are produced at the Sudak Winery (in the city) and at Soniachna Dolyna (small winery making red dessert wine) and Champagne type wines at the Novyi Svit Winery (at Novyi Svit). Rose essential oils are made in Sudak.

Historical attractions. The Genoese fortress (11–14th centuries) and three Byzantine churches which survived from the 9–13th centuries are the main attractions. Others are more recent.

The Genoese fortress occupies a hill sloping to the NW with its high point at its seaside cliff; its wall and towers enclose an area of 27.9 ha. Its construction extended over 4 periods, using different building techniques, and involved renovation of existing structures. The last period (1365–1475) is known from documentation engraved on plates. The walls formed two lines of defense: the extensive walls with towers at lower elevations with a gate in the northwest encompassed some of the city of Soldaia; the upper segment protected the citadel (comprising the consul’s residence, its courtyard, and its defense tower). The observation tower was located on the highest southernmost point, above the cliff overlooking the sea. Inside the walled city are the foundations of St. Matthew Byzantine church (12–14th century), the remains of the Virgin Mary Catholic Cathedral and Russian barracks. The area also contains a well-preserved mosque (built in the 14th century, converted [1423] into a Genoese church or reception hall, reverted to a mosque in 1475; subsequently it served as an Orthodox chapel [1745–1816], became a Lutheran church [1827] and in 1883 an Armenian Catholic Church; currently it serves as the Genoese fortress museum’s exhibition hall).

Conservation of this fortress began with its acquisition (1868) by the Odesa Society of History and Antiquities; it did field research and some restoration in 1890, 1894, 1895, 1907–12 and published its findings in Zapiski Imperatorskogo Odesskogo obshchestva istorii i drevnostei. In the Soviet period the fortress became (1925) a branch of Moscow’s State Historical Museum, with significant research and restoration by specialists from Moscow and Leningrad (1926–30). In 1958 it became a branch of the Saint Sophia Museum in Kyiv (which, following the 1991 Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, was re-named the Sophia of Kyiv National Sanctuary Complex). That institution sponsored archeological and architectural research (1960s–2000s), published Sugdeiskii sbornik (from 2003), and twice applied (2007 and 2010) to have the complex listed among the UNESCO world heritage sites.

Churches from the Byzantine period are: 1) Holy Prophet Elias (in the village Soniachna Dolyna; built in 9–11th centuries on the site of an earlier church, it contains a column marble cap dated 4–5th centuries brought from Constantinople; it is the oldest functioning church in the Crimea; attended by Greeks until their resettlement in 1778, closed in 1936 and used as granary, reopened for service to Romanian troops [1941–4], then abandoned until renovations and reopening beginning in 1998); 2) Saint Paraskeva (in Latin, Paraskevi, built in 12–13th centuries, restored in 2010, NW of gate to Genoese fort and now next to the 19th century Lutheran church; on its property is the grave of Christian von Steven, founder of the Nikita Botanical Garden; 3) Twelve Apostles (built in 12–13th centuries near the port, its altar fresco depicting the Last Supper, seen in 19th century, did not survive the Soviet period, repair work done in 1987–8, frescoes recreated and church consecrated in 2009). There are also ruins of a large Byzantine church (built in 12–13th centuries, probably consecrated to Saint John Chrysostom, at the foot of Mount Kilisa-Kaia, 5 km NE of Sudak).

Other historic churches are 1) the Protection of the Mother of God Russian Orthodox Church (built 1819–29, closed by Soviet authorities in 1936, opened for service by German authorities in 1942, closed in 1962 and transferred to the Sudak school as a Pioneer Palace, returned to religious service in 1990); 2) the Lutheran Church (built in 1887, closed by Soviet authorities and converted into a clubhouse, then a movie theater, reopened in the post-Soviet Ukraine as a museum and for occasional Baptist religious services).

In addition to one in the Genoese fortress and the Lutheran Church, there is the Sudak Historical Museum in the former mansion of the German scientist, Baron J. Funk. It summarizes 4 periods: the ancient history of the region; the period from the Middle Ages to the 18th century; Sudak in the Russian Empire; and changes from the late 19th century to the present. There is also the House-Museum of Prince L. Golitsyn and his wine cellars in the Shaliapin Grotto in the town of Novyi Svit.

City Plan. Greater Sudak occupies the easternmost segment (about one-third, by area) of the Crimean southern shore. It borders in the west on Greater Alushta, in the northwest on Bilohirske raion, in the northeast on the former Kirovske raion (since the 2020 raion consolidation, on the Teodosiia raion), and in the east on Greater Teodosiia. On a map, Greater Sudak takes the form of an irregular triangle; its base is the Black Sea (about 36 km, measured in a straight line, or 70 km along the curved shore); from each end it extends inland 8–14 km to the Crimean Mountains, but at mid-point (city of Sudak) forms a narrow (1–2 km wide, 9 km long) passage over the Crimean Mountains (to 28 km from the coast). Most of the terrain in Greater Alushta is hilly (elevations 100–300 m) to mountainous (400–800 m), mostly wooded, with some river valleys and lower elevations where most of the settlements and vineyards are found.

Administratively, in 2014 Greater Sudak comprised 8 councils: the city of Sudak (23.5 sq km), the town of Novyi Svit, (0.8 sq km), and the village councils of Dachne, Hrushivka, Mizhrichchia, Morske, Soniachna Dolyna, and Vesele encompassing their 14 villages. These settlements are, with the villages grouped by councils, from the southwest to the northeast (their historic names that were replaced are in Crimean Tatar Latin script): Morske (Qapsihor), Hromivka (Şelen); Mizhrichchia (Ay Serez), Voron (Voron); Vesele (Qutlaq); the town of Novyi Svit (Yañı Dünya); the city of Sudak; Dachne (Taraq Taş), Lisne (Suvuq Suv); Hrushivka (Salı), Perevalivka (El Buzlu), Kholodivka (Osmançıq); Mindal’ne (Arqa Deresi), Bahativka (Toqluq), Soniachna Dolyna (Qoz), Pryberezhne (Kefessiya).

The city of Sudak on a map has an irregular, multi-pronged shape. Its base is the Black Sea coast (from two highlands with a small cove [the western part, 1.25 km] and along Sudak Bay [the eastern part, 2 km] to the headland of rocky Mount Alchak [157 m]); its prongs follow the valleys and roadways out of the city (SW, towards Novyi Svit, NW along Coastal Highway P29 towards Alushta, N along P35, and in the east, an industrial park and a residential quarter.

The city’s main, Lenin Street (aka Tourist Highway), is on the west side of Sudak valley. At its north end it feeds into Teodosiia Highway going east to cross both the Karahach and Suuk-Su rivers, turns north, then branching off, with the eastern branch becoming P29 (the Coastal Highway to Teodosiia) and the northern branch as highway P35 leading north over Crimean Mountains and thence via other highways to Simferopol or Kerch. To the south, Lenin Street forms the central city axis, then turns west, and then continues, as Seaside (Prymorska) Street, through Zatyshne (in Russian, Uiutnoie), to Novyi Svit.

Lenin Street hosts the city’s civic, commercial, and social establishments. Residential districts, comprising mostly of 1–2 story houses, are to the west or east of it. On the west side, they are the ‘South–West’ and, south of it, Zatyshne (Uiutnoie). To the east and beyond the mixed-use center, on the east bank of the Suuk-Su, are the Dolynnyi (Lowland), and south of it, the Achiklar residential districts The Akvapark (Aqua Park) forms the south-central residential district on the west bank of the Suuk-Su.

Going south along Lenin Street, from near the northern end, where the 19th-century ‘Russian Sudak’ emerged, are (on the east side) the Sudak market and the Intercession Russian Orthodox Church. Across the street on the west side are School No. 1, west of it, a polyclinic and a hospital, and south of this grouping, a block of multi-story apartment buildings. South of the church, on Lenin Street (E side) is the Sudak City Lyceum, the Sudak House of Culture, and a small park and (W side) School of Music; south of the park, on Gagarin Street (N side) is the Central City Library; south of Gagarin Street, on Lenin Street (W side) is the Chaika Movie Theater, the city’s communications center, and (E Side, at Pochtova Street) the Sudak City Courthouse. As Lenin Street turns SW it passes city hall (SE side), fronted since 2016 with a statue of an appropriated ‘Surozh Bishop’ (Anthony of Surozh [Andrei Borisovich Bloom, b 1914 in Lausanne, Switzerland, d 2003 in London, England, who was bishop of the diocese of Surozh, the Patriarchate of Moscow’s diocese for the United Kingdom and Ireland, not of Sudak in the Crimea]), then the Hill of Glory Park, the Sudak Sanatorium, the Sugar Head Rock Park, and the Soldaia Grand Resort.

Upon entering Zatyshne (Uiutnoie), the street name changes to Seaside (Prymorska) Street, which passes (on its S side) the Lutheran Church and behind it the Saint Paraskeva Church, then turns south, crosses the Krymska Vesna Resort and then meanders west to Novyi Svit; along the way there are access streets 1) from Zatyshne SE to the entry gate of the Genoese fortress and 2) from the south side of Krymska Vesna Resort to the old Sugdaia/Soldaia/Sudak port with two active wharfs, the Twelve Apostles Church, and the port defense towers.

Access to the sandy beaches on Sudak Bay and seaside recreational activities is provided by several streets. The westernmost, off Lenin Street, skirting the west side of Sudak Sanatorium, is the Morska Street and Ushakova Street, the latter with the Sudak Historical Museum (W side), connect to the western end of the Naberezhna Street, along the beaches on its south side. Central access is provided by the Resort Highway, which branches off Lenin Street on the east side of Sudak Sanatorium and the west side of the Hill of Glory Park, leading to the central part of Naberezhna Street; this area has some hotels, various attractions and services. East of it the route is replicated by the pedestrian Cyprus Avenue, which branches off Lenin Street at city hall and Royal Hotel and makes its way, past restaurants and wine stores, towards the mid-point of Naberezhna Street. East of it, inland from Naberezhna Street, is a military sanatorium with a theater and tennis courts and east of it, the Sudak Aqua Park (est. 2003). Access to them from Lenin Street is provided by Gagarin Street, which hosts the Central City Library and the youth sports school (N side).

Gagarin Street branches east to Communal Street; together they form the E-W arterial through Sudak. Communal Street crosses the Karahach and the Suuk-Su, on its S side passes the largest School No. 4 with its stadium and 2 football pitches, provides access to residential districts on both N (Dolynnyi) and S (Achiklar) sides, and ends at a traffic circle with the Eastern Highway. That highway defines the eastern side of Sudak with two exceptions; to the north, it serves some industrial establishments (on its E side) before connecting to P35; to the south it passes a residential neighborhood (on its E side) and then turns east before reaching Mount Alchak to coastal recreational areas beyond Sudak’s city limits and the villages of Mindalne and Bohativka along the old route to Teodosiia.

The northern prong of the city includes the Suuk-Su, a Crimean Tatar residential district on the Suuk-su River (E side of Highway P35). In the center of it is the Yany Maale Mosque. On the west side Suuk-Su is the Energy Workers’ Quarter residential and industrial district. It is bound on its S side by Teodosiia Highway. On the south side of the highway (within city limits) are vineyards.

Proceeding NW on Alushta Street (its SW side) beyond residential area is the Sudak bakery, then the Sudak Winery; on its NE side, apartments and food market; then (SW side) the Asret residential quarter and (NE side) the Valley of the Roses essential oils extraction plant, with fields of roses on both sides of the street.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Sudak’ in Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukraïny, vol 3 (Kyiv 1993)

‘Sudats’kyi raion’ in Heohrafichna entsyklopediia Ukraïny, vol 3 (Kyiv 1993)

Timirgazin, A. Sudak: Puteshestviia po istoricheskim mestam (Simferopol 2000)

Papageorgiou, Angeliki. ‘Sougdaia’ Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Black Sea (Tavros 2008)

Zharkykh, M. ‘Sudak’ in Entsyklopediia istoriï Ukraïny, vol 9 (Kyiv 2012)

Zharkykh, M. ‘Sudats'ka fortetsia’ in Entsyklopediia istoriï Ukraïny, vol 9 (Kyiv 2012)

Zharkykh, M. ‘Sudats'kyi zapovidnyk’ in Entsyklopediia istoriï Ukraïny, vol 9 (Kyiv 2012)

‘Karta Sudaka, Kryma, z vulytsiamy’ in Mapa Ukraïny https://kartaukrainy.com.ua/Sudak

Ihor Stebelsky

[This article was updated in 2024.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)