Brotherhoods

Brotherhoods (Ukrainian singular: братство, bratstvo). Fraternities affiliated with individual churches in Ukraine and Belarus that performed a number of religious and secular functions.

The origins of brotherhoods can be traced back to the medieval bratchyny, which were organized at churches in the Princely era (first mentioned in the Hypatian Chronicle, 1159). Brotherhoods as such appeared in Ukraine in the mid-15th century (the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood was first mentioned in 1463), with the rise of the burgher class. They adopted their organizational structure from Western medieval brotherhoods (confraternitates) and trade guilds. Initially the brotherhoods engaged only in religious and charitable activities. They maintained churches and sometimes assumed financial responsibility for them, ensured that church services, in particular parish feasts, were celebrated in a ceremonious way, arranged ritual dinners for their members, collected money, helped the indigent and the sick, and organized hospitals. Since these religious and charitable activities of the brotherhoods left no visible traces, some historians, such as Kost Huslysty and Yaroslav Isaievych, do not consider the early period of the brotherhoods as being part of their history.

The brotherhoods began to play a historical role in the second half of the 16th and at the beginning of the 17th century. In this period they assumed the task of defending the Orthodox faith and Ukrainian nationality by counteracting Catholic and particularly Jesuit expansionism, Polonization, and later conversion to the Uniate church. Because they consisted predominantly of burghers, the brotherhoods acquired a secular character and often found themselves in opposition to the authoritarian practices of the clergy. Hence, they endeavored to reform the Orthodox church from within by condemning the corrupt practices of the hierarchy and of individual clergymen. Their interference in clerical affairs was one of the reasons for the favorable attitude towards the Church Union of Berestia among the Orthodox bishops. The brotherhoods brought about a revival in the life of the church by promoting cultural and educational activity. They founded brotherhood schools, printing presses, and libraries. The resulting cultural-religious movement found its literary expression in polemical literature. The brotherhoods also participated in civic and political life and maintained ties with the Cossacks.

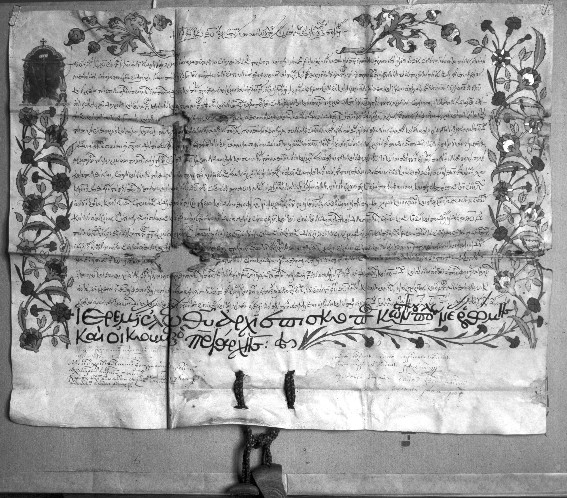

In the late 16th and early 17th century new brotherhoods were founded and existing ones were reorganized in the towns of Galicia, the Kholm region, Podlachia, Volhynia, and the Dnipro River region. Each brotherhood had its own statute (articles, regulations, procedures), modeled on the statute of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood of 1586. Membership was open to all estates, but usually only married men were admitted (unmarried men belonged to the ‘junior’ brotherhoods). At his initiation a member had to take an oath. Officers—usually four elders, including the head (a senior member)—were elected at the annual meeting.

Although brotherhood members were usually merchants and skilled tradesmen residing in the towns, some Orthodox clerics and nobles, such as Lavrentii Drevynsky and A. Puzyna, and some magnates, such as Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, Mykhailo Vyshnevetsky, Kyryk Ruzhynsky, and Adam Kysil, participated in the affairs of certain brotherhoods. The clergy and the nobility were particularly active in the Lutsk Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Cross and Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood. in 1620, Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, ‘with the entire Zaporozhian Host,’ joined the Kyiv brotherhood.

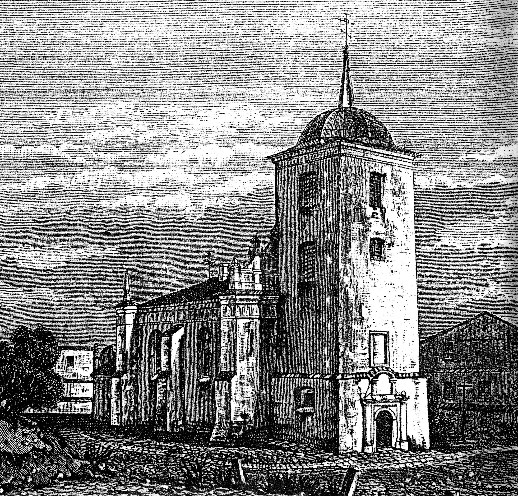

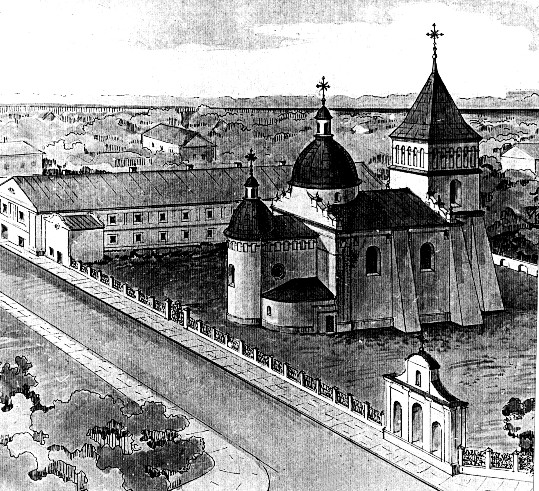

The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood was one of the oldest and most successful brotherhoods. In 1586 it received the right of stauropegion (direct subordination to a patriarch instead of a local bishop) and founded the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood School and Lviv Dormition Brotherhood Press. It maintained close contacts with Moldavian rulers and boyars. In 1588–95 there were active brotherhoods in the towns of Kamianets-Podilskyi, Rohatyn, Horodok (Lviv region), Brest, Peremyshl, Lublin, and Halych. After 1596 brotherhoods were established in Sianik, Zamość, Drohobych, Sambir, Kholm, Ostroh, Lutsk, Kremenets, Sharhorod, Nemyriv, Kyiv, and elsewhere. The Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood began to play an important cultural-educational and religious role in 1615. It founded the Kyiv Epiphany Brotherhood School that in 1632 became a college and then in 1701 the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. In 1617 the Lutsk Brotherhood of the Elevation of the Cross gained prominence.

Under the Hetman state, the Orthodox church increased in influence. The reforms of Petro Mohyla and the general improvement in clerical education enabled the Orthodox to compete with the previously superior educational system of the Jesuits, and the threat of denationalization in Ukraine diminished. Although the number of brotherhoods increased in this period, they confined their activities to the religious and charitable sphere and dropped their broader national and civic pursuits.

In Left-Bank Ukraine new brotherhoods, with a narrower focus, appeared at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century in Poltava, Novi Sanzhary, Starodub, Sribne (where the brotherhoodsupported a hospital), Lebedyn, and Kharkiv. After the Ukrainian church became subordinated to the Moscow patriarchate in 1686 and then to the Holy Synod, the Russian imperial government did not approve of the activities of the brotherhoods. Only much later, on 8 May 1864, did the Russian authorities issue a law permitting brotherhoods to be formed throughout the Russian Empire; these newly created brotherhoods, however, differed in their aims and work from the traditional Ukrainian brotherhoods.

In Right-Bank Ukraine in 1679 the Polish Sejm prohibited the brotherhoods from maintaining ties with the Eastern patriarchs; as a result, the right of stauropegion lost its significance. By the beginning of the 18th century the Uniate church had established itself firmly in Western Ukraine. The Lviv Dormition Brotherhood had accepted the union in 1709 and had received from the Pope a guarantee of its right of stauropegion. Under the Austrian regime, however, the Galician brotherhoods were dissolved by the government decree of 1788. The Lviv brotherhood was then transformed into the Stauropegion Institute.

In the 19th–20th century brotherhoods were again organized in many villages and towns, but these usually merely helped to run the local parishes. They assumed their proper religious and national tasks only during Ukraine's struggle for independence (1917–20). The Kyiv Brotherhood of the Resurrection (established in 1917 and headed by Rev Vasyl Lypkivsky) helped to convene the All-Ukrainian Orthodox Church Council, which later led to the formation of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church.

Religious life in certain internment camps for the soldiers of the Ukrainian National Republic in 1921–2 was under the care of brotherhoods. The best-known among them was the Brotherhood of the Holy Protectress (1921–4) in Aleksandrów Kujawski and then in Szczepiórno, Poland, with branches in other camps. This brotherhoodpublished Religiino-naukovyi vistnyk and books.

Ukrainian immigrants in the United States and Canada organized brotherhoods as soon as they established their own parishes. The Brotherhood of Saint Nicholas was formed in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, in 1885, and many other similar societies (such as the Brotherhood of Saint Nicholas in Winnipeg, Manitoba, established in 1905) appeared. Eventually they united into brotherhood associations, which in time evolved into mutal-aid and insurance organizations. Parallel women’s organizations, such as the Saint Olha Sisterhood in Jersey City (1897), were founded. In 1932 the Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood of Canada was established in Canada and adopted the functions of the Catholic Action societies rather than those of the traditional Ukrainian brotherhoods.

After 1945 many Orthodox and Catholic brotherhoods were created in the displaced persons camps. The statute of the Orthodox brotherhoods was adopted by the council of bishops in 1947. The most important Orthodox brotherhoods established after the Second World War were the Metropolitan Lypkivsky Brotherhood, which publishes the bimonthly Tserkva i zhyttia (Chicago); the Brotherhood of the Holy Protectress in Argentina, which published the monthly Dzvin; Saint Simon's Brotherhood in Paris; and Saint Vladimir's Brotherhood in Toronto. In the United States the parish sisterhoods together formed the United Ukrainian Orthodox Sisterhoods of the USA, which is engaged in educational and publishing activities and has published Ukraïna: Entsyklopediia dlia molodi (Ukraine: Encyclopedia for Youth, 1971).

The oldest Catholic brotherhood outside Ukraine is Saint Barbara's Brotherhood (see Saint Barbara's Church), established in the 1870s in Vienna. The church life of the Ukrainian Catholic eparchy in Australia is based on lay brotherhoods. The recent struggle for an independent patriarchate and for the autonomy of the Ukrainian Catholic church has given rise to brotherhoods and sisterhoods in the United States that continue the traditions of the old brotherhoods. The Ukrainian Catholic Lay Brotherhood of Saint Andrew in Chicago is among the better known; since 1970 it has published annually Tserkovnyi kalendar al’manakh. The Union of Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhoods and Sisterhoods of America was formed in 1976 and is based in Chicago.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kharlampovich, K. ‘Zapadno-russkie tserkovnye bratstva i ikh prosvetitel'naia deiatel'nost' v kontse XVI i nachale XVII v.,’ Khristiianskoe chtenie (Saint Petersburg 1899)

Krylovskii, A. L'vovskoe Stavropigial'noe bratstvo (Kyiv 1904)

Hrinchenko, B. Bratstva i prosvitnia sprava (Kyiv 1907)

Hrushevs’kyi, M. Kul’turno-natsional’nyi rukh na Ukraïni v XVI–XVII v. (Kyiv 1912)

Savych, A. Narysy z istoriï kul’turnykh rukhiv na Vkraïni ta Bilorusiï v XVI–XVIII v. (Kyiv 1929)

Ohiienko, Ivan. ‘Ukraïns'ki tserkovni bratstva, ïkh diial'nist' ta znachennia,’ Nasha kul’tura (Warsaw 1937)

Isaievych, Iaroslav. Bratstva ta ïkh rol’ v rozvytku ukraïns’koi kul’tury XVI–XVIII st. (Kyiv 1966)

Nazarko, I. ‘Bratstva i ïkh rolia v istoriï Ukraïns’koï Tserkvy,’ in Ukraïns’kyi myrianyn v zhytti Tserkvy, spil’noty i liudstva (Paris–Rome 1966)

Isaievych, Iaroslav. ‘Dzherela z istoriï bratstv,’ in Dzherela z istoriï ukraïns’koï kul’tury doby feodalizmu (Kyiv 1972)

Isaievych, Iaroslav. Voluntary Brotherhood: Confraternities of Laymen in Early Modern Ukraine (Edmonton–Toronto 2006)

Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]